The People of the Ruins (8)

By:

July 12, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eighth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “Who and what was he? He told himself — a sport of nature, a young man unnaturally old, an old man unnaturally young. Could he be certain yet what trick it was that Trehanoc’s ray had played on him? Might he not, one day, to-morrow or a year hence, perhaps in her very arms, suddenly expire, even crumble into dust? He shuddered in the chilling air of these suggestions and was filled with misery. But the next moment he could see himself confessing his misery to the Lady Eva and receiving her comfort.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

CHAPTER VIII

DECLARATION OF WAR

The dark and undefined cloud which had fallen upon the reception seemed to have overshadowed the Treasury as well. The Speaker had precipitately driven thither, taking Henry Watkins with him in the carriage and not waiting for Jeremy, who reached the door only in time to see that he must follow on foot. The Speaker’s unexpected return, coupled with the unusual expression on his face and perhaps some rumor already set afloat, had unsettled the household. When Jeremy arrived he found the clerks and even the servants, together with the attendants of the Lady Burney and the Lady Eva, standing about in little groups in the entrance hall. They were talking among themselves in low voices, and they all raised their eyes questioningly to his as he passed by. There was a universal atmosphere of confusion and alarm.

At the door which led from the entrance-hall towards the Speaker’s room, Jeremy paused disconsolately, uncertain what he ought to do. The Speaker had asked for his help, but had not stayed for him. Perhaps he ought to go to the Speaker; but he was unwilling to intrude into what seemed to be a council of the first importance. His doubts were relieved by a servant, who came anxiously searching among the loiterers and appeared relieved when he caught sight of Jeremy.

“Here you are, sir!” he said. “The Speaker has been asking for you ever since he came back. Will you please go to his room at once?” Jeremy’s sense of a moment of crisis was by no means lessened as he threaded the dark, empty corridors of the private wing.

When he entered he found himself unnoticed, and had a few seconds in which to distinguish the members of the little group clustered at the other end of the room. The Speaker was standing motionless, with his eyes turned upwards to the ceiling, in an attitude apparently indicating complete unconcern. Yet, to Jeremy he seemed to be controlling himself by an enormous effort of will, while his whole body quivered with suppressed excitement. Below him and, to the eye, dominated by him, five men sat around a table. Jeremy saw at once the Canadian and Henry Watkins and another chief notable, named John Hammond, with whom he was slightly acquainted. The others had their backs to him; but their backs were unfamiliar, somehow out of place, with something uneasy and hostile in the set of their shoulders. As he came into the room, Henry Watkins was leaning forward to one of these strangers and saying earnestly:

“I want to make certain that we understand what this sentence means.” He tapped a paper in front of him as he spoke.

“T’ letter meaans what it saays,” the stranger replied gruffly. His words and the broad, rasping accent in which they were spoken came to Jeremy as a shock, as something incomprehensibly foreign to what he had expected. His colleague nodded vigorously, and signified his agreement in a sound between a mutter and a growl.

“Yes,” Henry Watkins began again patiently; “but what I want to know —”

The Speaker suddenly forsook his rigid posture, with the effect of a storm let loose, and, striding to the table, struck it violently with his fist. It seemed, as if the last fetter of his restraint had given way without warning.

“That’s no matter,” he cried hoarsely. “What I want to know is this: if I make another offer, will you take it back to your master?”

The stranger squared his shoulders and thrust his chin forward with an air of dogged ferocity. “We caame to get yes or noa,” he answered in a deep grumbling voice. “T’ letter saays soa.”

Henry Watkins started at this outburst in the negotiations and looked around him with an appearance of fright. In doing this he caught sight of Jeremy hesitating by the door, and whispered a word to the Speaker, who cried out, without moderating the violence of his tone: “There you are! Come here now, I want you.” And turning again to the strangers, he added, with an odd note of triumph: “This is Jeremy Tuft. Maybe you’ve heard of him.”

The strangers, who had not yet noticed Jeremy’s arrival, slewed around together and stared at him; and one of them said: “Oh, ay, we’ve heerd on him, reet enough.” The others at the table stared too, while Jeremy reluctantly advanced. But before he could speak, Henry Watkins sprang up and murmured importunately in the Speaker’s ear. Jeremy could catch the words:

“Talk privately… before we decide…”

“Very well,” said the Speaker roughly, aloud. “Have it your own way. But I won’t change my mind.”

