STUFFED (39)

By:

October 20, 2019

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

In August, I drove with my family from Boston to visit my brother in Durham, NC. On the way down we stopped in Atlantic City because it was 1) cheaper than anything else around and 2) I thought some exposure to late-stage capitalism would be good for my kids.

My daughter, on seeing our somewhat beleaguered hotel room at the zombie end of the boardwalk, seemed less sure, and when we walked out into the thick evening air, saw the grey tide breaking, and the handful of remaining casinos blinking desperately at us from their huddle at the far, far end of the boardwalk, was sure to tell me that I’d done a dumb thing. Maybe — but I’d never been, and thought it was sort of grimly cool. We stayed right next to the cast-off husk of the one-time Golden Nugget (built by Michael Milken in 1980! It was also the Bally’s Grand, The Grand, Atlantic City Hilton and ACH before it was assumed into casino heaven) right on Pacific Avenue — which is a really nice property in Monopoly.

Anyway, we drove down the Jersey shore and took the car ferry across Cape May — which is reasonably priced and lovely. We saw dolphins and oil tankers and sat in adirondack chairs. The ferry takes you to where, apparently, they keep Delaware. It was nice — seemed suspiciously recently washed and a little like a movie set of what people who didn’t know what Delaware looks like might expect Delaware to look like. Even the couple of (pretty) good old boys wearing faded Megadeth t-shirts and trucker caps who jaywalked in front of us somewhere near Rehoboth Beach were conspicuously well groomed. From there we drove through the Delaware portion of Virginia and then through/over the aptly named Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel where a GPS malfunction/bridge-tunnel-induced driving coma resulted in us going in circles for a while. Looking east, it’s easy to imagine shiny infrastructure projects like this all over the country, but, of course, on the other side are the endless Navy shipyards, a depressing reminder that war is still the only easy way that tax dollars get spent on anything cool.

When we emerged, we turned inland, and looking at the map, now, I see that we passed by the Great Dismal Swamp while cutting across Virginia in search of I-85. It’s a funny drive because you are stuck in a sort of null space for so long, everything has the sameness of an airport terminal, all the way from Boston to the end of the bridge-tunnel. Compared to, for example, driving I-40 where the convenience stores are changing all the time, selling you pecan logs or hot chicken, and billboards shout about weird local enthusiasms. It’s not until you pop out and head west that a sense of place reemerges and you start to get boiled peanuts and sweet tea and gas station marts that take their chicken seriously.

Right on the North Carolina border lies Brunswick County (population ca. 16,244). It’s pretty sleepy but does have a piece of I-85 as well as a stretch of US-58 which connects I-95 to I-85 and continues to points west (including South Boston, VA, where it is extremely unlikely that you will be called upon to bang a uey in order to stop at Dunkies). We were on 58 heading towards I-85 for a short drive to Durham and I remember thinking — blithely, ironically, forebodingly — that I should stop speeding, since the risk/reward was now tilting the other way. You can make up a lot of time speeding for 10 hours, but I try to keep it sensible towards the end of trips. Anyway, naturally, I get pulled over for doing 70 (which seems high, but no doubt he was set up to catch me at the bottom of a hill or some shit) in a 55 which, I think most of you will agree, isn’t really speeding at all (to most right-thinking people, 65 means “under 80” and 55 means “under 70,” amirite?). The trooper is younger than some boots I own, calls me sir a lot, and, of course, is wearing a dumb hat, all of which is irritating. His explanation is sort of long, but I’m mostly just nodding politely and hoping (once I realize, despite what a nice yankee family we so obviously are, that he is actually going to give me a ticket) he’ll just yank the bandaid and let me out of there.

