10 Best Adventures of 1995

By:

September 1, 2020

Twenty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures from the Nineties (1994–2003) were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Neal Stephenson‘s sci-fi adventure The Diamond Age: Or, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. When the designer of the Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer: a Propædeutic Enchiridion — an interactive story-telling device intended to inculcate in the granddaughter of “Equity Lord” Alexander Chung-Sik Finkle-McGraw the knowledge and skills to subvert the dominant paradigm — bootlegs a copy for his own daughter, it instead falls into the hands of young Nell, a bright 4-year-old slum-dweller. Under the tutelage of the Primer, Nell not only survives but thrives. Lord Finkle-McGraw, meanwhile, attempts to exploit Hackworth to advance the goals of his tribe; so does Dr. X, the Chinese engineer (and powerful Confucian leader) who’d helped Hackworth create the illicit Primer. Meanwhile, the actress Miranda, who provides the voice of the Primer and becomes a kind of surrogate mother to Nell, seeks the child out. All of this takes place against the backdrop of a Neo-Victorian British colonial society in which nanotechnology has made it possible for anyone to 3-D print food and objects, and government has become obsolete. The relationship between Nell and her Primer is an affecting one; in a sense, this is a book is a bildungsroman about homo superior — like Stapledon’s Last Men in London or Odd John, say, or Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder. However, in the book’s second half, the plot goes off the rails — with the introduction of tribes such as the Drummers, who create a subconscious hive mind through sexual orgies (is this a reference to Alan Moore’s Halo Jones comic?); the powerful CryptNet organization; and the Chinese Fists of Righteous Harmony. Stephenson’s goal is to explore the unintended consequences of a post-scarcity world… but the story ends abruptly and inconclusively. Fun facts: An enchiridion is a handbook; a propædeutic is a preliminary teaching, for beginners. Other fun fictional propædeutic enchiridions include Owen Hughes’s Arithmetic, Grammar, Botany & these Pleasing Sciences made Familiar to the Capacities of Youth, in Joan Aiken’s The Whispering Mountain (1968); and Huey, Dewey and Louie’s Junior Woodchucks’ Guidebook, from Carl Barks’s Donald Duck comics; the Junior Woodchucks first appear in 1951. PS: When my friends Elizabeth Foy Larsen and Tony Leone and I pitched the family activity book UNBORED to Bloomsbury, in 2010, we explicitly compared it to Stephenson’s Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer.

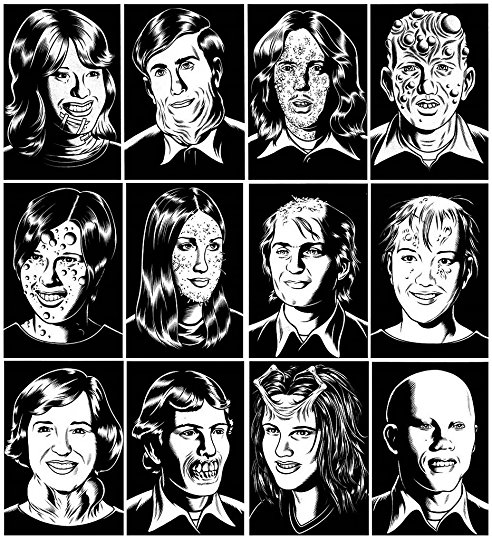

- Charles Burns‘s horror/sci-fi graphic novel Black Hole (serialized 1995–2005; in book form, 2005). I became aware of Charles Burns in the mid-1980s, thanks to his retro-sci-fi/horror “El Borbah” and “Big Baby” stories, which at the level of form may have paid tribute to the stylings of Will Elder, Hergé, and Chester Gould — but which were more sophisticated, in a surrealist, absurdist way. I was 28 when Kitchen Sink (Fantagraphics took over, later) began publishing the twelve installments that would make up Black Hole; I was 38 by the time the complete version was published. I mention this because my take on the story changed, during those years. A sexually transmitted disease mutates teenagers — over the course of a summer, in a suburb of Seattle, in the mid-1970s — into B-movie-esque monsters! The lucky ones are those who merely grow a little tail, or sprout chest-tendrils, or who shed their skin! Within this milieu, a lover’s triangle develops among Chris, Rob, and Keith; Keith, meanwhile, falls under the erotic spell of Eliza, a free-spirited artist living with dope dealers! Chris runs away, to live in the woods near her fellow freaks; but someone is killing them! When early issues of Black Hole appeared, I reveled in what I understood to be Burns’s nihilistic, body-horror take on, say, Dazed and Confused. However, by the time the last installment appeared, I looked forward not to finding out what happened next (for better or worse, it’s essentially a midcentury-style romance comic) so much as reimmersing myself in Burns’s fully realized world — gorgeous chiaroscuro, discontinuous chronology, teenage angst, sexual frustration and liberation… plus David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs. Wow! Fun facts: “There are certain truths that exist in genre fiction, even though it’s full of stereotypes and two-dimensional characters,” Burns said in an interview, once. “There’s a certain amount of unconsciousness that goes into genre fiction or genre movies. And out of that unconsciousness, I always see a certain kind of truth.”

