BESTIARY (1)

By:

January 19, 2021

One in a series of posts — curated by Matthew Battles — the ultimate goal of which is a high-lowbrow bestiary.

One day Yanguan called to his attendant, “Bring me my rhinoceros horn fan.”

The attendant said, “The fan is broken.”

Yanguan said, “If the fan is broken, bring me the rhinoceros.”

The attendant made no reply.

— 91st discourse of The Blue Cliff Record

For the Ch’an Buddhist masters of the Song Dynasty, the rhinoceros was likely as legendary as it would be for Dürer in Germany four centuries later. Although they had roamed China formely, by the tenth century, rhinoceros would have been scattered across South Asia; trade in their horns would have passed through jungles and over mountains.

Then as now, the horn of the rhinoceros was prized for its curative and fortifying properties. In 1993, the People’s Republic of China joined the CITES treaty governing global trade in endangered plants and animals, and removed the rhinoceros from the Pharmacopoeia of Traditional Chinese Medicine. And yet it remains in high demand.

Why Master Yanguan would have a fan made of rhinoceros horn is a mystery; such a fan would have been the plaything of magistrates, not mendicants.

Touzi said, “I wouldn’t mind bringing out the rhinoceros, though I’m afraid the horn on its head will be imperfect.” Xuedou commented, “I want to see that broken horn.”

— 91st discourse of The Blue Cliff Record

In 1740, ship captain Douwemoot van der Meer obtained a young Indian rhinoceros named Clara from the director of the Dutch East India Company and brought her back to Europe. Following acclaimed exhibitions in Antwerp, Brussels, and Hamburg, Clara and van der Meer went on tour, appearing at various European venues over the next two decades.

