TAKING THE MICKEY (12)

By:

February 2, 2020

One in a series of 15 posts surfacing and dimensionalizing the unspoken norms and forms encoded in Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse character. Research and analysis conducted by Josh Glenn in preparation for his appearance in the 2022 documentary The Story of a Mouse.

TAKING THE MICKEY: MINSTREL MICKEY | TRICKSTER MICKEY | A GOOD AMERICAN | HIGH-LOWBROW MICKEY | ICONIC MICKEY | NEOTONIC MICKEY | DONALD STEALS THE SHOW | MICKEY’S DORK AGE | FORTIES BACKLASH | DISNEY CO. MASCOT | FIFTIES BACKLASH | SIXTIES BACKLASH | “I’M THE MOUSE” | NOBROW MICKEY | TAKING THE MICKEY. Also see the series MOUSE: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

As our survey moves through the cultural era known as the Sixties (1964–1973, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema), we’ll discover antiwar activists and other progressive types deploying Mickey as a whipping boy — i.e., a hapless symbol of everything they disliked about the USA. If in the MM backlash of the Fifties, one can discern frustrated affection for Mickey Mouse, the Sixties backlash is more mean-spirited.

As seen in the previous installment in this series, the Fifties took the MM critique in two directions. Disapppointed that MM had become a Disney Co. mascot, Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman portrayed him as a greedy, cutthroat capitalist who’ll do whatever it takes to triumph. Ed “Big Daddy” Roth took the backlash in a different direction: MM had ceased to be a trickster, he’d become too goody-goody and all-American; therefore, let’s degrade MM, let’s portray him as a countercultural freak. As we’ll see in this installment, during the Sixties these two MM backlash options were taken to extremes.

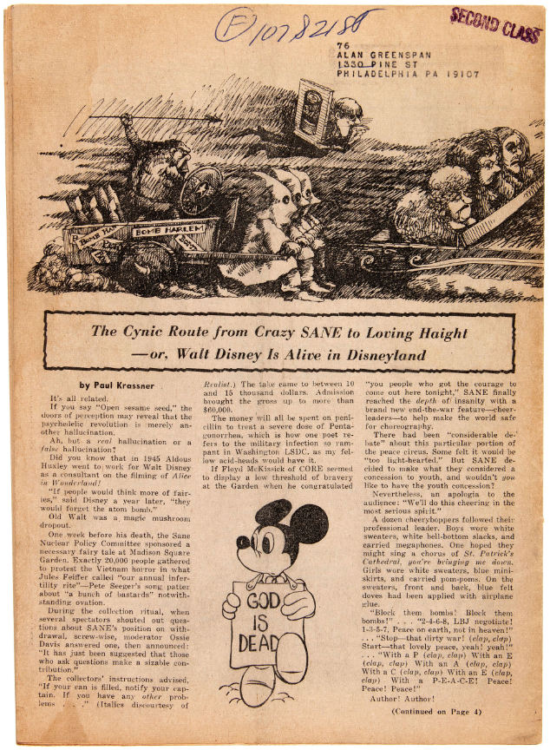

When George W.S. Trow laments, in his 1980 essay Within the Context of No Context, that parody — as practiced during the Sixties and Seventies, by members of the Anti-Anti-Utopian (1934-43) and Blank (1944-53) generations — is an art form for “children who have had imposed upon them a meaningless iconography,” he’s talking about the sort of parodies you’ll find in this post. Trow, who was born (in 1943) on the cusp between these two generations, may well have agreed with Paul Krassner, Heinz Edelmann, Robert Grossman, Dan O’Neill, Robert Armstrong, even his friends Henry Beard and Douglas Kenney (with whom he’d collaborated on The National Lampoon) that since the Thirties, Mickey Mouse had become an example of meaningless iconography. What discouraged him was the petulant quality of his peers’ parodic efforts.

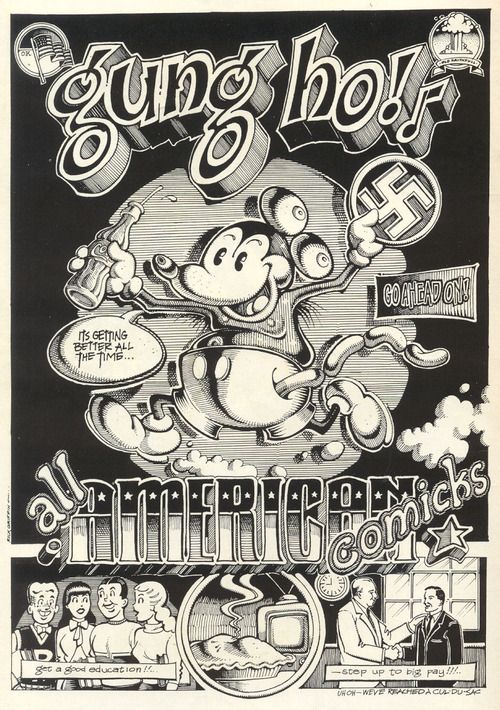

I sympathize with Trow’s critique of Sixties- and Seventies-era parodies. On the other hand, we should try to grok what Krassner, Edelmann, Grossman, O’Neill, Armstrong, et al., were trying to accomplish with their MM parodies. Theirs was a counter-hegemonic guerrilla insurgency, aimed at exorcising not simply Mickey Mouse but what he represented — a gung-ho, cheery American patriotism disguising the efforts of America’s military-industrial complex to win hearts and minds not only globally, but here in the USA. Fun fact: In 1965, when protesters turned out for Seattle’s first major demonstration against the Vietnam War, counter-protesters jeered them by singing the “Mickey Mouse Club” anthem.

Mocking MM, during the Sixties, was implicitly — sometimes explicitly — understood as a means of freeing people’s minds.

Above: “Forest Lawn Cemetery, Los Angeles” — an evocative, slightly eerie 1964 photo by Garry Winogrand.

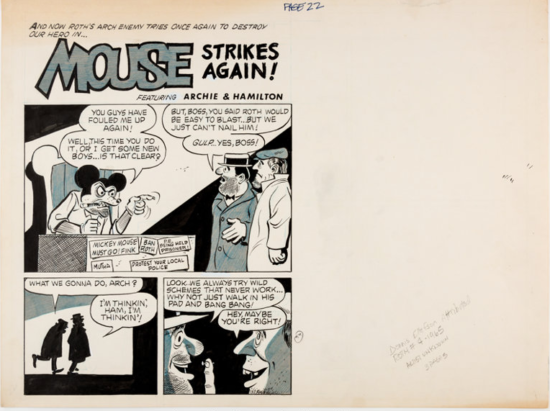

The fourth (and I believe final) issue of Big Daddy Roth magazine (1965) features the comic “Mouse Strikes Again” — which positions a cigar-chomping, mafioso-ish Mickey Mouse as “Roth’s arch enemy.” MM sends two inept hit-men to fulfill a contract on Big Daddy.

A nice example of a “cusp” phenomenon — bridging the MM backlash of the Fifties and Sixties. The critique of MM, here, is that he’s become a corporate stooge — a rapacious capitalist.

Art Hoppe (born 1925) was a popular columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle for more than 40 years. He was known for satirical and allegorical columns, including one dated November 19, 1965 — shortly after Walt Disney announced the ambitious Disney World project in Orlando, Florida — in which he predicted a dystopian future America controlled by Disney.

Excerpt:

In 1973, when an electronically operated Congressman rose before a crowd of applauding tourists in the galleries to propose changing the name of the nation to “the United States of Disney Country,” the measure passed unanimously.

Actually, the Disneyans, as citizens were now called, lived much the same lives as before. They spend their days riding around in cars and their evenings being entertained by various machines, such as one that simulated live people moving about on a screen and another that simulated the music on magnetic tape.

The Disneyans still thrilled to the exploration of space. But they did so in simulated rockets. And they still plunged into the exotic watery depths, but in simulated submarines in artificial concrete pools. All of which was much safer.

The nation was open from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day of the year and the annual festivals to Mickey and Minnie Mouse and the Great Dog Pluto attracted pilgrims from all over the world.

The war in Vietnam ended in its 53d year with the conversion of that country to Jungleland. (The ride through the Mekong Delta with stuffed Vietcong firing blanks from the riverbanks proved the greatest attraction.) And with the establishment of Disneygrad the following year, it was only a matter of time before the entire world became a wholly owned subsidiary of Disney Enterprises, Inc.

And what a utopia it was – neat, clean, orderly, with enough simulated thrills and artificial adventure for one and all.

Well, almost all. There was one old man (no one else ever grew old) who missed the past. “I miss tears,” he said, “and automobile horns and the smell of manure and the common cold and dandelions and getting drunk and how you feel when someone dies.”

