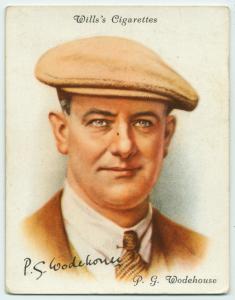

P.G. Wodehouse

By:

October 15, 2012

The comic fiction of P.G. WODEHOUSE (1881–1975) is a testament to the joy of frustration. In lesser comedies, the sympathetic characters eventually get what they want — but in Wodehouse’s architectural stories and novels, the sympathetic characters are often denied what they have badly wanted, to their ultimate delight and relief. These conclusions are often engineered by Jeeves the omniscient valet, who knows what these poor souls need better than they do themselves. Even basic communication in Wodehouse is often frustrated. What could be a more classic plot device than a telegram reading only “Come at once”? In Right Ho, Jeeves, Bertie Wooster’s deepest desire and function seems to be to frustrate not just his aunt Dahlia Travers but the very forward motion of the novel:

Before sitting down to the well-cooked, therefore, I sent this reply:

Perplexed. Explain. Bertie.

To this I received an answer during the after-luncheon sleep:

What on earth is there to be perplexed about, ass? Come at once. Travers.

Three cigarettes and a couple of turns about the room, and I had my response ready:

How do you mean come at once? Regards. Bertie.

I append the comeback:

I mean come at once, you maddening half-wit. What did you think I meant? Come at once or expect an aunt’s curse first post tomorrow. Love. Travers.

I then dispatched the following message, wishing to get everything quite clear:

When you say “Come” do you mean “Come to Brinkley Court”? And when you say “At once” do you mean “At once”? Fogged. At a loss. All the best. Bertie.

I sent this one off on my way to the Drones, where I spent a restful afternoon throwing cards into a top-hat with some of the better element.

Wodehouse himself was not nearly as lazy and comfortable as Bertie: he wrote 96 books over the course of his life, as well as poems and movie dialogue and song lyrics. He was accused of collaborating with the Nazis during World War Two, and his reputation never fully recovered, though his books tenaciously remained in print. Unlike bachelor Bertie, Wodehouse was married, and he stayed married for sixty-one years; according to his biographer Robert McCrum, this was probably an open marriage, with Ethel Wodehouse free to bring her lovers to stay while Pelham Grenville, largely asexual, sublimated any baser desires he might have had in writing. If Wodehouse’s incessant writing was indeed his way of making hay from frustration, it seems to have done the job for both him and us.

***

HUMORISTS at HILOBROW: Michael O’Donoghue | Jemaine Clement | Andy Kaufman | Danny Kaye | George Ade | Jimmy Durante | Jack Benny | Aziz Ansari | Don Rickles | Godfrey Cambridge | Eric Idle | David Cross | Stewart Lee | Samuel Beckett | Jerry Lewis | Joanna Lumley | Jerome K. Jerome | Phil Silvers | Edward Lear | Tony Hancock | George Carlin | Stephen Colbert | Tina Fey | Keith Allen | Russell Brand | Michael Cera | Stan Laurel | Ricky Gervais | Gilda Radner | Larry David | Chris Pontius | Dave Chappelle | Jimmy Finlayson | Paul Reubens | Peter Sellers | Buster Keaton | Flann O’Brien | Lenny Bruce | Sacha Baron Cohen | Steve Coogan | PG Wodehouse | A.J. Liebling | Curly Howard | Fran Lebowitz | Charlie Kaufman | Stephen Merchant | Richard Pryor | James Thurber | Bill Hicks | ALSO: Comedy and the Death of God

On his or her birthday, HiLobrow irregularly pays tribute to one of our high-, low-, no-, or hilobrow heroes. Also born this date: John Kenneth Galbraith and Italo Calvino.

READ MORE about members of the Psychonaut Generation (1874–1883).