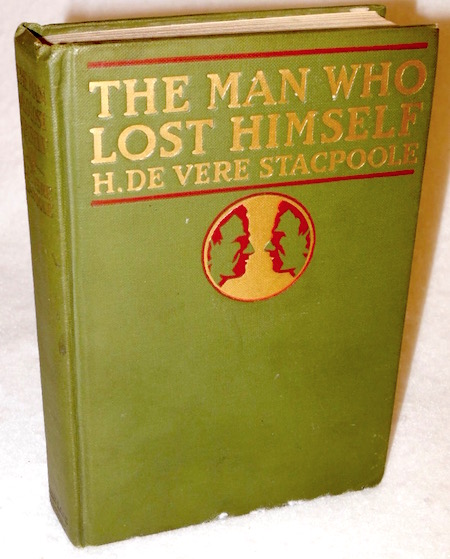

THE MAN WHO LOST HIMSELF (27)

By:

September 20, 2018

This year marks the 100th anniversary of a forgotten Avenger/Artful Dodger-type adventure novel, The Man Who Lost Himself. A man down on his luck wakes up after a drunken night in London only to discover… that he has somehow slipped into the identity of a wealthy aristocrat! HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this funny, thrilling yarn by H. De Vere Stacpoole — best known as author of The Blue Lagoon — here at HILOBROW.

The tobacco took the edge from his desire for food, increased his blood pressure, and gave rest to his mind.

He sat thinking. The story of Moths rose up before his mind and he fell to wondering how it ended and what became of the beautiful heroine with whom he had linked Teresa Countess of Rochester, of Zouroff with whom he had linked Maniloff, of Corréze with whom he had linked himself.

The colour of that story had tinctured all his sea-side experiences. Then Mrs. Henshaw rose up before his mind. What was she thinking of the lodger who had flashed through her life and vanished over the back garden wall? And the interview between her and Hoover — that would have been well worth seeing. Then the boy on the bicycle and the screaming invalid rose before him, and that mad rush down the slope to the esplanade; if those children with spades and buckets had not parted as they did, if a dog had got in his way, if the slope had ended in a curve! He amused himself with picturing these possibilities and their results; and then all at once a drowsiness more delightful than any dream closed on him and he fell asleep.

It was after dark when he awoke with the remnant of a moon lighting the field before him. From far away and borne on the wind from the sea came a faint sound as of a delirious donkey with brass lungs braying at the moon. It was the sound of a band. The Northbourne brass band playing in the Cliff Gardens above the moonlit sea. Jones felt to see that his cigarettes and matches were safe in his pocket, then he started, taking a line across country, trusting in Providence as a guide.

Sometimes he paused and rested on a gate, listening to the faint and indeterminate sounds of the night, through which came occasionally the barking of a distant dog like the beating of a trip hammer.

It was a perfect summer’s night, one of those rare nights that England alone can produce; there were glow worms in the hedges and a scent of new mown hay in the air. Though the music of the band had been blotted out by distance, listening intently he caught the faintest suspicion of a whisper, continuous, and evidently the sound of the sea.

An hour later, that is to say towards eleven o’clock, weary with finding his way out of fields into fields, into grassy lanes and around farm house buildings, desperate, and faint from hunger, Jones found a road and by the road a bungalow with a light in one of the windows.

A dauntingly respectable-looking bungalow in the midst of a well laid-out garden.

Jones opened the gate and came up the path. He was going to demand food, offer to pay for it if necessary, and produce gold as an evidence of good faith.

He came into the verandah, found the front door which was closed, struck a match, found the bell, pulled and pulled it. There was no response. He waited a little and then rang again, with a like result. Then he came to the lighted window.

It was a French window, only half closed, and a half turned lamp showed a comfortably furnished room and a table laid out for supper.

Two places were set. A cold fowl intact on a dish garnished with parsley stood side by side with a York ham the worse for wear, a salad, a roll of cowslip coloured butter, a loaf of home-made bread and a cheese tucked around with a snow-white napkin made up the rest of the eatables whilst a decanter of claret shone invitingly by the seat of the carver. There was nothing wanting, or only the invitation.