Note that a 1937 New York Times Magazine essay by Herbert Russell had suggested something along the same lines:

Can it be possible that Mickey is waiting patiently for the collapse of civilization, waiting until the nations have pulled down their house of cards and destroyed all their own pretensions? Does he believe that the broken and oppressed people, wallowing in despond, will then turn to the one person whom they can depend upon for that happiness, and demand that Mickey shall become Emperor of the World? Perhaps Mickey isn’t so dumb as he looks. Maybe that is why he is winning the ordinary folk and the great, building his youth movement through clubs, boring from within in Europe, Asia, Africa, India and the Americas.

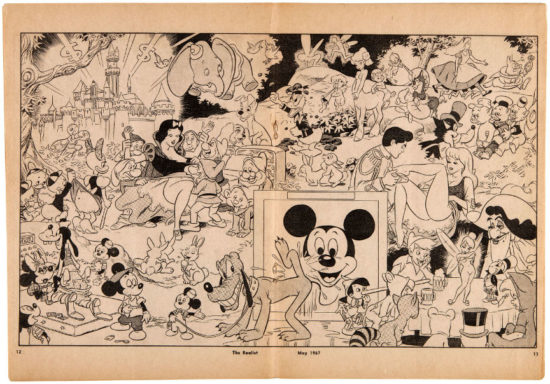

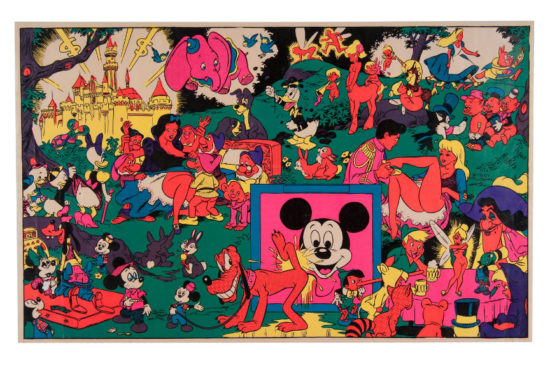

The May 1967 issue of The Realist, a magazine of social-political-religious satire published by Yippie co-founder Paul Krassner (born 1932), featured a satirical, grotesque centerfold cartoon drawn by Wally Wood (born 1927), one of MAD‘s founding cartoonists.

The Disneyland Memorial Orgy poster includes depictions of — I’m quoting from an auction house’s description — “Disney characters engaged in various sexual acts along w/other perverse and drug-related activities. Characters pictured include Mickey and Minnie Mouse, Donald and Daisy Duck, Goofy, Pluto, Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs, Three Pigs, Cinderella, Alice, Dumbo, Lady and The Tramp, plus characters from Peter Pan, Fantasia, others. Scenes include Tinker Bell as a stripper, Pluto urinating on a picture of Mickey, Minnie as a prostitute w/Goofy, Mickey doing drugs, etc.”

Pluto urinating on a picture of Mickey was, if you will, a pop-culture version of burning the Stars and Stripes. Wood’s infamous orgy scene was a hit among the magazine’s readers, so Krassner published it as a stand-alone, color poster. Pirated versions of the poster could soon be found in headshops — the ground zero of snarky parodies of meaningless iconography, individually clever but collectively depressing — across the country.

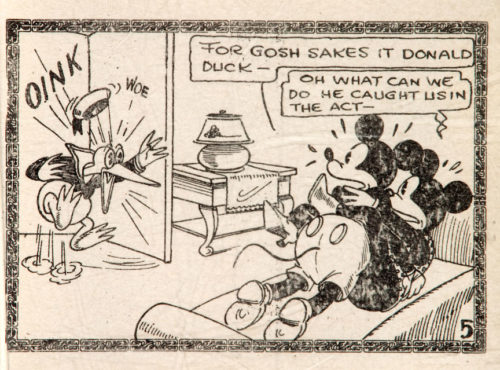

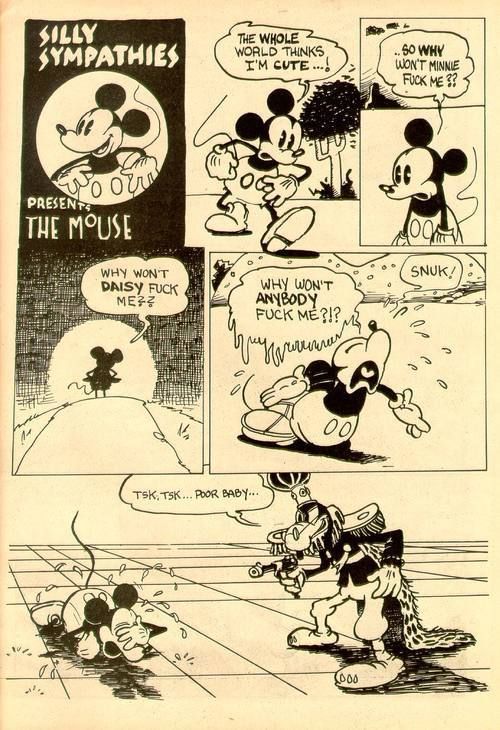

PS: Not only is this poster juvenile and stupid, it’s not even original. Disney-themed “Tijuana Bibles,” c. 1938–1943, put Mickey and Donald in compromising positions. These earlier X-rated comics — sample panel, below — strike me as funnier than anything produced during the Sixties.

Below: A Tijuana Bible-influenced black-lite poster, c. 1970.

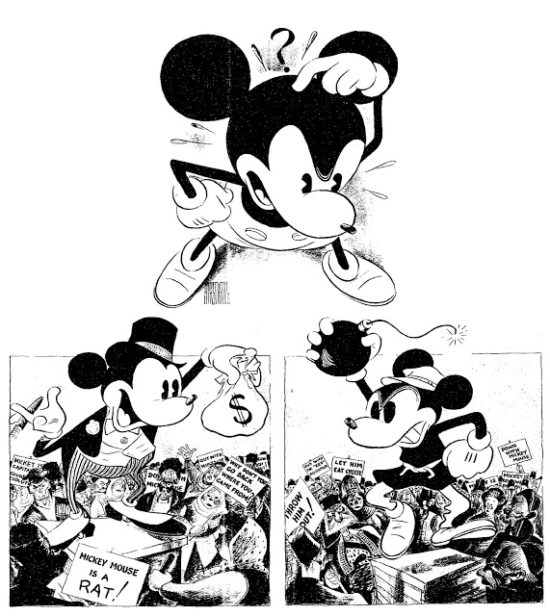

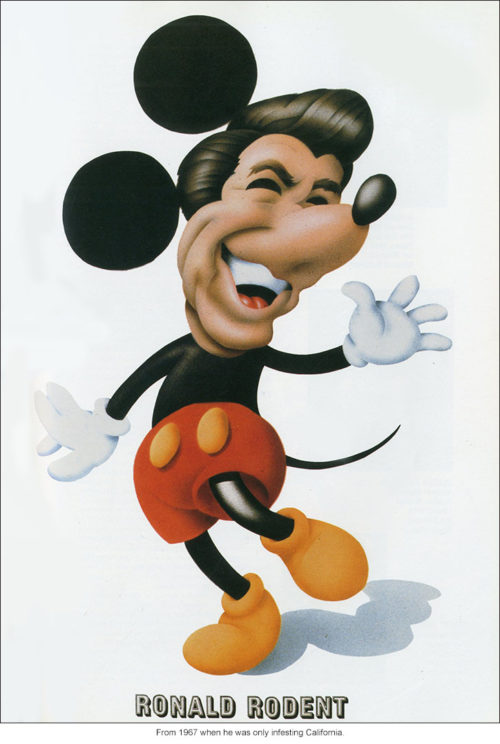

Also in 1967: Political cartoonist Robert Grossman caricatured California’s newly elected governor, Ronald Reagan, by portraying him as “Ronald Rodent,” an ebullient MM-like figure. “Reagan seemed to me to have the cuteness of Mickey and he managed to maintain it the whole time he was in public view,” Grossman would snarl, some years later, when asked to explain the image. “I think it was the secret of his success: that he managed to embody a certain ‘lovable’ quality.”

Like MM, Grossman’s image would have us understand, RR had been shaped and polished into a cheery, gung-ho mannequin deployed by sinister forces in order to sell us a bill of goods.