Henry Watkins returned to the table and addressed the strangers suavely: “The Speaker will give you his answer in a very short time,” he said. “Will you be so good as to withdraw while he considers it?” And, when they had uncouthly assented, he conducted them to the door, showed them into an ante-room, and returned, his face full of anxiety.

Jeremy stood apart in a condition of great discomfort. He realized that he was regarded by all, save the Speaker, as an intruder, the reason for whose presence none could conjecture. He was not relieved by the dubious glance which Henry Watkins threw at him before he began to speak. But the Speaker made no sign, and the anxious counselor proceeded, with an air of distraction and flurry.

“Think, sir,” he pleaded, “before you refuse. It is so grave a thing to begin again — after a hundred years. And who can tell what the end of it may be? We know that they are formidable —”

“All this is nonsense to Jeremy Tuft,” the Speaker interrupted harshly. “We must tell him what the matter is before we go any further.” Henry Watkins, with a movement of his hands, plainly expressed his opinion that there was no good reason why it should not all remain nonsense to Jeremy; and Jeremy felt slightly less at ease than before.

But the Speaker had begun to explain, with the sharp jerkiness of impatience in his voice: “We’ve had a message from the people up north. Perhaps you could see for yourself what sort of men they are. They are very unlike any one you have ever met here — rough, fierce, quarrelsome men. They have kept some of their machinery still going up there — in some of the towns they even work in factories. They have been growing more and more unlike us for a hundred years, and now the end has come — they want to force a quarrel on us. Do you understand?”

Jeremy replied that he did, and thought that he was beginning to understand a great deal besides.

“Well, then,” the Speaker went on, growing a little calmer, “I told you when first we met that we were standing on the edge of a precipice. Now these are the people that want to throw us over. The chief of them, the Chairman of Bradford, has sent me a message. I won’t explain the details to you. It comes to this, that in future he proposes to collect the taxes in his district, not for me, but for himself. I must say he very kindly offers to send me a contribution for the upkeep of the railways. But he wants a plain yes or no at once; and if we say no, then it means WAR!” In the last sentence his voice had begun to run upwards: he pronounced the final word in a sudden startling shout, and then stood silent for a moment, his eyes burning fiercely. When he continued, it was in a quieter and more reasonable tone. “There has been no fighting in this country since the end of the Troubles, a hundred years or so ago. A brawl here and there, a fight with criminals or discontented laborers —I don’t say; but no more than enough to make our people dislike it. Of all of us here in this room, only you and Thomas Wells know what war is. Now”— and here he became persuasive and put a curious smooth emphasis on each word —”now, knowing all that you do know, what advice would you give me?”

Jeremy stood irresolute. Henry Watkins and John Hammond seemed to throw up their hands in perplexed despair, and the Canadian’s thin, supercilious smile grew a trifle wider and thinner. The Speaker waited, rocking hugely to and fro on his feet with a gentle motion.

“I think,” Jeremy began, and was disconcerted to find himself so hoarse that the words came muffled and inaudible. He cleared his throat. “I think I hardly know enough about it for my advice to be of any use. I don’t even know what troops you have.”

The Speaker made a deep booming sound in his chest, clasped his hands sharply together, and looked as though he were about to burst out again in anger. Then he abruptly regained his self-command and said: “Then you shall speak later. Henry Watkins, what do you say? Remember, we must make up our minds forever while we are talking now. It will not do to argue with them, or temporize or make them any other offer.”

Henry Watkins got up from his seat and went to the Speaker’s side as though he wished to address him confidentially. Jeremy had an impression of a long dark face, unnaturally lengthened by deep gloom, and two prominent eyes that not even the strongest emotion could make more than dully earnest.

“I beg of you, sir,” he implored, low and hurried, holding out his hands, “to attempt to argue with them, to offer them some compromise. You know very well that they are forcing this quarrel on us, because they are sure that they are the stronger, as I believe them to be. And anything, anything would be better than to begin the Troubles again!”

