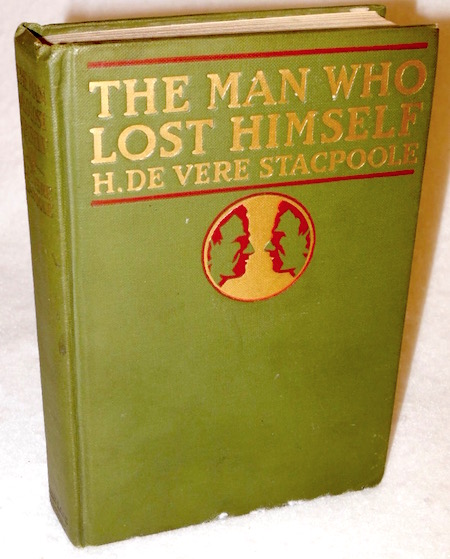

THE MAN WHO LOST HIMSELF (12)

By:

May 7, 2018

This year marks the 100th anniversary of a forgotten Avenger/Artful Dodger-type adventure novel, The Man Who Lost Himself. A man down on his luck wakes up after a drunken night in London only to discover… that he has somehow slipped into the identity of a wealthy aristocrat! HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this funny, thrilling yarn by H. De Vere Stacpoole — best known as author of The Blue Lagoon — here at HILOBROW.

When Jones found himself outside the office at last, and in the bustle of Fleet Street, he turned his steps west-wards.

He had almost forgotten the half formed determination to throw down his cards and get up from this strange game, which he had formed when Collins had asked him whether he would not have an interview with his wife. This coal mine business pushed everything else aside for the moment; the thought of that deal galvanized the whole business side of his nature, so that, as he would have said himself, bristles stood on it. A mine worth a million pounds, traded away for twenty-five thousand dollars!

He was taking the thing to heart, as though he himself had been tricked by Mulhausen, and now as he walked, a block in the traffic brought him back from his thoughts, and suddenly, a most appalling sensation came upon him. For a moment he had lost his identity. For a moment he was neither Rochester nor Jones, but just a void between these two. For a moment he could not tell which he was. For a moment he was neither. That was the terrible part of the feeling. It was due to over taxation of the brain in his extraordinary position, and to the intensive manner in which he had been playing the part of Rochester. It lasted perhaps, only a few seconds, for it is difficult to measure the duration of mental processes, and it passed as rapidly as it had come.

Seeing a bar he entered it, and a small glass of brandy closed the incident and made him forget it. He asked the way to Coutts’ Bank, which in 1692 was situated at the “Three Crowns” in the Strand, next door to the Globe Tavern, and which still holds the same position in the world of commerce, and nearly the same in the world of bricks and mortar.

He reached the door of the bank and was about to enter, when something checked him. It was the thought that he would have to endorse the cheque with Rochester’s signature.

He had copied it so often that he felt competent to make a fair imitation, but he had begun life in a bank and he knew the awful eye a bank has for a customer’s signature. His signature — at least Rochester’s — must be well known at Coutts’. It would never do to put himself under the microscope like that, besides, and this thought only came to him now, it might be just as well to have his money in some place unknown to others. Collins and all that terrible family knew that he was banking at Coutts’, events might arise when it would be very necessary too for him to be able to lay his hands on a secret store of money.

He had passed the National Provincial Bank in the Strand, the name sounded safe and he determined to go there.

He reached the bank, sent his name into the manager, and was at once admitted. The manager was a solid man, semi-bald, with side whiskers, and an air of old English business respectability delightful in these new and pushing days, he received the phantom of the Earl of Rochester with the respect due to their mutual positions.

Jones, between Coutts’ and the National Provincial, had done a lot of thinking. He foresaw that even if he were to give in a passable imitation of Rochester’s signature, all cheques signed in future would have to tally with that signature. Now a man’s handwriting, though varying, has a personality of its own, and he very much doubted as to whether he would be able to keep up that personality under the microscopic gaze of the bank people. He decided on a bold course. He would retain his own handwriting. It was improbable that the National Provincial had ever seen Rochester’s autograph; even if they had, it was not a criminal thing for a man to alter his style of writing. He endorsed the cheque Rochester, gave a sample of his signature, gave directions for a cheque book to be sent to him at Carlton House Terrace, and took his departure.

He had changed Rochester’s five pound note before going to Collins, and he had the change in his pocket, four pounds sixteen and sixpence. Five pounds, less the price of a cigar at the tobacconist’s where he had changed his note, the taxi to Sergeants’ Inn, and the glass of liqueur brandy. He remembered that he still owed for his luncheon yesterday at the Senior Conservative, and he determined to go and pay for it, and then lunch at some restaurant. Never again would he have luncheon at that Conservative Caravanserai, so he told himself.

