LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (14)

By:

April 6, 2019

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

‘Thanks, Zadkiel,’ said the young man. ‘Deuced gratifying, I’m sure. I suppose you couldn’t predict the winner of the Goodwood Cup as well?’

He then withdrew rapidly to intercept a young woman in a large hat who had just come through the swing doors. Psmith was forced to the conclusion that this was not his man. He was sorry on the whole, for he had seemed a pleasant fellow.

As Psmith had taken up a stationary position and the population of the lobby was for the most part in a state of flux, he was finding himself next to someone new all the time; and now he decided to accost the individual whom the re-shuffle had just brought elbow to elbow with him. This was a jovial- looking soul with a flowered waistcoat, a white hat, and a mottled face. Just the man who might have written that letter.

The effect upon this person of Psmith’s meteorological remark was instantaneous. A light of the utmost friendliness shone in his beautifully shaven face as he turned. He seized Psmith’s hand and gripped it with a delightful heartiness. He had the air of a man who has found a friend, and what is more, an old friend. He had a sort of journeys-end-in-lovers’-meeting look.

‘My dear old chap!’ he cried. ‘I’ve been waiting for you to speak for the last five minutes. Knew we’d met before somewhere, but couldn’t place you. Face familiar as the dickens, of course. Well, well, well! And how are they all?’

‘Who?’ said Psmith courteously.

‘Why, the boys, my dear chap.’

‘Oh, the boys?’

‘The dear old boys,’ said the other, specitying more exactly. He slapped Psmith on the shoulder, ‘What times those were, eh?’

‘Which?’ said Psmith.

‘The times we all used to have together.’

‘Oh, those?’ said Psmith.

Something of discouragement seemed to creep over the other’s exuberance, as a cloud creeps over the summer sky. But he persevered.

‘Fancy meeting you again like this!’

‘It is a small world,’ agreed Psmith.

‘I’d ask you to come and have a drink,’ said the jovial one, with the slight increase of tensity which comes to a man who approaches the core of a business deal, ‘but the fact is my ass of a man sent me out this morning without a penny. Forgot to give me my note-case. Damn careless! I’ll have to sack the fellow.’

‘Annoying, certainly,’ said Psmith.

‘I wish I could have stood you a drink,’ said the other wistfully.

‘Of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these, “It might have been”,’ sighed Psmith.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ said the jovial one, inspired. ‘Lend me a fiver, my dear old boy. That’s the best way out of the difficulty. I can send it round to your hotel or wherever you are this evening when I get home.’

A sweet, sad smile played over Psmith’s face.

‘Leave me, comrade!’ he murmured.

‘Eh?’

‘Pass along, old friend, pass along.’

Resignation displaced joviality in the other’s countenance.

‘Nothing doing?’ he inquired.

‘Nothing.’

‘Well, there was no harm in trying,’ argued the other.

‘None whatever.’

‘You see,’ said the now far less jovial man confidentially, ‘you look such a perfect mug with that eyeglass that it tempts a chap.’

‘I can quite understand how it must!’

‘No offence.’

‘Assuredly not.’

The white hat disappeared through the swing doors, and Psmith returned to his quest. He engaged the attention of a middle-aged man in a snuff-coloured suit who had just come within hail.

‘There will be rain in Northumberland to-morrow,’ he said.

The man peered at him inquiringly.

‘Hey?’ he said.

Psmith repeated his observation,

‘Hey?’ said the man.

Psmith was beginning to lose the unruffled calm which made him such an impressive figure to the public eye. He had not taken into consideration the possibility that the object of his search might be deaf. It undoubtedly added to the embarrassment of the pursuit. He was moving away, when a hand fell on his sleeve.

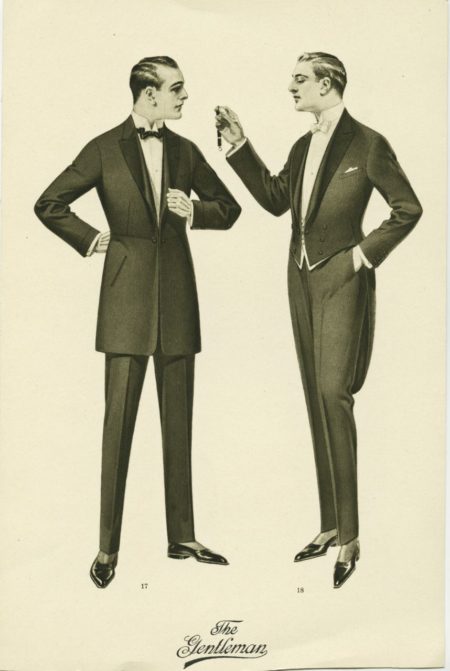

Psmith turned. The hand which still grasped his sleeve belonged to an elegantly dressed young man of a somewhat nervous and feverish appearance. During his recent vigil Psmith had noticed this young man standing not far away, and had had half a mind to include him in the platoon of new friends he was making that morning.