Only later did I realize, after eight (!!!) law firms sent me solicitations after my case was docketed, that it’s not a ticket at all — it’s a summons sucking me into their bullshit jurisprudence-for-profit scheme. You have to show up for court or else “pre-pay” your fine — a nice, dystopian turn of phrase, that — and if you have the temerity to pay, you will be pleading guilty and they’ll put however many points on your license they decide is most entertaining. In fairness, as much as I might want to play the persecuted yankee, the scheme is pretty obviously designed to extract maximum money from North Carolina triangle residents. Brunswick County has less than 1/10th of 1% of the population of NC’s research triangle through which I-85 conveniently passes and it’s easier to get your license suspended in NC than most places. It’s punishment for passing through: They stop you, take a little, let you go on your way a little poorer, your attitude a little worse and, if you’re me, a permanent, seething hatred of Virginia boiling ceaselessly in your belly.

Anyway, what’s past is prologue and sometimes literally: While hanging with my brother in Durham, we talked a lot about local food traditions, pulled pork (of course) but also pimento cheese, and Brunswick stew — which, he said, was popular in North Carolina but which had conflicting origin stories in Virginia and Georgia: “I bet they are all bullshit,” I said, “and maybe I can prove it’s not from Virginia and pay those fuckers back for this ticket.”

I wasn’t just talking out my ass. Almost all food origin stories are nonsense (as I’ve tried to show over the years), and tend to rely on contrived situations and unlikely accidents.

Brunswick stew is a folk recipe, a half-wild meal, so there is elasticity in the ingredients. But most basically, it is: meat, potatoes, tomato, corn, and vegetables and beans. There are, I’ve found, adherents to various belief systems based on the type of meat — squirrel, possum or other small game, some lapsed and using chicken along with pork evangelizers and beef apostates further south — potato/tomato ratios, beans (lima vs. butter), and vegetable (corn, okra, others). There are thickness venerators, potato disbelievers, corn true believers, and dogmatics that will die on each and every one of these hills, including, in true Southern fashion, whether it’s a main course or a side dish. It is slow-cooked for hours, often in giant cauldrons, until the oversized spoon stands up on its own.

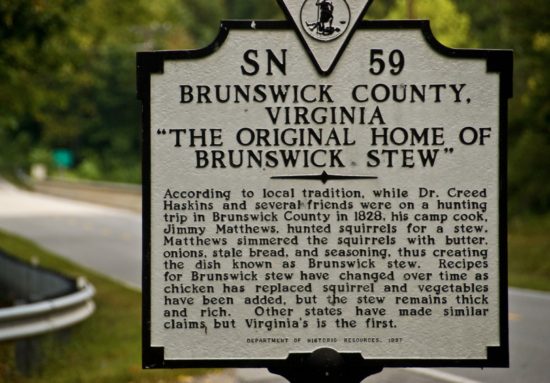

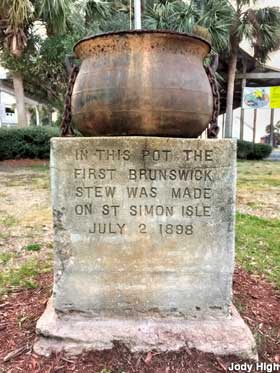

Virginia claims to have invented the stew some time in the 1820s, Georgia in 1898, while North Carolina, where there is also a Brunswick County, makes no claim to ownership. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, in Cross Creek Cookery (1942), says it was one of Queen Victoria’s favorites and came originally from Braunschweig, Germany, but no one really thinks that’s right. (Though Brunswick, Virginia was, in fact, named after the Duchy in Germany).

Like all stews it is a melange, cooked for so long that the flavors commingle and collaborate. You might well give some side-eye to a pile of butter beans on a dinner plate, but you’ll be thrilled to find them in a stew.

The earliest origins proposed are from the 1820s where James Matthews, a veteran of the war of 1812 and famed squirrel-hunting Lothario (“it was his way of cooking squirrel which gained him much popularity and éclat with the ladies” says an 1886 newspaper article on the stew’s origins) developed the beginnings of the stew which he then served, maybe, to President Andrew Jackson (naturally)… and I’m going to stop them right there. How is this a thing? He had a special way of cooking squirrel where you slow-boiled it until it fell off the bone, you strained the bones, added some spices and nothing else (no vegetables, nothing), and why is this Brunswick stew? Why not just say you invented soup? Or squirrels? Or boiling? Anyway, according to an account based on the “brunswick stew letters” discovered in 1907, this squirrel soup recipe was handed down a few generations until someone thought to add tomato, potato, butterbeans and corn in the 1830s. Most of the origin stories make a point of tomato being a new ingredient in the 1830s — apparently angling the stew as cutting-edge — but Mary Randolph’s 1824 Virginia Housewife had recipes for stewing tomatoes with lamb and for tomato catsup and tomato marmalade. So the tomato was sort of on the early side, but not groundbreaking. Over time, according to this legend, squirrel often became chicken, pork, or other meats, and other vegetables were added or subtracted as fashion and tastes dictated.

