The People of the Ruins (15)

By:

August 30, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fifteenth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘And I got this — look!’ Jeremy peered at something she held up to him, but could not make out what it was. She thrust it into his hand, and he felt a small round metal box, the size and shape of half an egg.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16

FLIGHT

The old man had not moved from the spot or the attitude in which Jeremy had left him. He still stood by the horses, holding the bridles, his head fallen forward on his chest.

“Don’t say anything to him,” Jeremy whispered hurriedly to the Lady Eva. “He’s… he’s strange.” She nodded in reply. Her father, however, took no notice of her, if he saw her, but only turned mutely to Jeremy as though awaiting orders. It then first occurred to Jeremy to ask himself what they ought to do next. The inhuman power which had sustained him so far and had given him supernatural gifts of foresight and decision, now without warning deserted him. He found himself again what he had been before, an honest, intelligent and courageous man, placed by fate in a situation which demanded much more of him than honesty, intelligence, or courage. He felt like the survivor of a midnight shipwreck who loses in a flurry of waves the plank to which he is clinging and is abandoned to the incalculable and hostile forces of darkness and the sea.

He turned to the girl and asked her advice; but she shook her head dumbly. She had followed him there as a child follows its guardian, without questioning him, accepting his wisdom and his will as though they had been the inalterable decrees of Providence. In despair he addressed the Speaker as he would have addressed him a week or even a day before, seeking to learn if there was any well-affected magnate in whose house they could find refuge.

A change became visible on the old man’s face. He seemed to be struggling to think and to speak, and in his eagerness he sawed the air with his disengaged hand. At last he ejaculated in a strange, hoarse voice, produced with effort, which jerked from fast to slow and from the lowest note to the highest, as though he, had no control over it:

“Can’t make peace with the President now — can’t give him up the Chairman alive. Thomas Wells took the Chairman prisoner and cut his throat.” Then he added with a sort of dreadful reflectiveness: “Thomas Wells always did say that he believed in making sure.” And so, having delivered what was perhaps his ultimate pronouncement on statecraft, he resumed his former position, motionless, except that now and then a violent fit of shivering shook him from head to foot. Behind the little group the houses in Piccadilly burned up higher and painted lurid colors on the sky, and away on the other side of the Treasury a great fountain of golden sparks, dancing and gyrating, showed that one of the houses on the Embankment, apparently Henry Watkins’ house, had now been fired. But in the garden the shadows only wavered and flickered feebly, and the noise of the flames, and of the looting of fleeing crowds, came incredibly thin and gentle. Jeremy and Eva and the Speaker seemed in this obscurity to have been sheltered away from the violence of the world in a little haven of miraculous calm, the walls of which, however, were yet as tenuous and unstable as those of a soap-bubble.

Jeremy pondered again, while his companions silently and expectantly regarded him. After a minute he said in a very gentle tone: “Eva, I know so little… if we could get down to the coast, do you think we could find a boat to take us over to France?”

“I think so,” she replied doubtfully. “I know that there are boats that go to France, of course. But what shall we do when we get there?”

“I don’t know. I shall find some way of looking after you. But anyway, we must do that because there’s nothing else for us to do, unless we give ourselves up.”

“I won’t be taken by Thomas Wells,” she said, with a catch in her voice.

Jeremy set his teeth hard to keep back his exclamation. “We’ll do that,” he assured her firmly. “But first of all we must go back to the house and get things to take with us.”

They found their way in silence through the gardens, Jeremy leading one horse and the Speaker the other and Eva walking by Jeremy, holding his free hand. They searched the stables first, and there, to their delight, found two fresh horses, strong, ugly beasts, not elegant enough for the Speaker’s carriage or to go with the army, but very suitable for such a journey as was now proposed. They also found a lantern which Jeremy took with him into the Treasury. He returned after a while with a supply of bread and meat and some clothes. Then they went as quietly as possible around to the courtyard, there to make their preparations.