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure Our Game. Tim Cranmer, an independently wealthy ex-Treasury boffin, has retired to his Somerset manor house and vineyard with his beautiful young lover, Emma. One evening, he is visited by police officers investigating the disappearance of Larry Pettifer, a professor at Bath University. Pettifer, we discover, had once been a British intelligence operative… and Cranmer was his handler and friend (frenemy, really) for twenty years. Pettifer and Emma had grown close, it seems, and Emma has also taken a powder. What’s more, Pettifer — a bohemian who’s never cared about money — has absconded with a large sum of money skimmed from British intelligence ops. Did the missing couple run away together? Or might Cramner have murdered his former protégé and romantic rival? Once Cramner uses his Cold War-honed skills to figure out what’s really happened, and bodies start turning up, the chase is on! Like Call for the Dead (1961), le Carré’s first novel, this one is both an espionage thriller and a murder mystery. In fact, I picture Cranmer as being much like James Mason’s character in The Deadly Affair, Sidney Lumet’s 1967 adaptation of Call for the Dead.…. Fun facts: The novel’s title refers to Winchester College football (known as Winkies, WinCoFo, or “Our Game”); Cranmer and Pettifer were Winchester schoolmates.

- Nicola Griffith’s sci-fi adventure Slow River. When we first meet Lore, the protagonist and sometime narrator of Slow River, she’s naked, injured, dumped to die by a kidnapper — whose true motivation we’ll only learn at the end. She’s taken in by Spanner, a charismatic female hacker and con artist; the two become lovers and co-conspirators, though eventually Spanner turns out to be not only untrustworthy but manipulative and amoral. Through flashbacks, we learn that Lore is the youngest child of the wealthy and powerful van Oest family — whose engineered bacteria provide clean drinking water in an age where untreated water is no longer potable. (We also learn that there’s a twisted secret at the heart of Lore’s family, one she only slowly figures out.) There are a few sci-fi gadgets — everyone has a personal ID chip inserted into their hand; everyone accesses the Internet via a “tablet” — but the technology of greatest import here is biotech, specifically related to drinking water. Like Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang, this story is a day in the life — many days in the life — of a talented but lowly worker, in a future industry. Although there are a few tense action scenes, it’s primarily a Robinsonade: We’re watching a smart, talented person solve problems. It’s also about overcoming privilege, and recovering from trauama. For some readers, this is boring stuff — “almost like a manual on water purification at times,” “her super power is being prodigiously good at sewage treatment management” — but I remained riveted. Fun facts: Winner of the Nebula Award for Best Novel, as well as the Lambda Literary Award — which is awarded annually to books which explore LGBT themes. Griffith also won a Lambda for her first novel, Ammonite (1993); since Slow River, four more of her books have also won a Lambda Award.

- José Saramago’s sardonic Robinsonade Ensaio sobre a cegueira (published in English as: Blindness). In this powerfully written anti-Cozy Catastrophe, when an unnamed city is plagued with an epidemic of “white blindness,” the afflicted are confined within an abandoned mental hospital to prevent them infecting others. One woman, known as “the doctor’s wife,” is spared from the blindness; we follow her efforts to protect her husband and their makeshift family — a boy with no mother, a girl with dark glasses, a dog — from the ruthless (though blind) mob which quickly assumes control over the hospital’s inmates. In doing so, our protagonist mustn’t let anyone realize that she can see. When the hospital’s micro-society — perhaps a Jack London-like metaphor for society’s underclass — erupts, and destroys the institution, its freed inmates discover that the outside world is devastated. The doctor’s wife and her group must now fend for themselves like castaways; their eyes are opened, if you will, to the perversities and injustice of life in a merciless capitalist social order. The book’s harrowing moral, if there is one, comes from our tough, compassionate, almost saintly heroine: “I don’t think we did go blind, I think we are blind, Blind but seeing, Blind people who can see, but do not see.” Fun facts: When Saramago was awarded the 1998 Nobel Prize for Literature, Blindness was one of his works praised by the committee. A 2004 sequel, which I haven’t read, is titled Ensaio sobre a lucidez. A 2007 adaptation by director Fernando Meirelles, starring Julianne Moore and Mark Ruffalo, isn’t great — but it has its moments.

- Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist adventure Clay’s Ark (1984). In the year 2021, a doctor named Blake and his teenage daughters are captured by Eli Doyle, the only survivor of Clay’s Ark, a spaceship that — upon its return from the first manned mission to Proxima Centauri — has crash-landed in southeastern California’s Mojave Desert. Infected with an alien microorganism that gives him heightened sensory and physical powers, but which compels him to transmit the infection to others via sexual contact, Eli has isolated himself on an isolated ranch… where he and others whom he’s captured (all of whom have been altered, by the microorganism, in ways that allow them to survive and thrive) are raising their sphinx-like offspring — intelligent quadruped mutants who perceive uninfected humans as food, and who can spread the microorganism through their bite. Society, meanwhile, has devolved into armed enclaves, marauding “car families,” and other post-apocalyptic phenomena. Blake and his daughters must decide whether to resign themselves to living within Eli’s enclave… or escape, and risk not only being captured by even worse predators, but aso creating an uncontrollable epidemic that could forever transform humankind. Though written last, Clay’s Ark is chronologically the third in the Patternist series. Fun facts: With the exception of Kindred in 1979, all of Butler’s earlier books are set in the Patternist universe. The first Patternist installment, Patternmaster, was published in 1976.

- Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials fantasy adventure Northern Lights (also published as The Golden Compass). In a universe parallel to our own, the world is dominated by the Magisterium, a Catholic Church-like global religious institution intolerant of heresy. Charmingly, in this world human souls exist outside of their bodies in the form of “dæmons,” protective spirits who take the form of animals. The dæmons may have something to do with mysterious elementary particles, or “Dust,” scientific investigations into the nature of which the Magisterium dissuades. When Lord Asriel, a swashbuckling scientist planning a journey to the Arctic in order to study the (possible extra-dimensional) origin of Dust, is nearly incapacitated or murdered by an agent of the Magisterium, his 12-year-old niece Lyra — a bright but semi-feral child raised by the scholars of Oxford — is determined to assist him in his quest. Child abductors known as the “Gobblers” abduct Lyra’s friend Roger, and Lyra is taken under the wing of a Mrs. Coulter — a Magisterium agent and, we learn, head of the Gobblers. Soon, a fugitive Lyra is headed north in the company of nomadic ’Gyptians; on her journey, she will encounter witches, a talking polar bear, and an aeronaut. It’s a fun thrill-ride, one guided by Lyra’s reading of an “alethiometer”…. Fun facts: The novel’s alternate title is not a reference to the alethiometer, but to the drafting compass that God used to establish the boundary of all creation in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Northern Lights, which was awarded a Carnegie Medal, was adapted as a 2007 movie featuring Nicole Kidman, Dakota Blue Richards, Daniel Craig, and Sam Elliott; the BBC’s 2019 TV adaptation looks superior. PS: I don’t love the other installments in the His Dark Materials series, I’m sorry to report.

- Ken MacLeod’s Fall Revolution sci-fi adventure The Star Fraction. In a balkanized Britain just a few hundred years from now, Moh Kohn, a smartgun-brandishing Trotskyist mercenary, finds himself embroiled in a revolution against the US/UN — a meta-dictatorship which made itself the neutral arbiter of international security in the wake of World War Three. The US/UN does not rule directly, but instead enforces a set of (sometimes secret) laws over a vast number of global microstates; for example, certain avenues of research, such as intelligence augmentation or artificial intelligence, are prohibited. The revolution, it seems, was set into motion by the Watchmaker, a financial software that may have evolved into an AI — thanks to the illicit work of Janis Taine, a scientist working on memory-enhancing drugs. Along with Janis and Jordan, a teenage atheist and hacker from a fundamentalist Christian microstate, Moh must evade the US/UN’s spy satellites — while navigating the violent squabbles of communists, socialists, libertarians, and anarchists. The book, which is replete with Marxist puns and in-jokes, is a throwback to cyberpunk: interfacing technology, biological enhancements, mind-altering drugs, a vibrant underworld. If the plot is too frenetic, and the characters underdeveloped, that’s OK — it’s the author’s first outing. I don’t understand it, but I enjoy it. Fun fact: MacLeod, a Scottish author, continued the Fall Revolution series with The Stone Canal (1996) and The Cassini Division (1998). The Sky Road (1999), meanwhile, represents an alternate sequel to The Stone Canal.