‘I say,’ said this young man in a tense whisper, ‘did I hear you say that there would be rain in Northumberland to-morrow?’

‘If,’ said Smith, ‘you were anywhere within the radius of a dozen yards while I was chatting with the recent deaf adder, I think it is possible that you did.’

‘Good for the crops,’ said the young man. ‘Come over here where we can talk quietly.’

‘So you’re R. Psmith?’ said the young man, when they had made their way to a remote corner of the lobby, apart from the throng.

‘The same.’

‘I say, dash it, you’re frightfully late, you knew. I told you to be here at twelve sharp. It’s nearly twelve past.’

‘You wrong me,’ said Psmith. ‘I arrived here precisely at twelve. Since when, I have been standing like Patience on a monument…’

‘Like what?’

‘Let it go,’ said Psmith. ‘It is not important.’

‘I asked you to wear a pink chrysanthemum. So I could recognize you, you know.’

‘I am wearing a pink chrysanthemum. I should have imagined that that was a fact that the most casual could hardly have overlooked.’

‘That thing?’ The other gazed disparagingly at the floral decoration. ‘I thought it was some kind of cabbage. I meant one of those little what-d’you-may-call-its that people wear in their button-holes.’

‘Carnation, possibly.’

‘Carnation! That’s right.’

Psmith removed the chrysanthemum and dropped it behind his chair. He looked at his companion reproachfully.

‘If you had studied botany at school, comrade,’ he said, ‘much misery might have been averted. I cannot begin to tell you the spiritual agony I suffered, trailing through the metropolis behind that shrub.’

Whatever decent sympathy and remorse the other might have shown at these words was swept away in the shock resultant on a glance at his watch. Not for an instant during this brief return of his to London had Freddie Threepwood been unmindful of his father’s stern injunction to him to catch the twelve-fifty train back to Market Blandings. If he missed it, there would be the deuce of a lot of unpleasantness, and unpleasantness in the home was the one thing Freddie wanted to avoid nowadays, for, like a prudent convict in a prison, he hoped by exemplary behavior to get his sentence of imprisonment at Blandings Castle reduced for good conduct.

‘Good Lord! I’ve only got about five minutes. Got to talk quick. … About this thing. This business. That advertisement of yours.’

‘Ah, yes. My advertisement. It interested you?’

‘Was it on the level?’

‘Assuredly. We Psmiths do not deceive.’

Freddie looked at him doubtfully.

‘You know, you aren’t a bit like I expected you’d be.’

‘In what respect.’ inquired Psmith, ‘do I fall short of the ideal?’

‘It isn’t so much falling short. It’s — oh, I don’t know… Well, yes, if you want to know, I thought you’d be a tougher specimen altogether. I got the impression from your advertisement that you were down and out and ready for anything, and you look as if you were on your way to a garden-party at Buckingham Palace.’

‘Ah!’ said Psmith, enlightened. ‘It is my costume that is causing these doubts in your mind. This is the second time this morning that such a misunderstanding has occurred. Have no misgivings. These trousers may sit well, but, if they do, it is because the pockets are empty.’

‘Are you really broke!’

‘As broke as the Ten Commandments.’

‘I’m hanged if I can believe it.’

‘Suppose I brush my hat the wrong way for a moment?’ said Psmith obligingly. ‘Would that help?’

His companion remained silent for a few moments. In spite of the fact that he was in so great a hurry and that every minute that passed brought nearer the moment when he would be compelled to tear himself away and make a dash for Paddington Station, Freddie was finding it difficult to open the subject he had come there to discuss.

‘Look here,’ he said at length, ‘I shall have to trust you, dash it.’

‘You could pursue no better course.’

‘It’s like this. I’m trying to raise a thousand quid…’

‘I regret that I cannot offer to advance it to you myself. I have, indeed, already been compelled to decline to lend a gentleman who claimed to be an old friend of mine so small a sum as a fiver. But there is a dear obliging soul of the name of Alistair MacDougall who…’

‘Good Lord! You don’t think I’m trying to touch you?’

‘That impression did flit through my mind.’

‘Oh, dash it, no. No, but — well, as I was saying, I’m frightfully keen to get hold of a thousand quid.’

‘So am I,’ said Psmith. ‘Two minds with but a single thought. How do you propose to start about it? For my part, I must freely confess that I haven’t a notion, I am stumped. The cry goes round the chancelleries, “Psmith is baffled!”’

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.