Eva helped Jeremy to pack the saddle-bags, while he explained his intentions to her. The coast round the mouth of the Thames, he thought, and probably as far as Dover, would be overrun at once by the Welsh invaders, and it would be fatal for them to go in that direction. He therefore proposed to double west, strike across Sussex, and make for one of the Channel ports there or farther on in Hampshire. He thought that he could find his way, and that if they made haste they would escape pursuit. His plans beyond that were of the vaguest: he supposed that in the end he could put his mechanical knowledge to some use. Perhaps later on they might even return to England, if the country remained unsettled, and assert the Speaker’s claims against the usurpers. As he uttered this cloudy fragment of comfort he thought of the wandering Stuarts and chuckled to himself, sourly but half-hysterically, at finding himself in so romantic a situation.

Meanwhile the Speaker sat crouched, where Jeremy had placed him, on an old mounting-stone in the courtyard, muttering continuously under his breath. When all was ready for their departure, Jeremy went over to him, arranged a cloak to hide his conspicuous face and beard, and put a hand under his arm to raise him up. The old man stiffly acquiesced, still mumbling.

“What did you say, sir?” Jeremy asked gently.

“Thomas Wells always did say that he believed in making sure,” the Speaker repeated with a terrifying evenness of intonation.

Jeremy twisted his shoulders impatiently, as though to shake off an evil omen, and led the stooping figure over to where the horses stood ready. The noise of the rioting and plundering came to them more distinctly here in the courtyard; but Whitehall itself was strangely quiet, as though the frenzied crowds had left the Treasury untouched in order to placate the fast-approaching invaders who were to be its new tenants and their new masters.

Jeremy had just seated Eva on one horse and the Speaker on the other and was preparing to lead them out, when they heard the clatter of hoofs coming furiously down Whitehall, rising loud and clear above the confused sounds that filled the air. There was something arresting, sinister, and purposeful in that sharp, staccato sound, and, as if by instinct, they drew together in the dark entrance to the courtyard, while Jeremy hastily blew out the lantern. Then the rider reached them, drew rein, and halted a yard or two away from them, peering into the shadow. They could see him only as a vague shape, thickly cloaked and muffled, while behind him in the distance little figures hurried aimlessly into or out of the dull glow of Henry Watkins’ house. Jeremy put one hand on Eva’s arm lest she should make a rash gesture, while with the other he grasped firmly the barrel of one of his pistols.

The horseman continued to stare at them without moving, as though uncertain whether what he saw in the gate was shadow or substance. But suddenly the flames opposite shot up higher and brighter and cast a red dancing reflection on their faces; and Jeremy felt like a fugitive whose hiding-place is unmasked. The horseman spoke at last, and Jeremy recognized with a shudder the calm drawling voice.

“Well, who are you?” he said. “What do you mean by looting here?” Jeremy clutched the girl’s arm more tightly and made no reply, hoping that in the doubtful light they might still pass for stray fugitives. But the man urged his horse a little nearer, leaning over to look at them, and saying: “Speak up! It’ll be the worse for you if you don’t. I’m looking for the Lady Eva. Have you seen —” And then as he leant still closer, in astonishment, “By God!” Jeremy brought round his arm like a man throwing a stone and dashed the pistol-butt heavily in Thomas Wells’s face.

The Canadian uttered a choked cry, sagged forward on his horse’s neck, and slid free to the ground on the other side. Jeremy fumbled for the bayonet which he still carried with him; but Eva plucked agonizedly at his shoulder, crying: “Jeremy! Jeremy, come!” He hesitated a moment and heard a louder sound of galloping hoofs approaching. Then he jumped into Thomas Wells’s empty saddle, turned the horse and rode out into Whitehall, drawing the girl and the old man after him. A few minutes later they were fighting their way through the thickening crowd of fugitives that still poured southwards over Westminster Bridge.

