Voyager ex voto

By:

February 3, 2013

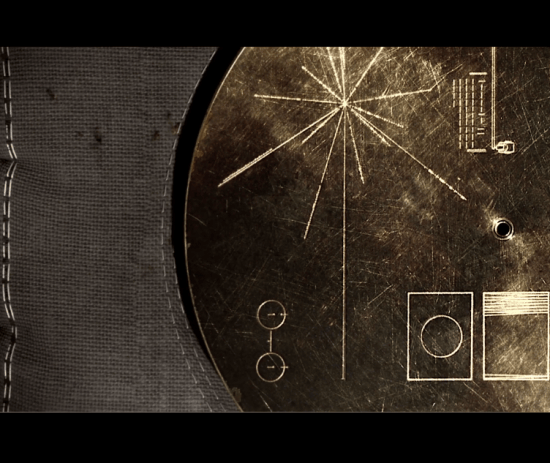

Remember the “golden records” made for the Voyager missions? These compendia of human, biological, and geological sounds and images, inscribed into gilt phonograph disks and covered with engraved plaques, were meant to chart our place in the galactic neighborhood and tell the story of life on earth. Any sufficiently-advanced civilization recovering one of the two Voyager probes in the reaches of outer space, it was supposed, would find the record, understand its purpose, and devise a means of playing it back.

The chances of any of this happening are, well, astronomical. Voyager 1 won’t pass within two light years of another star system for some 40,000 years. And in any case, the probes are already artifacts — objects with stories to tell — as this abstract for a poster session offered at the most recent meeting of the World Archaeology Conference argues: “the physical attributes of our spacecraft themselves convey a rich narrative about our civilization typically ignored in technical and academic considerations of extraterrestrial communication.” The poster session, entitled “The bottle as the message: Solar System escape trajectory artifacts,” was presented by Ben McGee and Colleen Beck, both of whom have published papers on the archaeology of the space age. Clearly referring to Voyager’s “golden record,” as well as to symbols and legends attached to sundry interplanetary gear over the last half century, the authors aver that “the informational value of the famed ‘messages in a bottle’— plaques and discs intended for future extraterrestrial communication — pale in comparison with the informational value of the bottle, the spacecraft itself.”

There is a peculiar quality in the Voyagers’ plaque and golden record — a compound of the Quixotic and the Ozymandian — which is deeply characteristic of science in the late twentieth century. Carl Sagan, who inspired and helped to design content for the project, admitted as much when he said, “the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet”— a hope which, however slim, was still vastly greater than the chance that one of the Voyagers would ever encounter life elsewhere. These messages in a bottle were among the more telling transmissions of a dialogue of wonder in which postwar science took part — a seeming attempt through science to inoculate creation from the destructive potentials made possible by science itself.

As McGee and Beck point out, the bottle — in this case, Voyager — is itself already an artifact, a thing put together by human hands, and bearing its maker’s unmistakeable traces. We’ve littered the solar system with such traces: ruined probes left on Mercury and Mars; the detritus of the Apollo missions. With the Voyager probes, our exoarchaeological traces now exceed the solar system’s footprint. Indeed, an archaeologist might properly interpret Voyager as a votive offering: the token of a wish to find ourselves companioned in the cosmos, offered to the void ex voto without expectation of return.

This artifactual perspective crops up in this fanciful animation recently released on Vimeo, depicting Voyager undergoing a cosmic apotheosis in some far-off system:

What strikes me about the video is its approach to the Voyager as object. Here, the probe even sports its insulative blanketing — a layer of thick, black, bespoke cloth roughly stitched to the exterior, with a cunning hemmed collar for the golden record. This detail surprised me, as it’s missing from available depictions of the probes; thanks to CGI, we see the careful stitching, the warp and weft scorched and felted by cosmic wear.

The Voyager in Stardust is worn, a tired traveler, in contrast to the pristine cluster of polygons in the iconic 1981 animations done for the Jet Propulsion Lab by Jim Bliss and Charles Kohlhase (which had such a profound impact at the time; I remember going to see them in a packed auditorium at the local state university). Now those animations look austere, low-bit, and uncanny compared to the digital verisimilitude to which we’ve grown accustomed. Of course, current CGI models the light-scattering properties of rough textures with a kind of insistent thoroughness not possible thirty years ago, when the probes were still arcing among the outer planets. But even back then, we boggled at the venerable migrants the Voyagers stood to become.

In Star Trek: the Motion Picture (1979), a Voyager probe is returned to us by alien others as the heart of a vast living machine. From its scarred and patinated nameplate, they have interpreted the artifact’s name as “V’ger,” which they found and retooled a mere couple of hundred years after the Voyagers’ late twentieth-century launch. “V’ger” was supposed to be Voyager 6, one in a lengthy line of missions to the stars; in reality, the program ended in 1977 after only two probes were launched. This prompts a question: what story will future xenoarchaeologists glean from our spacefaring artifacts? In the space age, we thought them the foundation stones of our future spacefaring civilization; increasingly, they seem like the moai of Easter Island — votive offerings, erected in desperate hope on the only shores we will ever know.

An expanded version of this post is available at Aeon Magazine.