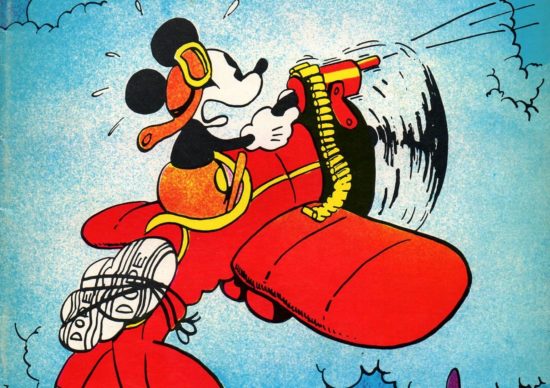

The following year saw the release of the British animated movie Yellow Submarine, art directed by the German designer and illustrator Heinz Edelmann — who, along with Milton Glaser (cf. Glaser’s 1966 Bob Dylan poster), Peter Max, and Seymour Chwast, is now credited with pioneering the psychedelic style of illustration and design. The films’ villains, the Blue Meanies, have blue skin, claw-like hands and wear black masks; their Chief, known as “His Blueness,” wears a hat with rabbit-like ears — while the rank and file Blue Meanies sport what appear to be Mouseketeer caps.

The Mouseketeer/Meanies overrun the idyllic Pepperland — forbidding all forms of pleasure, most particularly in the form of music. The Beatles to the rescue! At a not-so-subliminal level, Yellow Submarine uses Pepperland as a stand-in for Disneyland, and Disneyland as a stand-in for… America, the West, the world. According to this gnostic vision, trapped inside the shitty social order that we currently inhabit is a beautiful, peaceful, authentic version of the world we are meant to inhabit. It requires liberating! (I’ve written more about Yellow Submarine‘s gnosticism here.)

Note that two years later, a mob of some 300 American long-hairs — compelled, perhaps, at a pre-conscious level by Yellow Submarine — would occupy Disneyland. More on this incident, below.

One more note on Edelmann vs. MM: In 1970, he would illustrate a German children’s book, Maicki Astromaus, It’s an updated version of a satirical 1941 sci-fi story by Fredric Brown — in which a German rocket scientist sends his mouse-assistant, Mitkey (named in honor of the “original Mitkey Mouse, by Valt Dissney”), to the moon. Mitkey/Maicki encounters a race of tiny aliens… whom he briefs on the absurdities of human civilization.

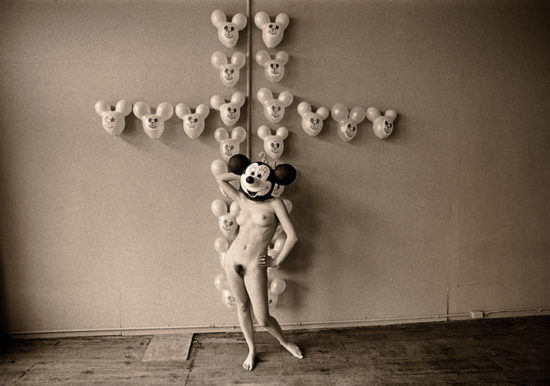

Shown above: “The Static Electric Effect of Minnie Mouse on Mickey Mouse Balloons,” a 1968 “fiction” by conceptualist photographer Les Krims (b.1943).

James Michener’s essay “The Revolution In Middle-Class Values,” which appeared in the New York Times Magazine on August 18, 1968, posited an explicit connection between MM and the war in Vietnam. Writing in an Adorno-esque vein, Michener argued:

One of the most disastrous cultural influences ever to hit America was Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse, that idiot optimist who each week marched forth in Technicolor against a battalion of cats, invariably humiliating them with one clever trick after another. I suppose the damage done to the American psyche by this foolish mouse will not be specified for another 50 years, but even now I place much of the blame for Vietnam on the bland attitudes sponsored by our cartoons. … Fed on the optimistic pabulum of Mickey Mouse, we believed that the good guys always won, no matter how precariously situated nor how faulty their motivations.

Michener’s screed was issued in paperback, in 1969, as America vs. America.

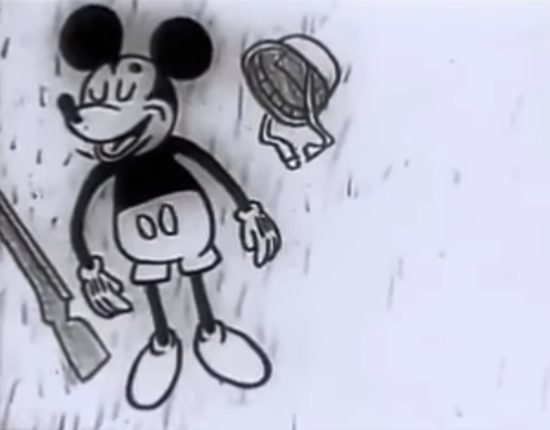

In 1969, Milton Glaser and animator Whitney Lee Savage (best known, today, for creating animated Sesame Street inserts that explained how things work) created a minute-long film that seems inspired by Michener’s critique. Here, MM marches optimistically off to war in Vietnam — and is instantly killed.

Short Subject (often incorrectly titled Mickey Mouse in Vietnam) parodies Disney’s animated WWII-era propaganda films, such as Donald Gets Drafted (1942); Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943), The Spirit of ’43 (1943), and The Old Army Game (1943). The music used in the soundtrack is Herbert Chappell’s polka-style instrumental “The Gonk,” later popularized by George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978).

Produced in 1968 for The Angry Arts Festival, the film was presumed lost until it resurfaced on YouTube a few years ago. In a BuzzFeed interview at the time, Glaser explained: “Mickey Mouse is a symbol of innocence, and of America, and of success, and of idealism — and to have him killed, as a soldier is such a contradiction of your expectations. And when you’re dealing with communication, when you contradict expectations, you get a result.”

Fun fact: Adam Savage, co-host of MythBusters, got his start doing voiceover work on his dad’s Sesame Street films.

A more famous parodic production of 1969 is Bored of the Rings, the Tolkien satire created by Henry Beard and Douglas Kenney after they’d graduated from Harvard, but before they founded the National Lampoon.

In this 1969 bestseller, Saruman becomes Serutan (the name of a laxative product, har har), a Walt Disney-like mogul who has screwed over his former business partner, the wizard Goodgulf. Serutan now presides over the Dicky Dragon (e.g., Mickey Mouse) amusement park and entertainment conglomerate.

Long before Pixar stole the idea for the Disney-mocking movie Shrek (2001), in which the villainous Lord Maximus Farquaad builds Duloc, a creepy amusement park, while simultaneously exiling all actually fantastic and wondrous creatures to Shrek’s swamp, we read about Serutan’s Disneyland-like domain:

Down in the low valley lay the pastel pink-and-blue walls of Serutan’s mighty fortress. The entire city was ringed with walls, and around the walls was a pale-lavender moat crossed by a bright-green drawbridge… Beyond the walls the expedition saw the many wonders that had lured countless tourists through its portals in the past.

Amusements of all description lay within: carnivals and sideshows under permanent tents, fairies’ wheels and gollum-coasters, tunnels of troth, griffin-go-rounds and gaming houses where a yokel could lose an idle hour, and, if he wasn’t careful, his jerkin… Everywhere, they noticed, were the brainless grins of Dickey Dragon. Pennants, signs, walls all bore that same idiotic, tongue-lolling face, But now that once-beloved creature had revealed itself to be the symbol of its creator’s lust for power, a power that had to be ended.

In the passage quoted here, Beard and Kenney make explicit the goal of their fellow Sixties MM parodists. Mickey Mouse, beloved icon, has become a monster — a symbol of corporate greed, to those in the know. Wake up, people!

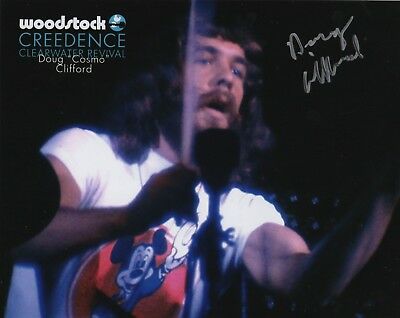

Above; Doug Clifford, drummer for Creedence Clearwater Revival, at Woodstock — 1969.