When day broke they were well clear of the southern edge of London, and a little later they were crossing the broad ridge of the North Downs. They had made a dizzy pace during the short night, and Jeremy, who was no horsemaster, but knew that the horses must be nearly finished, called a halt and suggested that they should rest a little in a small grove which lay on the southern slope of the hill.

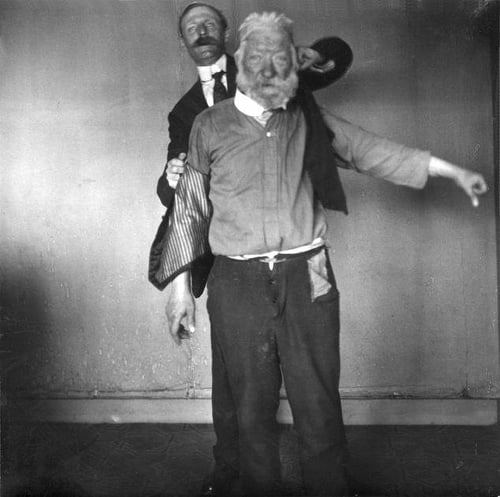

The old man, who was calm and indifferent again, and had ceased his muttering, rested his back against the trunk of a tree, his arms falling ungainly like the arms of a broken doll. He shivered violently at intervals, but still did not complain: he had not once spoken to his companions since their journey began. Jeremy after a doubtful glance at him, walked to the lower edge of the grove, and the girl followed him, treading noiselessly on the soft pine-needles. While he stared vaguely out over the misty chequer-board of the Weald, he felt her hand placed in his and dared not turn to look at her.

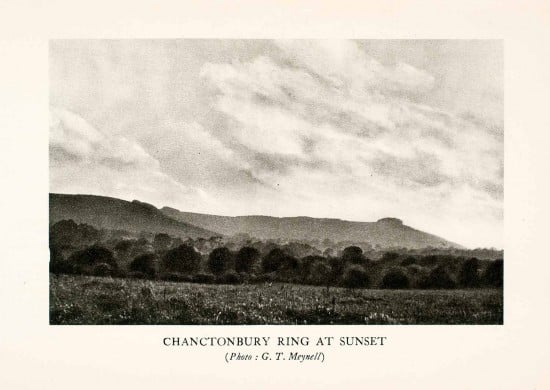

Presently, mastering himself, he cried: “Look, there’s Chanctonbury!” For the mist had just rolled off that far and noble grove, showing it perhaps a little larger than he remembered it, but in every other respect the same. Then he added: “Go and sleep, Eva, while I keep an eye on the road.” But he spoke without force, because he did not wish her to leave him alone, he did not wish to sacrifice these few quiet minutes with her.

“I can’t sleep,” she said. “I can’t sleep again till we are safe. It won’t be long now, will it?”

He shook his head and smiled as confidently as he could.

“I mean, it won’t be long… one way or the other,” she went on, dragging out the words and keeping her eyes with difficulty on his.

As they traveled on, through the tumbled slope of the downs and out into the flat country, a sort of quietude, a rigidity of expectation, descended on the little party. There had been so far no sign that they were pursued or that the wave of invasion was extending this way; and Jeremy began to believe that they had escaped from their enemies. But the news of fatal changes in the kingdom had gone before them. The sight of strange travelers on the road was alarming to the workers in the fields. Once, when they would have stopped a rustic hobbledehoy to ask their way, he ran from them, screaming to unseen companions that the Welsh had come to burn the village. Once they found the gates of a great park barricaded as if for a siege, and behind it two or three old men with shotguns who warned them fiercely away. The whole country, as yet untouched by that menacing hand, was in a state of shrinking preparation and alarm.