The Speaker surveyed him as if from an immense height. “And do you think that we can avoid the Troubles again, and worse things even than that, in any way except by defeating these people? Am I to surrender all that my grandfather and my great-grandfather won? Do you not see that they have sent us just these two men, stupider and stubborner even than the rest, so that we shall not be able to argue with them? They have been told to carry back either our yes or our no. If we do not give them a yes, they will take no by default. There is no other choice for us. What do you think, John Hammond?”

“I agree with Henry Watkins,” said the big man hastily. He had not spoken before, and seemed to do so now only with great reluctance.

“Then we need not hear your reasons. And you, Thomas Wells?”

“Why, fight,” said the Canadian promptly; and then he continued in a deliberate drawl, stretching himself a little as he spoke: “These folks are spoiling for trouble, and they’ll give you no peace until they get it. I guess your troops aren’t any good —I’ve seen some of them — but I know no way to make them so except by fighting. And besides, I’ve an idea that there’s something else you haven’t told us yet.”

Jeremy shot a suspicious glance at him, and received in return a grin that was full at once of amusement and dislike. The Speaker appeared to be balancing considerations in his mind. When he spoke again, it was in a tone more serious and deliberate than he had yet used.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “my decision remains unaltered. I shall refuse and there will be war. But Thomas Wells is right. I have had something in my thoughts that I have not yet disclosed to you. But I will tell you now what it is, because I do not wish you to lose your spirits or to be half-hearted in supporting me. Only I must command you”— he paused on the word, looked around sternly, and repeated it —”I must command you not to speak a word of it outside this room until I give you leave.” He paused again and surveyed them with the air of a man who delays his certain triumph for a moment in order the better to savor it. “Gentlemen, when our troops take the field against these rebels, they will have something that no other army in the world has got. They will have guns!”

The great announcement had come, had passed, and seemed to have failed of its effect. Silence reigned in the council. Henry Watkins shifted from one foot to the other and regarded the Speaker with gloomy intentness. Then Thomas Wells broke the hush, with a faint tone of disappointment in his voice:

“Is that it? Well, I don’t know how that will work out. I thought that perhaps you had got some of the bosses up there in your pay.”

Henry Watkins was as silent as his companion, bewildered, disturbed, apprehensive. But the Speaker continued, his air of jubilation increasing rather than diminishing.

“And not only have we guns, but we have also a trained artilleryman to handle them. Jeremy Tuft, I must tell you, fought in the artillery in the great war against the Germans before the Troubles began. And now, Jeremy Tuft, let us hear your opinion, remembering that we have guns and they have none. Do you think we should fight or surrender?”

Jeremy was hard put to it not to give way physically before the old man’s blazing and menacing stare. His mind scurried hastily through half a hundred points of doubt. How could he know, when he had been in this world no more than a few weeks? And yet it seemed pretty clear, from what he had heard, that the-soldiers from Yorkshire would be better than those that the Speaker had at his disposal. He could see only too plainly that the Speaker was trusting to the guns to work a miracle for him. He remembered that the guns were only just finished, had not been tested, that no gun-crew to fight them had yet been trained or even thought of. He had a sick feeling that an intolerable responsibility rested on him, that he must explain how much the effect of two guns in an infantry battle would depend on luck. He remembered that time at Arras, when they had got properly caught in the enemy’s counter-battery work, and he had sat in his dug-out, meditating on the people, whoever they were, that had started the war, and wondering how human beings could be so diabolical… He woke abruptly from this train of thought as he raised his eyes and saw the Speaker still regarding him with that terrible, that numbing stare. His strength gave way. He stammered weakly:

“Of course, the guns would make a great difference….”

The Speaker caught up his words. “They would make just the difference we need. That is why I have made up my mind to fight now. Let those two men come in again.”

There was dead silence in the room for a moment, and Jeremy was aware of the progress of a breathless spiritual conflict. He could feel his own inarticulate doubts, the timidity of Watkins and Hammond, the cynical indifference of the Canadian, hanging, like dogs around the neck of a bull, on the old man’s fanatical determination. Then something impalpable seemed to snap: it was as though the bull had shaken himself free. Without uttering a sound, Henry Watkins went to the door of the ante-room and held it open. The two envoys from the north again appeared. They seemed unwilling to come more than a pace into the room; perhaps they thought it unnecessary since they wished to hear only a single word.

