PRE-MICKEY MICE (2)

By:

April 20, 2023

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1914–1923)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-teens begins c. 1914 and ends c. 1923. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

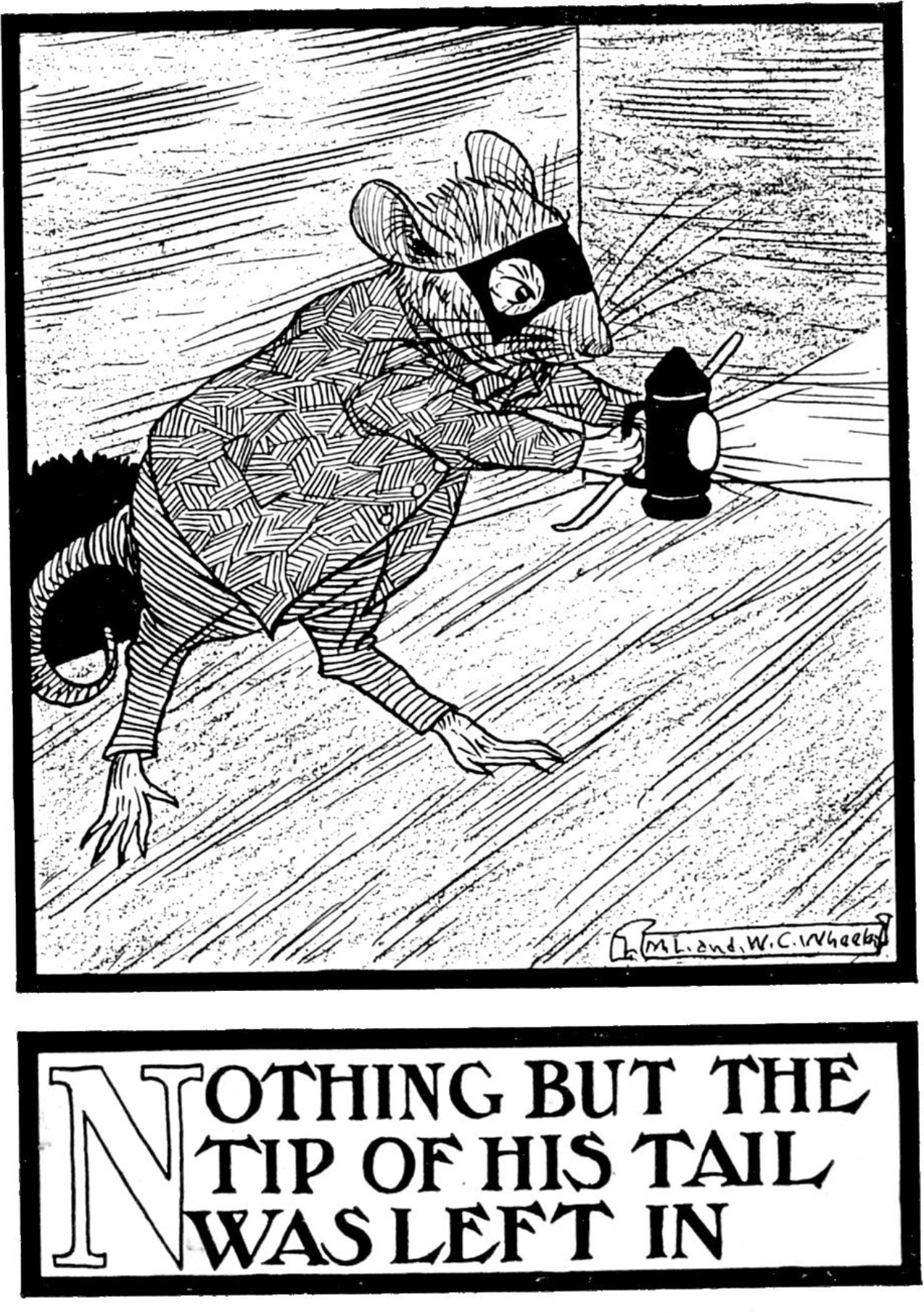

In F.M.H. (Florence M. Hill)’s 1915 children’s book The War of the Wooden Soldiers, illustrated by Marguerite Wheeler and Willard C. Wheeler, a masked mouse invades a child’s room and bites a chunk out of a wooden soldier — which leads the other soldiers and a puppy to seek revenge. (Part of the Dotty Dolly series.) The Wheelers also illustrated Lear’s Nonsense ABC’s. The timing of the publication makes me believe that this must be some sort of warning about a German invasion?

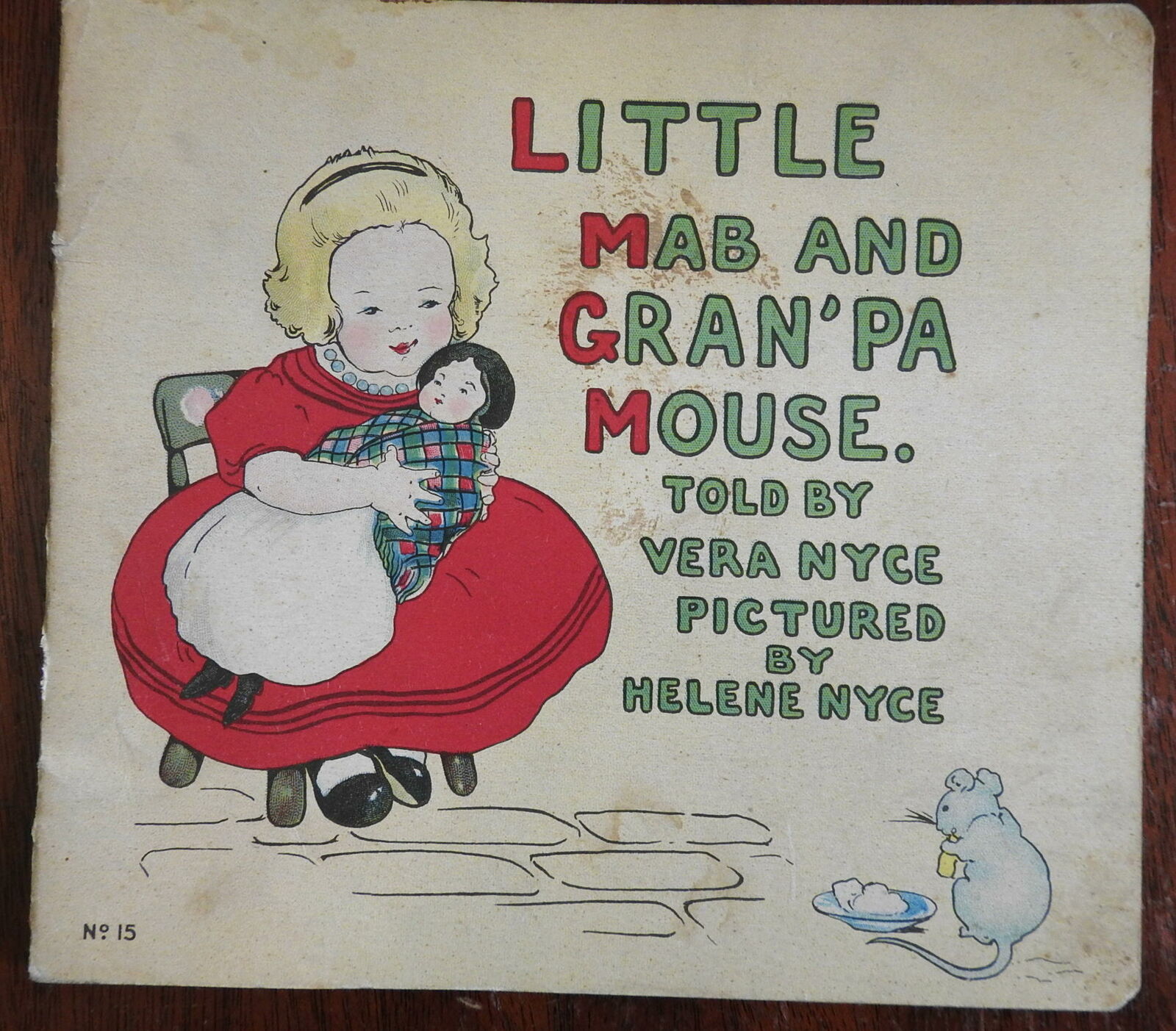

A strange 1916 children’s book — illustrated in an Art Nouveau style by Helene Nyce — about a very plump and dim-witted child who includes a mouse in her imaginative play. Nyce was a successful “commercial silhouette” illustrator at the time; she and her mother Vera also did children’s books.

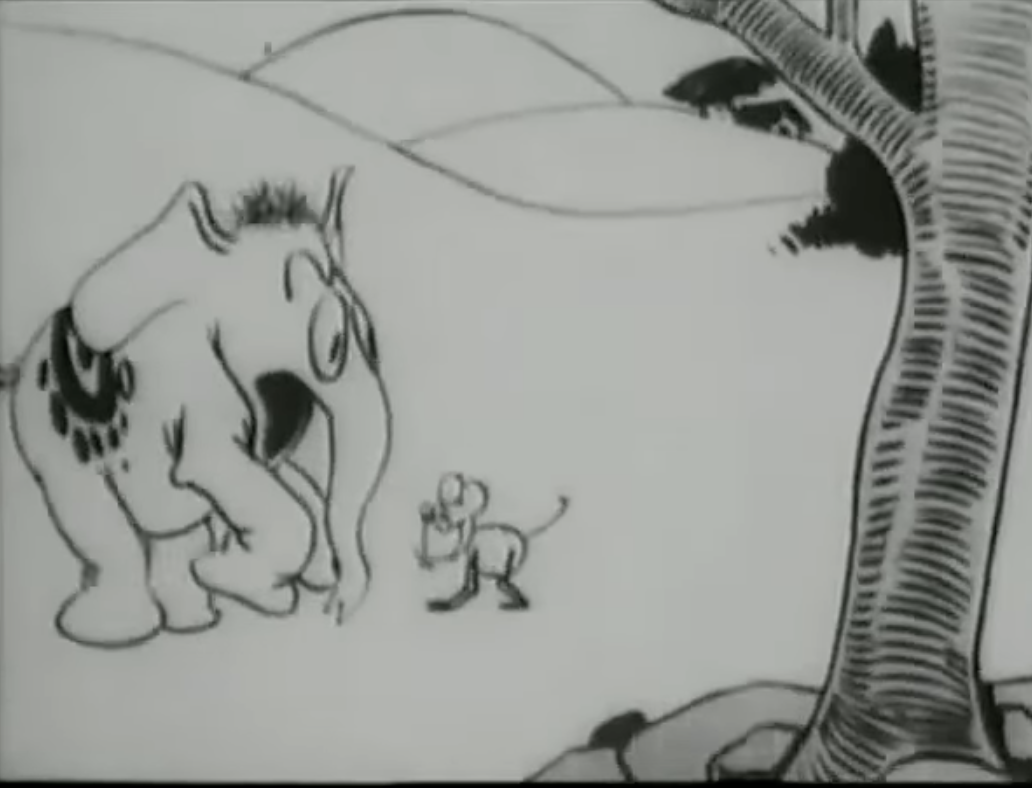

In George Herriman’s 1916 animated movie short Krazy Kat — Bugologist, Ignatz scares off a rogue elephant.