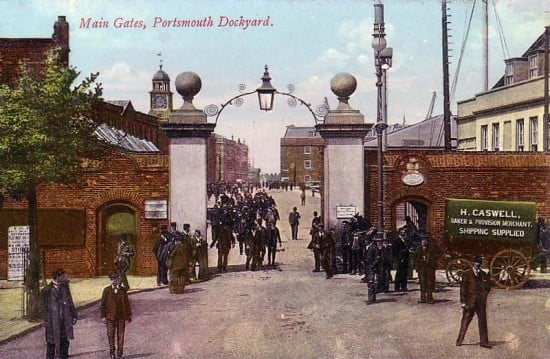

But they husbanded their provision and went on, independent of all help, striking towards the distant line of hills, which once crossed they would be able to find their way to the coast. From Portsmouth, Jeremy learnt, an inlet now silted up and almost negligible, the smugglers were said to cross to France and back; and a not unusual item in their freight was criminals escaping from justice. So at least Eva had gathered from the stories that used to drift about the Treasury, starting perhaps from some clerk concerned with the prevention or the overseeing of this abuse. Jeremy steered their course there for a little to the west, and trusted to heaven to see them straight to their goal.

Their progress was slow and fretted him, so that at first it was necessary for Eva to calm and console him two or three times in every hour. The Speaker, who had still not awakened from his dream, was manifestly very ill and sometimes kept his seat in the saddle with difficulty. His breath had grown short and stentorous; and he had fits in which he fought for air, while his face became black and the veins in his neck and temples congested. During the worst of these they had to stop and let him rest by the road-side, while Eva loosened his garments, bathed his forehead with water from the nearest ditch, and murmured over him the tender words of a mother over a child. At these times Jeremy would stride away, biting his lip and clenching his hands, muttering that every care Eva lavished on her father was a moment lost in the race for her safety. But before he had gone many yards in his indignation he would ask himself how much anxiety for himself and for his own future happiness with her had done to provoke this fury. Even while his brow was drawn and his lips were still muttering, some independent voice in his brain would be pronouncing judgment on his unworthy weakness and sending him back, quivering with self-restraint, to offer Eva, ungraciously but sincerely, what help he could.

Then she would smile up at him divinely, diverting to him for a moment the flood of loving pity she had poured on her outworn and helpless father. It seemed to him that she, who was the most terribly threatened of the three, stood most aloof, most untouched of all of them, from the cruel things of the world, a person infinitely wise and compassionate, who would comprehend at once the causes of his gusts of passion as well as their futility.

The country-side appeared to be, as Jeremy had indeed expected to see it, greener and richer and fuller than he had ever known it. The crops far and wide were already approaching maturity and promised a full harvest. The woods covered a greater space, but were better cared for; and everywhere men were working in them, tending them, felling trees, or burning charcoal. There seemed to be fewer enclosed fields of grass, while the open commons had grown, and now maintained sheep and cows, goats and geese, herded by ragged and dirty little boys and girls. Even on this journey Jeremy could not help watching curiously all they passed and noting the contrast with his own day, and he saw this rich and idyllic country with something of a constriction at the heart. Apparently in the mad turmoil of the Troubles, while lunatics had fought and destroyed one another, the best of the English had managed to stretch out a hand and take back a little of what had been their own and to restore a little of what had been best in England. And now… Jeremy wished they could have passed through one of the larger country towns to observe its reviving prosperity, but they dared not, and skirted Horsham as widely as the roads would allow them. In the villages there seemed to be a more vigorous life but less civilization. Still, here and there, on ancient houses hung metal plates from which the enamel was not yet all gone, advertising some long-vanished commodity, or announcing that it was so many miles to somewhere else. But the old buildings tottered and flaked away even as Jeremy looked at them; and the new population was sheltered in hideous and rickety barns.

But all this progress through the Weald had the uneven quality of a dream, in which at one moment events are hurried together with inconceivable rapidity, while at another they are drawn out as though to make a thin pattern over the waste spaces of eternity. Sometimes Jeremy rode impatiently a yard or two in front of his companions, eaten up by a burning passion for haste, sometimes with them, or behind them, dull, patient, resigned, uninterested. When he looked at the Lady Eva with anxious or with pathetic eyes, he saw her still serene and controlled. On the first night after their escape they had covered only a little more than half of the distance to the hills, when weariness forced them to stop and rest in a wood not far from Slinfold. From the edge of the wood they could see the village, where one light still burned, perhaps that of the inn; and some desire for company made them rest in a spot where they could keep it in view. At first it was an intense and brilliant point in the soft, melting dusk and later, as the darkness grew complete, the only real thing in a country that had become mysterious and intangible.

