The People of the Ruins (3)

By:

June 7, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the third installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “The next moment the bomb landed, thrown well out in the middle of the cellar, and it seemed that a flying piece spun viciously through his hair. And then he saw the table which held the glowing vacuum-tube slowly tilting towards him and all the apparatus sliding to the floor, and at the same moment he became aware that the cellar-roof was descending on his head.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

A WORLD GROWN STRANGE

When Jeremy awoke at last it was to find only the change from darkness of the mind to darkness of the eyes. No dreams had stirred his sleep with memories or premonitions. At one moment that great engine had still been implacably and regularly revolving. At the next it slackened and stopped; and, without any transition, he found himself prone, staring into the blackness as he had hopelessly stared when he saw the cellar-roof coming down upon him. He felt no pain, nor was there any singing or dizziness in his head. There was only a sort of blankness, in which he had hardly begun to wonder where he was. He assumed for a moment that he was in his own bed and in his own flat. But two things persuaded him that he was not. He had been awakened by something soft and damp falling on his eyes, and when he tried to brush it away he found that he could not use his arms. Then he remembered.

But the memory brought for the moment a panic that made him dizzy. The bomb had been thrown, the roof had fallen, and, from then till now, there had been only darkness. What more certain than that in that catastrophe, which he now so clearly recalled, his back had been broken, so that he lay there with no more than an hour or two to live? The absence of pain made it only the more terrible, for had he been in agony he might have welcomed death, which now would approach, unmasked, in the most hateful aspect. He made a convulsive movement with his body, which showed him that he was held all along his length, and confirmed his fears. But, in the calmness of despair which followed, he became conscious that the air he was breathing was exceedingly close. Then he realized with a relief that again made him giddy that his back was not broken, but that he was unable to move because he was in some way pinned under the ruins of Trehanoc’s crazy warehouse. He made a renewed effort to stir his body; and this time he was rewarded by an inch of difficult motion in each limb.

Fortified by this assurance, he lay still for a few seconds, and tried to make out his position. He was held tight at every point, but he was not crushed. Neither was he suffocated, nor, as it seemed, in any immediate danger of it. In these circumstances, to be buried alive was a comparatively small evil; it would be odd if he could not somehow dig himself out. The problem was merely how to do so with the least danger of dislodging the still unstable débris above him and so putting himself in a worse position than before. Apparently the ruins had formed a very constricted vault fitting closely to his body and raised a little over his face, where they seemed to admit the passage of air. It was obvious that his first step was to clear his face so that he might see what he was doing. But to do this he needed a free arm, and he could not move either of his arms more than an inch or two. Nevertheless he set to work to move his right arm to and fro in the cramped space that was possible.

The result delighted him. The roof of his grave was some hard substance, probably wood, so a splinter informed him; and he remembered the table under which he had crawled just in time. It must have buckled, so as to make a shield for him; and now, though he could not pick it away, it yielded — an infinitesimal distance at a time, but still it yielded. Presently, he was able to crook his elbow, and soon after that to draw his hand up to his face. Then he began to remove the roof which hung an inch or two from his eyes. The process was unpleasant, for as he plucked at the roof it crumbled between his fingers, and he was not able to protect his face from the dust that fell on it. In the darkness he could not trust his sense of touch, but otherwise he would have sworn that, with pieces of wood, which he expected, he was tearing up and pushing away damp clods of grass-grown earth. He had to keep his eyes closed while he worked. After a little while, when he judged that he had made an opening, he laboriously brushed his face clear of dust, opened his eyes, and looked anxiously up. There was darkness above him still, and a cool breath passed over his forehead. It was night. A single star hung motionless in the field of his vision.

A little exhausted by his efforts, Jeremy let his head sink down again, and reflected. Clearly the whole warehouse had come down with a surprising completeness, since he was able to look straight up into the sky. And there was another thing that engaged his attention, though he had not noticed it until now. His ears were quite free and his head lay at last in the open, but still he could hear nothing. Considering the circumstances in which he had been buried, he would certainly have expected to hear something going on. If there were not shots, there should at least have been shouting, movement, noise of some kind — any noise, he thought suddenly, rather than this uncanny, unbroken silence. But there was only a gentle, hardly perceptible rustling, like leaves in the wind… the old lime tree in the court he decided at last, which had escaped when the warehouse had fallen. He grew almost sentimental in thinking about it. He had looked at it with pleasure on that fatal day, leaning from the window, with Maclan and Trehanoc behind him; and now MacIan and Trehanoc were done for; he and the lime tree remained….