Otto Messmer’s 1919 animated short Feline Follies marks the first appearance of Messmer’s character Felix the Cat. Felix (at this point known as “Master Tom”) serenades a new love interest, and announces his intention to devote his nine lives to her. All the time he would have spent terrorizing the mouse population is instead spent primping in front of the mirror. It’s all fun and frolics until the mice destroy the house an oblivious Tom is supposed to be guarding, and the lady of the house throws him out by the tail. Now homeless, Felix goes to live with his love interest, only to find out she is the mother (and Felix is not the father) of a large litter of kittens. In reaction, Felix runs towards the local gasworks and commits suicide by intentionally inhaling coal gas. What the…?

Feline Follies was not the first short film by the Pat Sullivan Studio to feature a black cat as a protagonist. The studio’s first cat-themed animated film was The Tail of Thomas Kat (1917), currently a lost film. Black cats were also a recurring element in a film series by the Pat Sullivan Studio, the Charlie or Charley series — based on the screen persona of Charlie Chaplin. A black cat identical in design to Felix in Feline Follies had appeared in promotional materials for the animated short How Charlie Captured the Kaiser (August 1918). In other words, Felix seems to have evolved from these precursors.

In Felix Revolts (1923), upon finding that the city fathers consider cats a nuisance, Felix arranges a feline strike. When fish-stores are emptied by marauding cats and rodents take the town by storm, Felix and his brethren are given the recognition they deserve.

In George Herriman’s 1916 animated movie short Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing, Ignatz Mouse pelts Krazy Kat with bricks as Krazy Kat attempts to serenade Ignatz.

In Herriman’s 1916 animated movie short Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse at the Circus, Ignatz sneaks into the circus (even though Krazy bought Ignatz a half-ticket) and then scares a performer. There is some lascivious peeping and winking.

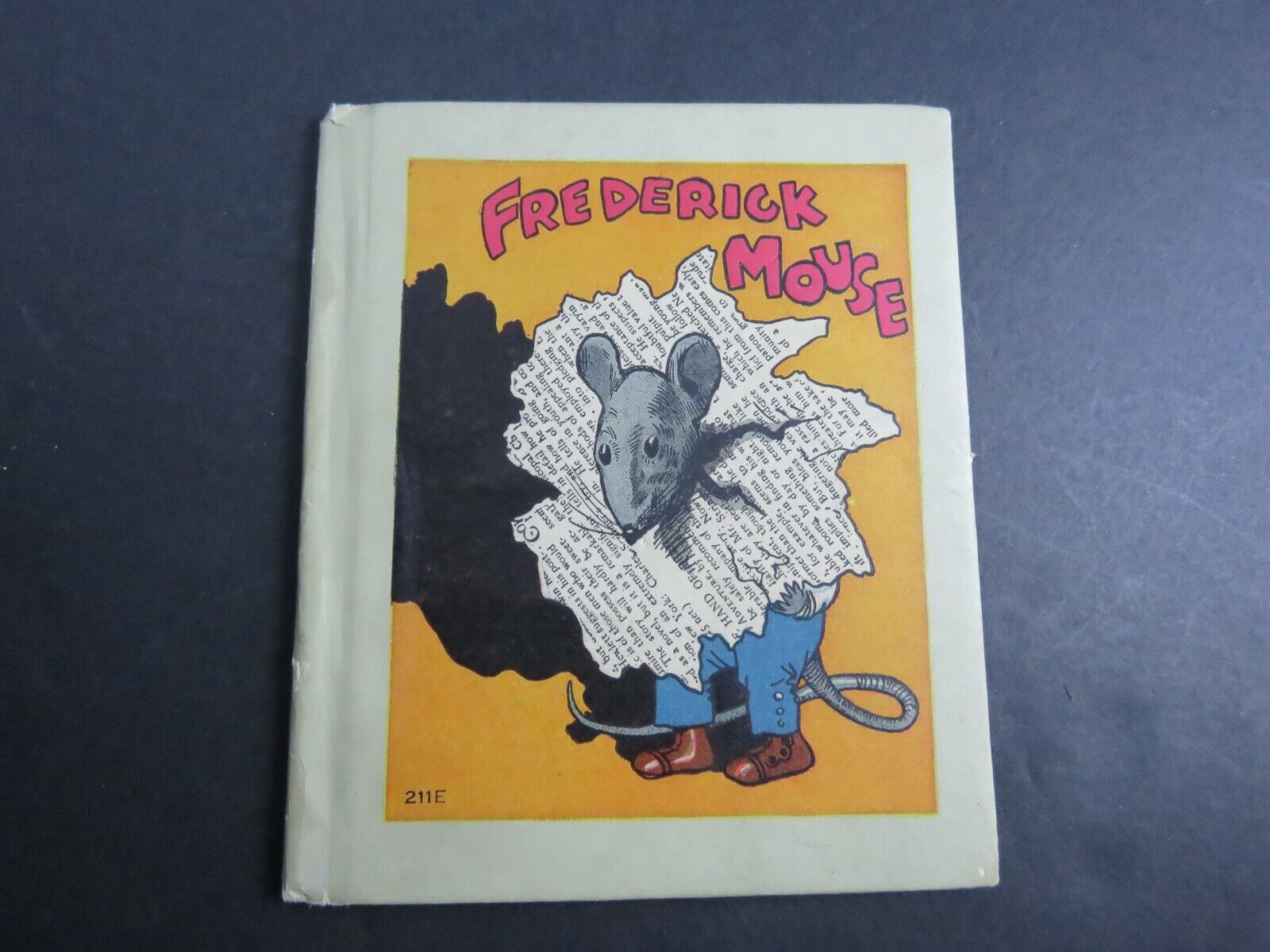

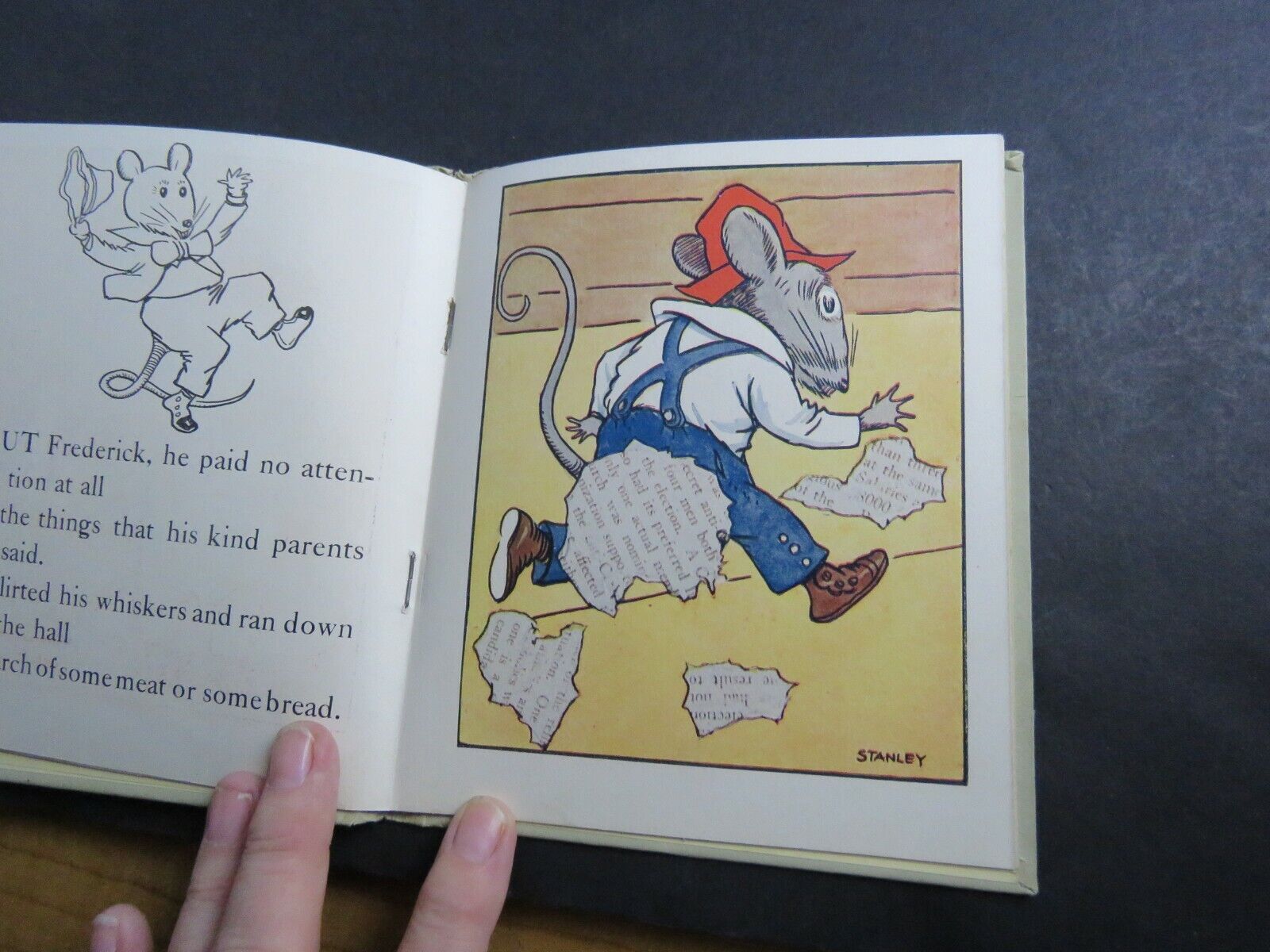

This 1917/1918 miniature book by Alice Crew Gall, illusrated by Lee Wright Stanley, seems to be quite rare. The same collaborators created Mother McGrew and Kate Kangaroo, Mother McGrew and Oliver Owl, Mother McGrew and Cordelia Clam (!), Pandora Pig, and Ringtail (about a raccoon). The illustrations are very funny; Stanley was an American cartoonist best known for his long-running (1923–1966) newspaper strip The Old Home Town.