With this purpose in mind, he was standing waiting to cross the road near Southampton Street, when a voice sounded in his ear and an arm took his.

“Hello, Rochy,” said the voice.

Jones turned, and found himself arm in arm with a youth of eighteen — so he seemed, a gilded youth, if there ever was a gilded youth, immaculately dressed, cheery, and with a frank face that was entirely pleasing.

“Hello,” said Jones.

“What became of you that night?” asked the cheery one, as they crossed the road still arm in arm.

“Which night?”

“Which night? Why the night they shot us out of the Rag Tag Club. Are you asleep, Rawjester — or what ails you?”

“Oh, I remember,” said Jones.

They had unlinked now, and walking along together they passed up Southampton Street and through Henrietta Street towards Leicester Square. The unknown doing all the talking, a task for which he seemed well qualified.

He talked of things, events, and people, absolutely unknown to his listener, of horses, and men, and women. He talked Jones into Bond Street, and Jones went shopping with him, assisting him in the choice of two dozen coloured socks at Beale and Inmans. Outside the hosier’s, the unknown was proposing luncheon, when a carriage, an open Victoria, going slowly on account of the traffic, drew Jones’ attention.

It was a very smart turn out, one horsed, but having two liveried servants on the box. A coachman, and a footman with powdered hair.

In the Victoria was seated one of the prettiest girls ever beheld by Jones. A lovely creature, dark, with deep, dreamy, vague blue-grey eyes — and a face! Ah, what pen could describe that face, so mobile, piquante, and filled with light and inexpressible charm.

She had caught Jones’ eye, she was gazing at him curiously, half mirthfully, half wrathfully, it seemed to him, and now to his amazement she made a little movement of the head, as if to say, “come here.” At the same moment she spoke to the coachman.

“Portman, stop please.”

Jones advanced, raising his hat.

“I just want to tell you,” said the Beauty, leaning a little forward, “that you are a silly old ass. Venetia has told me all — It’s nothing to me, but don’t do it — Portman, drive on.”

“Good Lord!” said Jones, as the vehicle passed on its way, bearing off its beautiful occupant, of whom nothing could now be seen but the lace covered back of a parasol.

He rejoined the unknown.

“Well,” said the latter, “what has your wife been saying to you?”

“My wife!” said Jones.

“Well, your late wife, though you ain’t divorced yet, are you?”

“No,” said Jones.

He uttered the word mechanically, scarcely knowing what he was saying.

That lovely creature his wife! Rochester’s wife!

“Get in,” said the unknown. He had called a taxi.

Jones got in.

Rochester’s wife! The contrast between her and Lady Plinlimon suddenly arose before him, together with the folly of Rochester seen gigantically and in a new light.

The taxi drew up in a street off Piccadilly; they got out; the unknown paid and led the way into a house, whose front door presented a modest brass door plate inscribed with the words:

They passed along a passage, and then down stairs to a large room, where small card tables were set out. An extraordinary room, for, occupying nearly half of one side of it stood a kitchen range, over which a cook was engaged broiling chops and kidneys, and all the other elements of a mixed grill. Old fashioned pictures of sporting celebrities hung on the walls, and opposite the range stood a dresser, laden with priceless old fashioned crockery ware. Off this room lay the dining room, and the whole place had an atmosphere of comfort and the days gone by when days were less laborious than our days, and comfort less allied to glitter and tinsel.

This was Carr’s Club.

The unknown sat down before the visitor’s book, and began to write his own name and the name of his guest.

Jones, looking over his shoulder, saw that his name was Spence, Patrick Spence. Sir Patrick Spence, for one of the attendants addressed him as Sir Patrick. A mixed grill, some cheese and draught beer in heavy pewter tankards, constituted the meal, during which the loquacious Spence kept up the conversation.

“I don’t want to poke my nose into your affairs,” said he, “but I can see there’s something worrying you; you’re not the same chap. Is it about the wife?”

“No,” said Jones, “it’s not that.”

