De Condimentis (1)

By:

September 7, 2010

Editor’s note: This is one of the most popular posts, traffic-wise, ever published on HiLobrow. Click here to see a list of the Top 25 Most Popular posts (as of October 2012); and click here for an archive of all of HILOBROW’s most popular posts.

Introducing a series of posts — by independent scholar Tom Nealon — revealing the secret history of our condiments.

Condiment: from L. condimentum “spice, seasoning, sauce,” from condire “to preserve, pickle, season” (variant of condere “to put away, store”). As its etymology suggests, a condiment must have a shelf life — which, until recently, means it was vinegar-, salt-, or sugar-based. Also, it must be at least slightly more complicated, and moister, than a seasoning.

However, though preserved, pickles aren’t condiments: pickled beets can be lovely with falafel, but they’re still a vegetable. As for the “usage” folks, who define anything added to prepared food as a condiment, they’re quite mad: even if you dip fish sticks into it, hollandaise is a sauce, not a condiment.

Arising millennia ago after the accidental vinegaring of wine, though they’ve never been too far from our hearts or mouths, condiments have been forgotten, disdained, taken for granted. In Reay Tannahill’s pioneering study Food in History, the index shows exactly zero mentions of condiments. The supposedly encyclopedic Larousse Gastronomique devotes one-third the space to condiments as it does to confit on the facing page. In his otherwise terrific On Food and Cooking, Harold McGee parrots the middlebrow hierarchy (from worst to best) seasoning, then condiment, then sauce.

Yet condiments are the half-feral adjunct to the food on your plate — they insist and intrude, add and subtract! They are the demi-mad building blocks of cuisine, the stab of flavor that reminds us why we eat. True, in the wrong hands and on the wrong dish they can ruin, mask, dumb down. But the real reason that the powers that be have taken such pains to shunt them, literally and conceptually, off to the side, is this: condiments represent and encourage the democratic power of the individual to decide how to eat.

From ancient Rome through the middle ages

The Romans took from Greece two condiments (garum and liquamen) made by crushing and fermenting in salt the innards of various fish, and turned fish sauce into a booming industry. (Note: confusingly, the term sauce is often used not as a culinary term of art, but instead descriptively, as with brown sauce, steak sauce, Worcestershire sauce, tartar sauce, soy sauce. Like fish sauce, these are condiments.) Every Roman dinner table featured a bowl of this fish sauce, and almost every dish had some in it. Apicius, the cookbook compiled from 4th/5th-century Roman cuisine, boasts an entire section devoted to condiments (De Condimentis). There was a version of fish sauce for almost every social class — each descending level made from worse, and possibly more revolting, fish parts. Nowhere else or since — save perhaps for chutneys in Indian cuisine and ketchup in late 20th century America — has a condiment occupied so central a place in a culture’s cuisine.

During the long decline and transformation of the Roman Empire, condiments entered into a dark age of their own. Roman roads, and more importantly, the Roman view on trade, spread the building blocks of condiments across Europe. Salt, sugar, and vinegar are all processed goods, and the collapse of the system that had processed them so effectively — and hastened their safe movement — left Europe without the infrastructure to make condiments, even if they had wanted to. The West was left without the vast machine that had sustained the fish sauce and vinegar industries; condiment usage retreated east to the chutney of India and the soy and fish sauce of China and Southeast Asia.