The page shown here suggests that Frederick is a rebellious scamp. The torn-up printed page also suggests that what he is rebelling against are narrrative restraints; he is a picaresque figure, perhaps.

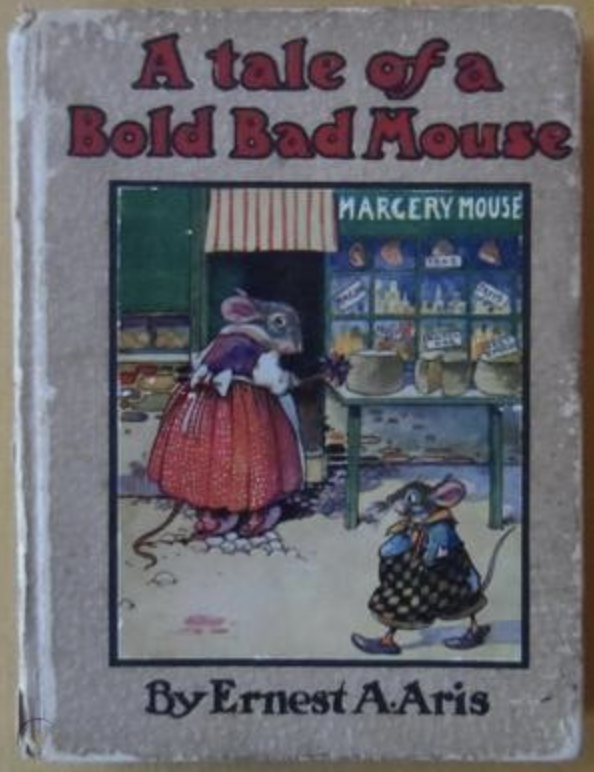

Ernest Aris, also known by the pen names Robin A Hood and Dan Crow, (1882–1963), was a prolific writer and illustrator who worked on hundreds of children’s books — as well as cigarette cards, postcards, toys and games. (He created Cococubs — a wildly popular set of hollowcast hand-painted lead figures of anthropomorphic creatures given away with Cadburys Bournville Cocoa from 1934 to 1939.)

He illustrated many mouse books. These include: Willie Mouse (1912), Wee Jenny Mouse (1912), A Tale of a Bold Bad Mouse (1916; an homage, perhaps, to Beatrix Potter’s 1904 The Tale of Two Bad Mice), That Little Grey Mouse (1916), Mother Mouse (1918), Little Mousey Muffet (1923). The anthropomorphic Willie Mouse was a recurring character, featured in Aris’s tales, Cococubs, cigarette cards, and board games. Also: Simon Fatty Mouse.

Perez the Mouse (1914), by Padre Luis Coloma (translated by Lady Moreton; illustrated by George Howard Vyse). El Ratoncito Pérez or Ratón Pérez is a folkloric figure of early childhood in Spain. In 1894, the Spanish writer, journalist and Jesuit Luis Coloma (1851–1915) wrote this story about Perez — whom he turned into a kind of tooth fairy figure — for eight-year-old King Alfonso XIII of Spain. The story details how he cunningly misleads any cats who may be lurking in the vicinity.