Jeremy had wished to go on into the village and find a lodging there, so that the old man might be made comfortable at least during the night. But on reflection he decided that the fewer witnesses they left behind of their passage across the country the greater would be their chances of safety. It was not impossible that Thomas Wells or the President should send out scouting-parties after them; and the Speaker was a noticeable man. He therefore announced, as the leader from whose decision there was no appeal, that they would sleep in the open; and Eva, gravely nodding, acquiesced. They made a bed for the Speaker of dry leaves, such as still lay under the trees, and the saddlecloths, and disposed him on it. He was for once breathing easily and quietly, and obeyed them like a very young child. But no sooner was he asleep than his day-long silence and passivity gave way to a restless muttering and gesturing. Jeremy, bending over him, could distinguish nothing in the torrent of words that came blurred and jumbled from the blackened lips; but he recognized in the rise and fall of the voice a horrible likeness to those long and furious tirades on the future of England, of which he had been the recipient during his days in the workshops.

He covered up the Speaker with a shuddering tenderness, left him, and came back to Eva, who had settled herself with her back against a tree. As soon as he sat down at her side she slipped wearily into his arms and, looking up at him, said softly, “We love one another, Jeremy”— not an appeal or a protestation, but a simple statement of fact, of the last certitude which remained unassailable in this moving and deceitful world. She said nothing more before she fell asleep with her head on his shoulder; and in a little while in this cramped and uncomfortable position he too slept.

The next day they pressed on again; but they had not gone many miles before it became obvious that the Speaker was much worse, was in a high fever and was growing delirious. His eyes shone brilliantly and seemed to have increased in size and his cheeks were flushed with a deep red. Once, when from exhaustion and misery they had for a moment ceased to watch him and to hold him in his saddle, he checked his horse, slid off and made unsteadily for a wood which lay some distance on one side of their way. Jeremy had to dismount, go after him, and drag him back to the road by force. Now for the first time he began to speak aloud and intelligibly, to rave of what he intended to do for England, how he would strengthen her government and renew her civilization, how he would teach the people their ancient arts and make them again the most powerful in the world.

By this time Jeremy, persevering mutely and patiently, was conscious of the old man only as an intolerable burden on their flight. He even revolved plans of letting him escape or leaving him by the roadside, arguing furiously in his mind that to drag along with him a man so obviously past saving, a man who, at the best, all disasters aside, was anyway without doubt at the end of his life, was inviting destruction for himself and Eva, who were young and vigorous and hopeful, and had all their life and their love before them. But he knew very well that he could make no connection between his logic and the reality. He sometimes caressed the girl’s shoulder with a clumsy gesture and she smiled at him in reply. All through that day hardly a word passed between them which was not necessary. To all appearance their only link might have been the ancient and insensible being with whose safety they were charged. But in their silent union to serve this end, in the accord moved and ratified by a look or a lifted finger, Jeremy recognized and was exalted by the inevitability, the invincibility of the bond that held them. Somehow he had been launched flying at random through the centuries and had fallen at the side of this one woman. Life might do with them what chance directed; but they had met, and out of that meeting had arisen their love, which was a stable and eternal thing, which he felt to be unmoved even in these death-throes of a world.