The fighting, he supposed eventually, when his thoughts returned to the strange silence, must have been brought to an end in some very decided and effective manner. Perhaps the troops had got the upper hand over the rioters, and had used it so as to suppress even a whisper of resistance. “Peace reigns in Warsaw,” he quoted grimly to himself. But this explanation hardly satisfied him, and in a spasm of curiosity he renewed the effort to free himself from his grave.

When he did so, he made the discovery that the roof of his vault was now so far lifted that he might have drawn himself out, but for something that was gripping at his left ankle. He could kick his leg an inch or so further down, but he could not by any exertion pull it further out. Here a new panic overcame him. What might not happen to him, thus pinned and helpless, on such a night as this? The fighting seemed to have gone over, but it might return. The men who had killed Trehanoc and Maclan and had thrown a bomb at him might come this way again. Something might set fire to the ruins of the warehouse above him. The troops passing by might see him, take him for a rioter, and bomb or bayonet him on general principles of making all sure. As these thoughts passed through his mind he struggled furiously, and did not cease until his whole body was aching, sweat was running down his face, and his ankle was painfully bruised by the vise which held it. Then he lay panting for some minutes, like a wild animal in a trap, and in as desperate a state of mind.

But again the coolness of despair came to save him. He perceived that he had no hope save in lifting the heavy and solid timbers of the table which had closed about him. Only in this way could he see what it was that held his ankle; and, hopeless as it seemed, he must set about it. The effort was easier, and he was able to work more methodically than when he had given himself up for lost. But there was only an inch or two for leverage; and his labors continued, as it seemed to him, during fruitless hours. Certainly the small patch of sky which was visible to him had begun to grow pale, and the one star had wavered and gone out before he felt any result. Then, suddenly, without warning, the table top heaved up a good foot under his pressure and seemed much looser. He breathlessly urged his advantage, while the fabric of his grave shook and creaked reluctantly. He shoved once more with the last of his strength, and the coffin lid lifted bodily, and the invisible fetter on his ankle, with a last tweak, released it. He lay back again, fighting for breath, half in exhaustion, half in hysteria. He was free.

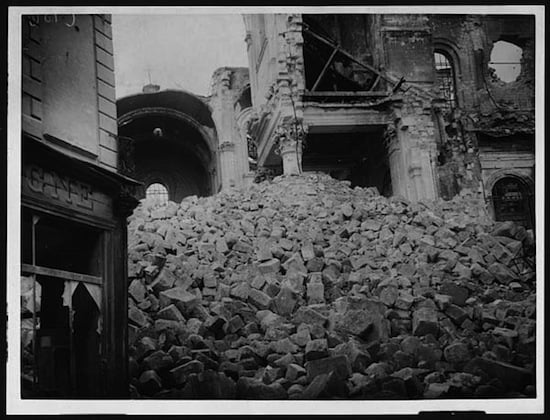

When at last he was a little recovered he drew himself gingerly out, looking anxiously into the vault lest it should close again and pin him. But when he knelt on the edge of the hole from which he had safely emerged, he paused in a frozen rigidity. The dawn was just breaking, and there was a little mist, with strange and unnatural shadows. In Whitechapel, as Jeremy knew it, dawn was usually apt to seem a little tarnished and cheerless. That neighborhood always seemed to him a more agreeable object for study when its inhabitants were hurrying about their business than when they were waking and first opening their doors. But this morning, as he knelt in an involuntary attitude of thanksgiving on the edge of his grave, Jeremy did not see Whitechapel at all, because it was not there. It had vanished overnight.

He was kneeling on short grass, and the crevice in the earth from which he had crept lay towards one end of a shallow depression, enclosed by low grassy banks. A young poplar in the middle of it moved its leaves delicately in the faint wind. All round were meadows of irregular and broken surface, with a few sheep grazing in them, and here and there patches of bramble and wild thorn. Farther off Jeremy could distinguish small groves of trees and the dark outlines of low houses or sheds. Farther off still he saw, black and jagged against the rising sun, something that resembled the tumbled ruins of a great public building. He turned giddy and could not rise from his knees. His muscles refused their service, though it seemed that he strained at them with all his strength, until his stomach revolted and he was seized with a dreadful nausea, which shook him physically and brought a sick taste into his mouth. He found himself looking down at his grave as though he wanted to crawl back into it; and then suddenly an inexplicable horror and despair overcame him, and he flung himself face downwards in the dew-laden grass.

What were Jeremy’s thoughts while he lay face down in the grass he could not himself have told. They were not articulate, consecutive thoughts. The landscape that he had seen on emerging from his grave had pressed him back into the shapeless abysms that lie behind reason and language. But, when the fit had passed, when he raised his head again, and saw that nothing had changed, that he was indeed in this unfamiliar country, he would have given a world to be able to accept the evidence of his eyes without incurring an immediate self-accusation of folly.

