The Scarlet Plague (Intro)

By:

January 6, 2018

In 2012, HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Jack London’s Radium Age sci-fi novel The Scarlet Plague (1912) in paperback form. Matthew Battles — author of Library: An Unquiet History, Letter by Letter, and the science fiction story collection The Sovereignties of Invention — provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

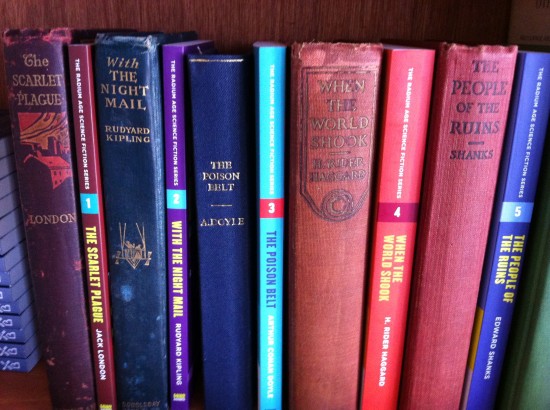

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

Dressed in furs, an old man and a gaggle of boys emerge from the undergrowth to survey crashing surf and an expanse of sea. One of the boys, armed with a bow, takes a rabbit with a skillful shot. It’s a scene from the verdant dawn of humankind. But there is a discordant note: water tumbles down the beach from an ancient culvert; in the undergrowth, the spotted steel of a forgotten railway gleams. The old man, whom the boys call Granser, begins impulsively to spin tales of the old times — an age of airships and wireless communication, of teeming cities and bustling commerce. He tells the incredulous boys about a terrible disease that killed swiftly and spread invisibly, turning faces scarlet — a word they do not know — and stopping hearts. The dead lay stacked in vast numbers — a scale of human life and death that the boys, children of a ragged tribe struggling in a vast unpeopled wilderness, can hardly conceive.

To imagine one’s own time as the pause before the fall; to be at the brink — is this a distinctively contemporary reflex? Is it an unavoidable outcome of the whole modern project of risk and progress? In The Scarlet Plague, even language has turned topsy-turvy in its progress, with feral babble normative, and sophisticated rhetoric a glimmer of the distant past:

The old man babbled on, unheeded by the boys, who were long accustomed to his garrulousness, and whose vocabularies, besides, lacked the greater portion of the words he used. It was noticeable that in these rambling soliloquies his English seemed to recrudesce into better construction and phraseology. But when he talked directly with the boys it lapsed, largely, into their own uncouth and simpler forms.

How vividly familiar we are with London’s post-apocalyptic world: a landscape emptied of people, where farm animals run feral and canned food lies in abandoned pantries. Airships fall from the sky; the cities burn; the countryside goes silent — the whole panoply of the post-Hiroshima eschaton, from Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to the proliferating zombie remixes of the late twenty-aughts, is already present in London’s Progressive-era imagination.

As familiar as their feral condition seems to us, to the children of London’s post-plague world, the teeming splendor of old — of our time — is inconceivable. Granser invites the boys to imagine crowds of “people, thicker than the salmon-run you have seen on the Sacramento river.” At the start of the novel, Granser and the boys face down a bear who now rules the former roadways of the coast, and the story closes as sea lions roll in the surf on an unpeopled beach. Throughout The Scarlet Plague, such images of a rejuvenated natural world index the fall of civilization. For London, nature is not mere counterpoint to society, but its source and foundation, a feral foreword we forget at our peril. “Though you stand on the top of the ladder of life, you must not kick out that ladder from under your feet” he had written in 1909, in an essay entitled “The Other Animals” —

You must not deny your relatives, the other animals. Their history is your history, and if you kick them to the bottom of the abyss, to the bottom of the abyss you go yourself. By them you stand or fall. What you repudiate in them you repudiate in yourself — a pretty spectacle, truly, of an exalted animal striving to disown the stuff of life out of which it is made, striving by use of the very reason that was developed by evolution to deny the processes of evolution that developed it. This may be good egotism, but it is not good science.

London’s is a literary imagination striving to make place for natural history not as the figured source book of myth, but as a force knit into every human act.

The Scarlet Plague’s bacteriological pessimism is striking, written as it was in a time when science was beginning to unsettle the microbe’s long and brutal reign over human health. In 1898, H.G. Wells felt sufficiently sanguine about the evolutionary agency of bacteria to make them the true heroes of War of the Worlds (1898), where it is germs who in the end become the saviors of humankind, a kind of sub-rosa Nietzschean immune system for the planet, a force that kills to make us stronger. “By the toll of a billion deaths,” Wells wrote in the end of his novel, with the Martians dying of infections trivial to Earthlings, “man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers; it would still be his were the Martians ten times as mighty as they are. For neither do men live nor die in vain.” The bacteriological fatalism of The Scarlet Plague troubles the triumphal vision of the progress of microbiology in the early twentieth century, which had seen the antiseptic method well established in surgery, the medical understanding of microbial disease making slow but steady progress, and the discovery of new species of bacteria that did not threaten but support human life. But in the new, post-pandemic Eden of The Scarlet Plague, such knowledge itself in the end is subject to the microbe’s unstoppable erasure —

You do not know what soap is, and I shall not tell you, for I am telling the story of the Scarlet Death…. Very many of the diseases came from what we called germs. Remember that word — germs. A germ is a very small thing. It is like a wood-tick, such as you find on the dogs in the spring of the year when they run in the forest. Only the germ is very small. It is so small that you cannot see it —

Here, the microbes are the invisible agents of death; at the same time, they’re tokens of knowledge — a lost world of knowledge, the age of science and discovery drowned in a global flood of social breakdown and global pandemic. From the start, Granser talks of the germs in the past tense, as if the fall of the Plague’s apocalypse had scoured even these from the world — as if they were somehow the fatal fruit of all that past knowledge, the wages of hubris, the secret engines of a cyclical history. The function of the apocalyptic tale, after all — arguably since the time of St. John the Divine — is not so much about preparing for the future as it is to draw attention to the present’s mundane iniquities.