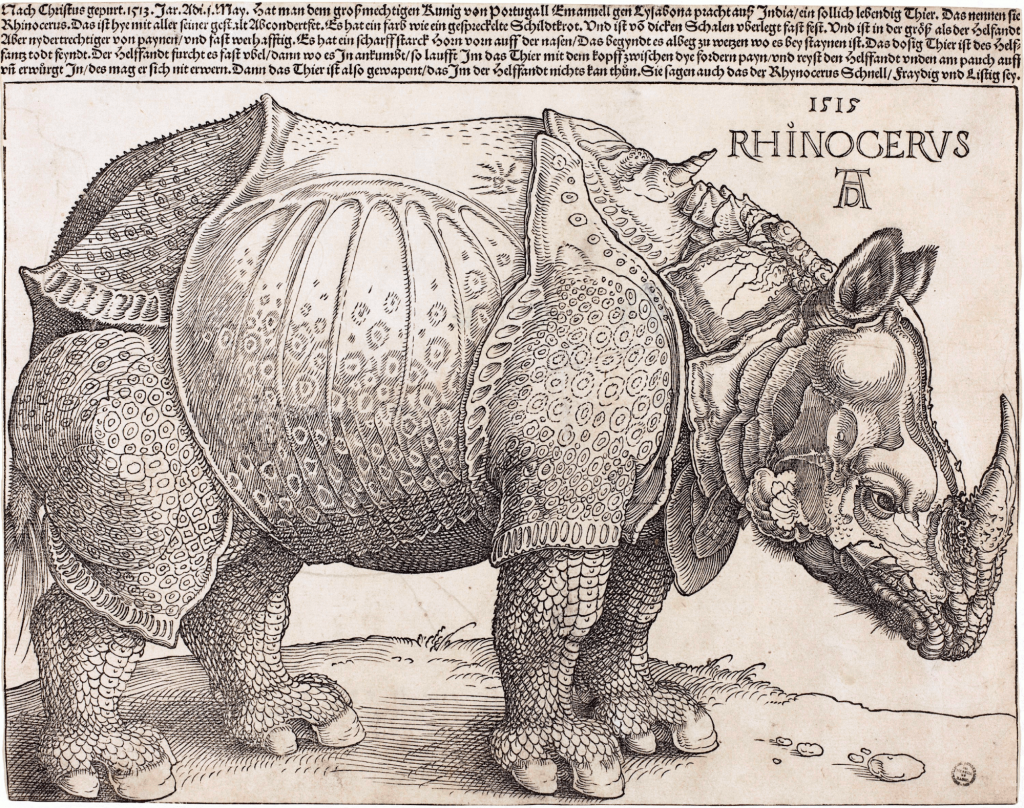

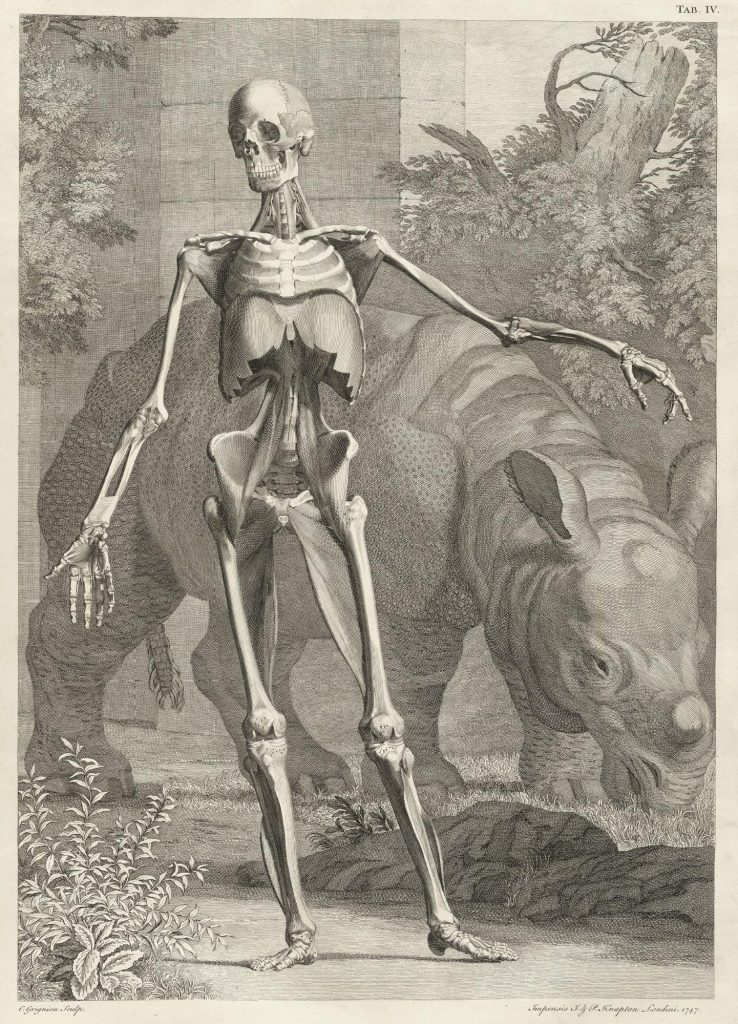

Clara was not the first rhinoceros to visit Europe since Albrecht Dürer produced his drawing (in 1515, after a rhinoceros exhibited in Lisbon; it remains perhaps the best-known Western image of a rhinoceros, though Dürer never saw the creature firsthand, but drew entirely on rumor and surmise). It was Clara’s long life in captivity and great fame, however, which transformed the rhinoceros from fable to familiarity in the West. She became the subject of a Meissen porcelain figurine, and appeared as a supporting player in Jan Wandelaar’s engravings for the Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani, a landmark 18th-century anatomical atlas by Bernhard Albinus, and in a score or more of paintings and drawings reproduced for the popular press.

Shishuang said, “If I bring it to the Master, then I won’t have it.” Xuedou commented, “The rhino is still there!”

— 91st discourse of The Blue Cliff Record

Clara’s story inspired South African artist William Kentridge, whose 2005 production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute features a video projection of a rhinoceros puppet in the artist’s signature stop-motion style. In the opera, Tamino receives a flute that gives him power over the animals; Kentridge’s Tamino masters no menagerie, however, but a single rhinoceros.

Kentridge’s rhino, unlike Clara, is a white rhinoceros, an endangered species in South Africa. In choosing Clara as a kind of muse, however, the artist connects with distinctly eighteenth-century urges and experiences. Over the long eighteenth century, as whole societies died of epidemic disease or were sold into slavery, the rhinoceros was transformed from a legendary being to a beast in a barn, from unicorn to hay-munching hulk. O, these menageries — all these sad parades by which the moderns came to manage their encounter with wild natures. In tricorn hats and liberty caps, bewigged and bedraggled, they discovered themselves in discovering others, denied their own variety and bewilderment in gazing on the spoiled plumage of their numberless captives.

