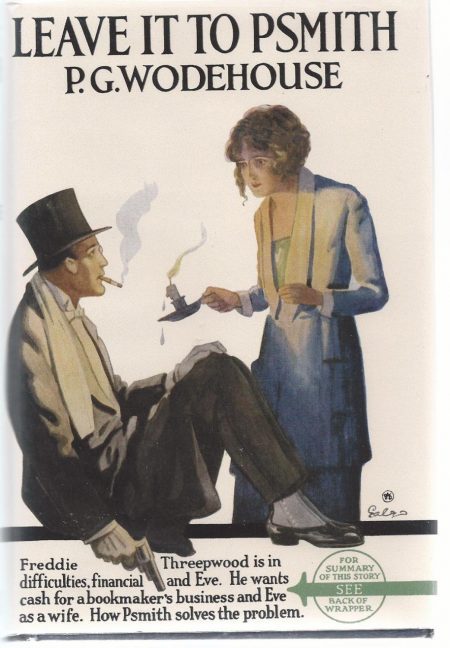

LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (20)

By:

May 27, 2019

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

‘I would prefer, if you do not mind,’ said Psmith, ‘to remain here for the moment and foster what I feel sure is about to develop into a great and lasting friendship. I feel that your son and I will have much to talk about together.’

‘Very well, my dear fellow. We will meet at dinner in the restaurant-car.’

Lord Emsworth pottered off, and Psmith rose and closed the door. He returned to his seat to find Freddie regarding him with a tortured expression in his rather prominent eyes. Freddie’s brain had had more exercise in the last few minutes than in years of his normal life, and he was feeling the strain.

‘I say, what?’ he observed, feebly.

‘If there is anything,’ said Psmith, kindly, ‘that I can do to clear up any little difficulty that is perplexing you, call on me. What is biting you?’

Freddie swallowed convulsively.

‘I say, he said your name was McTodd!’

‘Precisely.’

‘But you said we were at Eton together.’

‘Distinctly.’

‘I don’t remember you.’

‘And yet I gave you every cause to, Comrade Threepwood. I recollect administering six of the best and juiciest to you with the back of a hair-brush on one occasion when you and other bright spirits sneaked into my room and started to upset the furniture.’

Memory woke like a flash in the Hon. Freddie.

‘Great Scott! I remember!’

‘I thought you would. I took considerable pains to impress my personality on you.’

‘But — — Good Lord! Of course I remember you now — your name was Smith.’

‘It still is. Psmith. The p is silent.’

‘But father called you McTodd.’

‘He thinks I am. It is a harmless error, and I see no reason why it should be discouraged.’

‘But why does he think you’re McTodd?’

‘It is a long story, which you may find tedious. But, if you really wish to hear it…’

Nothing could have exceeded the raptness of Freddie’s attention as he listened to the tale of the encounter with Lord Emsworth at the Senior Conservative Club.

‘Do you mean to say,’ he demanded, at its conclusion, ‘that you’re coming to Blandings pretending to be this poet blighter?’

‘That is the scheme.’

‘But why?’

‘I have my reasons, Comrade Threepwood. You will pardon me if I do not go into them. And now,’ said Psmith, ‘to resume our very interesting chat which was unfortunately cut short this morning, why do you want me to steal your aunt’s necklace?’

Freddie jumped. For the moment, so tensely had the fact of his companion’s audacity chained his interest, he had actually forgotten about the necklace.

‘Great Scott!’ he exclaimed. ‘Why, of course!’

‘You still have not made it quite clear.’

‘It fits splendidly.’

‘The necklace?’

‘I mean to say, the great difficulty would have been to find a way of getting you into the house, and here you are, coming there as this poet bird. Topping!’

‘If,’ said Psmith, regarding him patiently through his eyeglass, ‘I do not seem to be immediately infected by your joyous enthusiasm, put it down to the fact that I haven’t the remotest idea what you’re talking about. Could you give me a pointer or two? What, for instance, assuming that I agreed to steal your aunt’s necklace, would you expect me to do with it, when and if stolen?’

‘Why, hand it over to me.’

‘I see. And what would you do with it?’

‘Hand it over to my uncle.’

‘And whom would he hand it over to?’

‘Look here,’ said Freddie, ‘I might as well start at the beginning.’

‘An excellent idea.’

The speed at which the train was now proceeding had begun to render conversation in anything but stentorian tones somewhat difficult. Freddie accordingly bent forward till his mouth almost touched Psmith’s ear.

‘You see, it’s like this. My uncle, old Joe Keeble …’

‘Keeble?’ said Psmith. ‘Why,’ he murmured, meditatively, ‘is that name familiar?’