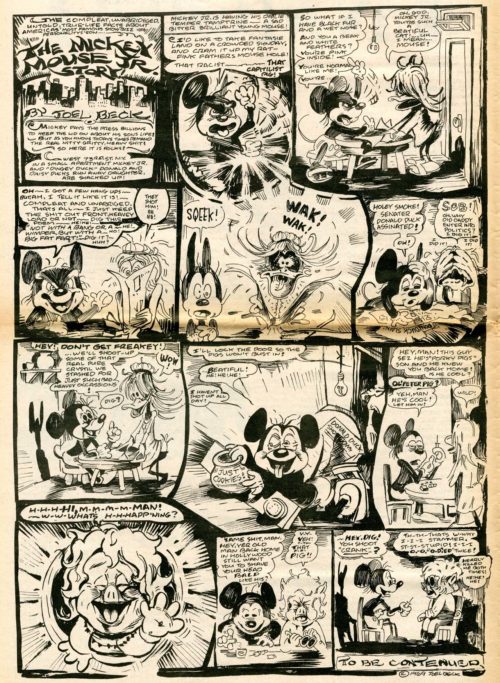

Above: “The Mickey Mouse Jr. Story” (1969) by San Francisco Bay Area artist and cartoonist Joel Beck. (His comic Lenny of Laredo was the first underground comic book published on the West Coast.) Mickey Jr. is a hippie — shacked up with Donald and Daisy’s runaway daughter, in New York — who hates his racist, capitalist father. Who apparently disapproves of the kids’ interspecies relationship. Donald Duck, a senator, is assassinated… at which point the kids shoot up crank with Porky Pig’s hippie son, Peter. Har har.

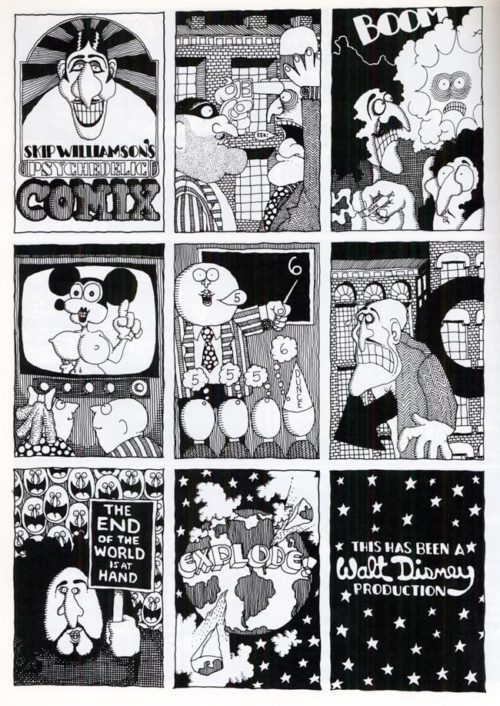

Above: “Skip Williamson’s Psychedelic Comix” — I’m not sure of the exact date. Williamson (born 1944) was a central figure in the underground comix movement; his best-known character is Snappy Sammy Smoot.

In a 1986 conversation with Grass Green, conducted for The Comics Journal, Williamson had the following to say about Disney:

My earliest memories were that I wanted to draw cartoons. I would get in trouble when I was in grade school for drawing Mickey Mouse instead of doing my homework. … Walt Disney was the first major early influence that I can remember. Of course, Snow White came out before I was born, but as soon as I could see, Snow White, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, Uncle Walt ran it. Disney was probably, culturally, the most important influence on the country at a certain formative period because he caught all the baby-boomers. He caught all the little rug rats like you and me, and he twisted our minds into a never-never land mindset. … One of the good things about Disney was that he put all those wonderful German and Teutonic illustrators to work. He hired the best people, which was wonderful in terms of style. Unfortunately, he chose to become homogenized and politically he was reactionary. But his early work was excellent, and I think that was kind of the hallmark for the generation.

He’d go on to say: “The Warner Bros. post-war cartoons were great. Better than Disney because of their sense of insanity.”

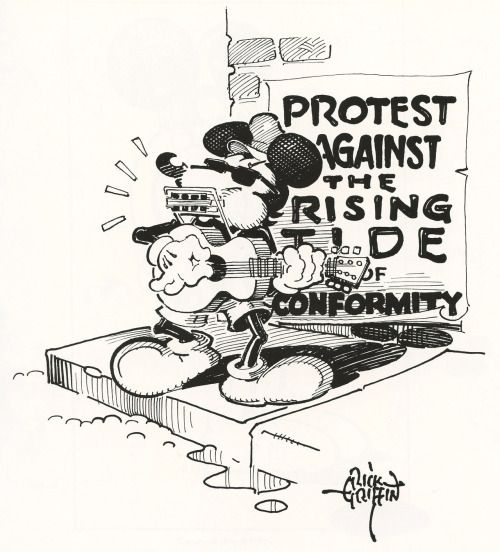

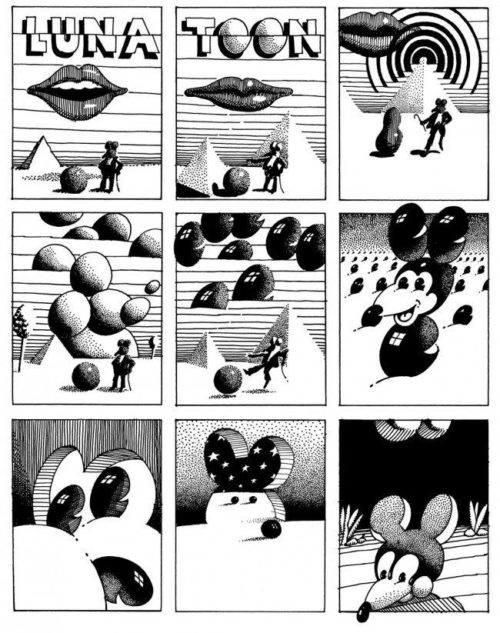

Along with Alton Kelley, Stanley “Mouse” Miller (whose nickname derived from his early fascination with MM), Victor Moscoso, and Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin was one of the “Big Five” of psychedelia. In 1967 they founded the Berkeley-Bonaparte distribution agency to produce and sell psychedelic poster art. Here are a few MM-themed works from this group.

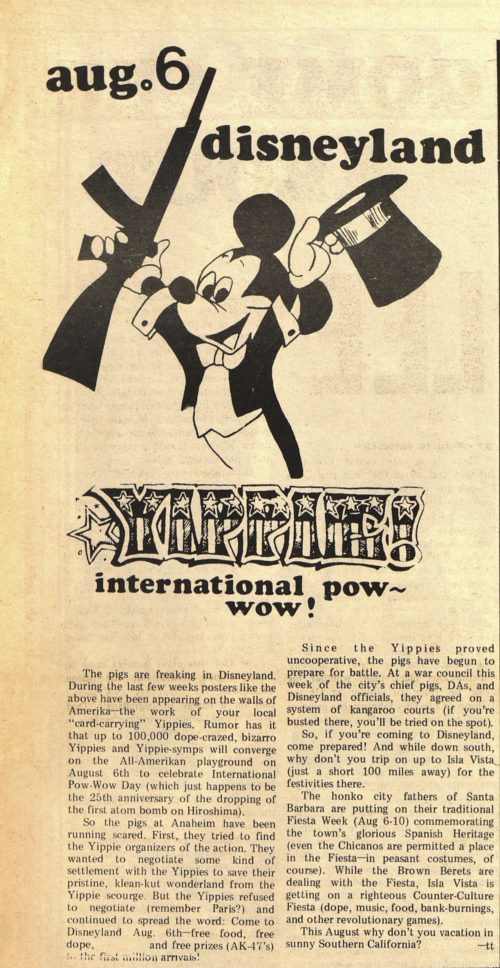

In 1970, perhaps impelled by the subtext of the movie Yellow Submarine (see above), some 300 young antiwar activists chose August 6, 1970 — the 25th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima — to stage a protest at Disneyland. The goal of “International Pow Wow Day” was consciousness-raising. People needed to know that Disneyland’s major sponsor, Bank of America — through affiliations with the defense contractors Litton Industries and McDonnell Douglas — was helping to finance military atrocities in Vietnam and elsewhere.

Yippie activists distributed half-joking leaflets proposing all sorts of provocative demonstrations to take place at Disneyland. In the event, not much actually happened. Hundreds of long-hairs smoked pot, chanted “Ho-ho Ho Chi Minh, Ho Chi Minh is gonna win!”, and flew a Viet Cong flag over Castle Rock on Tom Sawyer Island. When they tried to march down Disneyland’s Main Street, the protesters were stymied by riot police.

For a fantasy version of this incident, see the 1973 Yellow Dog comic, described below.

In 1970, the English political caricaturist Gerald Scarfe (born 1936) was sent by the BBC to Los Angeles to work with a new animation technique. While he was there, he created the film A Long Drawn-Out Trip (1971), which helped bring stream-of-consciousness art into the worlds of film and music, and earned him a job directing the animation in Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

“I drew everything American I could think at the time — Coca-Cola, Mickey Mouse, Playboy, Black Power symbols — and then made a film of the images dissolving into each other,” Scarfe would later explain. “There were quite a lot of drugs around at that time so I drew Mickey Mouse smoking a spliff and so on. At the time, I was just doing it for fun and didn’t think it was particularly revolutionary. But when the guys from Pink Floyd saw it they thought I was fucking mad and wanted me to work with them.”

