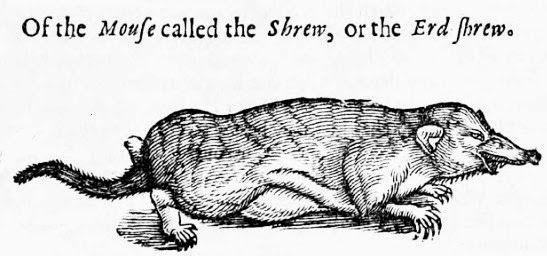

BESTIARY (14)

By:

October 3, 2021

One in a series of posts — curated by Matthew Battles — the ultimate goal of which is a high-lowbrow bestiary.

My first consciousness of the existence of the shrew was when I was assigned Konrad Lorenz’ 1952 book King Solomon’s Ring in high school. Lorenz, a Nobel prize-winning Austrian zoologist, is thought of as the founder of the field of ethology (the study of animal behavior), and served as a medic in the Nazi military (though he later regretted it).

Lorenz is the first person known to have successfully kept shrews—specifically, water shrews. His drawings of them are adorable. There is one image, of a fish tank with a tiny, flat-black blob with a tail and legs lying splayed out on its stomach at the bottom, which has always given me glee.

“All shrews,” explains Lorenz, “are particularly difficult to keep; this is not because, as we are led proverbially to believe, they are hard to tame, but because the metabolism of these smallest of mammals is so very fast that they will die of hunger within two or three hours if the food supply fails. Since they feed exclusively on small, living animals, mostly insects, and demand, of these, considerably more than their own weight every day, they are most exacting charges.” (p.108)

Shrews are not tameable, because they are truly inseparable from their ecosystem. If you want to keep a shrew, you have to keep a whole ecosystem alive to feed it.

Asking the question of what it is like to be a shrew, is probably rather like asking the question of what it is like to be a digestive system that is able to propel itself on or in land or water. Shrews live to eat. They swim to eat, they burrow to eat, they scurry to eat, and in between doing all of these things, they eat.

It scares (but maybe also titillates?) me a little to invoke the character of Kate in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. She’s so intense, has so much energy, is so strong. No matter how many times I see or read the play, her shift to a position of apparent submission feels shocking. The complexity and potential ambiguity of her final speech spins in my head for days. I’m never able to be sure: has she happily flipped from ‘top’ to ‘bottom’ (as she always wanted to)? Is she slyly modeling how to obey without obeying? Is she fucking starving and scared shitless, essentially suffering from Stockholm syndrome?

In her 2004 book Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici makes a painstaking and credible case for European and Mesoamerican witch persecution as violent symbolic and actual repression of mass resistance to the rise of capitalist modes of production and social organization. Women led these struggles against land enclosures in England, Europe, and their colonies, and so witch hunts preyed particularly on older women in need of communally held resources, who were fighting most staunchly to retain them, and also targeted the sexuality of women of childbearing age (which needed controlling for the reproduction of a labor force). As she assembles her evidence in each locale and era, Federici identifies The Taming of the Shrew as the “manifesto of the age” for eviscerating the rights of women in the Elizabethan and Jacobean period (1558-1625) in England, though it is just one among many works of the time in which “the literary denigration of women expressed a precise political project aiming to strip them of any autonomy and social power” (p. 101).

My restless inability to accept any of the standard interpretations of shrew Kate’s final speech echoes my inability to settle comfortably onto any map towards the present that is encoded within the play: If Kate has genuinely acquiesced, then, following Federici’s logic, we have lost all notion of what a commons truly is. If Kate is playing a long game, a revolution is perpetually imminent. Instead, I root for Kate and Petruchio (and definitely Grumio) to be in tight collusion, holding a portal between the past and the present open with all of their might by mocking every kind of violence that the accumulation of resources relies on, undermining every necessary ingredient of ‘value’.

But instead of being able to definitively locate this portal, I’m trapped in the endlessly revolving door of accepted interpretations, unsure of whether to love or hate shrew Kate.

Shrews’ bodies make about 12 movements per second. They are practically seizing. All the time.

On account of their desperate need to feed, it is no surprise to find that shrews have myriad strategies for making their way in the world. Ethologist Dr. Björn M. Siemers, best known for his work with bats (and for whom the Acoustic and Functional Ecology Group of Max Planck Institute for Ornithology posthumously named their Bat Research Station in northeastern Bulgaria), took some time away from bats to explore the shrieks and snuffles of shrews before his death in 2014. In a study written up in the June 17, 2009 edition of The Royal Society’s Biology Letters, Siemers and team reported using “artificial shrews” (small speakers) to conclusively demonstrate that at least the two most populous species of shrews are subterranean echolocators. “We tested behaviourally whether the high-pitched laryngeal ‘twittering’ calls of as-yet unclear function serve for communication or echo-based orientation…. The data showed that shrew-like calls can indeed yield echo scenes useful for habitat assessment at close range, but beyond the range of the shrews’ vibrissae [whiskers].” (Abstract, retrieved June 4, 2021.)

I too am yielding echo scenes: moving beneath the surface of capitalist culture, carving out new spaces for myself and others and then assessing their capacity to hold us. I am listening, determining whether each is a space about to collapse in on itself—on me—or is a space where we can find true nourishment. There is constant rumbling above, but the tunneling proceeds.

Alongside their prodigious metabolism, Lorenz noticed something else unique about his shrews. Despite their theoretical need to conserve energy, Lorenz’ shrews rarely followed the most efficient paths available to them. Instead, they very predictably and doggedly followed what he identified as elaborate ‘path-habits.’ When a shrew first sets out, “(i)ts course,” he observed, “is determined by a hundred fortuitous factors. But after a few repetitions, it is evident that the shrew recognizes the locality in which it finds itself and that it repeats, with the utmost exactitude, the movements it performed the previous time.… Once the shrew is well settled in its path-habits it is as strictly bound to them as a railway engine to its tracks and is unable to deviate from them by even a few centimeters.” (pp. 122-3)

Lorenz’ describes (rather cruelly) experimenting with this by moving a rock out of his shrews’ pathway. Invariably, when they got to where the rock was supposed to be along their path, they leapt into the air to get over it. Whether it was there or not.

More things to know about shrews: they are legion! There are 385 known varieties of shrew on the planet. They can walk on water (using special hairs on their feet); some are venomous; others produce a skunk-like musk to mortify their predators. Shrew hearts beat faster than that of any other mammal on earth. And when young, they “caravan,” moving in a chain, each holding the other’s tail in their own mouths.

Is that enough? Haven’t we already made it clear that whatever else you might learn will make you understand less about us rather than more? We are everywhere, but we are not in your way. Leave us be in our water—skittering across or diving through its surface. Leave us underground, our blood pounding in our ears, our clicks and chirps reverberating to us about the comforts of our caverns. Not every resource can be corralled—neither logically nor economically. You cannot tame us: together, we trace pathways that you think you have erased. And our hearts beat. And our hearts beat.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.