‘Don’t interrupt, old lad,’ pleaded Freddie.

‘I stand corrected.’

‘Uncle Joe has a step-daughter — Phyllis her name is, and some time ago she popped off and married a cove called Jackson …’

Psmith did not interrupt the narrative again, but as it proceeded his look of interest deepened. And at the conclusion he patted his companion encouragingly on the shoulder.

‘The proceeds, then, of this jewel-robbery, if it comes off,’ he said, ‘will go to establish the Jackson home on a firm footing? Am I right in thinking that?’

‘Absolutely.’

‘There is no danger — you will pardon the suggestion — of you clinging like glue to the swag and using it to maintain yourself in the position to which you are accustomed?’

‘Absolutely not. Uncle Joe is giving me — er — giving me a bit for myself. Just a small bit, you understand. This is the scheme. You sneak the necklace and hand it over to me. I push the necklace over to Uncle Joe, who hides it somewhere for the moment. There is the dickens of a fuss, and Uncle Joe comes out strong by telling Aunt Constance that he’ll buy her another necklace, just as good. Then he takes the stones out of the necklace, has them reset, and gives them to Aunt Constance. Looks like a new necklace, if you see what I mean. Then he draws a cheque for twenty thousand quid, which Aunt Constance naturally thinks is for the new necklace, and he shoves the money somewhere as a little private account. He gives Phyllis her money, and everybody’s happy. Aunt Constance has got her necklace, Phyllis has got her money, and all that’s happened is that Aunt Constance’s and Uncle Joe’s combined bank-balance has had a bit of a hole knocked in it. See?’

‘I see. It is a little difficult to follow all the necklaces. I seemed to count about seventeen of them while you were talking, but I suppose I was wrong. Yes, I see, Comrade Threepwood, and I may say at once that you can rely on my co-operation.’

‘You’ll do it?’

‘I will.’

‘Of course,’ said Freddie, awkwardly, ‘I’ll see that you get a bit all right. I mean …’

Psmith waved his hand deprecatingly.

‘My dear Comrade Threepwood, let us not become sordid on this glad occasion. As far as I am concerned, there will be no charge.’

‘What! But look here …’

‘Any assistance I can give will be offered in a purely amateur spirit. I would have mentioned before, only I was reluctant to interrupt you, that Mike Jackson is my boyhood chum, and that Phyllis, his wife, injects into my life the few beams of sunshine that illumine its dreary round. I have long desired to do something to ameliorate their lot, and now that the chance has come I am delighted. It is true that I am not a man of affluence — my bank-manager, I am told, winces in a rather painful manner whenever my name is mentioned — but I am not so reduced that I must charge a fee for performing on behalf of a pal a simple act of courtesy like pinching a twenty-thousand-pound necklace.’

‘Good Lord! Fancy that!’

‘Fancy what, Comrade Threepwood?’

‘Fancy your knowing Phyllis and her husband.’

‘It is odd, no doubt. But true. Many a whack at the cold beef have I had on Sunday evenings under their roof, and I am much obliged to you for putting in my way this opportunity of repaying their hospitality. Thank you!’

‘Oh, that’s all right,’ said Freddie, somewhat bewildered by this eloquence.

‘Even if the little enterprise meets with disaster, the reflection that I did my best for the young couple will be a great consolation to me when I am serving my bit of time in Wormwood Scrubbs. It will cheer me up. The jailers will cluster outside the door to listen to me singing in my cell. My pet rat, as he creeps out to share the crumbs of my breakfast, will wonder why I whistle as I pick the morning’s oakum. I shall join in the hymns on Sundays in a way that will electrify the chaplain. That is to say, if anything goes wrong and I am what I believe is technically termed ‘copped.’

‘I say ‘If,’’ said Psmith, gazing solemnly at his companion. ‘But I do not intend to be copped. I have never gone in largely for crime hitherto, but something tells me I shall be rather good at it. I look forward confidently to making a nice, clean job of the thing. And now, Comrade Threepwood, I must ask you to excuse me while I get the half-Nelson on this rather poisonous poetry of good old McTodd’s. From the cursory glance I have taken at it, the stuff doesn’t seem to mean anything. I think the boy’s deranged. You don’t happen to understand the expression ‘Across the pale parabola of Joy,’ do you? … I feared as much. Well, pip-pip for the present, Comrade Threepwood. I shall now ask you to retire into your corner and amuse yourself for awhile as you best can. I must concentrate, concentrate.’

And Psmith, having put his feet up on the opposite seat and reopened the mauve volume, began to read. Freddie, his mind still in a whirl, looked out of the window at the passing scenery in a mood which was a nice blend of elation and apprehension.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.