The Speaker was as anxious as they to be brief. “I refuse,” he said with great mildness.

“That’s t’ aanswer, then?” asked the first envoy with a kind of surly satisfaction.

“That’s t’ aanswer. Coom on,” his companion said, before any one else could reply.

“Good daay to you then, sirs,” the first muttered phlegmatically; and with stumping strides they lumbered to the door. Henry Watkins hurried after them to find a servant to bring them their horses.

No less than the rest the Lady Eva was disturbed and made uneasy in her mind by the unexpected end of Henry Watkins’s reception. The short drive back to the Treasury, sitting beside her mother in the vast, lumbering carriage, was a torment to her. Involuntarily she asked questions, well aware that the Lady Burney neither knew, nor was interested in, the answers. She was obliged to speak to assuage her restlessness, and expected the reproof which she received.

“It’s not your business,” said the Lady Burney heavily. “You must not meddle in your father’s affairs. It shows a very forward and unbecoming spirit in you to have noticed that anything happened out of the ordinary. What people would say of you if they knew as much of your behavior as I do, I simply cannot think. They must see too much as it is. Remember that we ought to set an example to other people.”

The Lady Eva was silent, white with restraint and anxiety. But when they arrived at the Treasury and came into the atmosphere of expectancy which filled the entrance-hall, she again showed signs of excitement, and seemed to wish to stop and share in the general state of suspense. Her mother ordered her to her room in a thick intense whisper. She remembered herself and went on, sighing once sharply.

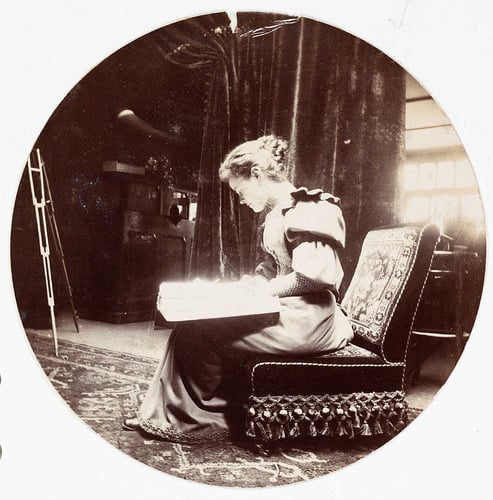

She found her room empty. It was a pleasant place, looking over the gardens, furnished in an awkward and mixed style which reflected her distaste for her mother’s notions of decoration, combined with her own inability to think of any better substitute. A riding-whip and gloves were thrown down on a table, beside a half-finished piece of needlework. Writing materials and a book lay on another. One of her eccentricities, not regarded so severely by the Lady Burney as the nest, was her wish to retain such slight knowledge of the arts of reading and writing as the scanty education of the women of that time had given her. But it was a hard business, starting from so insecure a foundation and proceeding with so little encouragement. The old books that she was able to obtain were very dull, very hard to understand, and told her little of what she wanted to know. Her companions of her own age laughed at her heartily for reading with so much devotion, after she had been released from the school-room, the works of the great poet, Lord Tennyson, from which they had all been taught their own language. She desired vaguely to be able to help her father, whose loneliness she obscurely but poignantly felt. But when in order to understand the old times she struggled through ragged and mildewed books, she despaired at the little assistance she was able to get from them.

She once expressed a timid wish that she might be allowed to learn history from Father Henry Dean, of whose knowledge she had heard confused but marvelous stories. But on this occasion her father had unexpectedly joined her mother to prevent her. He had said bluntly that the priest was an addled old man, while the Lady Burney had said that the suggestion was both improper and dangerous. Between the two opinions, her wish was effectually frustrated. Indeed, she got little encouragement from her father, whose loneliness often seemed to her to be in great part purely wilful. Now and then he would listen to her for a few minutes, and then rhapsodize cloudily for a long time on his hopes and fears. But when he did this, after the first few sentences he was up and away from her; and she soon realized that he talked to her only instead of talking to himself, and did not for the purpose much alter his method of address.