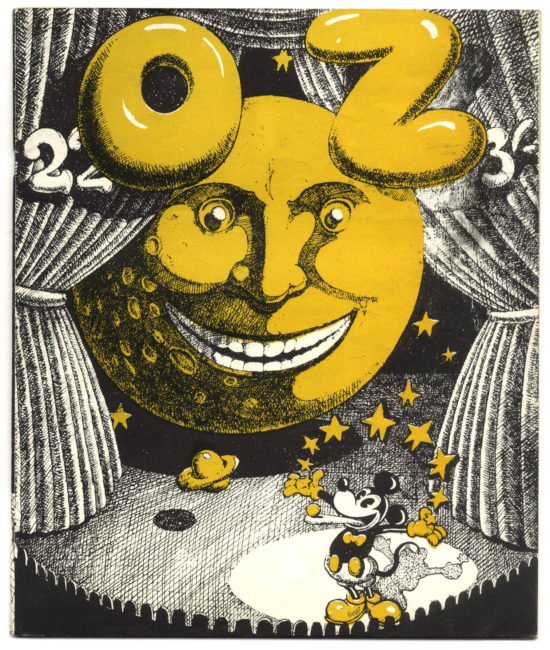

The May 1970 issue of the gorgeously produced British satirical/countercultural magazine OZ was intentionally provocative. Schoolkids OZ, as the issue was titled, was edited by 20 adolescents. One feature, “Rupert Bares All!” — a mashup of the beloved British children’s comic-book character Rupert Bear and an X-rated R. Crumb cartoon — became particularly notorious. The magazine’s editors were charged with conspiracy to corrupt public morals — which carried a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

The then-longest obscenity trial in British history ensued. John Lennon and the “Elastic Oz Band” quickly recorded a one-off single (released July 1971), sales of which supported the defendants. The dashed-off lyrics, mostly “God save us from ___,” were originally “God save Oz from ___,” but Lennon didn’t think that American record buyers would get the reference.

Oh, God save us from defeat

Oh, God save us from the war

Oh, God save us on the street

Let us fight for people’s rights

Let us fight for freedom

Let us fight for Mickey Mouse

Let us fight for freakdom

Oh, God save us one and all

etc.

A musician named Bill Elliot voiced the lyrics. The reference to fighting for Mickey Mouse is the usual snark from Lennon — who delighted in pushing Americans’ buttons by conflating America, Jesus, Mickey Mouse, Elvis, etc.

Fun fact: In 1972, Oz would begin selling the MM badge shown above, via mail order. As mentioned in an earlier post in this series, Fantasia — a flop in 1940 — was rediscovered in the Sixties by potheads who appreciated its proto-psychedelic trippiness.

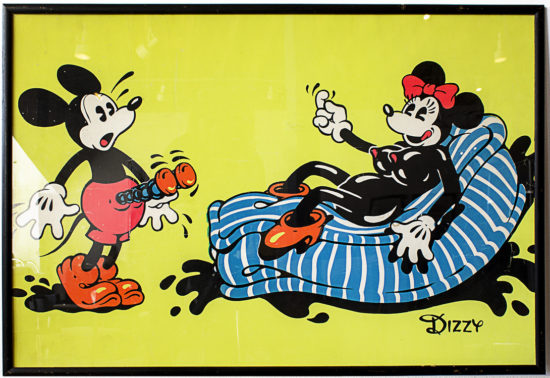

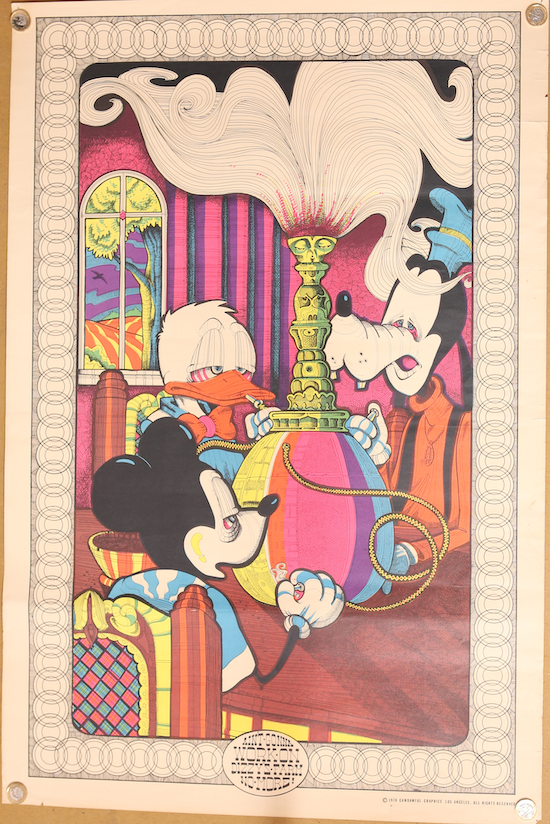

Here’s another example of supposedly hilarious headshop anti-MM art. Titled “AIN’T GONNA WORK ON DIZZY’S FARM NO MORE,” this black-light poster — credited to Gawdawful Graphics, LA-based creators of posters showing Popeye and Olive Oyl screwing, Nixon taking a crap, Dick Tracy smoking dope, and Dennis the Menace driving a kid-sized hot rod — was produced in 1970. This same outfit also produced plenty of black-light fantasy posters featuring wizards, warriors, and nubile women. According to legend, Disney sued Gawdawful Graphics over this poster, and they went out of business as a result. True?

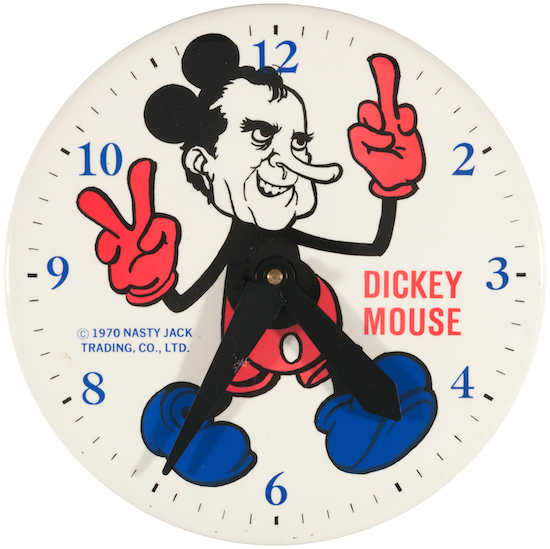

Also: Behold the “Dickey Mouse” wall clock, featuring Nixon as MM. Produced in 1970 by Nasty Jack Trading Co., and sold (presumably) in headshops. This is such a weak effort at parody that it’s not worth discussing.

Above: MM hippie watch, c. 1970. See this helpful blog for more info.

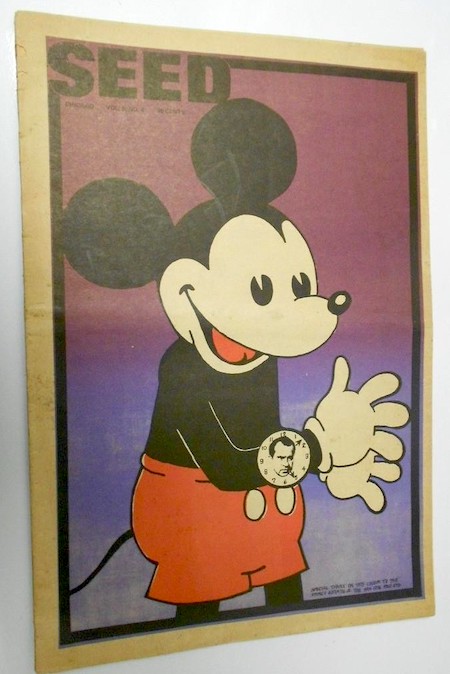

Above: Mickey wears a Nixon watch — har har — on the cover of Seed #4. Not sure of the date of publication — c. 1972?

Above: MM black-light poster c. 1969.