Zifu drew a circle and wrote the word “rhino” inside it. Xuedou commented, “Why didn’t you bring it out before?”

— 91st discourse of The Blue Cliff Record

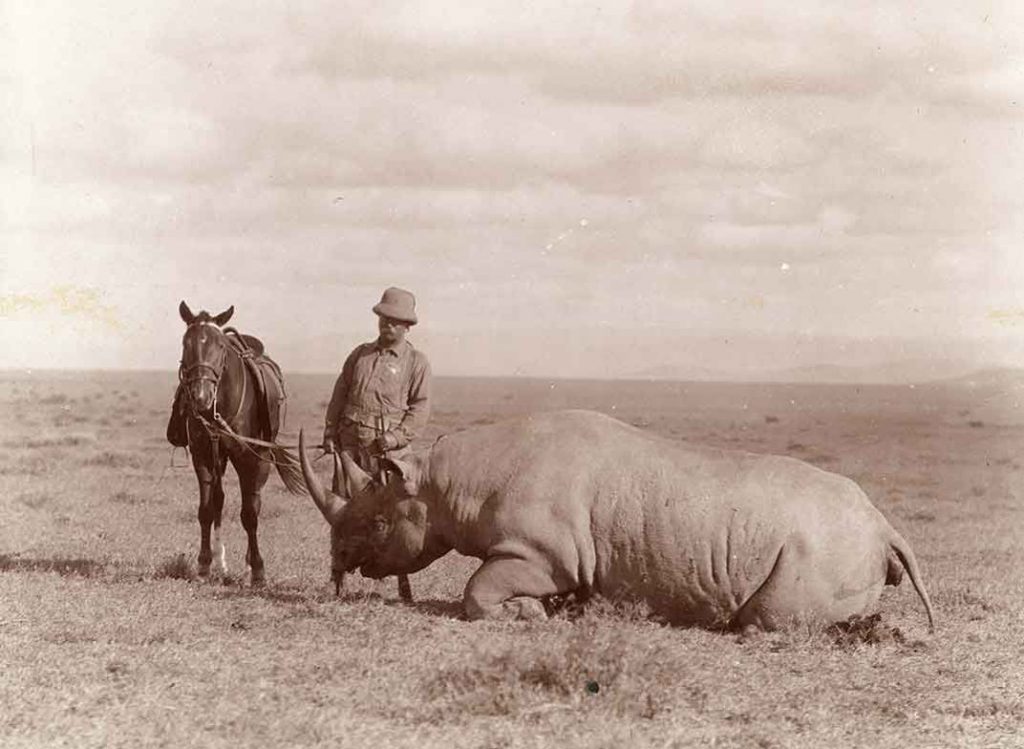

Shortly after leaving the presidency in March 1909, Teddy Roosevelt embarked on an expedition to eastern and central Africa on behalf of the Smithsonian Museum. The trip took Roosevelt and his entourage to Kenya and the Belgian Congo before following the Nile to its headwaters in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

