LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (2)

By:

January 8, 2019

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

‘Lady Constance has long been a great admirer of his work. She wrote inviting him, should he ever come to England, to pay a visit to Blandings. He is now in London and is to come down to-morrow for two weeks. Lady Constance’s suggestion was that, as a compliment to Mr McTodd’s eminence in the world of literature, you should meet him in London and bring him back here yourself.’

Lord Emsworth remembered now. He also remembered that this positively infernal scheme had not been his sister Constance’s in the first place. It was Baxter who had made the suggestion, and Constance had approved. He made use of the recovered pince-nez to glower through them at his secretary; and not for the first time in recent months was aware of a feeling that this fellow Baxter was becoming a dashed infliction. Baxter was getting above himself, throwing his weight about, making himself a confounded nuisance. He wished he could get rid of the man. But where could he find an adequate successor? That was the trouble. With all his drawbacks, Baxter was efficient. Nevertheless, for a moment Lord Emsworth toyed with the pleasant dream of dismissing him. And it is possible, such was his exasperation, that he might on this occasion have done something practical in that direction, had not the library door at this moment opened for the third time, to admit yet another intruder — at the sight of whom his lordship’s militant mood faded weakly.

‘Oh — hallo, Connie!’ he said, guiltily, like a small boy caught in the jam cupboard. Somehow his sister always had this effect upon him.

Of all those who had entered the library that morning the new arrival was the best worth looking at. Lord Emsworth was tall and lean and scraggy; Rupert Baxter thick-set and handicapped by that vaguely grubby appearance which is presented by swarthy young men of bad complexion; and even Beach, though dignified, and Freddie, though slim, would never have got far in a beauty competition. But Lady Constance Keeble really took the eye. She was a strikingly handsome woman in the middle forties. She had a fair, broad brow, teeth of a perfect even whiteness, and the carriage of an empress. Her eyes were large and grey, and gentle — and incidentally misleading, for gentle was hardly the adjective which anybody who knew her would have applied to Lady Constance. Though genial enough when she got her way, on the rare occasions when people attempted to thwart her she was apt to comport herself in a manner reminiscent of Cleopatra on one of the latter’s bad mornings.

‘I hope I am not disturbing you,’ said Lady Constance with a bright smile, ‘I just came in to tell you to be sure not to forget, Clarence, that you are going to London this afternoon to meet Mr McTodd.’

‘I was just telling Lord Emsworth,’ said Baxter, ‘that the car would be at the door at two.’

‘Thank you, Mr Baxter. Of course I might have known that you would not forget. You are so wonderfully capable. I don’t know what in the world we would do without you.’

The Efficient Baxter bowed. But, though gratified, he was not overwhelmed by the tribute. The same thought had often occurred to him independently.

‘If you will excuse me,’ he said, ‘I have one or two things to attend to.’

‘Certainly, Mr Baxter.’

The Efficient One withdrew through the door in the bookshelf. He realized that his employer was in fractious mood, but knew that he was leaving him in capable hands.

Lord Emsworth turned from the window, out of which he had been gazing with a plaintive detachment.

‘Look here, Connie,’ he grumbled feebly. ‘You know I hate literary fellows. It’s bad enough having them in the house, but when it comes to going to London to fetch ’em….’

He shuffled morosely. It was a perpetual grievance of his, this practice of his sister’s of collecting literary celebrities and dumping them down in the home for indeterminate visits. You never knew when she was going to spring another on you. Already since the beginning of the year he had suffered from a round dozen of the species at brief intervals; and at this very moment his life was being poisoned by the fact that Blandings was sheltering a certain Miss Aileen Peavey, the mere thought of whom was enough to turn the sunshine off as with a tap.

‘Can’t stand literary fellows,’ proceeded his lordship. ‘Never could. And, by Jove, literary females are worse. Miss Peavey…’ Here words temporarily failed the owner of Blandings. ‘Miss Peavey,’ he resumed after an eloquent pause, ‘Who is Miss Peavey?’