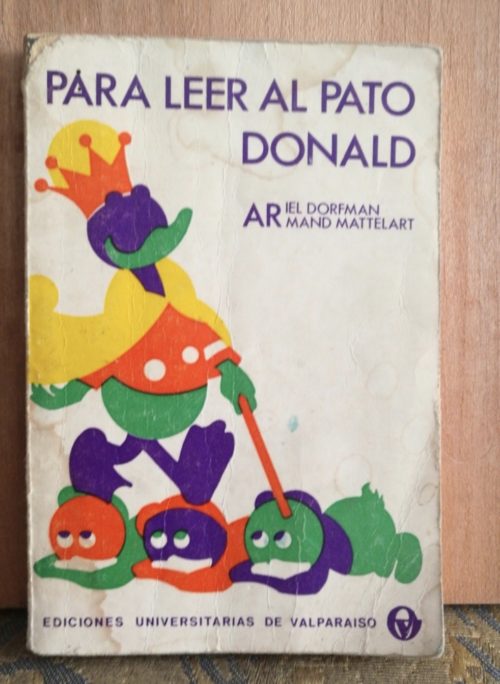

Para leer al Pato Donald (How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comix) is a 1971 book-length essay by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart which critiques Disney comics from a Marxist-semiotic point of view. Dorfman, an Argentine-Chilean writer and human-rights activist best known for his plays, was at the time a cultural adviser to Chile’s President Salvador Allende (ousted in Pinochet’s CIA-supported coup in 1973).

This polemical, paranoid, semi-ironic little tract, first published in Chile, became a bestseller throughout Latin America — and is considered a seminal work in cultural studies. Dorfman and Mattelart’s thesis is that Disney comics are not only a reflection of the prevailing capitalist ideology, but that they are active agents in making Western capitalism seem a natural, normal, and inevitable state of affairs. During Pinochet’s regime, How to Read Donald Duck was banned and subject to book burning.

The book is mostly about DD — as seen in Carl Barks’s excellent comics — but there are a few notes about MM to be found. For example, MM’s roles in MM comics is as a projection of America’s own virtue in the global context:

We could call Mickey’s manner of approaching the world akin to that of a detective, who finds keys and solves puzzles invented by others. And the conclusion is always the same: unrest in this world is due to the existence of a moral division. Happiness (and holidays) may reign again once the villains have been jailed, and order returns. Mickey is a non·official pacifier, and receives no other reward than the consciousness of his own virtue. He is law, justice and peace beyond the realm of selfishness and competition, open-handed with goodies and favors. Mickey’s altruism serves to raise him above the rat-race, in whose rewards he has no share. His altruism lends prestige to his office as guardian of order, public administration, and social service, all of which are supposedly umblemished by the inevitable defects of the mercantile world. One can trust in Mickey as one does in an “impartial” judge or policeman, who stands above “partisan hatreds.”

It’s a great book — highly recommended.

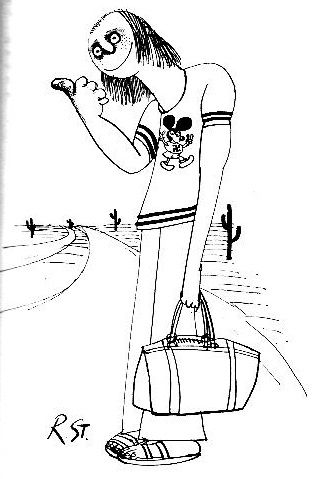

Hunter S. Thompson’s 1971 novel Fear and Loathing — loosely based on two trips to Las Vegas that the author took with Chicano activist and attorney Oscar Zeta Acosta in March and April 1971 — features a scene in which our heroes pick up a relatively naive hitchhiker.

“Can you hear me?” I yelled.

He nodded.

“That’s good,” I said. “Because I want you to know that we’re on our way to Las Vegas to find the American Dream.” I smiled. “That’s why we rented this car. It was the only way to do it. Can you grasp that?” He nodded again, but his eyes were nervous.

“I want you to have all the background,” I said. “Because this is a very ominous assignment – with overtones of extreme personal danger… Hell, I forgot all about this beer; you want one?” He shook his head.

“How about some ether?” I said.

Although Disney and MM are nowhere mentioned in Thompson’s narrative, Ralph Steadman — whom Rolling Stone hired to illustrate the piece, and who a few years later would take his own “fear-and-loathing”-esque trip to Disneyland — depicted the hitchhiker wearing a MM t-shirt.

Was it this image that persuaded the Ramones and others to wear MM t-shirts?

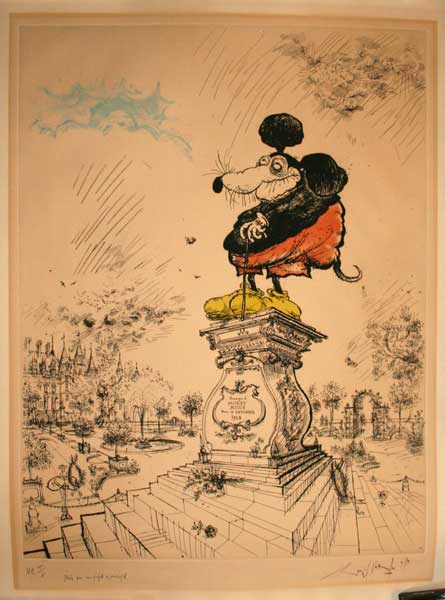

Above: Ronald Searle’s 1971 lithograph “Etude pour un projet municipal.”

Searle (born 1920) was one of the great English satirical cartoonists and illustrators. He is best remembered as the creator of the 1946–1952 gag comic strip series, St Trinian’s, as well as for his collaboration with Geoffrey Willans on the Molesworth books (1953–1959).

Michael Sandle’s (born 1936) bronze installation A Twentieth Century Memorial, begun in 1971 and completed in 1978, was originally titled A Mickey-Mouse Machine-Gun Monument for Amerika. According to the British artist, after he witnessed the National Guard “putting down – very harshly – a student riot at Berkeley UCLA campus against the escalation of the war in Vietnam,” he conceived of this sculpture: a skeletal MM manning a tank’s machine gun. It is in the Tate collection.

A Twentieth Century Memorial began with MM”s head. Sandle’s experimental models of MMs head in clay and plaster led to the development of his 1978 sculpture, Head Mickey Mouse, shown below.

The flayed-looking MM head proved inspirational, to Sandle, who’d later recount that “I had the idea that a decaying cadaver of ‘Mickey Mouse’ would be the right symbol for all that I considered to be rotten within Western Capitalism and its infamous Industrial Military Complex.”

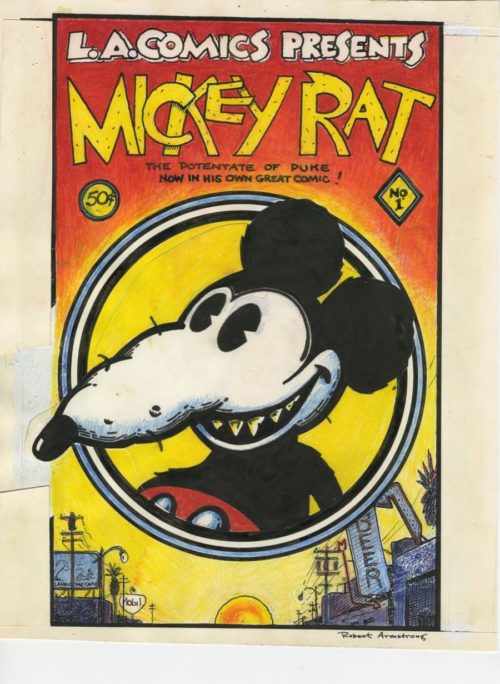

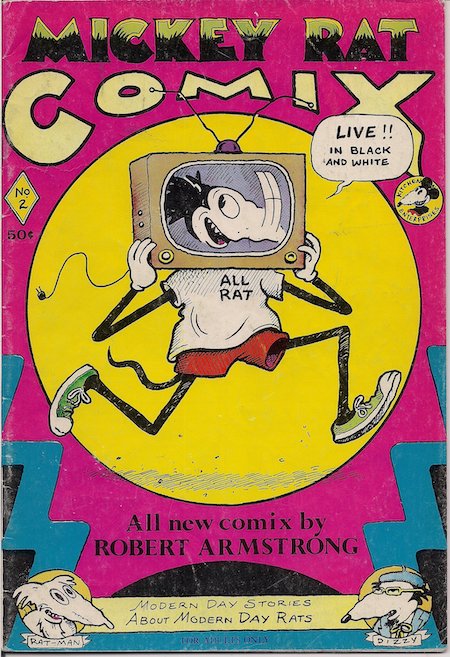

Underground comix artist Robert Armstrong (born 1950) created the sleazy, opportunistic character Mickey Rat in 1971 — as a t-shirt character. The t-shirts were so popular that Mickey Rat appeared as a character in L.A. Comics #1, published that same year; Chester C. Crill wrote the story.

Mickey Rat is an uninteresting character. His sole purpose is to be a shitty version of MM; this is the sort of shallow parody that Trow laments.