The transition from the image in his mind to the image which his eyes gave him had been so violent and so abrupt that it had wrenched up all his ordinary means of thought, and set his mind wildly adrift. During a moment he would not have been surprised to hear the Last Trump, to see the visible world go up in flame, and the Court of Judgment assembled in the sky. He told himself that the next instant Maclan and Trehanoc might step from behind the nearest clump of thorn and greet him. But the new landscape continued stable and definite, as unlike the scene of an Apocalypse as the creation of a dream. Could this then be an hallucination of unusual completeness? And, if so, had those dreadful hours during which he had struggled in his tomb been also the result of an hallucination? He stooped absent-mindedly to the low grassy bank by which he was standing and plucked a confidently promenading snail from a plantain leaf. The creature hastily drew in its horns and retracted its body within the shell. Was that, too, delusion?

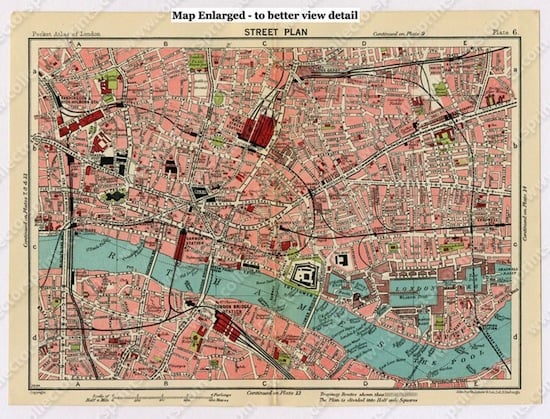

And yet, the day before, he had been in Trehanoc’s warehouse in Lime Court in Whitechapel, there had been that sudden violence, and, as he still clearly remembered, he had crawled under the laboratory table before the cellar roof had fallen on him. While he had struggled through the night to free himself, a picture of the place had been perfectly distinct in his mind. On emerging he had turned without reflection to where he knew the door of the cellar stood. The table which had saved him had been at one end of the cellar, parallel to the shorter wall. Jeremy went back to his crevice and stood beside it. It lay in a depression which was roughly four-sided, and it was parallel to the shorter pair of sides. Jeremy bit his lips and looked about him vaguely. Over there should have been the cellar steps, and, going up them, one came to the front door… just over there… and beyond the front door there had been the flags of Lime Court. Jeremy followed this imaginary path with the absorbed care and exactitude which were his means of keeping in touch with reason. Where the flag-stones should have been there was now soft turf, dotted here and there with the droppings of sheep. And suddenly Jeremy saw a patch where something had rubbed away the turf and stone protruded… .

He stood above it, legs wide apart, teeth clenched, and hands gripped. He felt like a man whom a torrent carries down a dark cleft towards something he dares not conjecture. But when this fit, too, had passed away he felt nothing more acutely than the desire to be able to believe. Presently, as he stood and wrestled with himself, his scientific training and cast of mind came to his help. It was legitimate to form a hypothesis, provided that it accounted for all the facts and made no more assumptions than were necessary in order to do so. Illuminated by this thought, he took a few steps back to his crevice, sat down, grasped his jaw firmly between his hands, and began to enquire what hypothesis would be most suitable. That of an hallucination he immediately dismissed. It might be the true explanation; but as a working basis it led nowhere and required no thought. If he was living amid illusory shows the country round him might change at any moment to a desert or an ice-floe… or he might find himself pursued by snakes with three heads.

Well… The alternative theory assumed that the spot on which he now sat was the same which had formerly been occupied by Trehanoc’s warehouse. His observations underground prior to his delivery, the shape of the depression, and the flag-stone where Lime Court should have been, all supported this assumption. In that case it followed irrefragably that he could not have been knocked on the head on the previous day. He must have been in that grave, covered by the table, and the rubble, and the turf for a considerable time. It therefore remained only to estimate a period sufficient for the changes he now observed to have taken place.

It was perhaps just as well that Jeremy had steadied his mind by exercising it in a mode of thought to which it was accustomed: for when he reached this point and looked round enquiringly at the material evidence his head began to whirl again. There was, in particular, a young poplar, about ten or twelve feet high, standing in the middle of the hollow…. Jeremy rose, went to it, and slapped the bole reflectively. It was still young enough to reply by a more agitated rustling of its leaves. Here was the problem compactly put. What was the shortest possible time in which the tree could have attained this growth?