For many readers, The Scarlet Plague will evoke “The Masque of the Red Death” by Edgar Allan Poe, that science-fictional precursor and pioneering dystopian, for whom virulent disease also figures as an angel of death come to punish decadence and political corruption. Only with London we’ve entered the realm of true science fiction in its so-called “hard” variety: London deploys the theoretical underpinnings of science in a speculative mode; it’s not some spiritual afflication but a scientifically-defensible epidemiology that underpins the fable. Indeed London’s aged narrator, Granser, remembers for his grandsons that the seeds of disaster were sown through the very success of humankind, as high populations sustained by technology gave the chance for new germs to arise and spread. Reviewing the scourges of late civilization, Granser’s memory is a empirically un-flinching as a report from the World Health Organization:

But in 1947 there arose a new disease that had never been seen before. It got into the bodies of babies of only ten months old or less, and it made them unable to move their hands and feet, or to eat, or anything; and the bacteriologists were eleven years in discovering how to kill that particular germ and save the babies.

The passage is a haunting premonition of polio, for which vaccine trials began in 1957. By 2010 in London’s imagined future, global population stands at eight billion — a worthy calculation on London’s part; in 2011 the global population hovers close to 7 billion, and the UN estimates global population should reach 8 billion some time in the 2020s. The pandemic in Scarlet Plague arrives in the summer of 2013; London is writing of our own time, and the world is in the midst of sorting out whether his work figures as alternative history or prophecy.

Today, we’re transfixed with images of rapidly-advancing global disease. Popular science books limn the perils of emergent disease in a world flattened by air travel and global commerce, and movies picture the zombie ravages of epidemic and social breakdown. While it’s easy to account for these notions by cataloging signal symptoms of late modernity — the ease of airline travel, the globalization of culture in the media, the rapid urbanization of formerly rural populations, the widening disparity between rich and poor — it’s striking to note that already in 1912, London had envisaged a global pandemic sweeping away nearly 9 billion people.

The advent of steam turbines in marine propulsion at the end of the nineteenth century meant that bigger, faster ships could ply the oceans, transporting unsettled human populations from continent to continent in numbers never before seen. Tesla’s dynamos, meanwhile, delivered the perilous miracle of electricity; in the midst of the great spinning turbines, the image of history as an implacable cycle had special resonance. When the Titanic went down in April 1912, it gave the world a lurid glimpse in miniature of social apocalypse: a glittering ship sliding into a frozen sea, the rich fighting for space on lifeboats while the poor drown in the tumult. But turbines are not the only harbingers of change; already in 1911, London is imagining air travel as a vector of disease. “Even the airships of the rich,” London writes, “fleeing for mountain and desert fastnesses, carried the germs —

Hundreds of these airships escaped to Hawaii, and not only did they bring the plague with them, but they found the plague already there before them. This we learned, by the despatches, until all order in San Francisco vanished, and there were no operators left at their posts to receive or send. It was amazing, astounding, this loss of communication with the world.

In the midst of a networked age, the stilling of a worldwide wireless communication is perhaps harder to conceive than it was in London’s era of transoceanic cables and flickering telegraphy. But it is no less resonant. It’s striking the extent to which London understands that communications networks — in his day so insistently clattering and mechanical, so unstable and prone to breakdown — become integral to the functioning of mass society.

In his reverie of cyclical history, Granser imagines future generations discovering not only the books of history and literature he has secreted away, but reinventing gunpowder as well:

The gunpowder will come. Nothing can stop it — the same old story over and over. Man will increase, and men will fight. The gunpowder will enable men to kill millions of men, and in this way only, by fire and blood, will a new civilization, in some remote day, be evolved. And of what profit will it be? Just as the old civilization passed, so will the new. It may take fifty thousand years to build, but it will pass. All things pass. Only remain cosmic force and matter, ever in flux, ever acting and reacting and realizing the eternal types — the priest, the soldier, and the king.

London’s vision of these cycles evokes the philosophy of history of eighteenth-century thinker Giambattista Vico, whose time saw the ascendancy of science, the beginnings of ostensibly benevolent, bureaucratic monarchies, and the end of religious warfare in Europe. But to Vico, these hallmarks of progress were already harbingers of a fall; the glories of civilization were also the seeds of an overweening pride that would bring us to the brink of tragic choices. Vico saw history as a system powered by our paradoxical drives: to poetry and reflection on the one hand, and “ferocity, avarice, and ambition” on the other. These opposed regimes act through society to produce history that cycles from primitive savagery to barbarian society to the majesty of civilization — and back, again and again.

JANUARY — APRIL 2012

Jack London, world-famous adventurer and author of The Call of the Wild, wrote several key works of Radium Age science fiction, including The Iron Heel (1908) and The Star Rover (1914). The Scarlet Plague (1912) is set in London’s hometown of San Francisco, California.

“London’s style is typically lush but his viewpoint is skeptical and dystopian … [the] story reminds us of the dangers we still court with our careless ways.” — The Times (1912)

“I knew Jack London was all about romanticizing nature and the frontier and primitive peoples and, you know, the wild. But this showed me a whole new realm of London’s ambivalence about civilization: The Scarlet Plague is not just among the first modern post-apocalyptic fictions — starting right about now, a global contagion wipes out nearly all 8 billion earthlings — but maybe the most Edenic and winsome one ever.” — Kurt Andersen (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.