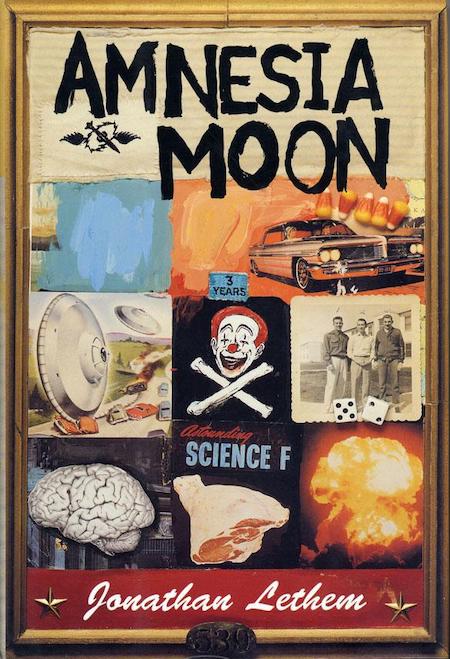

- Jonathan Lethem‘s sci-fi adventure Amnesia Moon. A post-apocalyptic picaresque, set in a fragmented future America in which the world as we know it has ended… subjectively speaking. Chaos, whose name may also be Everett Moon, or something else altogether, lives in an abandoned megaplex in Wyoming. Because his dreams are colonized by the more powerful dreams of Kellogg, an irreverent local guru and not-so-strong strongman, Chase hits the road — accompanied by Melinda, a fur-covered young girl. They visit an area covered in a thick green fog, save for an exclusive private school; and a Californian town that has converted to a luck-based social system. There are overt and covert meta-textual references to works by Philip K. Dick, Cornell Woolrich, Jack Kerouac, and Wim Wenders; at one point we hear of a West Marin inhabitant named “Hoppington,” a shout-out to the mutant telepath villain of Dick’s Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb. Televangelists in San Francisco have become robots, soap operas star government figures, Los Angeles is overrun by aliens! Along the way, Chaos learns more about his own past, and his own abilities. The narrative thread holding these excursions together is the notion that, in this post-whatever-happened world, reality is shaped — locally, even parochially — by those few individuals able to influence those around them to subscribe to their own subjective worldview. Fun fact: In interviews, Lethem later explained that Amnesia Moon is “a fix-up of unpublished short stories. I was trying to write out an obsession with dystopias, with collapsed or oppressed realities. At some point, I took a step back and said, ‘What am I trying to do here? Why are all the stories similar?’ The genesis of Amnesia Moon is my conclusion that what they had in common was this kind of need on the part of the characters, and apparently the author, to have the world destroyed.”