If Jeremy knew that he would also indisputably know the shortest possible time he could have been underground. It was true that his estimate might still be too small by many years. He suspected that most of the much taller trees he could see round him at a greater distance must have been sown since the change; but still with the poplar he would have reached a firm minimum basis. Unfortunately, Jeremy did not know the answer to the question. He was not a botanist, but a physicist, and if he had ever known the rate at which a poplar grows, he had forgotten it. It could hardly be less than ten or fifteen years…. But if it was fifteen, what then? And if he could have lain entombed for fifteen years, why not for fifty? why not for five hundred? And the turf? How long would it be before the ruins of a house were covered with thick turf? That could hardly happen in fifteen years, even if the ruins were left quite undisturbed… And why had it been left undisturbed in what used to be a busy quarter of London? (The questions thronged now, innumerable and irrepressible.) What had been going on while he had been underground? Were any living men still left? As he asked the last question it was answered. In the distance a couple of figures walked leisurely across the meadows to one of the sheds which Jeremy had vaguely descried, fumbled with the door and went in. They were far too far off for Jeremy to see what manner of men they were; but were they never so gentle, never so kindly, he feared them. He crouched lower down by the entrance to his crevice, and for the second time that morning had half a mind to get back into it, as though it were a magic car that could transport him whence he had come.

The sun rose higher and began to grow hot, and the dew dried swiftly off the grass and the leaves. Very strangely sleep descended on Jeremy, not violently as before, but soft and unnoticed, as though some superior power, seeing his mind reach the limits of conjecture, had gently thrown it out of action. Before he even knew that he was drowsy he had collapsed on the soft turf, his head on the little mound which hid his table top, and there he slept for two or three hours, careless and defenseless in a novel and possibly hostile world. When he woke he found that in sleep his main perplexity had been resolved. He now believed without difficulty that he had been carried in a trance out of his own time, how far he did not know, and the admission of the fact gave him a curious tranquillity and courage to face whatever the consequences might be. It did not, however, alter the ineluctable truth that he was very hungry, and this truth made it plain to him that he must take up the business of living, and run even the risk of meeting the strange people from whom he instinctively shrank. He therefore stood up with a gesture of resolution, and determined to discover, if he could, the trace of Whitechapel High Street, and to follow it in the direction of what had once been London. He remembered having spent a toilsome morning in the South Downs following the track of an old Roman road, and he judged that this ought not to be much more difficult. He had a strange repugnance to throwing himself on the charity of the inhabitants of the new Whitechapel, and an equally strange desire to reach the ruins of Holborn, which had once been his home.

When he had made this resolution he went again into the ghost of Lime Court, took three steps down it, and turned to the left into what he hoped would be the side street leading to the main road. His shot was a lucky one. Banks of grass here and there, mounds crested with bramble, and at one point a heap of moldering brickwork, pointed out his road, and there was actually a little ribbon of a foot-path running down the middle of it. Jeremy moved on slowly, feeling unpleasantly alone in the wide silent morning, and watching carefully for a sign of the great street along which the trams used to run.

The end of the path which he was following was marked by a grove of young trees, surrounded by bushes; and beyond this, Jeremy conjectured, he would most likely find the traces of what he sought. He approached this point cautiously, and when the path dipped down into the grove he slipped along it as noiselessly as he could. When it emerged again he started back with a suppressed cry. Whitechapel High Street was not hard to find, for it was still in being. Here, cutting the path at right angles, was a road — one of the worst he had ever seen, but a road nevertheless. He walked out into the middle of it, stared right and left, and was satisfied. Its curve was such that with the smallest effort he could restore it in his mind to what it had been. On the side from which he came the banks and irregularities, which were all that was left of the houses, stretched brokenly out of sight. On the other side the rubble seemed for the most part to have been cleared, and some of it had been used to make a low continuous fence, which was now grass-grown, though ends of brick and stone pushed out of the green here and there. Beyond it cows were grazing, and the ground fell gently down to a belt of woods, which shut off the view.

Jeremy turned his attention again to the road itself. To a man who recollected the roads round Ypres and on the Somme, it had no new horrors to offer, but to a man who had put these memories behind him and who had, for all practical purposes, walked only yesterday through the streets of London, it was a surprising sight. Water lay on it in pools, though the soil at its side was comparatively dry. The ruts were six or seven inches deep and made a network over the whole surface, which, between them, was covered with grass and weeds. Immediately in front of Jeremy there was a small pit deeper than the ruts, and filled at the bottom with loose stones. It was below the worst of farm tracks, but it was too wide for that, and besides, Jeremy could not rid his vision of the great ghostly trams that flitted through it.