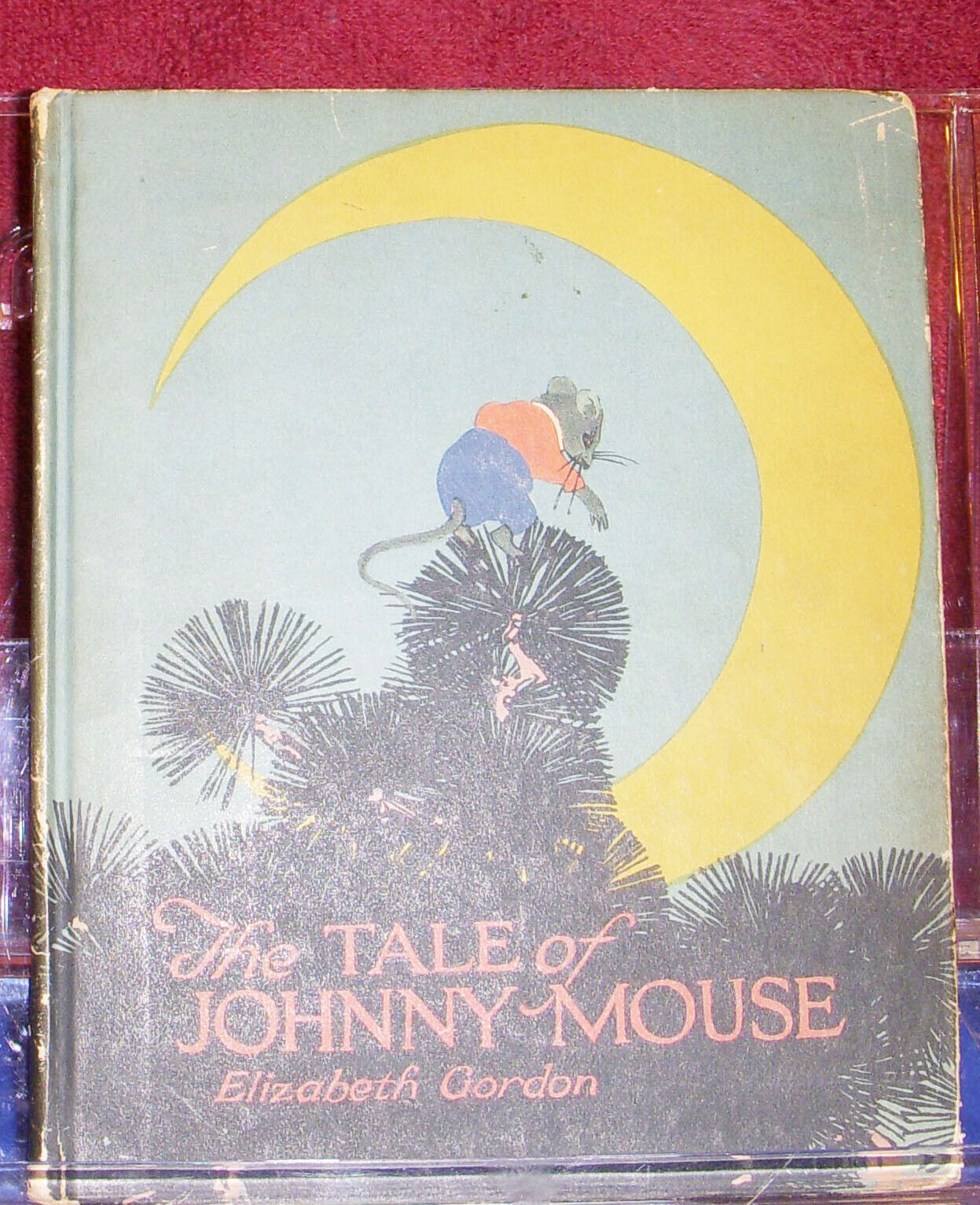

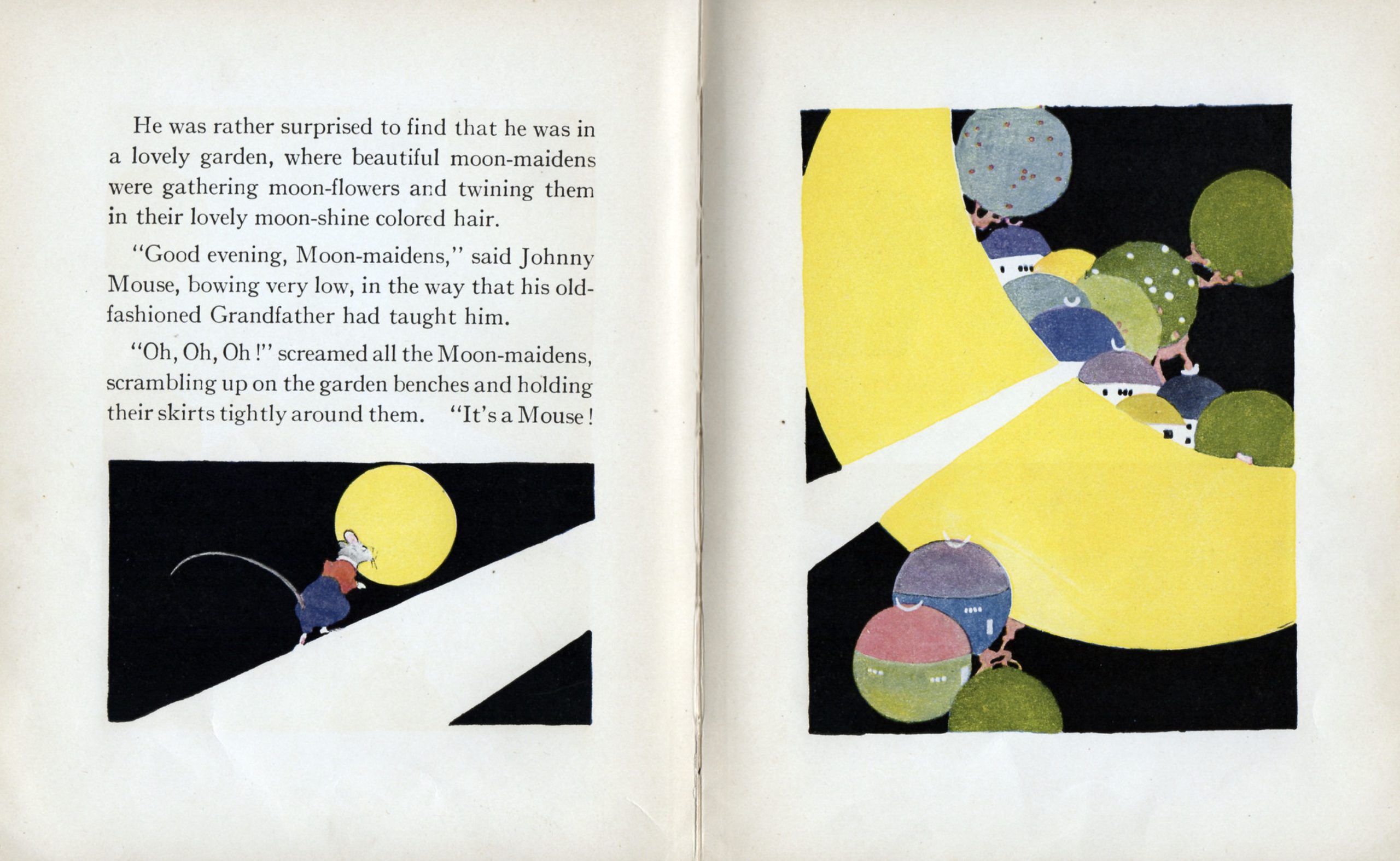

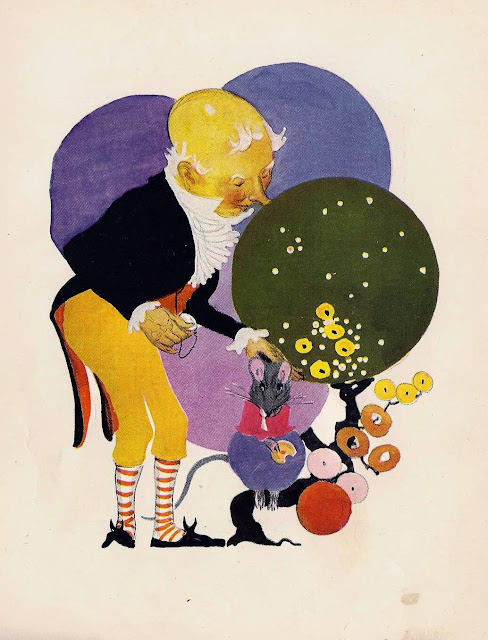

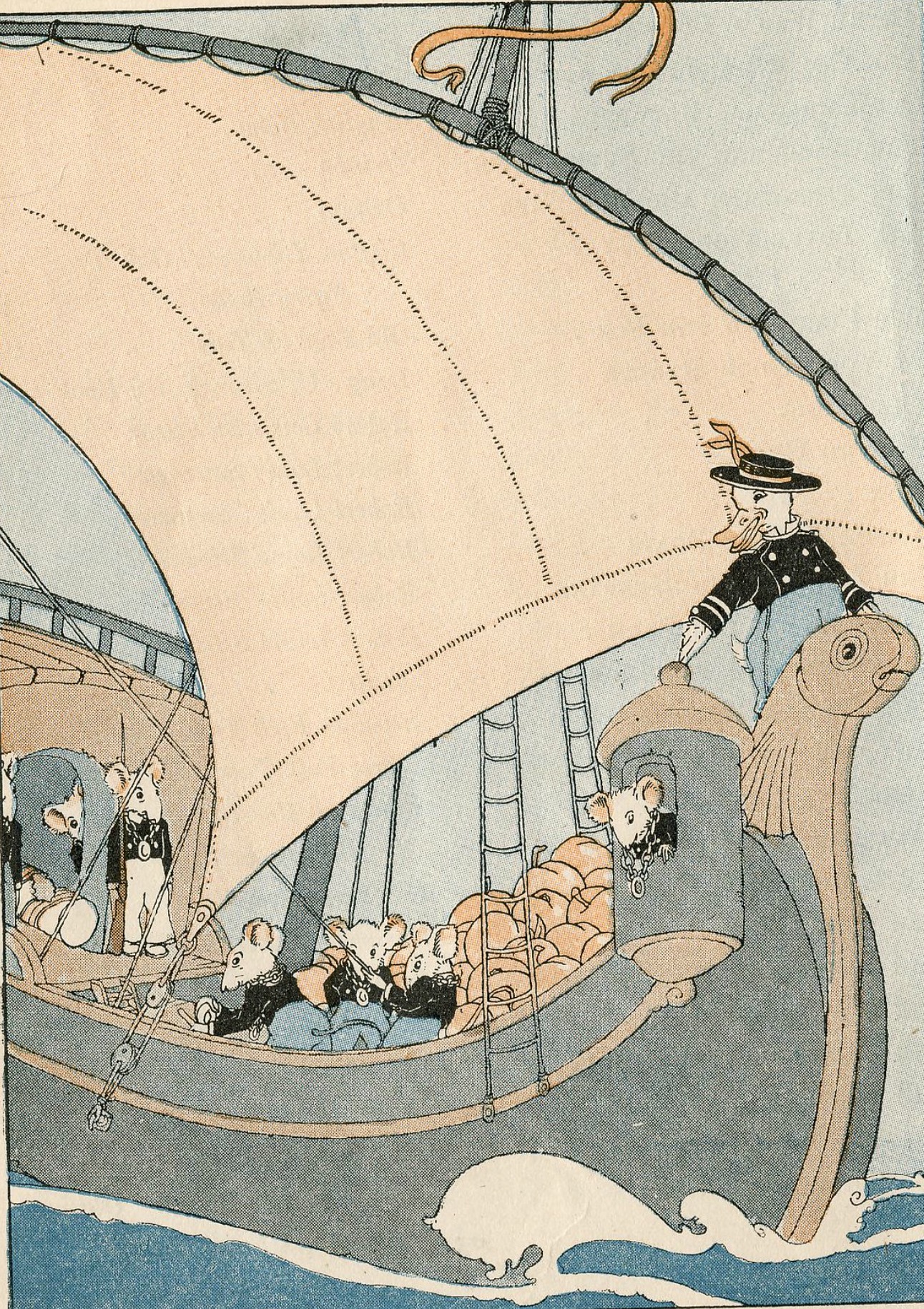

The Tale of Johnny Mouse (1920) is a collaboration between author Elizabeth Gordon and illustrator Maginel Wright Enright. Fun facts: She was the sister of architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and the mother of Elizabeth Enright, children’s book writer and illustrator. She illustrated 63 children’s books during her lifetime.

Johnny Mouse lives in the attic with his parents and grandparents and a large brood of sisters and brothers. When a mean cook with a cat moves in, Johnny travels to the moon to find cheese for his family. The man in the moon generously sends enough cheese sandwiches for them all and suggests Johnny plant a garden to provide for the future. Because the moral of the story is: It is best not to depend too much upon others.

Great illustration by Maud & Miska Petersham from Everyday Classics Second Read (1922). Is this where Donald Duck comes from?

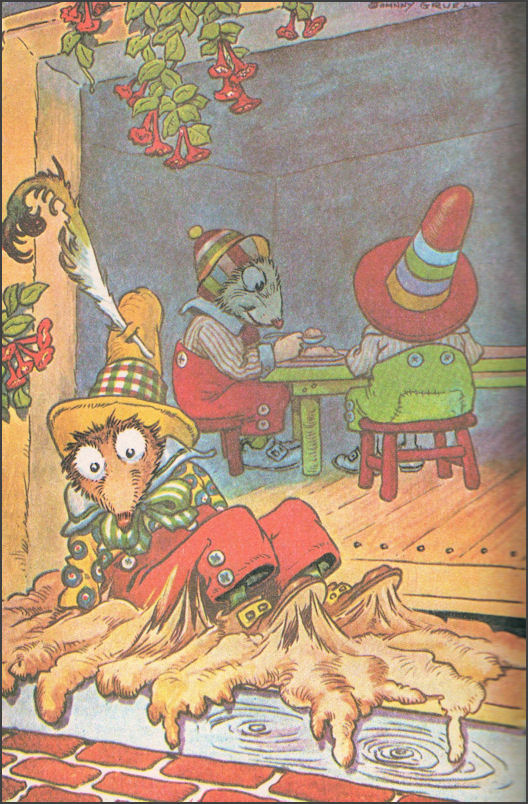

Johnny Mouse and the Wishing Stick, written and illustrated by Johnny Gruelle, belongs in the SCRAPPY SURVIVOR section of this post, I guess — but it’s also an adventure story.