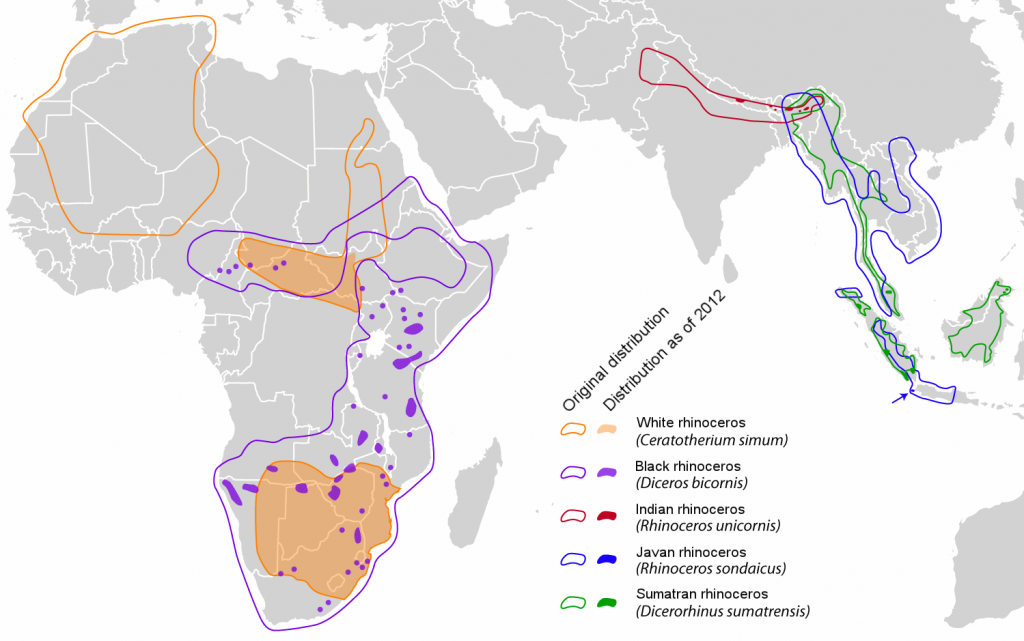

The expedition would ultimately collect more than 20,000 specimens; Roosevelt and his son alone shot more than 500 big-game animals — all slaughter done at the demand of science. And Roosevelt’s scientific cause célèbre on this journey was the white rhinoceros, which already was known to be on the brink of extinction across Africa. The remaining populations were scattered widely, mostly across the southern part of the continent, suggesting that the species had once been widespread across the continent and now was in inexorable decline. But in 1900, a group was found living in the Lado Enclave, a swampy territory on the edges of the Congo and Sudan, which the monstrous King Leopold claimed for his private shooting ground. To Roosevelt’s mind, this would be the museums’ last chance to collect specimens.