But, bad as it was, it meant life, and even apparently a degree of civilization. And Jeremy felt again an unconquerable aversion from presenting himself to the strange people who had inherited the earth of his other life. A road, to a man who comes suddenly on it out of open country, is always mutely and strangely a witness of the presence of other men. This unspeakable track, more than the path down which he had just walked, more even than the figures he had seen in the distance, filled him with a dread of the explanations he would have to make to the first chance comer he met. His appearance would no doubt be suspicious to them, and his story would be more suspicious still. Either they would not have the intelligence to understand it or, understanding, would not credit it. Jeremy tried to imagine his own feelings supposing that he had met, say, somewhere on the slopes of Leith Hill, a person in archaic costume who affirmed that he had been buried for a century or so and desired assistance. Jeremy could think of no method by which his tale could be made to sound more probable. He therefore, making excuses to himself, shrank back into the grove, and took shelter behind a bush, in the hope, as he put it, of thinking of some likely mendacity to serve instead of the truth. When he was settled there he broke off a young trailer of the hedge rose, peeled it, and ate it. It was neither satisfying nor nourishing, but it had been one of the inexpensive delights of his childhood, and it was something.

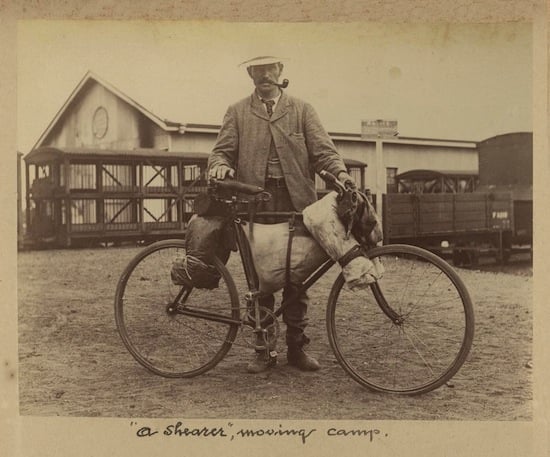

He was just consuming this dainty when a curious rattling and clanking round the curve of the road struck his ear. It rapidly approached, and he started forward to get a view through the leaves of his bush. To his astonishment he saw a young man propelling a bicycle of uncouth appearance, which leapt uncontrollably on the broken road, and threatened to throw its rider at every yard of progress. He peered at it as closely as he could, and had just decided that its odd look came from an unwieldy frame and most unusual tires when, after a last alarming stagger, its front wheel shot into a rut and its rider was deposited within a yard or two of Jeremy’s feet.

Jeremy had then an opportunity of inspecting both at his leisure, and hardly knew which ought to engage his attention first. The machine was sufficiently remarkable, and reminded him of nothing so much as of some which he had seen in the occupied territories of Germany at the end of the war. Its frame was exceedingly heavy, as were all the working parts which could be seen; and it was covered, not with enamel, but with a sort of coarse paint. The spokes of the wheels were half the size of a man’s little finger, and the rims were of thick wood, with springs in the place of tires. The rider, when he had wearily picked himself up and dusted his garments just under Jeremy’s staring eyes, was by no means so unexpected. The dress, from which he was still brushing the dust with, reluctant fingers, consisted of a short brown coat like a blazer, brown breeches, and leather leggings, and on his head he wore a wide-brimmed brown soft hat. His shirt was open at the throat, but below the opening hung a loose and voluminous tie of green linen. His face, on which sat a plainly unwonted expression of annoyance, was mild, candid, and friendly. His voice, when he spoke, was soft and pleasant, and his accent had a strange rich burr in it, which vaguely reminded Jeremy of something he had heard before and could not quite name… something, it seemed, almost grotesque in this connection….

“I never,” said the young man, solemnly but without rancor, to the inattentive universe, “I never will mount one of those devices again.”

Jeremy had ample time to be certain of these details while the young man stood as it were for inspection. When he had dusted himself thoroughly and had looked three or four times round him and up into the sky, apparently to make sure that no celestial chariot was coming to rescue him, he dragged the bicycle from the middle of the road and began to examine it. First of all he tried to wheel it a pace or two, and when it refused to advance he discovered with a gesture of surprise that the chain was off. He slowly lowered the whole machine on to the grass by the roadside and squatted down to adjust the chain. After several fruitless attempts a renewed expression of annoyance crossed his tranquil features, and he sat back on his heels with a sigh.

Jeremy could bear it no longer. Dearer to him even than his European reputation for research into the Viscosity of Liquids was the reputation he had among his friends as a useful man for small mechanical jobs. He would soon have to introduce himself to one or another of what he vaguely supposed to be his descendants. This young man had an unusually calm and friendly appearance, and it was not unlikely that Jeremy might be able to help him in his trouble. He therefore came out of his hiding place, saying brusquely, “Let me see if I can do anything.”