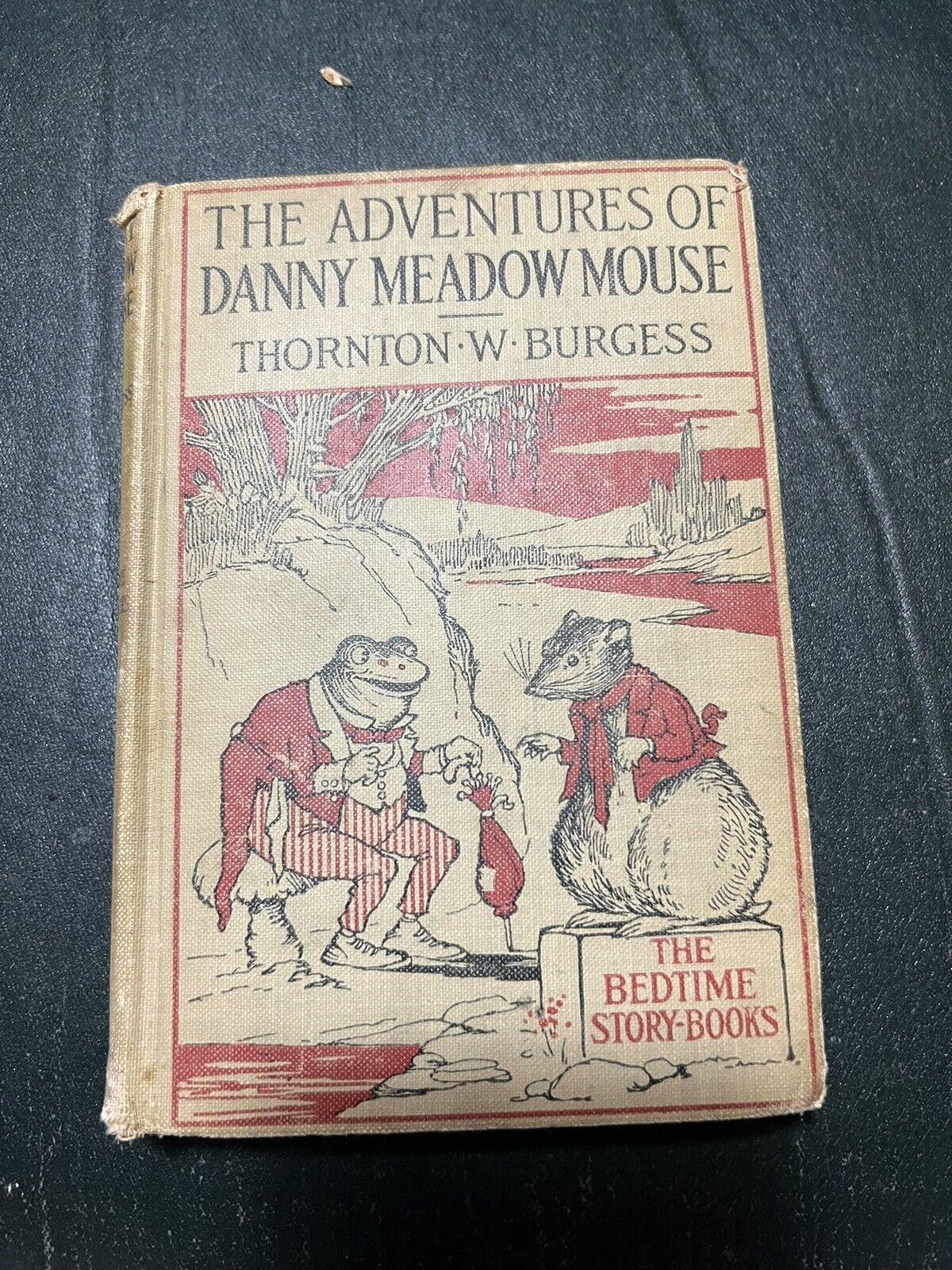

The Adventures of Danny Meadow Mouse, by Thornton W. Burgess (ill. Harrison Cady) concern a meadow mouse stalked by Reddy Fox and Hooty the Owl. He must use his wits to escape one snare and predator after another. His strange song: ““Isn’t any use to cry! / Not a bit! Not a bit! / Wipe your eyes and wipe ’em dry! / Use your wit! Use your wit! / Just remember that to-morrow / Never brings a single sorrow. / Yesterday has gone forever / And to-morrow gets here never. / Chase your worries all away; / Nothing’s worse than just to-day.”

Vera and Helene Nyce also collaborated on The Adventures of the Greyfur Family (1917).

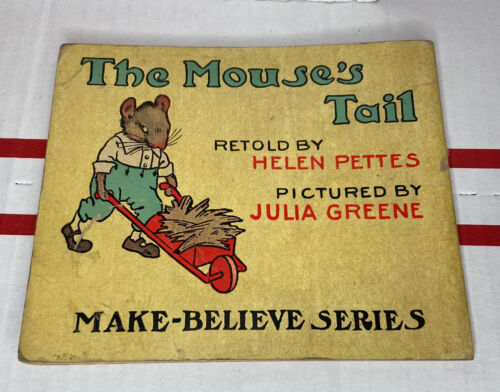

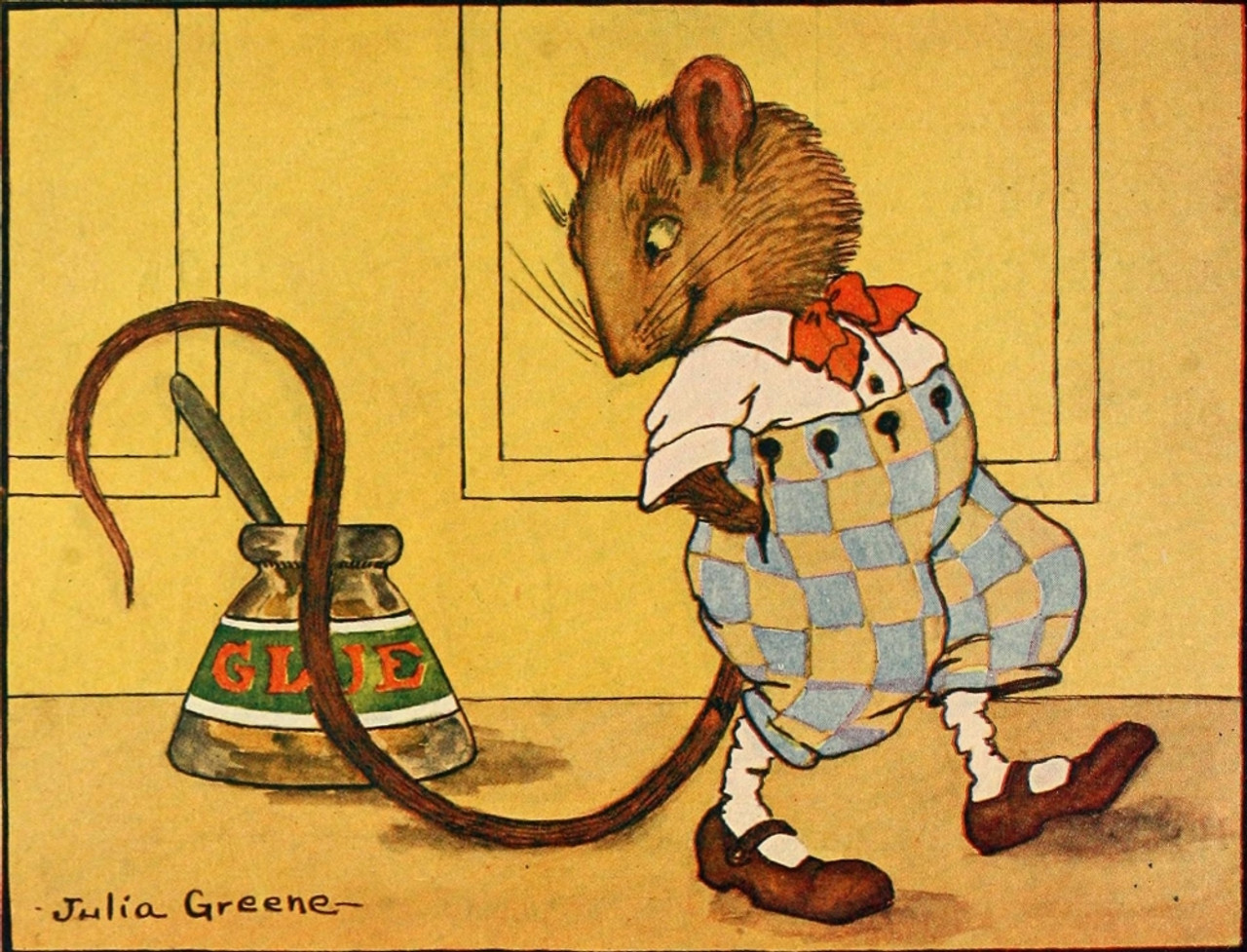

A 1917 retelling of a folk tale in which a mouse, in order to get his beautiful tail back from a cat, performs a series of tasks. The mouse’s vanity regarding his tail reminds me of C.S. Lewis’s Reepicheep. Illustrations by Julia Greene.