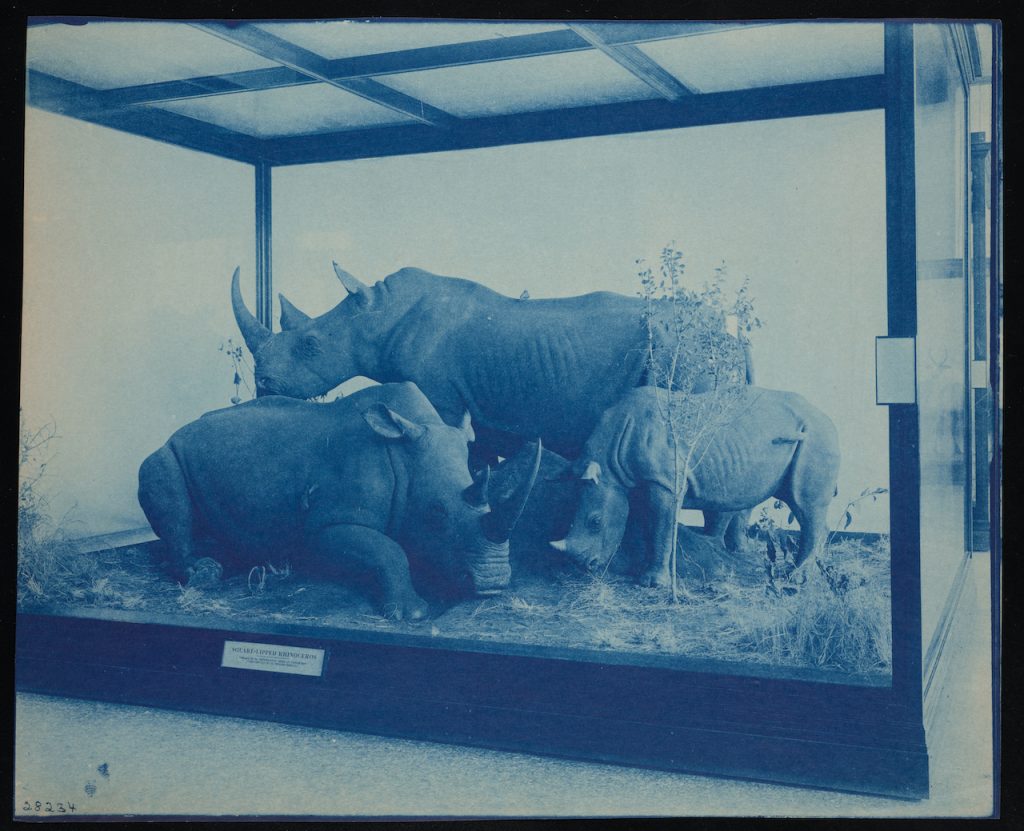

Venturing into the Lado, Roosevelt eventually shot six white rhinoceros. Smithsonian curators would take eight years cataloging Roosevelt’s quarry, turning tens of thousands of once-living things into data. The taxidermy grouping featuring his best specimens in the Smithsonian numbers three animals — more than the entire population of northern white rhinoceros in the world today. Of course, they were collected by a president. Like Yanguan’s fan, they make for a kingly prize, however broken.

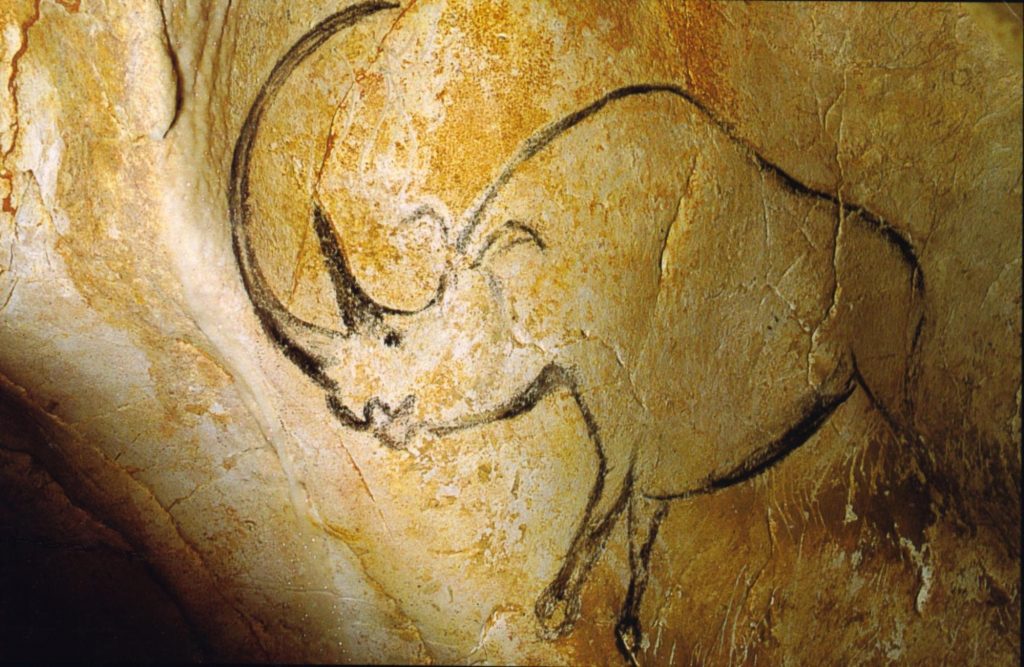

Thirty thousand years ago, people living in the Ardèche Valley of southern France painted the creatures with whom they shared the landscape of the mammoth steppe — once the earth’s largest biome, covering all the landmasses of the northern hemisphere, encompassing Europe and Asia. Some artist filled the grottos of Chauvet Cave with images of animals rendered in charcoal and ochre, paintings that teem with wooly rhinoceros — a creature that would have been common on the mammoth steppe, from Chauvet to China.

As with the territories of the white rhinoceros in the time of King Leopold and Teddy Roosevelt, today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken, like a Meissen figure dropped and then swept up, leaving only a few crumbs of porcelain scattered across the ground. Alongside the portraits by Dürer, Longhi, and Wandelaar, alongside the profiles left in Pleistocene caves and the traces of lost and broken horns in the koans, this broken map, too, is an image of the rhinoceros we have made.

Baofu said, “Master, you are so old; you should ask someone else.” Xuedou commented, “What a pity to have worked hard without accomplishing anything.”

— 91st discourse of The Blue Cliff Record

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.