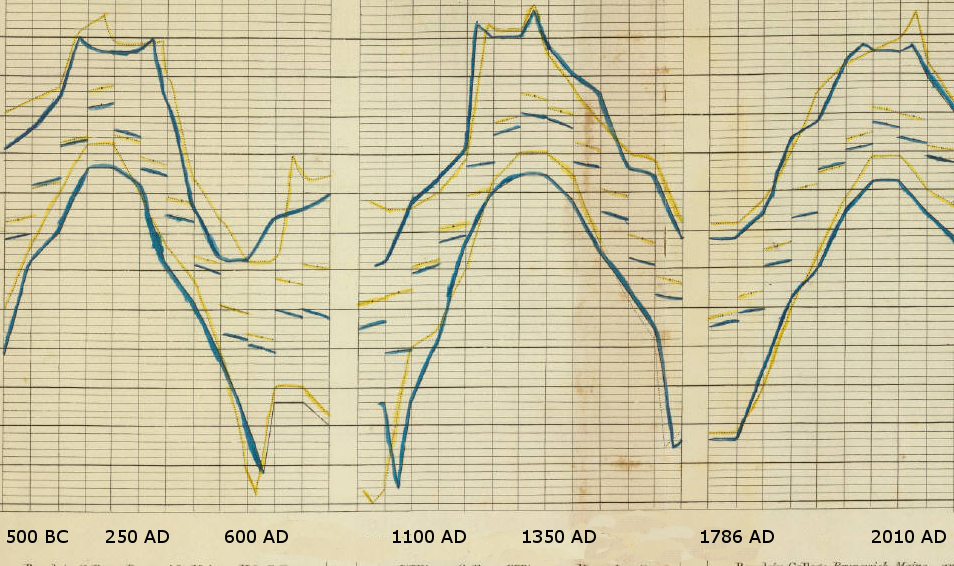

As demonstrated on the graph below, the fall of Rome led to a long decline in condiment use, followed by a “dead cat bounce” beginning around 750 AD — no doubt resulting from the founding of Islam and the subsequent rise of tahini. Interesting to note is that condiment popularity (the blue lines) and condiment diversity (yellow) follow similar historical patterns. You’ll notice that brief spikes in condiment diversity seem to be a good predictor of historical events — the fall of Rome, the tahini bubble, and the collapse of the housing market were all preceded by spikes in condiment diversity.

Though under feudalism, a monarch’s power may have been absolute, his methods of control were extremely limited. Thus, though autocracy is generally bad for condiment choice (though often good for condiment innovation) the middle ages proved a fertile ground for the rebirth of condiments in both respects.

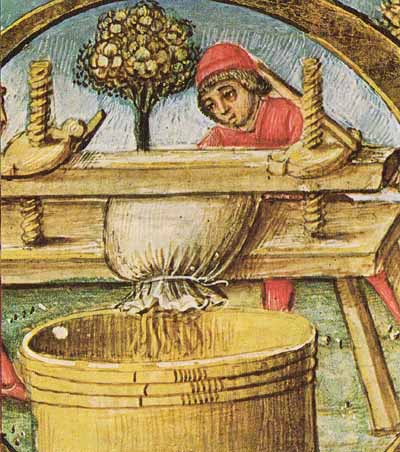

During the middle ages, vinegars and verjuice (a quasi-vinegar liquid made from unripe grapes) were easy to find, and a slowly emerging middle class was on the look out for ways to make its food taste better. Proto-sauces, many of which ended (and disappeared) as condiments — cameline and garlic cameline (cinnamon sauces often available pre-packaged in the 14th century), galantyne (a ginger/wine sauce), poivre jaunet and noir (green and black pepper sauce), caudell (a spiced wine), even an early honey mustard sauce that I’ve prepared — were plentiful. It was truly a golden age.

“Therefore if a thing is to be pleasing and harmonious unto us… it must be seasoned with the condiment of Thy Wisdom,” wrote the medieval mystic Thomas à Kempis. Alas, like Catharism, Heliocentrism and other medieval heresies, the condimental movement could not be allowed to flourish unchecked.