In Brunswick, Georgia, they have a giant kettle which produced, they say, the first Brunswick stew in 1898 on nearby St. Simons Island. The date puts them way behind the inventions of their northern competitor, and the pot being moved to Brunswick is pretty sketchy… but their story is not without inherent credibility. St. Simons island was home to the indigenous Creek people and, later, the Gullah Geechee people, who both made stew in the 18th century. Geechee cuisine is famous for not only gumbo, but their use of game like squirrel (the terrific 1970 cookbook/memoir Vibration Cooking by Verta Mae even has a simple squirrel soup recipe along with the varied gumbos and stews). Presumably some Georgians found out about Geechee stew on St. Simons island, then hightailed it back to Brunswick where they kept the stewpot as both evidence against Virginia’s version of events and to permanently implicate themselves in the original theft of the stew? But I’m hardly the first to wonder some of this: Way back in 1987, John Egerton, in Southern Food, offered that it was likely that Native Americans were stewing meat, corn, potatoes and local vegetables in that very spot before Virginia or Georgia were even glimmers in some colonizer’s eye — absolutely accurate, but also spoken like a man who got pulled over in Brunswick Country, Virginia. After all, corn, tomatoes and beans were at the center of the North American diet when Europeans arrived with their notions and their turkeys. Two sisters and an aunt (lacking only the third sister, squash).

These stories, true or not, bring up more complicated, ontological questions: with the continuous substitutions over time of different meats and vegetables, as well as amounts of each — when can we say a dish is invented? When does squirrel soup become Brunswick stew and can we then trace the stew back to that and claim the whole chain of events? Why not the imperfect squirrel soup that preceded that one? And so on — you could have squirrel soups all the way down, I’m sure.

It’s not a disingenuous question (well, mostly not disingenuous) either. Most recipes start this way, trial and error for a period of time until something special emerges. Here the story frames it as a process of decades, but it could just as easily be centuries. Stews like this — if it’s even a stew, many of the regional formulations seem more like a potage (stew cooked until it is similar in consistency to a porridge) a ragout (thick main course stew) or a chowder (just kidding) — where ingredients are added as available, have been well documented for some time, and have even become a part of folklore. The “Stone Soup” folk tale, where clever but hungry travelers trick one person after another into adding ingredients, a bit of meat, carrot, potato, etc etc, to their stone soup (just water and a rock) so that they can try some of the end result which the travelers have assured them is delicious, has been around for at least 300 years and includes regional variations spanning the globe and using buttons, axes, wood, and nails instead of a stone. The story was first published in America in 1808, just before Matthews and his squirrel soup appeared.

Irish stew, the national dish of sorts, is a close relative both in flexibility of ingredients and in arguments over what constitutes a proper concoction. Lamb vs. mutton, carrots or no carrots, and on it goes. Irish stew was carried across the Atlantic and adopted as the patron stew of the itinerant, most often as mulligan or hobo stew, a communal dish where individuals each give what they can in order so that everyone could eat something better — stone soup without the trickery. In fact, one of my original plans to discredit Virginia’s stew was to claim that it was called Brunswick stew because of Irish people who came down from New Brunswick in the 19th century (this part really happened) introduced Virginians to Irish style stew made with some meat and whatever you could find. Couldn’t stick the landing on that one, though, so here we are, with a short history of vernacular stew.