In ’71, underground cartoonist Dan O’Neill (born 1942) and several friends — Bobby London, Gary Hallgren, Shary Flenniken, Ted Richards — produced two issues of the comic Air Pirates Funnies, which parodied Mickey Mouse and other copyrighted characters.

O’Neill wrote a long-running comic strip, Odd Bodkins, for the San Francisco Chronicle; in an effort to gain control of the strip’s copyright, c. 1970 O’Neill began working Walt Disney characters into the strip… figuring that the Chronicle would release the copyright for fear of being sued by Disney. (He was fired, instead.)

Calling themselves the Air Pirates — a gang of Mickey Mouse antagonists from the 1930s MM newspaper strip — O’Neill and his comrades (except Flenniken*) depicted Mickey and other Disney characters engaged in sex, drugs, and other adult behaviors. “Throughout my childhood, Mickey Mouse was used as a placebo to lull me into thinking everything was alright,” one of O’Neill’s accomplices stated. “But I found the happy-ever-after world of Walt and Mickey Mouse to be a poor half-truth. Air Pirates shows that Mickey doesn’t always win.”

* Flenniken’s comic strip Trots and Bonnie, which would run for nearly 20 years at National Lampoon, imitated early comic strip artists Clare Briggs and H.T. Webster; she didn’t parody Disney characters.

The publication of Air Pirates Funnies led to a long, highly publicized, expensive legal battle with Disney — which O’Neill counted on. To raise money for the Air Pirates Defense Fund, O’Neill and other underground cartoonists sold original artwork — predominantly of Disney characters — at comic book conventions. The case dragged on until 1978, when the Ninth Circuit ruled against the Air Pirates for copyright infringement,

O’Neill’s four-page Mickey Mouse story Communiqué #1 from the M.L.F. (Mouse Liberation Front) appeared in CoEvolution Quarterly in 1979. That same year, he formed the Mouse Liberation Front. In the late 1980s, O’Neill would sue Disney — claiming that Who Framed Roger Rabbit stole his character Roger, a drug-dealing rabbit who’d appeared in The Realist.

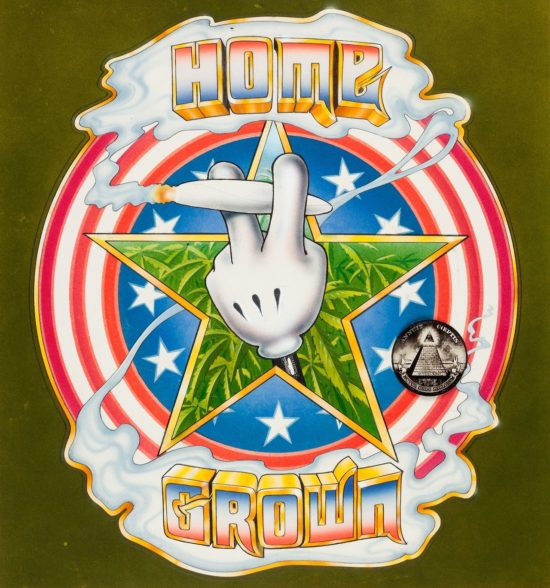

This image of a marijuana cigarette pack, with a “Mickey Mouse” hand holding up a lit joint, was used for countless posters, pinback buttons, metal signs, stickers, t-shirts, wall tapestry fabric posters, and more. Signed only by Alton Kelley, but credited to both Mouse & Kelley.

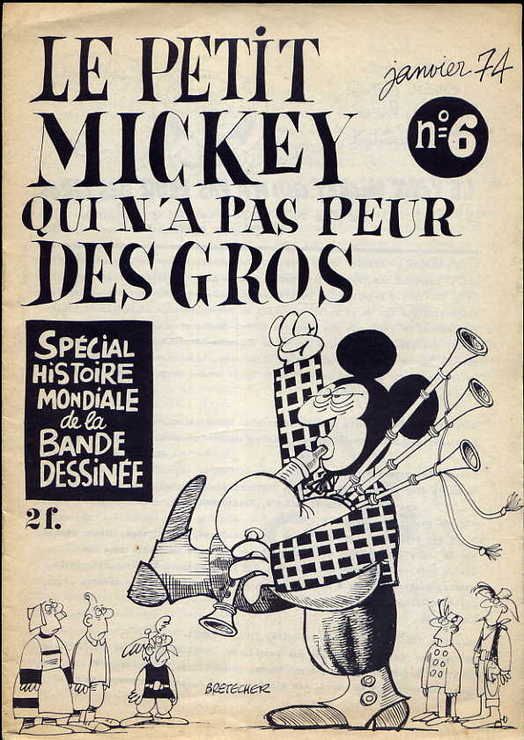

In France, during the Sixties, petits miquets was popular slang for bandes dessinées — that is, comics or comic strips.

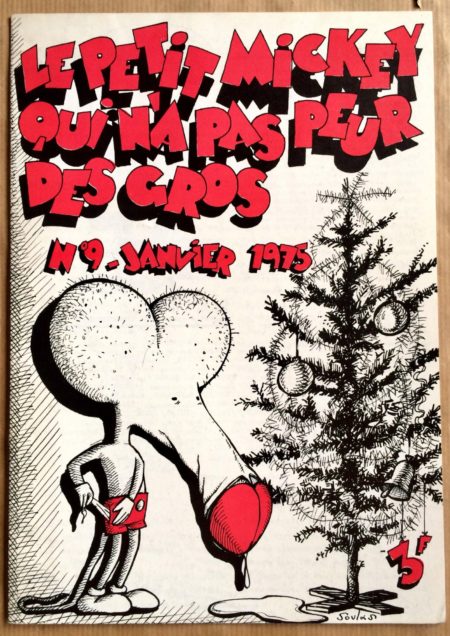

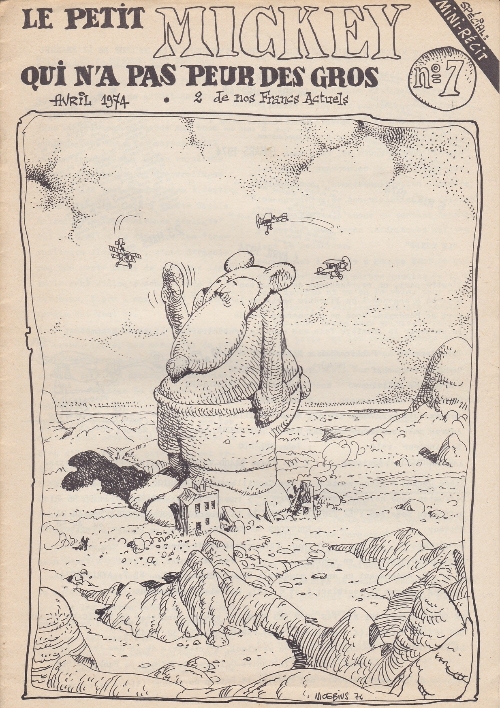

I haven’t been able to find out much about the bande dessinée fanzine Le Petit Mickey qui n’a pas peur des gros, fourteen issues of which appear to have been published c. 1972 – 1978. The only thing I know is that it featured some fun, and sometimes grotesque, covers.

Below: Moebius’s cover illustration for issue #7 (April 1974) would in 1979 be colored by the artist — I guess in order to be sold as a print? Not sure.