A minute or two after she came into her room, two of her attendants followed her, asking, without much hope, for news. She shook her head sharply, with compressed lips. She had no news, she knew nothing of the danger that threatened her father and had shaken his steady old hand so abruptly while he was reading that mysterious letter. The two girls broke at once into a babble of rumors and conjectures. The plague had reached England again, or the Chinese had begun to invade Europe, or the Pope had done something or other that was unexpected, it was not clear what.

These attendants were daughters of good families who came to be half maids, half companions to the Lady Burney and the Lady Eva for a year or two, as a way of graduating in the world, much as young men came to be clerks to the Speaker. But the cases were not quite parallel. All young men of family entered the Speaker’s service, or would do so if they could. There was a certain tradition of gentility in the work of government. But only the daughters of the poorer and smaller houses came to wait on the Speaker’s wife and daughter. The rich families, though they obeyed the Speaker, would not accord him royal prestige or his wife and daughter the privilege of noble ladies-in-waiting. They treated him and his household with respect, not with deference. Only the lesser among them thought that something might be gained by their daughters holding positions at what they would fain regard as a court, or that they might perhaps make good marriages, a hope which now and then miscarried into something less gratifying. They maintained that it was an honor to serve the ruling family, and were sneered at by their greater fellows.

The Lady Eva, though she was often indolent and was pleased to be waited on, would have preferred to be attended by servants. These girls claimed some sort of equality with her, and, though she had no objection to that, she wished that she could prevent them speaking to her, unless she called on them: She found them tedious. Now she listened to them patiently, and said at last with a faint ironic smile:

“Do you really know anything about it?” They began to protest and to double their rumors, but she stopped them with a lifted hand. “There is a council in my father’s room, is there not?” And when they had said that there was, she went on: “Can you tell me who has been called to it?”

“Jeremy Tuft was called to it just before we came to you,” answered Rose, simpering a little and placing her head on one side. Jeremy did not know that among the young girls in the Treasury he was the object of some longings and the subject of some confessions. He drew attention because of the air of mystery which surrounded his short and rather commonplace person. It was fashionable to affect a deliciously shuddering attraction towards the elements of eeriness and terror in what was known of his story. But this fashion was not allowed to interfere with any more practical project of love-making that happened to be going.

“I saw him go,” affirmed Mary with an even more pronounced simper.

“Is Thomas Wells there?” the Lady Eva shot at her quickly. Mary winced, looked guilty and said that she believed he was. Then she fell silent in a self-conscious attitude.

The Lady Eva frowned a little. These girls, though she despised them for their shallowness, led fuller lives than she. They conformed more easily than she did with the prevailing ideal of womanly conduct; and yet in the Treasury they were free to do much what they pleased, to choose lovers if they were foolish enough… as she guessed this girl had been. And the reflection had annoyed her, for she thought it likely that she would have to marry Thomas Wells. He and her father had been bargaining interminably about something, her father importunate but cozening, Thomas Wells smiling but obdurate. It might occur to her father at any moment to throw her person into the scale; and she would not like for a husband the lover of one of her attendants. Then, as she stood musing, it suddenly occurred to her with great force that she would not like to marry Thomas Wells in any circumstances. Strange! She had been long accustomed to the idea that she, her father’s only child, must marry some one who would be chosen to become his heir; and she had quite calmly contemplated the likelihood of Thomas Wells being chosen. Only to-day did she perceive that the idea was distasteful to her, and she wondered why. A vague answer presented itself….

“Go back, both of you,” she commanded, “and bring me the news when you hear any.” They left her at once, Rose anxious to return to the center of excitement, and Mary glad to escape any further uncomfortable questions.

The Lady Eva, left alone, walked up and down her room with short, impatient steps. It was very difficult to wait thus for news, more difficult still in view of the fact that she might not get any. She conceived cloudy romantic notions of intervening in the council, of persuading her father in the middle of it that she understood him and was with him against all the rest of the world. She walked towards the door in an exalted fit, certain that now at least in this moment of anxiety she could convince him. Then she remembered other appeals, made when she was alone with him and when his mood had seemed to promise sympathy. But he had smiled at her, patted her head or her hand, and answered vaguely in words that meant nothing and humiliated her. Once, gathering from one of the soliloquies, in which he so evidently forgot her presence, that he was concerned by the state of the railways, she had brooded on the problem through sleepless nights, at last hitting on a plan, which she laid eagerly before him. It had seemed as crude and childish to her as to him, after his first comment. A flash of realism showed her the injured and astonished big men at the council, if she appeared there, the grinning contempt of Thomas Wells, her father’s anger. She turned away again from the door.