The young man did not start up in fear or even speak. He merely looked slightly surprised and yielded the bicycle without protest into Jeremy’s hands. Jeremy turned it over and peered into it with the silent absorbed competence of a mechanic. Presently he looked up and made a brief demand for a spanner. The young man, still mutely, replied with a restrained but negative movement of his hands. Jeremy, frowning, ran through his own pockets, and produced a metal fountain pen holder, with which in a moment he levered the incredibly clumsy chain back into place. Then he raised the machine and wheeled it a few yards, showing the chain in perfect action. But the front wheel perceptibly limped. Jeremy dropped on one knee and looked at it with an acute eye.

“No good,” he pronounced at last, “it’s buckled. You won’t be able to ride it, but at least you can wheel it.” And he solemnly handed the machine back to its owner.

“Thank you very much,” said the young man gently. Jeremy could still hear that odd, pleasant burr in his voice. And then he enquired with a little hesitation, “Are you a blacksmith?”

“Good Heavens, no!” Jeremy cried. “Why —”

The young man appeared to choose his words carefully. “I’m sorry. You see, you know all about the bicycle, and… and… I couldn’t quite see what your clothes were….” He slurred over the last remark, perhaps feeling it to be ill-mannered, and went on hastily: “I asked because in the village I’ve come from, just a couple of miles down the road, the blacksmith is dead and…” He paused and looked at Jeremy expectantly.

Jeremy on his side realized that the moment had come when he must either tell his amazing story or deliberately shirk it. But while he had been bending over the bicycle a likely substitute had occurred to him, a substitute which, however, he would have hesitated to offer to anyone less intelligent and kindly in appearance than his new acquaintance. He hesitated a moment, and decided on shirking, or, as he excused it to himself, on feeling his way slowly.

“I don’t know,” he said with an accent of dull despair. “I don’t know who or what I am. I think I must have lost my memory.”

The young man gave a sympathetic exclamation. “Lost your memory?” he cried. “Then,” he went on, his face brightening, “perhaps you are a blacksmith. I can tell you they want one very badly over there…” But he caught himself up, and added, “Perhaps not. I suppose you can’t tell what you might have been.” He ceased, and regarded Jeremy with benevolent interest.

“I can’t,” Jeremy said earnestly. “I don’t know where I came from, or what I am, or where I am. I don’t even know what year this is. I can remember nothing.”

“That’s bad,” the young man commented with maddening deliberation. “I can tell you where you are, at any rate. This is called Whitechapel Meadows — just outside London, you know. Does that suggest anything to you?”

“Nothing… nothing… I woke up just over there”— he swung his arm vaguely in the direction of the ruins of the warehouse —”and that’s all I know.” He suppressed an urgent desire to emphasize again his ignorance of what year it was. Something told him that a man who had just lost his memory would be concerned with more immediate problems.

“Well,” said the young man pleasantly at last, “do you think you came from London? If you do, you’d better let me take you there and see you safe in one of the monastery hospitals or something of that sort. Then perhaps your family would find you.”

“I think so.” Jeremy was uncertain whether this would be a step in the right direction. “I seem to remember… I don’t know….” He paused, feeling that he could not have imagined a situation so difficult. He had read a number of books in which men had been projected from their own times into the future, but, by one lucky chance or another, none of them had any trouble in establishing himself as the immediate center of interest. Yet he supposed it would be more natural for such an adventurer to be treated as he was going to be treated — that is to say as a mental case. It would be tragically absurd if he in his unique position were to be immured in a madhouse, regarded as a man possessed by incurable delusions, when he might be deriving some consolation for his extraordinary fate in seeing how the world had changed, in seeing, among other things, what was the current theory of the Viscosity of Liquids, and whether his own name was remembered among the early investigators into that fascinating question.

While he still hesitated his companion went on in a soothing tone, “That will be much the best way. Come with me if you think you’re well enough to walk.”

“Oh, yes… yes…” distractedly. And as a matter of fact, his hunger and his increasing bewilderment aside, Jeremy had never felt so well or so strong in his life before. He was even a little afraid that the activity of his manner might belie the supposed derangement of his mind. He therefore attempted to assume a somewhat depressed demeanor as he followed his new friend along the road.

The young man was evidently either by nature not loquacious, or else convinced that it would be unwise to excite Jeremy by much conversation — perhaps both. As they went along he gave most of his attention to the conduct of his bicycle, and only threw over his shoulder now and again a kindly “Do you remember that?” or “Does that remind you of anything?” as they passed what would apparently be landmarks familiar to any Londoner in the habit of using that road.