Amidst such delays they did not come until nightfall to the road which runs along the foot of the Downs, and at which Jeremy had been aiming. Just as they entered it from a deeply-rutted side-track, the old man uttered a heart-rending sound and collapsed on the neck of his horse in the worst crisis he had yet suffered. Jeremy reined in and stopped, his brow contracted, his heart sinking as he realized that it was impossible to push on. Then with a sigh he dismounted, and lifted the Speaker to the ground. As he did so it seemed to him that in this short time the old man’s great bulk had wasted and grown frail, so that his body was no heavier than that of a child. Eva too dismounted, and, bending over her father, attempted to restore him, but without effect. It seemed every moment that his loud and labored breathing must cease from sheer inability to overcome the impediment that hung on it. His delirium had passed into a pitiful and not peaceful stupor; and Jeremy began to believe that death was at hand.

He contemplated the fact without emotion; but Eva grew agitated, caught him by the hand, and cried, “What shall we do? What can we do?” And then, before he could reply, she went on, “Look, there are some houses in front of us: we must be coming into a village. Let’s try to get a lodging, whatever the risk may be. He mustn’t die like this by the roadside.”

Jeremy stood up and gazed where she pointed. A few houses were dotted among the trees, and lights flickered here and there. For a moment he was balanced between protest and consent.

“Very well,” he said in a level tired voice, “I’ll go on, and see what sort of a place it is. Will you not be afraid to be alone with him till I come back?” She shook her head, and he set off.

As soon as he entered the tiny village, dogs ran out from the yards, barking and snapping at his heels. He kept them off with his riding-whip, and stumbled along looking for the inn. Vague thick-set shapes lurched past him on heavy feet, and vanished here and there. Presently, after he had tripped over a rut and fallen headlong into a heap of evil-smelling refuse, he came upon a little ramshackle hovel which seemed, from the noise of conviviality issuing through the half-open door, to be what he sought. He paused outside for a moment, brushing the filth from his garments and listening.

Inside, the worthies of the village were rejoicing after the day’s work. Jeremy could hear the slow, long drawn-out sound of Sussex talk, not changed by a couple of centuries (or rather thrown back by that interval into the peculiarity it had at one time seemed likely to lose) and the noise of liquor being poured and of pots being scraped on a table. Then a voice was raised in song, and all the laborers joined it, roaring and shouting in unison. Jeremy’s momentary hesitation lengthened, continued, grew timeless… His tired brain was going round, the dark scene about him was melting and being built up again. He forgot why he was there or whence he had come. He could only remember, vaguely struggling still to realize that this was not it, one particular night, very black and wretched, when they had been hauling up the guns in preparation for the opening of the Battle of the Somme, and all the men of the battery had sung in chorus to keep themselves cheerful. This was like a shadow-show in which he could not tell the real from the fictitious. Who and where was he? Who was singing that familiar, that haunting or haunted melody? Was it those old comrades of the German wars who had suffered with him in the Salient, and at Arras, and by Albert, or could it be…? He could not hear the words until at last they came to him clearly in the emphasis of the last repetition, as the laborers shouted together:

Pack up my troubles in some owekyebow

And smile, smile, smile!

The recognition of the garbled words, the subtly altered tune, shot him back at once from that middle world of fantastic unreality to the immediate problem, the flight, the Speaker fighting to get his breath a few hundred yards down the road. His first start of surprise had carried his hand to the latch and he pushed the door open, and went into the low, brick-floored, reeking parlor.

His entrance produced an immediate hush. Pots were arrested half-way to thirsty mouths and every eye stared roundly at him. It seemed to him too that there was a slight involuntary shrinking away from him among all these hearty, earth-stained men, but he was too weary to do more than receive the impression without curiosity as to its meaning, without more than a flickering and uninterested recollection of the fact that he was unarmed. But immediately a relaxation succeeded the hush and the inn-keeper pushed forward, saying.

“Why, I did think as how you was one of them Welshmen come back again!”

This speech was to Jeremy as though a dagger of ice had been driven into his heart, and the room swayed round him. But he betrayed no trouble in his expression, took a firm grip on his mind and laughed with the inn-keeper at the idea. All the rustics joined in his laughter, nudged one another, went forward with their interrupted drinking, and murmured,

“That’s a good’un!”