From the Renaissance through the 18th century

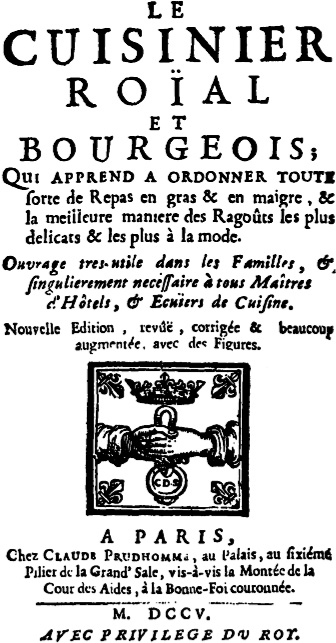

The Renaissance brought an end to this profusion of dipping and daubing. Beginning in the late 16th century, professional cooks took over the writing of cookbooks. For example: Bartolomeo Scappi, Opera dell’arte del cucinare (1570); Marx Rumpolt, Ein New Kochbuch (1581); and later, but notably, François Pierre de la Varenne’s Le cuisinier françois (1651). The rise of haute cuisine, coupled with the rise of modern capitalism, proved more than condiments could bear.

During the early modern and modern eras, cooking both at court (“royal” cookery) and at home (“bourgeois” cookery) became big businesses. The notion that people — even rich people — ought to be allowed to decide how they would eat was anathema. In autocratic France, cuisine reached such heights of sybaritic nonsense that condiments, from a culinary standpoint, essentially didn’t exist. Through insidious means of influence (as opposed to overt coercion), counts were dissuaded from even thinking about having mustards on the table, and lawyers ceased to tinker with their veal roasts. No wonder the bourgeois philosophes supported the Revolution; the Napoleonic Code is a famously condiment-friendly document: “Moveables in their nature are bodies which may be transported from place to place, whether they move themselves like animals, or whether like inanimate things, they are incapable of changing their place, without the application of extrinsic force” (528, often called “le droit condiment”).

Condimental flourishing seems (as history has shown) not unrelated to the overthrow of church and state. So if condiments couldn’t be suppressed, then the powers that be were forced to figure out means of neutering their revolutionary potential — rendering them tasty, but harmless. In the second volume of Democracy in America (1840), Tocqueville warned that a new, subtle form of tyranny was even then emerging in America: a despotism “more extensive and more mild” than any in antiquity, one powerful enough to “dictate and manage the lives of each and every [citizen].” Tocqueville was obviously talking about tomato ketchup.

From the nineteenth century to the present

Nineteenth-century American cookbooks did not embrace Revolutionary France’s faith in condiments; they’re largely silent on the subject. Tellingly, however, tomato ketchup (a non-Newtonian fluid based on a Chinese fish sauce recipe) was invented shortly after the French Revolution. See below.

Worcestershire Sauce, another vaguely disguised fish sauce (this one containing anchovies), was invented in England by two dispensing chemists, John Wheeley Lea and William Henry Perrins, around the same time that Tocqueville was worrying about the mild dictatorship of American ketchup — it was commercialized in 1837.

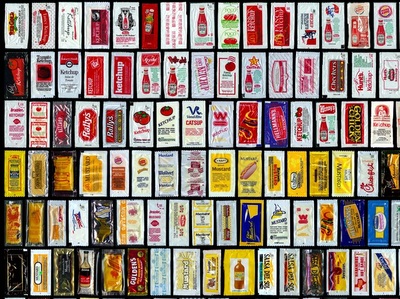

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Western world saw a dizzying increase in condiment choice even as condiments became increasingly homogeneous. The forces of Middlebrow demanded that highbrow sauces be dumbed down into so-called condiments like commercial mayonnaise and bottled salad dressing. (Anyone who has arms can mix oil, vinegar, lemon, salt, and pepper into a salad dressing; why are bottled varieties so ubiquitous?) Ketchup’s only gift to American food — the umami flavor it shares with soy and fish sauce — was lost when high-fructose corn syrup was added. Hot sauces have fared better, though many are bland — hot, yes, but with little character, because capsaicin, the active component of chili peppers, is injected directly into the mix. Mustard, at least, has continued to muddle by.

Today, you can tell how strongly a man or woman yearns for freedom by counting the condiments in his or her refrigerator. (I count 38 in mine.) Sadly, our systematically dumbed down, castrated, and fructosed condiments won’t help us control our eating experience; instead, they have become the illusion of control, a means of controlling us.

In a series of posts planned for this fall and winter, Tom Nealon will analyze one condiment after another. Stay tuned!

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.