But all were equally strange to Jeremy, and he gazed round him keenly to guess if he could what sort of people they were among whom he had fallen. Clearly, if he were to judge by the man who was walking at his side, they were not barbarians; and yet everywhere the countryside showed evidence of decay, which totally defeated all the expectations of the prophets of his own time. As they drew closer to London, which was still hidden from them by belts of trees, the broken meadows of Whitechapel gave place to cleared plots of garden, and here and there among them stood rude hovels, huts that no decent district council would have allowed to be erected. Jeremy, gazing at them as closely as he could without exciting the attention of his guide, thought that many of them seemed to have been built by piling roughly together fragments of other buildings. Presently a gang of laborers going out to the fields passed them, saluting Jeremy with a curious stare, and his companion, when they were able to transfer their gaze to him, with touched caps, whether because they knew him or merely out of respect for his appearance Jeremy could not decide. But it was surprising how familiar their look was. They were what Jeremy had encountered many hundreds of times in country lanes and the bars of country inns; and it was only vaguely and as it were with the back of his consciousness that he perceived their ruder dress and the greater respectfulness of their manner.

The transition from the fields to the town was abrupt. They reached and passed a little wood which bordered both sides of the road, and immediately beyond it the first street began. The houses were almost all of Jeremy’s own day or before it, but though they were inhabited they were heavy with age, sagging and hanging in different directions in a manner which betokened long neglect. At the end of the street a knot of loiterers stood. Behind them the street was busy with foot passengers, and Jeremy stared along it to a tangle of houses, some old and some new, but nearly all wearing the same strange air of instability and imminent collapse. Their appearance affected him, as one is affected when one wakes in an unfamiliar room, sleepily expecting to see accustomed things and grows dizzy in substituting the real picture for the imagined. He caught his breath and paused.

“What’s the matter?” asked the young man, instantly solicitous.

“Nothing,” Jeremy replied, “only feel faint… must rest a minute.” He leant against a mass of ruined and lichened brickwork, breathing shortly and jerkily.

“Here,” cried his companion, dropping the bicycle, “sit down till you feel better.” And, exerting an unsuspected strength, he took Jeremy bodily in his arms and lowered him gently till he reclined on the grass. Jeremy looked up, grateful for his kindness, which was reassuring, though he knew that it did not spring from sympathy with his real perplexities. But he immediately dropped his eyes and clenched his hands while he strove to master his doubts. Would it not perhaps be the wiser plan to confess his position to this young man and take the risk of being thought a madman? And a moment’s reflection convinced him that he would never have a better opportunity. The face that now leant anxiously above him was not perhaps so alert or active in appearance as he could have wished; but it was extraordinarily friendly and trustworthy. If the young man could be made to believe in Jeremy’s story, he would do all that was possible to help him. Jeremy made his decision with a leap, and looking up again said thickly:

“I say…. I didn’t tell you the truth just now.”

“What? Don’t talk. You’ll feel better in a moment.”

“No, I must,” Jeremy insisted. “I’m all right; I haven’t lost my memory. I wish to God I had lost it.”

The young man showed for the first time serious symptoms of surprise and alarm. “What,” he began, “are you a —”

Jeremy silenced him with an imperative wave of the hand. “Let me go on,” he said feverishly, “you mustn’t interrupt me. It’s difficult enough to say, anyway. Listen.”

Then, brokenly, he told his story in a passion of eagerness to be as brief as he could, and at the same time to make it credible by the mere force of his will. When he began to speak he was looking at the ground, but as he reached the crucial points he glanced up to see the listener’s expression, and he ended with his gaze fixed directly, appealingly, on the young man’s eyes. But the first words in response made him break into a fit of hysterical laughter.

“Good heavens!” the young man cried in accents of obvious relief. “Do you know what I was thinking? Why, I more than half thought you were going to say that you were a criminal or a runaway!”

Jeremy pulled himself together with a jerk, and asked breathlessly, “What year is this? For God’s sake tell me what year it is!”

“The year of Our Lord two thousand and seventy-four,” the young man answered, and then suddenly realizing the significance of what he had said, he put his hand on Jeremy’s shoulder, and added: “All right, man, all right. Be calm.”

“I’m all right,” Jeremy muttered, putting his hands on the ground to steady himself, “only it’s rather a shock — to hear it —” For, strangely, though he had admitted in his thoughts the possibility of even greater periods than this, the concrete naming of the figures struck him harder than anything that day since the moment in which he had expected to see houses and had seen only empty meadows. Now when he closed his eyes his mind at once sank in a whirlpool of vague but powerful emotions. In this darkness he perceived that he had been washed up by fate on a foreign shore, more than a century and a half out of his own generation, in a world of which he was ignorant, and which had no place for him, that his friends were all long dead and forgotten…. When his mind emerged from this eclipse, he found that his cheeks were wet with tears and that he was laughing feebly. All the strength and activity were gone out of him; and he gazed up at his companion helplessly, feeling as dependent on him as a young child on its parent.

“What shall we do now?” he asked in a toneless voice.