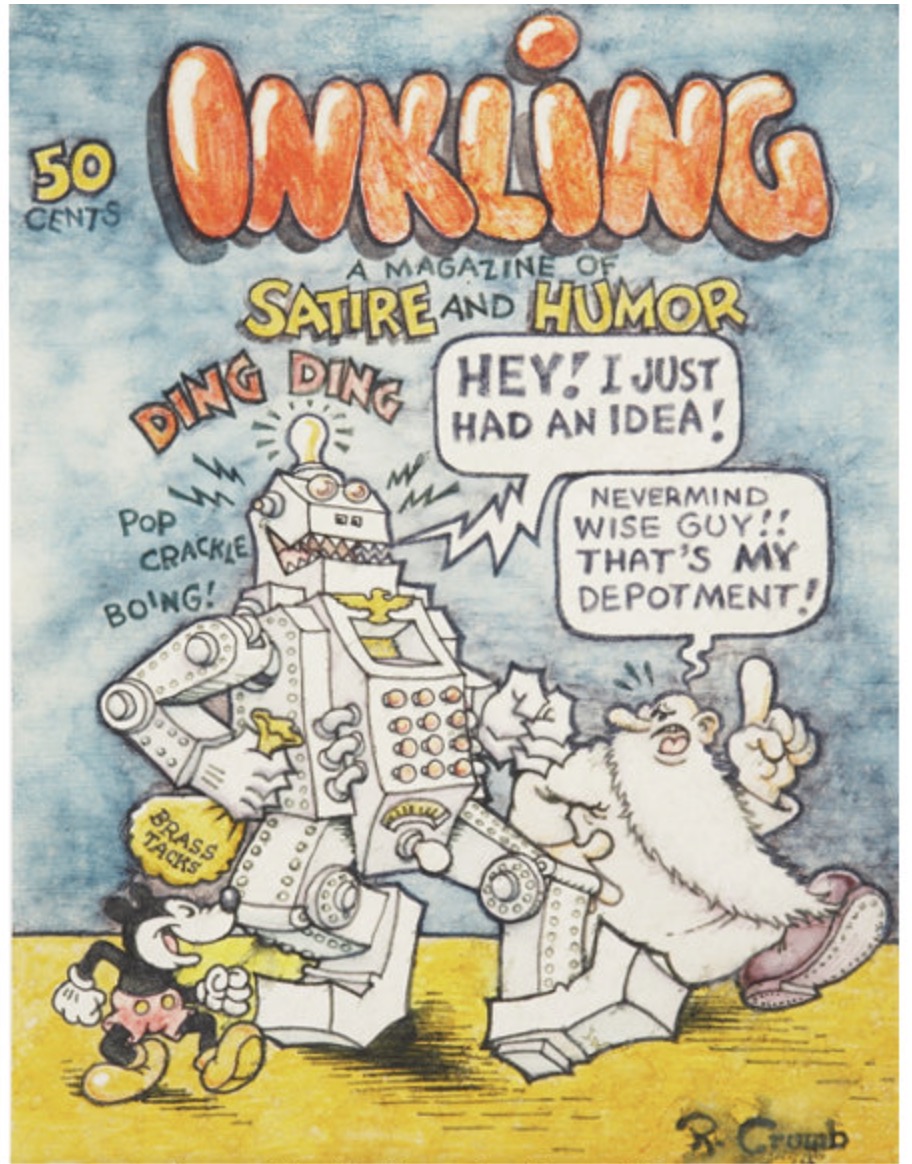

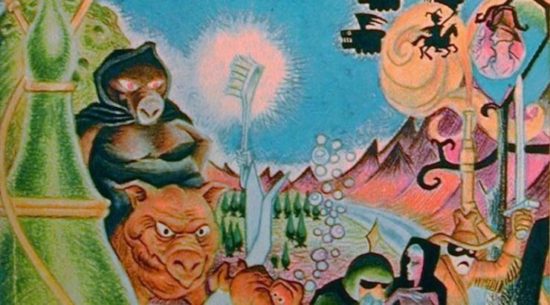

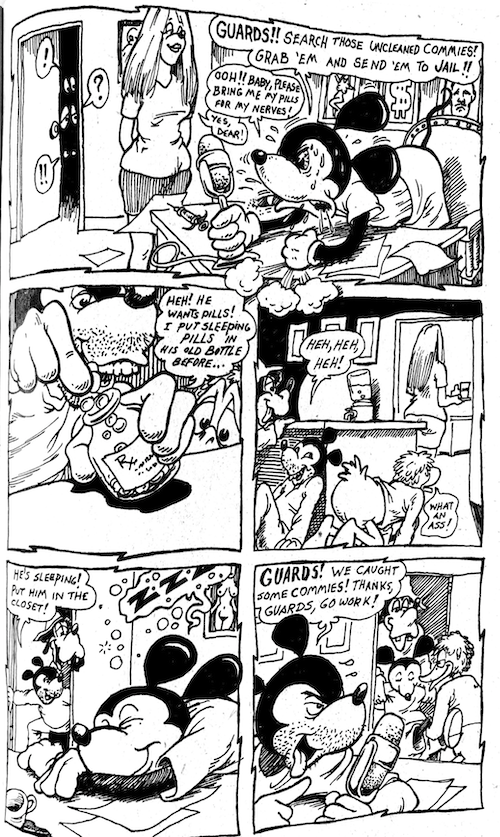

Yellow Dog was an underground comic book (originally, a comics newspaper) published in Berkeley, California from 1968 to 1973. Robert Crumb, Robert Williams, Rick Griffin, Trina Robbins and other notable comix artists of the era contributed. In my collection of Sixties ephemera, I have a copy of issue 24 (March 1973) — which features a 13-page, unsigned comic titled “Mickey Raton Visit the Disneelund.” Throughout this post, we’ve seen MM as a capitalist pig, and also as a dirty hippie. The unsung artist of this, our final example of the Sixties MM backlash, finds a way to give us both at once.

The hippie Mickey Raton (a parody of MM), accompanied by his equally degenerate friends Doggie (Goofy) and Duck (Donald Duck) are motoring through the Californian (?) desert when they spot “Disneelund” in the distance.

Forbidden to enter because of their foul appearance, the hippies sneak in to Disneelund — the emblem of which is a mouse that looks almost exactly like Mickey Raton (except his ears are bigger). Chased by security pigs, they stumble into the tunnels beneath the theme park, climb a ladder, and wind up in the office of MM himself. [PS: This scenario reminds of Hergé’s Land of Black Gold, in which Dr. Müller’s office is connected via trapdoor to a kind of dungeon beneath the house. Just saying.]

MM is depicted as cigar-smoking, pill-popping, capitalist asshole — obsessed with capturing the three “uncleaned Commies” and ejecting them from his park. Mickey Raton dopes MM with sleeping pills, and seduces MM’s secretary/lover, while Duck announces over the park’s loudspeakers that a missile from the military’s nearby testing range is about to strike Disneelund. Har har.

In a 1973 Playboy essay titled “A Real Mickey Mouse Operation,” D. Keith Mano critiqued the Disney Company, post Walt Disney’s 1966 death. In a letter to Playboy, film critic Richard Schickel (author of the harshly critical 1968 book The Disney Version: The Life, Times, Art and Commerce of Walt Disney), chimed in to suggest that “If fascism ever comes to America, it will probably be wearing mouse ears.”

Meanwhile… in literature.

- The Mouse and the Motorcycle (1965) by Beverly Cleary, the first in a trilogy featuring Ralph S. Mouse, gives us an admirable, adventure-loving house mouse.

- Michael Bond’s Here Comes Thursday! (1966), one of a series of books about a mouse named Thursday by the author of the Paddington Bear series, offers a parable about living off the grid. Thursday’s speed, courage, and intelligence allow him to win against humans and cats. The larger lesson is that mouse society thrives when it borrows only what it needs from the human world… and fails when the mice become too human.

- Russell Hoban’s The Mouse and His Child (1967) concerns the quest of a pair of toy mice, joined by the hands and operated by clockwork, to become self-winding. Enslaved and pursued by Manny Rat — a MM-ish villain who rules the dump at the edge of town, our heroes keep moving in the face of defeat, despair, and the riddle of what the purpose of life is, anyway. What does it truly mean to be self-winding?

- Inspired by real experiments, conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH (1971) imagines what might have happened if a group of super-intelligent rats (and one mouse) had escaped the lab and founded a high-tech commune under a farmer’s rosebush. Winner of the 1972 Newbery Medal.

RANDOM STUFF:

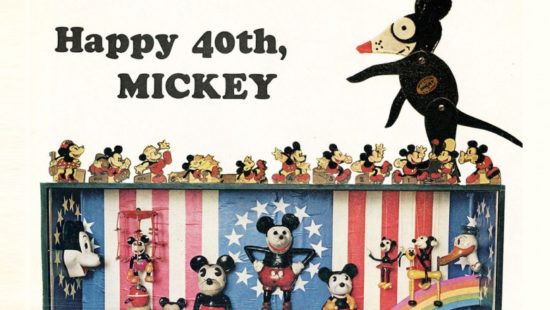

Above: Detail from a 1968 LIFE feature celebrating MM’s 40th birthday.

During the Fifties Maurice Sendak, Roy Lichtenstein, and Peter Saul demonstrated that it was possible to express one’s disappointment with and lingering admiration/love for MM simultaneously, through engaged irony. The next post in this series will take a look at how this approach — which is consonant with Adorno’s prescient critique of Disney characters — continued to evolve during the Sixties and Seventies.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

MORE SEMIOSIS at HILOBROW: Towards a Cultural Codex | CODE-X series | DOUBLE EXPOSURE Series | CECI EST UNE PIPE series | Star Wars Semiotics | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | Show Me the Molecule | Science Fantasy | Inscribed Upon the Body | The Abductive Method | Enter the Samurai | Semionauts at Work | Roland Barthes | Gilles Deleuze | Félix Guattari | Jacques Lacan | Mikhail Bakhtin | Umberto Eco