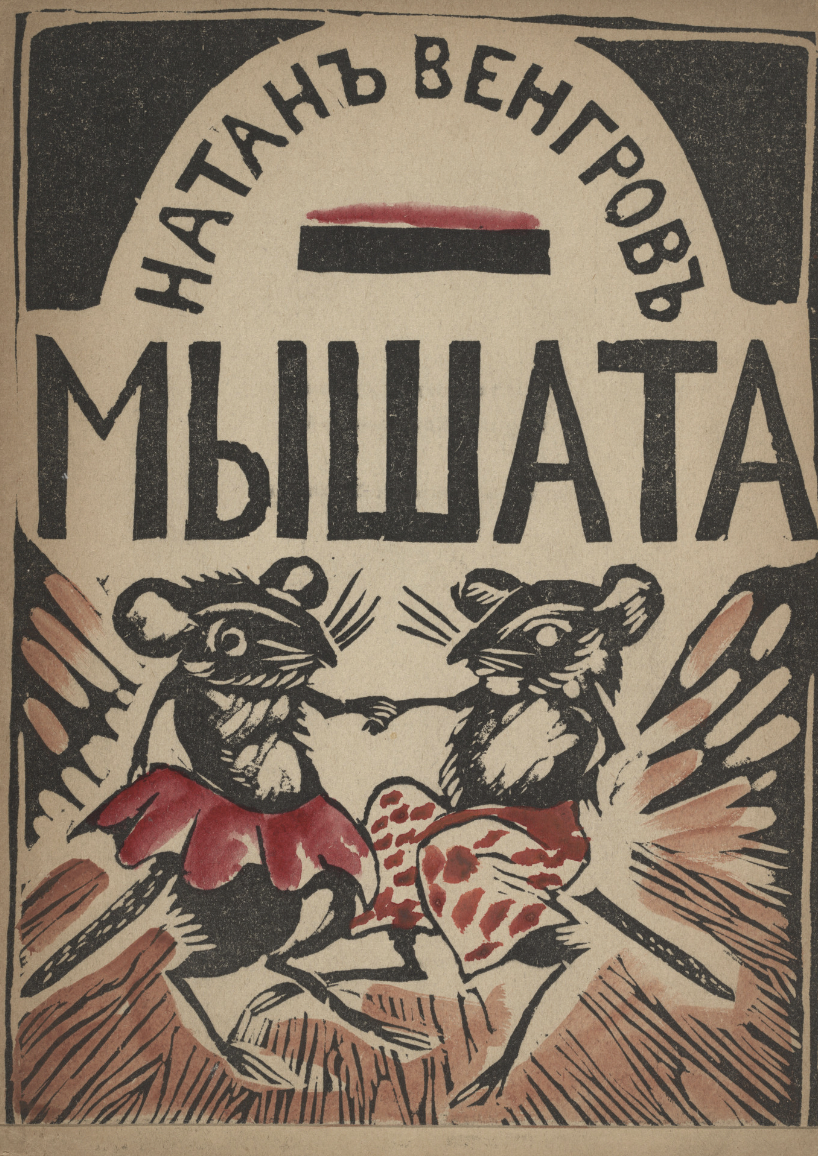

Myshata (Baby Mice) is a 1918 hand-crafted book with linoleum-block prints and watercolor additions. Poetry by Natan Vengrov, illustrations by Vera Mikhaĭlovna Yermolaeva. When everyone is asleep at night, little baby mice come out looking for food. They dance and eat hard biscuits (sukhari). In the end a cockroach comes out and finds their crumbs.

Myshata was issued by Vera Ermolaeva’s publishing collective, “Today” (Сегодня), which was the first significant group of Soviet artists to focus on children’s book design. They also pubished works by Sergei Esenin, Aleksei Remizov, and Evgeny Zamiatin. Yermolaeva was a significant figure in both children’s-book illustration and the artistic avant-garde; she was influenced by Suprematism, Cubism, and Futurism. The group disbanded in 1919 when Yermolaeva moved to Vitebsk, where she worked at the Institute of Practical Arts, alongside Marc Chagall and Kazimir Malevich. Yermolaeva became a director of the Institute, and also one of the founding members of the innovative artistic group UNOVIS. Tragically, Yermolaeva was arrested in 1934 and died in a Gulag labor-camp in 1937.

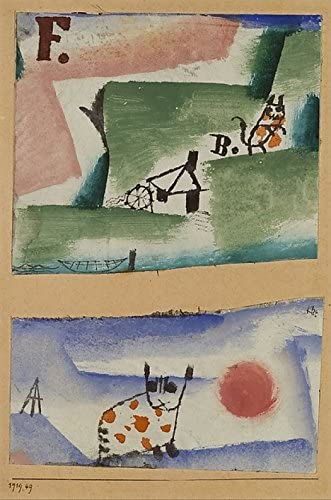

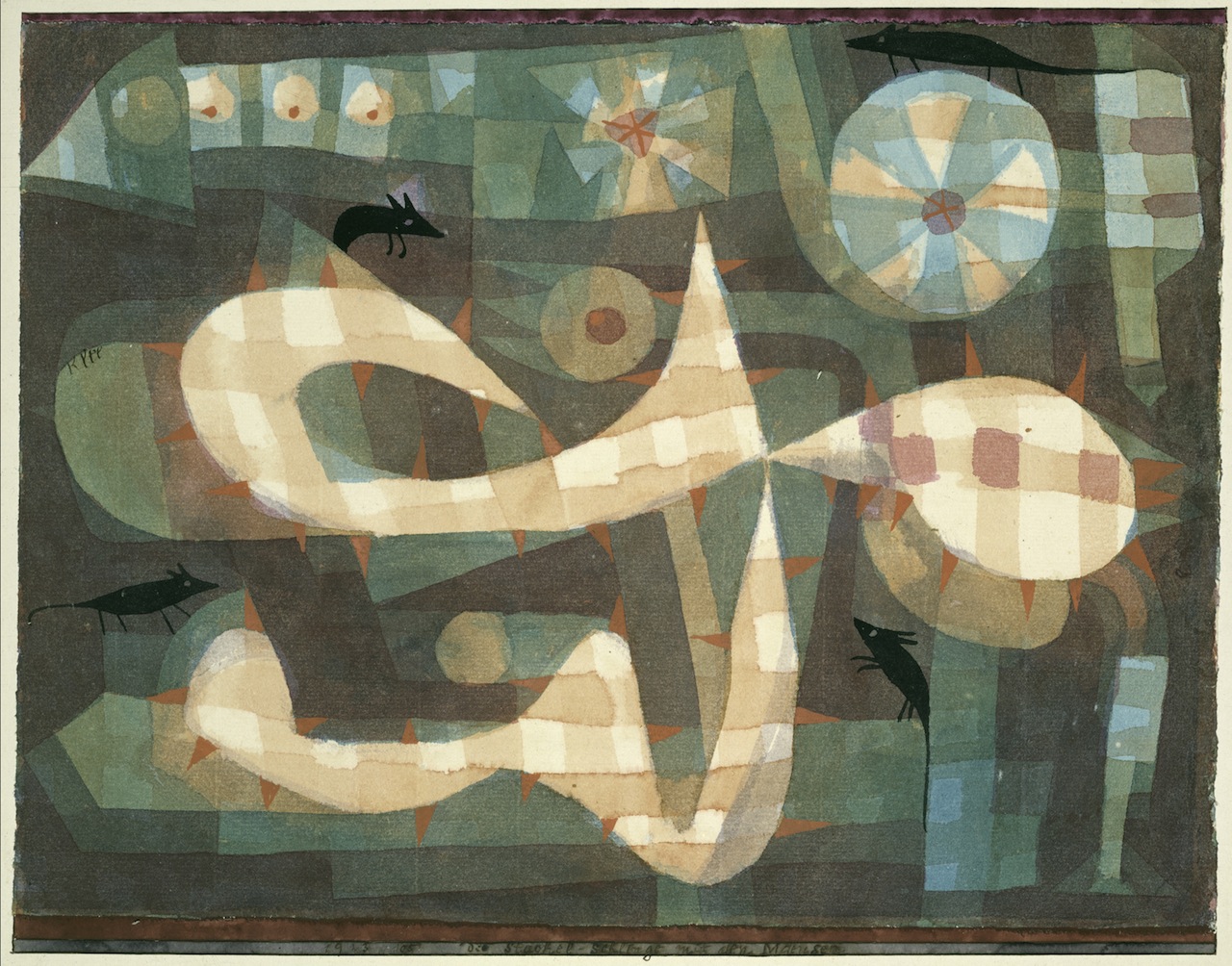

Tomcat’s Turf, a 1919 painting by Paul Klee, seems to show a scrappy survivor mouse defying a tomcat. Klee’s works reflect his dry humor and his sometimes childlike perspective. Foreshadowing Art Spiegelman’s Maus, perhaps? Klee would teach at the Düsseldorf Academy from 1931 to 1933, and was singled out by a Nazi newspaper, “Then that great fellow Klee comes onto the scene, already famed as a Bauhaus teacher in Dessau. He tells everyone he’s a thoroughbred Arab, but he’s a typical Galician Jew.” His home was searched by the Gestapo and he was fired from his job. The Klee family would emigrate to Switzerland in late 1933.

The above interpretation is troubled by the fact that the little figure in the upper part of the painting might be a cat, not a mouse — despite its small size and mouse-like posture. Most art critics describe the figure as a mouse, but in a 1992 book Marianne Vogel suggests that the “F” and “B” in this picture stand for Klee’s cats, Fripouille (Fripp) and Bobeli.