When the merriment had a little subsided, he asked as casually as he could manage whether the Welshmen had been there that day. All at once began to tell him how a party of soldiers speaking a strange, hardly recognizable tongue, had entered the village early in the morning. Their leader, who could just make himself understood in the eastern speech, had held an inquisition and had terrified the inhabitants almost out of their wits. They had also emptied a barrel of beer, and made off with a sucking-pig and a good many fowls before riding away. The villagers, it seemed, had been too much concerned in keeping out of their way to be certain what direction they had taken; but Jeremy gathered that they had scattered, some going towards Houghton Bridge, some towards Pulborough, some towards Duncton.

“Too bad,” said Jeremy sympathetically, his wits working at high speed and warning him to be cautious. “What do you suppose they were looking for?”

“Some tale about an old man and a young man and a young woman,” the inn-keeper grumbled. Jeremy nodded negligently in reply, and the inn-keeper went on, “And what might you be wanting yourself?”

Jeremy explained that he had been unexpectedly overtaken by darkness on the way to Arundel, and that he was looking for a bed. A friend, he said, was waiting just outside the village for his report: anything would do, he added, desiring to be plausible. He and his friend were easily served and used to roughing it: a truss of hay in a loft or a corner in a shed under a cart would be enough for them.

“We can do that for ‘ee,” replied the inn-keeper hospitably, and Jeremy, thanking him, said that he would fetch his friend and return at once. When they returned, he observed, as he slid through the door, he hoped the whole company would still be there to drink to their health. He left the inn a popular and unsuspected person. But when he was a few yards away from it he began to run, and he blundered desperately through the darkness till he came to Eva and her father, the old man still lying prone, the girl crouched by his side under the hedge.

“Eva —” he began, panting.

“Have you found a place, Jeremy?” she cried anxiously. “I think we could get him there now. His breathing’s easier, and —”

Jeremy took her by the shoulder and spoke calmly. “Listen,” he said. “We can’t go into that village or any other. There’s been a party of the President’s men there to-day looking for us, and they’re still about somewhere.”

She turned her shadowed face up to him and listened attentively without opening her lips. “There’s only one thing we can do,” he went on with the same coolness. “We must get up at once on to the downs and leave the horses here. I used to know them pretty well and we ought to have something like a chance of hiding there if they chase us. We can crawl right along, never getting far from cover and only just crossing roads, till we’re near Portsmouth. There’s no help for it, Eva. They’re looking for us: you know what that means.”

For a moment it seemed that she would rebel; and then she bowed her head and put her hand in his. “Very well,” she said in a quiet voice. “We must do as you think best.” Jeremy had the impression that, from some divine and inconceivable height, she was humoring his childish attachment to this bauble of her life. Instinctively he took her in his arms and kissed her and felt the passionate response of her whole body. In the next second they were again practical and cold, taking from the saddle-bags and hanging about them such of their store of food as still remained. Then they lifted the Speaker between them and found that there was just enough strength left in his limbs to carry him along if he was strongly supported on both sides. A few yards away from them a narrow track, trodden in the chalk, glimmered faintly; and they turned into it, making a slow and labored progress up the side of the hill.

* Chanctonbury: Chanctonbury Ring is a circle of beech trees marking the former site of an iron age fort atop Chanctonbury Hill on the South Downs, in the county of West Sussex. It looks across the Weald (an area situated between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs) to the north. In most digitized versions of The People of the Ruins, the name is misspelled Chanetonbury. PS: The Weald also features in Arthur Conan Doyle’s science fiction novel The Poison Belt.

* “Pack up my troubles in some owekyebow”: “Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag, and Smile, Smile, Smile” is a World War I marching song.

NEXT WEEK: “Thus they waited without moving, they did not know how long, while the trackers advanced, vanished in a fold of the ground, began to emerge again. Then one of them uttered a harsh piercing view-halloo, that echoed horribly through the empty fields and sky; and in the next moment Jeremy felt Eva’s hand tighten on his convulsively and then a weight behind it, dragging it back.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.