In addition to Irish and mulligan and hobo stew, there are food traditions the world over that involve making stew from whatever is available (as the geographical range of the stone soup story demonstrates). Vernacular recipes that would have circulated around the three Brunswicks (I’m not leaving you out, Brunswick, NC, no matter what you might say) include the Scottish dish hodge-podge or hotch-potch which was originally a stew made with vegetables, often mutton, potatoes, but, by definition made with whatever was available. The Scottish National Dictionary has it first appearing in print in 1712, but probably circulated for a long time before that.

Burgoo is a thick stew made with things on hand; it is common in the South and lower Midwest US. It used to be a sort of porridge served on ships and was also called loblolly, but, the OED tells me, a loblolly in the US is a mudhole with a deceptive crust — lovely, that. In Kentucky, burgoo holds a pride of place in the local cuisine that is similar to Brunswick stew’s in Virginia (though less desperate). Lolblolly is old, in print in 1597, burgoo in 1743. In fact the first appearance of burgoo in this sense also included a Native American food technology called ruhiggan. This was made by pounding dried meat (venison, caribou, bison, moose, polar bear — it was a widespread invention in North America) and adding fat and usually other ingredients for interest, taste and nutrition (cranberries, lichen, dried fish, etc.). This could then be rehydrated when needed into a stew — an improved version of the portable soup that European military strategists were always hunting after.

In the upper Midwest they have booyah which is similar both culturally and gastronomically — like burgoo and Brunswick stew, it is frequently made in large batches (booyah pots are huge). Haricot (or harico) is a mutton stew and first showed up in print in 1611, a gallimaulfry (16th century through late 19th) was a ragout or stew of various things on hand and was often, like hodge-podge, used metaphorically and pejoratively. Rubaboo is a stew of meat, (bear, other game) fat, corn, other vegetables, and often, dried meat and maple syrup. It was a staple of Canadian trappers and, especially, the Métis. Gumbo is a stew made of almost anything and thickened with okra. Most of these would have been swirling around Brunswick, Virginia for a century, at least, before Matthews’ squirrel soup.

I can’t prove this, but here is what I think happened: Some guys were making stew in Brunswick, it was probably their “thing” — you know how guys are with slow cooking, they get obsessed, it becomes an all day excuse to sit around drinking and avoiding actual labor. Anyway, it’s the late 19th century, these guys are sitting around making all-day stew and they start to notice a lot of other people making similar stews. Maybe they go over to a friend’s house for dinner and what’s for dinner? Stew. Stay at an inn a county over while on a business trip buying barrels for their filling-barrels-with-things business and what are they serving for dinner? Right, stew. They get nervous. They aren’t worried about who they nabbed the stew from in the first place, they are worried about their current situation. How can they keep this thing special so spending all day, or all weekend, cooking this stuff will seem like a reasonable, even laudable, thing to be doing?

Because the story they planted in the paper in 1886 is crazy. Squirrel soup in the 1820s? Europeans had been here trying to avoid starving for 200 years and native people for millennia and this struck people as a fresh idea? The first thing people must have noticed when they disembarked and walked into the forest was the squirrels running around looking basically edible. Or the second thing, anyway, after they got over their surprise that the turkeys they had gone through all the trouble of carrying across the ocean had somehow beaten them here. But, improbably, this squirrel soup thing stuck, and they added ingredients over the years until, at some point, they stopped (notionally, anyway) and called it Brunswick stew.

When do we decide a recipe is done? When the last addition has been made, the stone soup finished, the last allowed substitution ratified, and we’ve locked it. How do you come to own even a part of a stew like this? To carve your name into it? Whether this stew wandered by, perhaps on some ancestor of route 58, was there already, or a mix of the two, the Brunswickans tried to take it, to make it their own, and then freeze it in place, a fine, feral stew, petrified. But it never works with this sort of thing. Sure, haute cuisine might be perfected and then left unchanged, and bourgeois cuisine calcified until replaced by something better… but vernacular foods like stew are harder to pin down. They wander off, get chicken in them, brisket, okra, potatoes, no potatoes, take a trip down to North Carolina and get all filled up with pulled pork. They don’t care.

But, for all that, they’ll probably call it Brunswick stew forever.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.