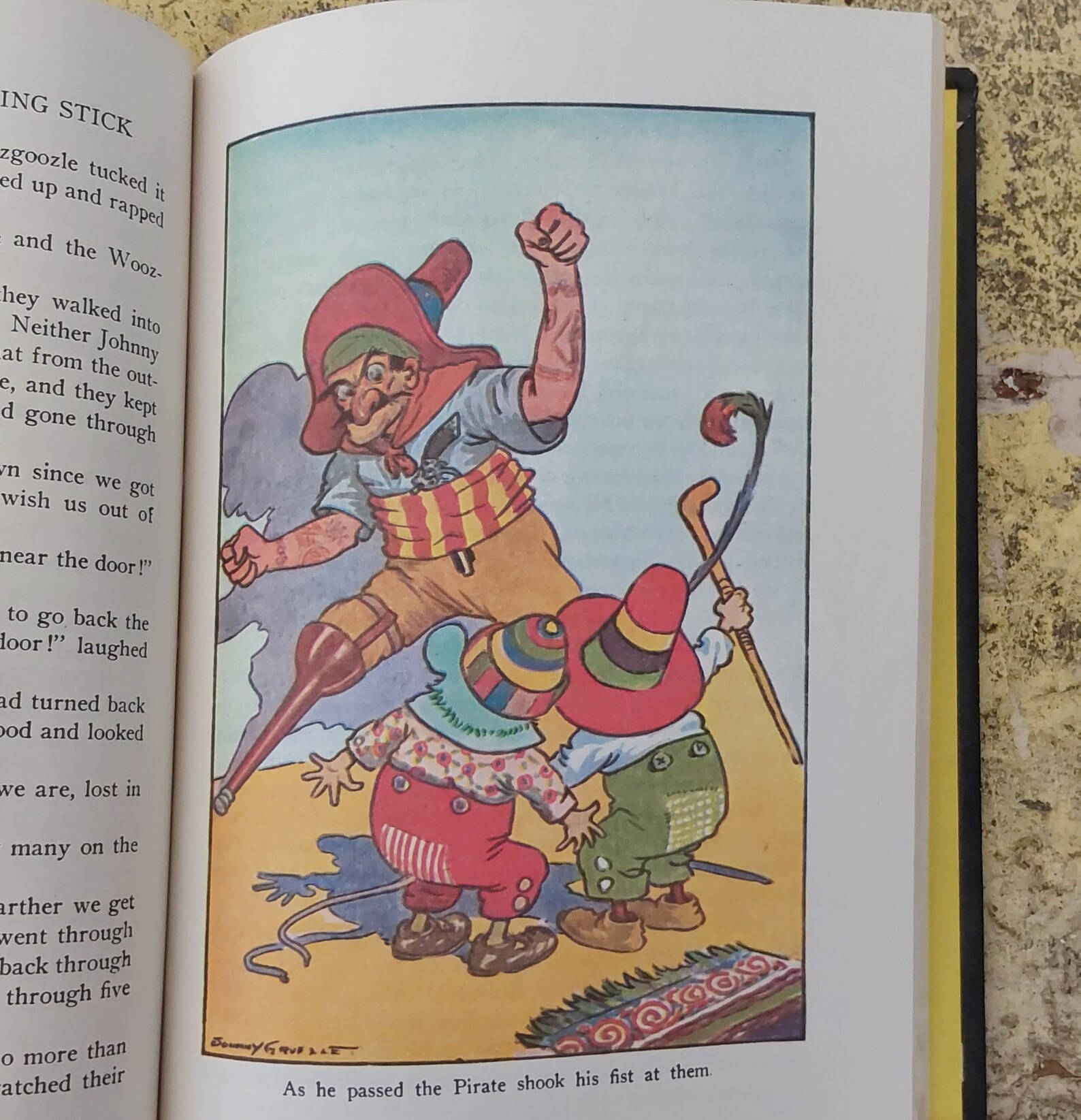

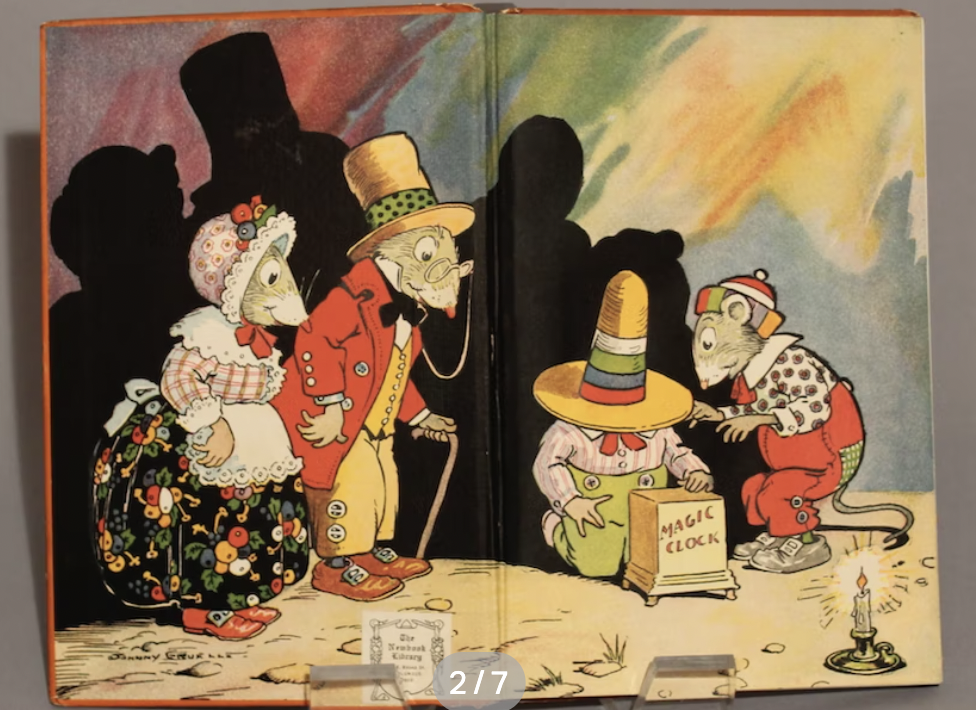

Johnny Mouse and the Wishing Stick is a strange and fantastical 1922 children’s book written and illustrated by Johnny Gruelle, political cartoonist, children’s book and comics author, and illustrator — best known as the creator of the massively popular Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy dolls. Gruelle’s work, which helped inspire Dr. Seuss, is great-looking: Animation historian Donald Crafton has described Gruelle’s illustrations as having a typically “clean, curvilinear style that looks ahead to the Disney graphics of the 1930s.”

Johnny and his grandparents live in a cigar box. When they go on a picnic, they encounter the Woozgoozle, a sombrero-headed creature who is always hungry — and who is forever stealing chickens from their town to eat. Johnny and his family persuade him to start eating sugared doughnuts instead. In the stories that follow, Johnny Mouse and the Woozgoozle will devour a tremendous amount of sweet treats: cream puffs, lollipops, ice cream sodas, ladyfingers, chocolate éclairs, taffy, pies, cakes, and especially pancakes. Whenever it seems as though Johnny may have to do a bit of hard work, they discover a magical object that permits them to instead spend their time eating more pancakes and ice cream sodas.

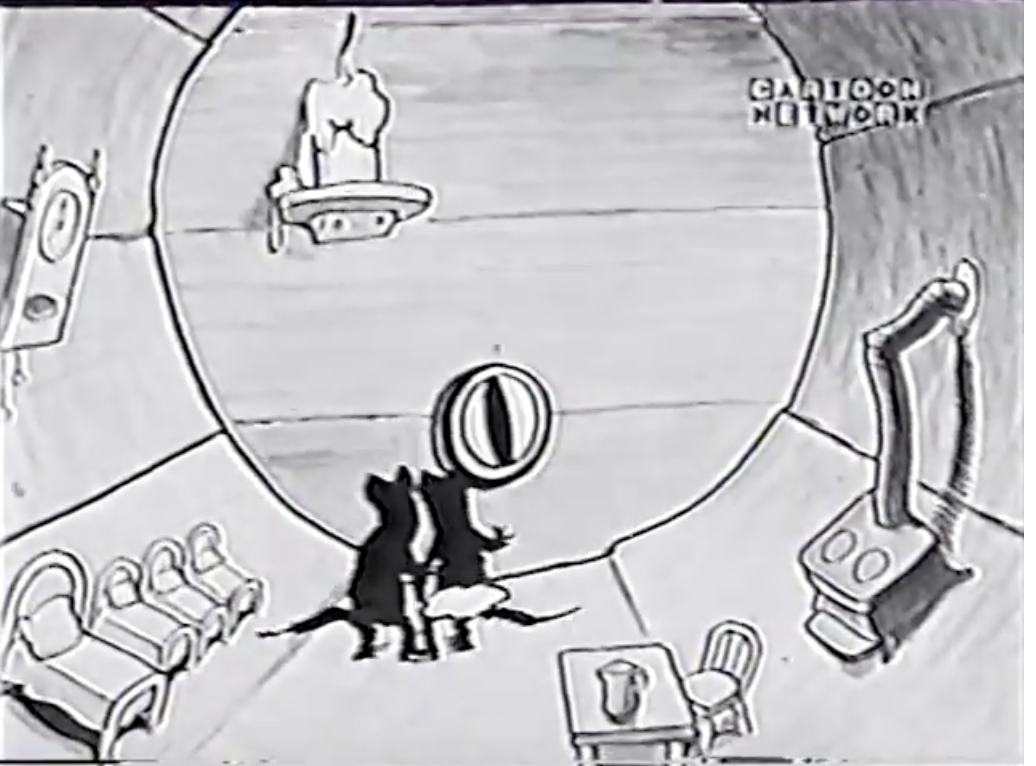

In cartoonist Paul Terry’s Cat and Mice, a 1921 Aesop’s Fables animated short, mice fed up with a cat’s depradations team up against it. Also see: RESOURCEFUL COLLABORATOR.

Note that in 1929 Terry would co-found Terrytoons, an American animation studio in New Rochelle, New York, that produced animated cartoons for theatrical release from 1929 to 1973. Terry, who managed to keep his studio profitable while others went out of business, was once quoted as saying, “Walt Disney is the Tiffany’s of the business, and I am the Woolworth’s.” That is to say: Like his mice, he was a scrappy survivor.

The 1922 Felix the Cat animated short Felix in the Swim begins with nice-cat Felix letting a mouse out of a mousetrap. In appreciation, the mouse offers to do Felix a favor — to help him sneak his friend out of the house so they can go swimming, despite the fact that the boy’s mother insists he stay home and practice the piano.

Paul Klee’s The Barbed Noose with the Mice (1923), watercolor and gouache on paper.

In Paul Terry’s 1920 animated short A Cat’s Life (Aesop’s Fables Studio), a cat has a mouse-slave. He forces the mouse to push him around in a car. He makes the mouse act as live bait to catch him a fish. He even uses the mouse as a tee when golfing. (The cat is a poor golfer and instead of hitting the ball, he beheads the mouse. Luckily, the mouse has replacement heads.) Later, Cupid hits the cat with his arrow. The cat proceeds to serenade a girl-cat on a balcony. The singing annoys Farmer Al Falfa, who takes the crescent moon hanging outside his window and throws it at the cat as if it were a boomerang. It hits him, but he is not fazed. The girl-cat falls off her balcony and onto the cat’s head. This annoys him, and he hits her with his lute. Later, the cat sees a group of mice doing physical exercise. He sets a trap for them: a board balanced on a rock. On one side of the board is a slice of cheese. One by one, the mice nibble at the cheese as the cat, standing on a rooftop, drops a brick on the other side of the board, which propels each mouse up to the cat, who grabs it and puts it in a box. However, one mouse frees the other mice…

… and takes revenge on the cat.