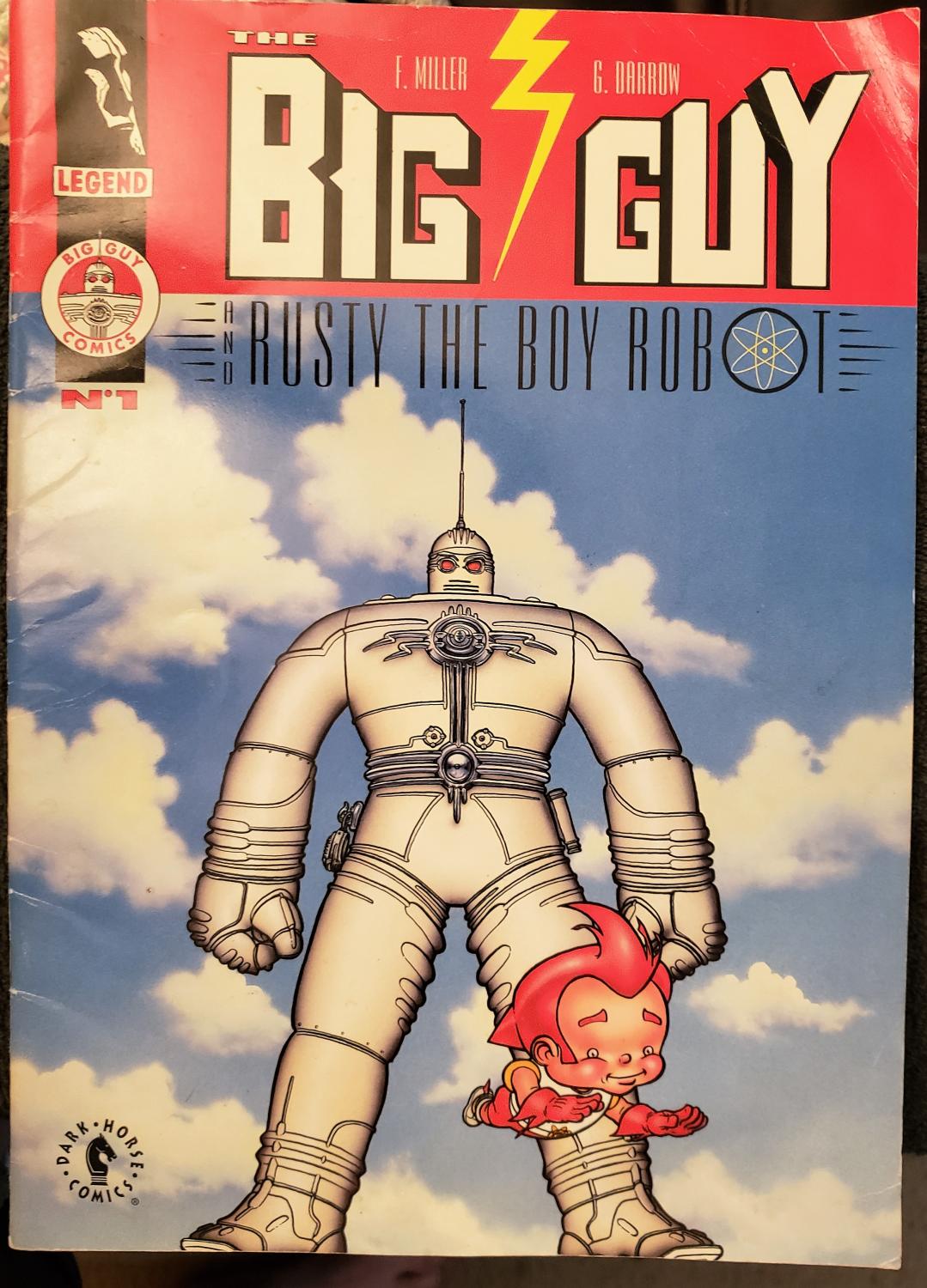

- Frank Miller and Geof Darrow’s comic The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot (serialized July-August 1995). Perhaps my favorite example of Geof Darrow’s work, The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot is a large-format pastiche of midcentury kaiju movies and Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy manga. As for Frank Miller’s story and script, it’s thrilling… but problematic, too, insofar as we can’t quite tell whether we’re supposed to laugh at the retro American triumphalism or applaud it. The Big Guy is an aircraft carrier-housed American WMD; Rusty the Boy Robot is his Japanese — more efficient, cuter — replacement. (Think WALL·E and EVE in WALL·E, or perhaps Burt Reynolds and Jan-Michael Vincent in Hooper.) When a Japanese experiment with primordial ooze goes wrong, and a giant reptilian creature begins to destroy Tokyo — and transform its citizens into monsters — Rusty springs into action, but fails to defeat the menace. Enter the Big Guy, who kicks ass while spouting American can-do homilies; squeamish readers might suspect that Miller is trolling us with this scenario, in which a Hiroshima-like event is Japan’s fault, and America plays the role of global peacekeeper. At the level of form, however, The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot is dazzling — epic in scale, yet incredibly detailed down to individual bullet shells and chunks of concrete. It’s a fucked-up masterpiece. Fun facts: The Big Guy first appeared in scattered pin-up and poster pages, before making a couple of appearances in Dark Horse’s Madman comics. The two-part comic reviewed here was adapted as a 1999–2001 animated series featuring Pamela Adlon as the voice of Rusty, and Jonathan David Cook as the voice of the Big Guy.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.