Minutes passed. She went through stages of careless dullness, of unbearable suspense. At last, moved by an ungovernable longing, she left the room. She intended no longer to go to her father, but she would at least see the door behind which he was sitting with the others. She had an unreasonable certainty, which she could not examine, that waiting would be easier near the place where all was being decided.

She slipped along the corridor as softly as she could, ruefully aware that she did not usually move quietly and had often been reproved for it. But the intensity of her purpose helped her to avoid anything that could draw notice to her strange conduct. Soon the corridor was cut by another at right angles, which a few steps to the left led to the door of the Speaker’s room. At the corner the Lady Eva paused and looked cautiously around. In this part of the ill-constructed house reigned a perpetual dusk, and any passer-by would be heard by her long before he could see her.

Her certainty was justified. Waiting was easier here; and the time slipped by less oppressively. She did not know how long she had been standing pressed close against the wall, when her father’s door opened and two men came out and stamped up the corridor to the right. Even in that gloom she could see that they were strangers; and their odd looks and something odd in their manner, as though they were departing with a sinister purpose, increased her curiosity. She craned her neck to keep them in sight as long as she could, and drew back hastily when Henry Watkins came out. He was obviously distressed, and, as he went by her, following the strangers, he was rapidly clenching and unclenching his hands.

A minute passed. Then the door opened again and Thomas Wells sauntered into the corridor. He hesitated by the corner where she stood, and then thrust his hands into his pockets, and strolled after the others, whistling under his breath. She could still hear his steps when John Hammond emerged and also followed with bowed shoulders and dejected bearing. The Lady Eva’s sense of terror grew greater and she wondered whether the news, whatever it might be, would not be come at easier elsewhere. But her father and Jeremy Tuft were still conversing behind the closed door and she longed to know what they were saying. When she first met him she had had a fleeting idea that he might prove to be a bridge between her and her father.

A long interval elapsed and left her still in suspense. Once she went a few paces in the direction of her own room, but she was ineluctably drawn back again. She stared desperately behind her, to the right, at the ground, anywhere rather than at her father’s door, which had for her a fascination she felt she must resist. She was not looking at it when she heard the sound of the handle. When she looked, it was standing wide, and Jeremy and her father were framed in the opening, their faces lit from the windows in the room.

Her father’s face wore an expression of exultation which she had never seen there before, and, with a hand on his shoulder, was stooping over Jeremy, who looked worried, sullen, fatigued.

“Then all will be ready in a week,” the old man was saying.

“Yes, they’ll be ready… so far as that goes,” Jeremy replied in a heavy toneless voice. “But there’s another thing we haven’t thought of. They haven’t been tested yet.”

“They can’t be tested now,” the Speaker said firmly. “It would take too long, and besides, we mustn’t have the slightest risk of the news leaking out before we first use them. And you say that you are satisfied with them, don’t you?”

“Yes, as far as I can see,” Jeremy muttered. “But there may be something wrong that I haven’t noticed.”

“No doubt there may,” the Speaker agreed. “But if there is, it would be too late to remedy it; and we should certainly be beaten without them. We may as well disregard that.”

“But if there is,” Jeremy said with an air of protest, raising his voice a little, “we may be…”

“Yes, yes,” the Speaker murmured, “you may all be blown up. But there…” He drew Jeremy by the shoulder into the corridor, and both their faces came into the shadow. The Lady Eva, seized by a sudden terror, picked up her skirts and ran, miraculously noiseless, back to her room.

NEXT WEEK: “The Spiritualists owned no law or discipline in the spiritual world, but acted on the latest intelligence received from the dead. Most of them held firmly that evil was a delusion, a doctrine which had come to have a strange influence on conduct. All of them believed without a question in the future life; and the absolute quality of their belief, the Speaker thought, had gradually changed among them the distaste for fighting which at one time possessed the whole country. It would further, he thought, make them formidable soldiers.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.