“Well, I don’t want to dig into your confidences, and I don’t want to give you advice. If I did, I’d say make it up with her. You know very well, Rochy, you have led her the deuce of a dance. Your sister got me on about it the other night at the Vernons’. We had a long talk about you, Rochy, and we agreed you were the best of chaps, but too much given to gaiety and promiscuous larks. You should have heard me holding forth. But, joking apart, it’s time you and I settled down, old chap. You can’t put old heads on young shoulders, but our shoulders ain’t so young as they used to be, Rochy. And I want to tell you this, if you don’t hitch up again in harness, the other party will do a bolt. I’m dead serious. It’s not the thing to say to another man, but you and I haven’t any secrets between us, and we’ve always been pretty plain one to the other — well, this is what I want to say, and just take it as it’s meant. Maniloff is after her. You know that chap, the attaché at the Russian Embassy, chap like a billiard marker, always at the other end of a cigarette — other name’s Boris. Hasn’t a penny to bless himself with. I know he hasn’t, for I’ve made kind enquiries about him through Lewis, reason why — he wanted to buy one of my racers for export to Roosia. Seven hundred down and the balance in six months. Lewis served up his past to me on a charger. The chap’s rotten with debt, divorced from his wife, and a punter at Monte Carlo. That’s his real profession, and card playing. He’s a sleepy Slav, and if he was told his house was on fire he’d say, “nichévo,” meaning it don’t matter, it’s well insured — if he had a house to insure, which he hasn’t. But women like him, he’s that sort. But Heaven help the woman that marries him. He’d take her money and herself off to Monte, and when he’d broken her heart and spoiled her life and spent her coin, he’d leave her, and go off and be Russian attaché in Japan or somewhere. I know him. Don’t let her do it, Rochy.”

“But how am I to help it?” asked the perplexed Jones, who saw the meaning of the other. It did not matter in reality to him, whether a woman whom he had only seen once were to “bolt” with a Russian and find ruination at Monte Carlo, but this world is not entirely a world of reality, and he felt a surprisingly strong resentment at the idea of the girl in the Victoria “bolting” with a Russian.

It will be remembered that in Collins’ office, the lawyer’s talk about his “wife” had almost decided him to throw down his cards and quit. This shadowy wife, first mentioned by the bird woman, had, in fact, been the one vaguely felt insuperable obstacle in the way of his grand determination to make good where Rochester had failed, to fight Rochester’s battles, to be the Earl of Rochester permanently maybe, or, failing that, to retire and vanish back to the States with honourable pickings.

The sight of the real thing had, however, altered the whole position. Romance had suddenly touched Victor Jones; the gorgeous but sordid veils through which he had been pushing had split to some mystic wand, and had become the foliage of fairy land.

“I want to tell you — you are an old ass.”

Those words were surely enough to shatter any dream, to turn to pathos any situation. In Jones’ case they had acted as a most potent spell. He could still hear the voice, wrathful, but with a tinge of mirth in it, golden, individual, entrancing.

“How are you to help it?” said Spence. “Why, go and make up with her again, kick old Nichévo. Women like chaps that kick other chaps; they pretend they don’t, but they do. Either do that or take a gun and shoot her, she’d be better shot than with that fellow.”

He lit a cigarette and they passed into the card room, where Spence, looking at his watch, declared that he must be off to keep an appointment. They said good-bye in the street, and Jones returned to Carlton House Terrace.

He had plenty to think about.

The pile of letters waiting to be answered on the table in the smoking room reminded him that he had forgotten a most pressing necessity — a typist. He could sign letters all right, with a very good imitation of Rochester’s signature, but a holograph letter in the same hand was beyond him. Then a bright idea came to him, why not answer these letters with sixpenny telegrams, which he could hand in himself?

He found a sheaf of telegraph forms in the bureau, and sat down before the letters, dealing with them one by one, and as relevantly as he could. It was a rather interesting and amusing game, and when he had finished he felt fairly satisfied. “Awfully sorry can’t come,” was the reply to the dinner invitations. The letter signed “Childersley” worried him, till he looked up the name in Who’s Who and found a Lord answering to it at the same address as that on the note paper.

He had struck by accident on one of the alleviations of a major misery of civilized life, replying to Letters, and he felt like patenting it.

He left the house with the sheaf of telegrams, found the nearest post office — which is situated directly opposite to Charing Cross Station — and returned. Then lighting a cigar, he took the friendly and indefatigable Who’s Who upon his knee, and began to turn the pages indolently. It is a most interesting volume for an idle moment, full of scattered romance, tales of struggle and adventure, compressed into a few lines, peeps of history, and the epitaphs of still living men.

“I want to tell you — you are an old ass.”

The words still sounding in his ears made him turn again to the name Plinlimon. The contrast between Lady Plinlimon and the girl, whose vision dominated his mind, rose up again sharply at sight of the printed name.

Ass! That name did not apply to Rochester. To fit him with an appropriate pseudonym would be impossible. Fool, idiot, sumph — Jones tried them all on the image of the defunct, but they were too small.

“Plinlimon: 3rd Baron,” read Jones, “created 1831, Albert James, b. March 10th, 1862. O. S. of second Baron and Julia d. of J. H. Thompson of Clifton, m. Sapphira, d. of Marcus Mulhausen, educ. privately. Address The Roost, Tite Street, Chelsea.”