The fowl supplied that.

Jones pushed the window open and entered. Half closing it again, he took his seat at the table placing his hat on the floor beside him. Taking a sovereign from his pocket, he placed it on the white cloth. Then he fell to.

You can generally tell a man by his claret, and judging from this claret the unknown who had supplied the feast must have been a most estimable man.

A man of understanding and parts, a man not to be deluded by specious wine lists, a generous warmhearted and full-blooded soul — and here he was.

A step sounded on the verandah, the window was pushed open and a man of forty years or so, well-dressed, tall, thin, dark and saturnine stood before the feaster.

He showed no surprise. Removing his hat he bowed.

Jones half rose.

“Hello,” said he confusedly, with his mouth full—then he subsided into his chair.

“I must apologise for being late,” said the tall man, placing his hat on a chair, rubbing his long hands together and moving to the vacant seat. “I was unavoidably detained. But I’m glad you did not wait supper.”

He took his seat, spread his napkin on his knees, and poured himself out a glass of claret. His eyes were fixed on the sovereign lying upon the cloth. He had noted it from the first. Jones picked it up and put it in his pocket.

“That’s right,” said the unknown. Then as if in reply to a question: “I will have a wing, please.”

Jones cut a wing of the fowl, placed it in the extra plate which he had placed on one side of the table and presented it. The other cut himself some bread, helped himself to salad, salt and pepper and started eating, absolutely as though nothing unusual had occurred or was occurring.

For half a minute or so neither spoke. Then Jones said:

“Look here,” said he, “I want to make some explanations.”

“Explanations,” said the long man, “what about?”

Jones laughed.

“That sovereign which I put on the table and which I have put back in my pocket. I must apologise. Had I gone away before you returned that would have been left behind to show that your room had been entered neither by a hobo nor a burglar, nor by some cad who had committed an impertinence — perhaps you will believe that.”

The long man bowed.

“But,” went on Jones, “by a man who was driven by circumstances to seek hospitality without an invitation.”

The other had suddenly remembered the ham and had risen and was helping himself, his pince-nez which he wore on a ribbon and evidently only for reading purposes, dangling against his waistcoat-buttons.

“By circumstance,” said he, “that is interesting. Circumstance is the master dramatist — are you interested in the Drama?”

“Interested!” said Jones. “Why, I am a drama. I reckon I’m the biggest drama ever written, and that’s why I am here to-night.”

“Ah,” said the other, “this is becoming more interesting still or promising to become, for I warn you, plainly, that what may appear of intense interest to the individual is generally of little interest to the general. Now a man may, let’s say, commit some little act that the thing we call Justice disapproves of, and eluding Justice finds himself pressed by Circumstance into queer and dramatic positions, those positions though of momentary and intense interest to the man in question would be of the vaguest interest to the man in the stalls or the girls eating buns in the gallery, unless they were connected by that thread of — what shall we call it — that is the backbone of the thing we call Story.”

“Oh, Justice isn’t bothering after me,” said Jones — Then vague recollections began to stir in his mind, that long glabrous face, the set of that jaw, that forehead, that hair, brushed back.

“Why, you’re Mr. Kellerman, aren’t you?” said he.

The other bowed.

“Good heavens,” said Jones, “I ought to have known you. I’ve seen your picture often enough in the States, and your cinema plays — haven’t read your books, for I’m not a reading man — but I’ve been fair crazy over your cinema plays.”

Kellerman bowed.

“Help yourself to some cheese,” said he, “it’s good. I get it from Fortnum and Masons. When I stepped into this room and saw you here, for the first moment I was going to kick you out, then I thought I’d have some fun with you and freeze you out. So you’re American? You are welcome. But just tell me this. Why did you come in, and how?”

“I came in because I am being chased,” said Jones. “It’s not the law, I reckon I’m an honest citizen — in purpose, anyhow, and as to how I came in I wanted a crust of bread and rang at your hall door.”