‘My dear Clarence,’ replied Lady Constance tolerantly, for the fine morning had made her mild and amiable, ‘if you do not know that Aileen is one of the leading poetesses of the younger school, you must be very ignorant.’

‘I don’t mean that. I know she writes poetry, I mean who is she? You suddenly produced her here like a rabbit out of a hat,’ said his lordship, in a tone of strong resentment. ‘Where did you find her?’

‘I first made Aileen’s acquaintance on an Atlantic liner when Joe and I were coming back from our trip round the world. She was very kind to me when I was feeling the motion of the vessel. If you mean what is her family, I think Aileen told me once that she was connected with the Rutlandshire Peaveys.’

‘Never heard of them!’ snapped Lord Emsworth. ‘And if they’re anything like Miss Peavey, God help Rutlandshire!’

Tranquil as Lady Constance’s mood was this morning, an ominous stoniness came into her gray eyes at these words, and there is little doubt that in another instant she would have discharged at her mutinous brother one of those shattering comebacks for which she had been celebrated in the family from nursery days onward; but at this juncture the Efficient Baxter appeared again through the bookshelf.

‘Excuse me,’ said Baxter, securing attention with a flash of his spectacles. ‘I forgot to mention, Lord Emsworth, that, to suit everybody’s convenience, I have arranged that Miss Halliday shall call to see you at your club to-morrow after lunch.’

‘Good Lord, Baxter!’ The harassed peer started as if he had been bitten in the leg. ‘Who’s Miss Halliday? Not another literary female?’

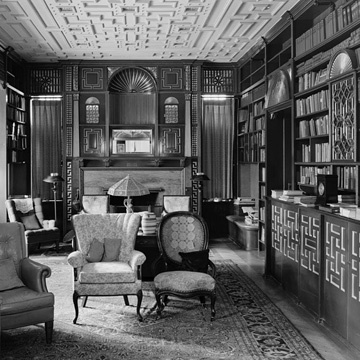

‘Miss Halliday is the young lady who is coming to Blandings to catalogue the library.’

‘Catalogue the library? What does it want cataloguing for?’

‘It has not been done since the year 1885.’

‘Well, and look how splendidly we’ve got along without it,’ said Lord Emsworth acutely.

‘Don’t be so ridiculous, Clarence,’ said Lady Constance, annoyed. ‘The catalogue of a great library like this must be brought up to date.’ She moved to the door. ‘I do wish you would try to wake up and take an interest in things. If it wasn’t for Mr Baxter, I don’t know what would happen.’

And with a beaming glance of approval at her ally she left the room. Baxter, coldly austere, returned to the subject under discussion.

‘I have written to Miss Halliday suggesting two-thirty as a suitable hour for the interview.’

‘But look here…’

‘You will wish to see her before definitely confirming the engagement.’

‘Yes, but look here, I wish you wouldn’t go tying me up with all these appointments.’

‘I thought that as you were going to London to meet Mr McTodd…’

‘But I’m not going to London to meet Mr McTodd,’ cried Lord Emsworth with weak fury. ‘It’s out of the question. I can’t possibly leave Blandings, the weather may break at any moment. I don’t want to miss a day of it.’

‘The arrangements are all made.’

‘Send the fellow a wire… ‘unavoidably detained’.’

‘I could not take the responsibility for such a course myself,’ said Baxter coldly. ‘But possibly if you were to make the suggestion to Lady Constance…’

‘Oh, dash it!’ said Lord Emsworth unhappily, at once realizing the impossibility of the scheme. ‘Oh, well, if I’ve got to go, I’ve got to go,’ he said after a gloomy pause. ‘But to leave my garden and stew in London at this time of the year…’

There seemed nothing further to say on the subject. He took off his glasses, polished them, put them on again, and shuffled to the door. After all, he reflected, even though the car was coming for him at two, at least he had the morning, and he proposed to make the most of it. But his first careless rapture at the prospect of pottering among his flowers was dimmed, and would not be recaptured. He did not entertain any project so mad as the idea of defying his sister Constance, but he felt extremely bitter about the whole affair. Confound Constance! … Dash Baxter! … Miss Peavey …

The door closed behind Lord Emsworth.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.