Mulhausen! He almost dropped the book. Mulhausen! Collins, his office, and that terrible family party all rose up before him. Here was the scamp who had diddled Rochester out of the coal mine, the father of the woman who had diddled him out of thousands. The paragraph in Who’s Who turned from printed matter to a nest of wriggling vipers. He threw the book on the table, rose up, and began to pace the floor.

The girl-wife in the Victoria, his own position — everything was forgotten, before the monstrous fact half guessed, half seen.

Rochester had been plucked right and left by these harpies. He had received five thousand pounds for land worth a million from the father, he had paid eight thousand, or a good part of eight thousand to the daughter. Fine business that!

I compared Jones, when he was fighting Voles, to a terrier. He had a good deal of the terrier in his composition, the honesty, the rooting out instinct, and the fury before vermin. Men run in animal groups, and if you study animals you will be surprised by nothing so much as the old race fury that breaks out in the most civilized animal before the old race quarry or enemy.

For a few seconds, as he paced the floor, Jones was in the mental condition of a dog in proximity to a hutched badger. Then he began to think clearly. The obvious fact before him was that Voles, the Plinlimons and Mulhausen were a gang; the presumptive fact was that the money paid in blackmail had gone back to Mulhausen, or at least a great part of it.

Was Mulhausen the spider of the web? Were all the rest his tools and implements?

Jones had a good deal of instinctive knowledge of women. He did not in his heart believe that a woman could be so utterly vile as to use love letters directed to her for the purpose of extracting money from the man who wrote them. Or rather that, whilst she might use them, it was improbable that she would invent the method. The whole business had the stamp of a mind masculine and utterly unscrupulous. Even at first he had glimpsed this vaguely, when he considered it probable that Lord Plinlimon had a hand in the affair.

“Now,” thought Jones, “if I could bring this home to Mulhausen, I could squeeze back that coal mine from him. I could sure.”

He sat down and lit another cigar to assist him in dealing with this problem.

It was very easy to say “squeeze Mulhausen,” it was a different thing to do it. He came to this conclusion after a few minutes’ earnest concentration of mind on that problematical person. Hitherto he had been dealing with small men and wasters. Voles was a plain scoundrel, quite easily overthrown by direct methods. But Marcus Mulhausen he guessed to be a big man. The first thing to be done was to verify this supposition. He rang the bell and sent for Mr. Church.

“Come in,” said he, when the latter appeared, “and shut the door. I want to ask you something.”

“Yes, my Lord.”

“It’s just this. I want you to tell me what you think of Lord Plinlimon, and what you have heard said about him. I have my own opinions — I want yours.”

“Well, my Lord,” began Church. “It’s not for me to say anything against his Lordship, but since you ask me I will say that it’s generally the opinion that his Lordship is a bit — soft.”

“Do you think he’s straight?”

“Yes, my Lord — that is to say —”

“Spit it out,” said Jones.

“Well, my Lord, he owes money, that’s well known; and I’ve heard it said a good deal of money has been lost at cards in his house, but not through his fault. Indeed, you yourself said something to me to that effect, my Lord.”

“Yes, so I did — But what I want to get at is this. Do you think he’s a man who would do a scoundrelly thing — that’s plain?”

“Oh, no, my Lord, he’s straight enough. It’s the other party.”

“Meaning his wife?”

“No, my Lord — her brother, Mr. Julian.”

“Ah!”

Church warmed a bit. “He’s always about there, lives with them mostly. You see, my Lord, he has no what you may call status of his own, but he manages to get known to people through her Ladyship.”

“Kind of sucker,” said Jones.

Mr. Church assented. The expression was new to him, but it seemed to apply.

Then Jones dismissed him.

The light was becoming clearer and clearer. Here was another member of the gang, another instrument of Marcus Mulhausen.

“To-morrow,” said Jones to himself, “I will go for these chaps. Voles is the key to the lot of them, and I have Voles completely under my thumb.”

Then he put the matter from his mind for a while, and fell to thinking of the girl — his wife — Rochester’s wife.

The strange thought came to him that she was a widow and did not know it.

He dined out that night, going to a little restaurant in Soho, and he returned to bed early, so as to be fresh for the business of the morrow.

He had looked himself up again in Who’s Who, and found that his wife’s name was Teresa. Teresa. The name pleased him vaguely, and now that he had captured it, it stuck like a burr in his mind. If he could only make good over the Mulhausen proposition, re-capture that mine, prove himself — would she, if he told her all — would she —?

He fell asleep murmuring the word Teresa.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.