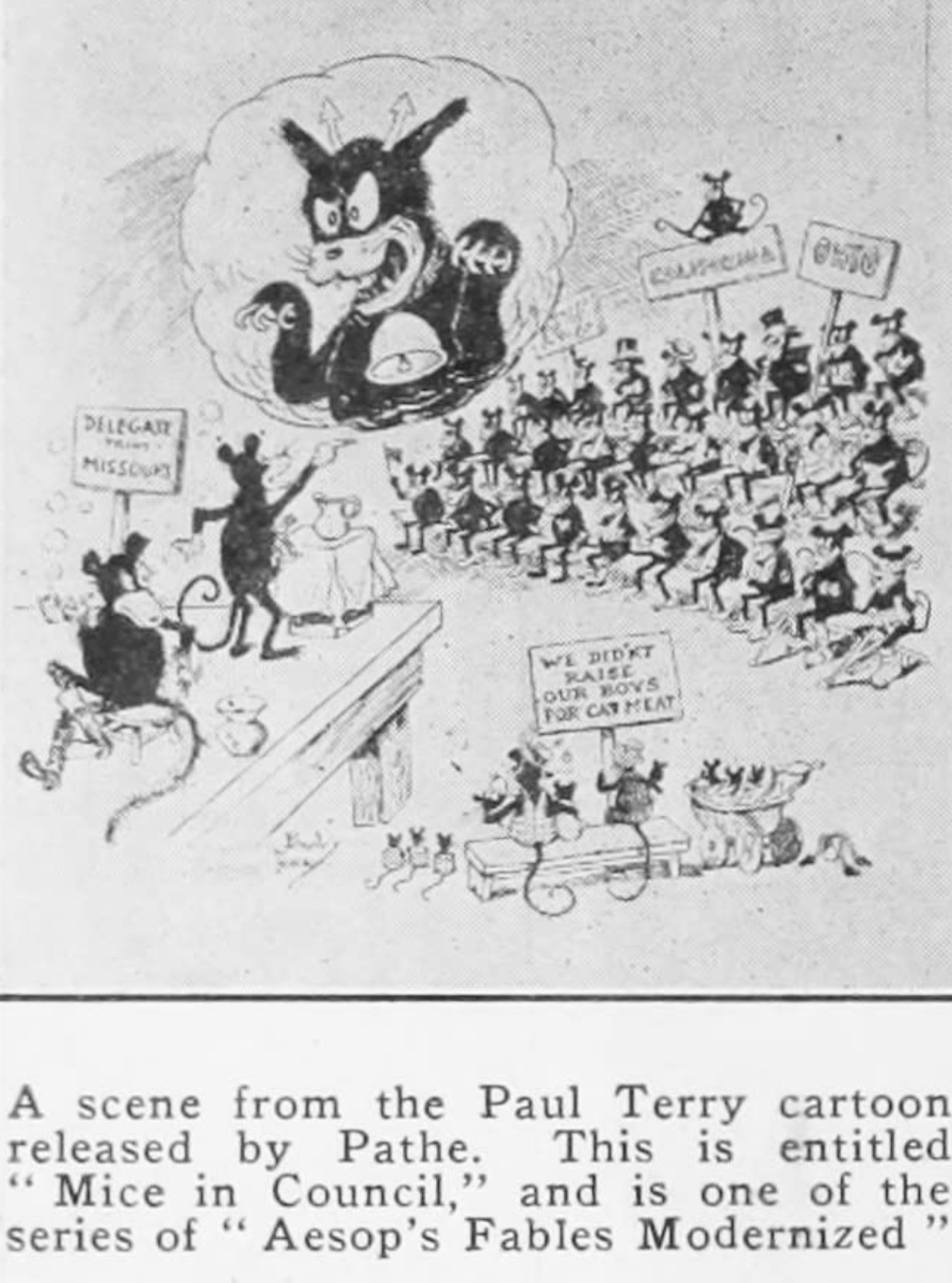

Terry directed a number of shorts for Aesop’s Fables Studio — see 1921 in particular for Mice in Council, The Country Mouse, Mice at War, Cat and Mice, etc.

In Terry’s Cat and Mice, a 1921 Aesop’s Fables animated short, mice fed up with a cat’s depradations team up against it. Also see: SCRAPPY SURVIVOR.

Mice at War, Mice in Council, and other 1921 Aesop’s Fables animated cartoon shorts by Paul Terry continue this theme of mouse as resourceful collaborator.

As noted in the MOUSE installment’s previous post, since at least the 19th century mice have been depicted as friends and steeds to fairies. Shown here is the 1922 book Grasshopper Green and the Meadow-Mice written and illustrated by John Rae.

Beatrix Potter’s 1918 children’s book The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse is her version of the country mouse / city mouse fable. (She herself had moved to the countryside around this time, which she much preferred to the city.) Although the book is named after Johnny Town-Mouse, our protagonist is Timmy Willie — a country bumpkin who accidentally winds up in the city, which he does not enjoy at all.

Arthur Scott Bailey was author of more than forty children’s books. The Tale of Dickie Deer Mouse (1918) involves a very gentle and polite field mouse constantly in search of a home where he won’t be attacked by predators. (He seems unable to make his own home, so he’s always on the lookout for someone else’s abandoned place.) In one chilling episode, two owls fight over the right to eat Dickie.

When Dickie finally does find a place to live, a horde of his distant relations descend upon him. They hibernate together for the winter, and then the peripatetic Dickie is off again in search of a new home.

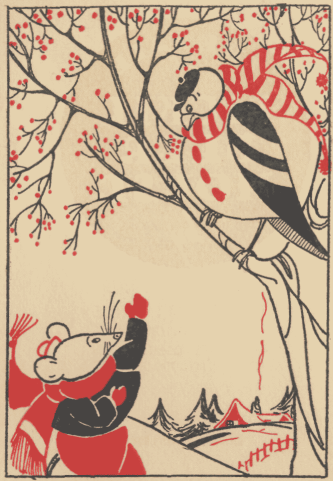

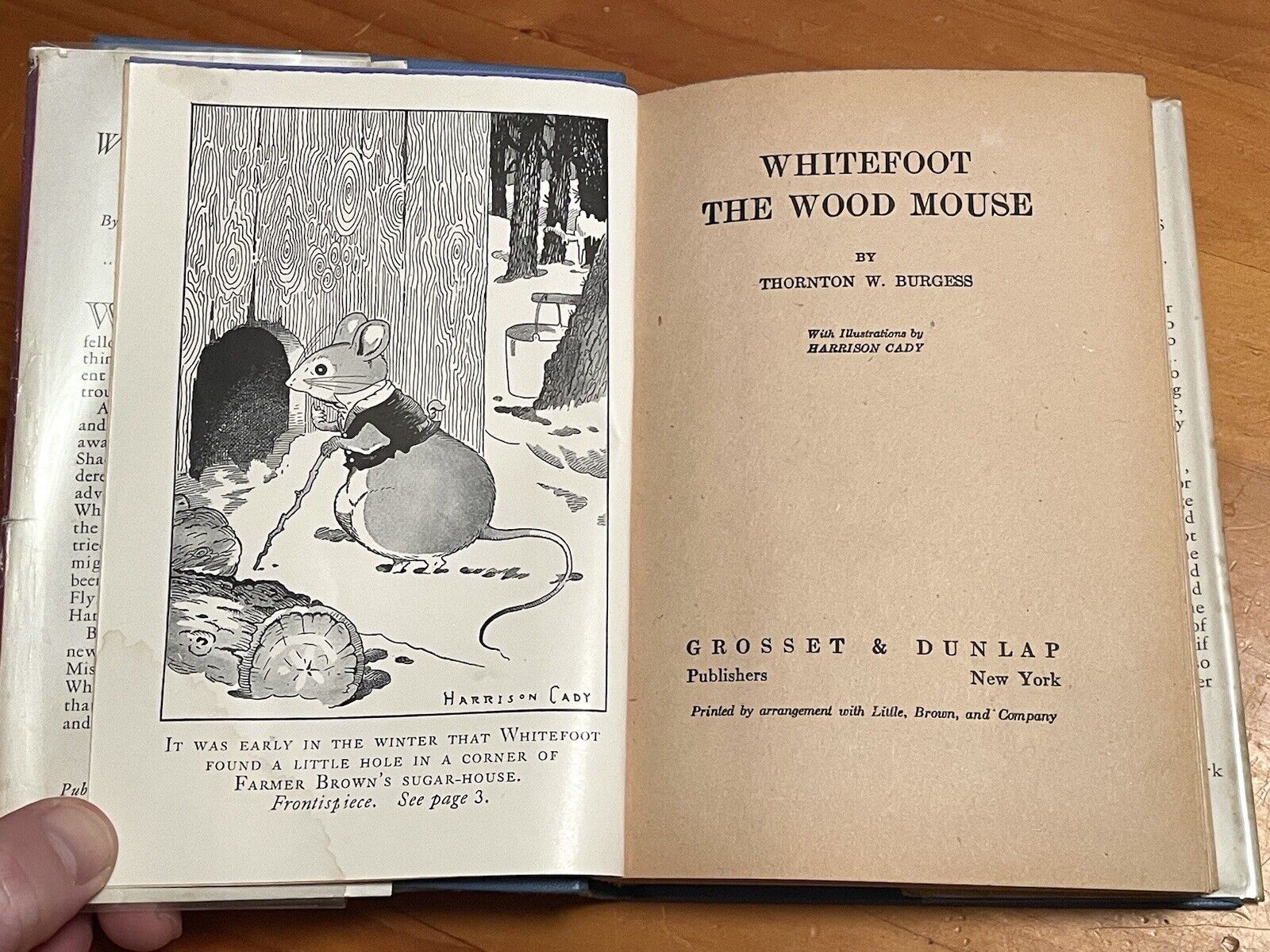

Thornton W. Burgess’s 1922 children’s book Whitefoot the Woodmouse has a similar plot to Arthur Scott Bailey’s The Tale of Dickie Deer Mouse. Whitefoot is constantly in search of a home.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.