“Servants don’t sleep here,” said Kellerman. “Cook snores, bungalow like a fiddle for conveying sounds, come here for sleep and rest. They sleep at a cottage down the road.”

“So?” said Jones. “Well, getting no reply I looked in at the window, saw the supper, and came in.”

“That’s just the sort of thing that might occur in a photo play,” said Kellerman. “When I saw you, as I stepped in, sitting quietly at supper the situation struck me at once.”

“You call that a situation,” said Jones. “It’s bald to some of the situations I have been in for the last God knows how long.”

“You interest me,” said Kellerman, helping himself to cheese. “You talk with such entire conviction of the value of your goods.”

“How do you mean the value of my goods?”

“Your situations, if you like the term better. Don’t you know that good situations are rarer than diamonds and more valuable? Have you ever read Pickwick?”

“Yep.”

“Then you can guess what I mean. Situations don’t occur in real life, they have to be dug for in the diamond fields of the mind and —”

“Situations don’t occur in real life!” said Jones. “Don’t they — now, see here, I’ve had supper with you and in return for your hospitality I’ll tell you every thing that’s happened to me if you’ll hear it. I guess I’ll shatter your illusions. I’ll give you a sample: I belong to the London Senior Conservative Club and yet I don’t. I have the swellest house in London yet it doesn’t belong to me. I’m worth one million and eight thousand pounds, yet the other day I had to steal a few sovereigns, but the law could not touch me for stealing them. I have an uncle who is a duke yet I am no relation to him. Sounds crazy, doesn’t it, all the same it’s fact. I don’t mind telling you the whole thing if you care to hear it. I won’t give you the right names because there’s a woman in the case, but I bet I’ll lift your hair.”

Kellerman did not seem elated.

“I don’t mind listening to your story,” said he, “on one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“That you will not be offended if I switch you off if the thing palls and hand you your hat, for I must tell you that though I came down here to get sleep, I do most of my sleeping between two in the morning and noon. I work at night and I had intended working to-night.”

“Oh, you can switch me off when you like,” said Jones.

Supper being finished, Kellerman fastened the window, and, carrying the lamp, led the way to a comfortably furnished study. Here he produced cigars and put a little kettle on a spirit stove to make tea.

Then, sitting opposite to his host, in a comfortable armchair, Jones began his story.

He had told his infernal story so often that one might have fancied it a painful effort, even to begin. It was not. He had now an audience in touch with him. He suppressed names, or rather altered them, substituting Manchester for Rochester and Birdwood for Birdbrook. The audience did not care, it recked nothing of titles, it wanted Story — and it got it.

At about one o’clock the recital was interrupted whilst tea was made, at two o’clock or a little after the tale finished.

“Well?” said Jones.

Kellerman was leaning back in his chair with eyes half closed, he seemed calculating something in his head.

“D’ you believe me?”

Kellerman opened his eyes.

“Of course I believe you. If you had invented all that you would be clever enough to know what your invention is worth and not hand it out to a stranger. But I doubt whether anyone else will believe you — however, that is your affair — you have given me five reels of the finest stuff, or at least the material for it, and if I ever care to use it I will fix you up a contract giving you twenty-five per cent royalties. But there’s one thing you haven’t given me — the dénouement. I’m more than interested in that. I’m not thinking of money, I’m a film actor at heart and I want to help in the play. Say, may I help?”

“How?”

“Come along with you to the end, give all the assistance in my power — or even without that just watch the show. I want to see the last act for I’m blessed if I can imagine it.”

“I’d rather not,” said Jones. “You might get to know the real names of the people I’m dealing with, and as there is a woman in the business I don’t feel I ought to give her name away even to you. No. I reckon I’ll pull through alone, but if you’d give me a sofa to sleep on to-night I’d be grateful. Then I can get away in the morning.”

Kellerman did not press the point.

“I’ll give you better than a sofa,” he said. “There’s a spare bed, and you’d better not start in the morning; give them time to cool down. Then towards evening you can make a dash. The servants here are all right, they’ll think you are a friend run down from town to see me. I’ll arrange all that.”

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.