But the young man was turning his bicycle around again. “If you feel well enough,” he answered gently, “I want you to come back and show me the place where you were hidden. You know… I don’t doubt you. I honestly don’t; but it’s a strange story, and perhaps it would be better for you if I were to look at the place before any one disturbs it. So, if you’re well enough…?” Jeremy nodded consent, grateful for the kindness of his friend’s voice, and went with him.

The way back to the little grove where they had first met seemed much longer to Jeremy as he retraced it with feet that had begun to drag and back that had begun to ache. When they reached it, the young man hid his bicycle among the bushes, and asked Jeremy to lead him. At the edge of the crevice he paused, and looked down thoughtfully, rubbing his chin with one finger.

“It is just as you described it,” he murmured. “I can see the tabletop. Did you look inside when you had got out?” It had not occurred to Jeremy, and he admitted it. “Never mind,” the young man went on, “we’ll do that in a moment.” Then he made Jeremy explain to him how the warehouse had stood, where Lime Court had been, and how it fell into the side-street. He paced the ground which was indicated to him with serious absorbed face, and said at last: “You understand that I haven’t doubted what you told me. I felt that you were speaking the truth. But you might have been deluded, and it was as much for your own sake…”

Jeremy interrupted him eagerly. “Couldn’t you get the old records, or an old map of London that would show where all these things were? That would help to prove the truth of what I say.”

The young man shook his head doubtfully. “I don’t suppose I could,” he answered vaguely, his eyes straying off in another direction. “I never heard of such things. Now for this…” And turning to the crevice again he seized the tabletop and with a vigorous effort wrenched it up. As he did so a rat ran squeaking from underneath, and scampered away across the grass. Jeremy started back bewildered.

“You had a pleasant bedfellow,” said the young man in his grave manner. Jeremy was silent, struggling with something in his memory that had been overlaid by more recent concerns. Was it possible that he was not alone in this unfamiliar generation? With a sudden movement he jumped down into the open grave and began to search in the loose dust at the bottom. The next moment he was out again, presenting for the inspection of his bewildered companion an oddly-shaped glass vessel.

“This is it!” he cried, his face white, his eyes blazing, “I told you I came to see an experiment —” Then he was checked by the perfect blankness of the expression that met him. “Of course,” he said more slowly, “if you’re not a scientist, perhaps you wouldn’t know what this is.” And he began to explain, in the simplest words he could find, the astonishing theory that had just leapt up fully born in his brain. He guessed, staggered by his own supposition, that Trehanoc’s ray had been more potent than even the discoverer had suspected, and that welling softly and invisibly from the once excited vacuum-tube which he held in his hand, it had preserved him and the rat together in a state of suspended animation for more than a century and a half. Then with the rolling of the timbers over his head and the collapse of the soft earth which had gathered on them, the air had entered the hermetically sealed chamber and brought awakening with it.

As his own excitement began to subside he was checked again by the absolute lack of comprehension patent in his companion’s face. He stopped in the middle of a sentence, feeling himself all astray. Was this ray one of the commonplaces of the new age? Was it his surprise, rather than the cause of it, which was so puzzling to his friend? The whole world was swimming around him, and ideas began to lose their connection. But, as through a mist, he could still see the young man’s face, and hear him saying seriously as ever:

“I do not understand how that bottle could have kept you asleep for so long, nor do I know what you mean by a ray. You are very ill, or you would not try to explain things which cannot be explained. You do not know any more than I what special grace has preserved you. Many strange things happened in the old times which we cannot understand to-day.” As he spoke he crossed himself and bowed his head. Jeremy was silenced by his expression of devout and final certainty, and stifled the exclamation that rose to his lips.

* “he lay there with the circumstances in which he had been buried”: This strange turn of phrase, which appears in Chapter 3 of every e-book version of The People of the Ruins, was created by a careless transcriber who typed or scanned in the beginning of the last sentence on page 35 of the book’s first edition, which ends on page 36 (“What more certain than that in that catastrophe, which he now so clearly recalled, his back had been broken, so that he lay there with no more than an hour or two to live?”), and the end of the first sentence on page 38, which began on page 37 (“Considering the circumstances in which he had been buried, he would certainly have expected to hear something going on.”) In other words, every digital (and print-on-demand) version of The People of the Ruins is missing pages 36 and 37. Our edition of the text corrects this error.

NEXT WEEK: “Jeremy pondered over again the vision raised by these words. He could see the earth ravaged by exhausted enemies, too evenly matched to bring the struggle to an end until exhaustion had reached its lowest pitch. He could see all the mechanical wonders of his own age smashed by men who were too weak to prevail, but who were strong enough not to endure the soulless contrivances which had brought them into servitude.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.