The People of the Ruins (10)

By:

July 26, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the tenth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “The collapse of other means of crossing the river sent them round by Westminster Bridge, which shook and rumbled ominously under the weight of the guns, and thence along Whitehall in the direction of Charing Cross Road. Jeremy’s route had been indicated to him by the Speaker without the help of a map; but, to his surprise, he had been able to recognize the general line of it by means of the names.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

THE BATTLE

Jeremy’s orders had been to meet the Speaker near the church on the hill; and thither he rode, not staying to look about him. By the long, cold shadow of the church tower stood a little knot of people whom he recognized for the Speaker and his staff. He rode up to them, dismounted stiffly, and saluted, as the old man came forward to meet him.

“You have come, then,” said the Speaker, in his usual thick soft voice, laying an almost affectionate hand on his arm. “And are the guns safe?”

“Quite safe,” Jeremy answered, shivering a little and stamping his feet for warmth.

“I knew I could trust you to bring them,” the Speaker murmured. “Come over here and they shall give you a warm drink.”

Jeremy went with him to the little knot of officers, who were standing just in the growing sunlight, and took from a servant a great mug which he found to be full of inferior, sickly-flavored whisky and hot water, highly sweetened. He lifted his head from it, coughing and gasping a little, but immediately found that he was warmer and stronger.

“All the army is assembled,” the Speaker told him. “We continue the march in half-an-hour. The enemy pushed past St. Albans last night and they are camped between here and there. The battle will be two or three miles north of this.”

Jeremy was now sufficiently revived to look about him with interest. Here, as almost everywhere in the farthest limits of London, the restorations of time had been complete. The little town had returned to what it was before the nineteenth century. The long rows of small houses had gone, like a healed rash, as though they had never been; and on all sides of the few buildings that clustered round the church and to the north of it, grazing land stretched out unbroken, save here and there by rude and overgrown walls of piled bricks. On this narrow platform, which fell away rapidly on the right hand and on the left, the troops were bivouacking, huddled in little clusters around miserable fires or dancing about to keep themselves warm.

Jeremy’s eye ran from one end of the prospect to the other and back again, until he became conscious that somebody was standing at his elbow waiting for him to turn. He turned accordingly and found the Canadian, whose customary barbaric fineness of dress seemed to have been enhanced for the occasion by a huge dull red tie and a dull red handkerchief pinned carelessly in a bunch on the brim of his hat.

“What do you think of them?” asked Thomas Wells in his hard, incisive tones, indicating the shivering soldiers by a jerk of his head.

“I’ve not seen enough of them to think anything,” Jeremy answered defensively. “I dare say they’re not at their best now.”

“Poor stuff!” snapped the Canadian, between teeth almost closed. “Poor stuff at the best. I could eat them all with half of one of our regiments. Yes…” he continued, drawling as though the words had an almost physical savor for him, “if I got among them with two or three hundred of my own chaps, I bet we wouldn’t leave a live man anywhere within sight in half-an-hour. We’d cut all their throats. It’d be like killing sheep.”

Jeremy shuddered involuntarily and moved a step away. “Where’s all the rest of the army?” he asked.

“The rest? There isn’t any rest. You can see all there is of it.”

“But surely…” Jeremy began, and paused.

The Canadian laughed with malicious and evil amusement. “They’re not great at fighting here,” he said. “If they’d taken only those that wanted to come there’d be you and me and the Speaker. And they wouldn’t take people from the fields — or not many at all events. And there’s nobody come from Gloucestershire or the West, though the Speaker sent to them twice. The farmers over there are waiting to see what happens. They don’t want to quarrel with the bosses that buy their wool. No, it’s not a big army — eight thousand at most. And yet,” he went on reflectively, “it’s more than I had when I tore the guts out of Boston. I tell you, we got into that city….”

“Yes,” Jeremy interrupted him nervously, not desiring in the least to know what happened in Boston, “but how many have the northerners got?”

“Oh, not many more, by all accounts,” the Canadian answered airily. “Ten or twelve thousand, I reckon. Oh, yes, we’re going to get whipped all right, but I’ve got a good horse, and I expect the Chairman will want to stand well with my dad. Yes —I’ve got a good horse, a lot better than yours.” As he spoke he glanced at Jeremy’s tubby nag, and his narrow mouth stretched again in the same smile of evil amusement.

Jeremy’s heart sank. But, as he was wondering whether his dismay was betrayed by his face, a gentle bustle rose around them.

“We’re marching off,” cried the Speaker, as he strode by with the vigor of a boy of twenty. “Back to your — to your charge, Jeremy Tuft.”

It was not until the whole army was well on the road that Jeremy found himself sufficiently unoccupied to examine it carefully. His old men resumed the march, with, if anything, a little too much enthusiasm. They were extravagantly keen to show the twenty-first century what their guns could do; but in their anxiety to take their place on the battlefield they behaved, as Jeremy bitterly though unintelligibly told them, like a crowd of children scrambling outside the door of a Sunday-school tea. Even Jabez, whom he had chosen to act as a sort of second-in-command, danced about from wagon to wagon and gun to gun like the infant he was just, for the second time, becoming. A company of the ordinary soldiers, who, in accordance with plan, had been attached to the battery so that they might help in man-handling the guns, watched the excited gyrations of the old men in solemn silence. The march northwards out of the little town was well begun before Jeremy could feel sure that his own command was smoothly and safely in hand. As soon as he was satisfied he left it and rode on ahead to see what he could make of the army.

He had had little enough time to make himself familiar with the new methods of warfare. He had, in his rare, idle moments, questioned everybody he met who seemed likely to be able to tell him; but he found much the same uncertainty as to the deadliness of modern weapons as he dimly remembered to have existed in the long past year of 1914. The troops with whom he was riding to battle were armed, and had, many of them, been drilled; but what would be the effect of their arms and how their drill would answer in warfare no one knew, for they had never been tried. He formed himself, this gray and early morning, a most unfavorable impression of them.

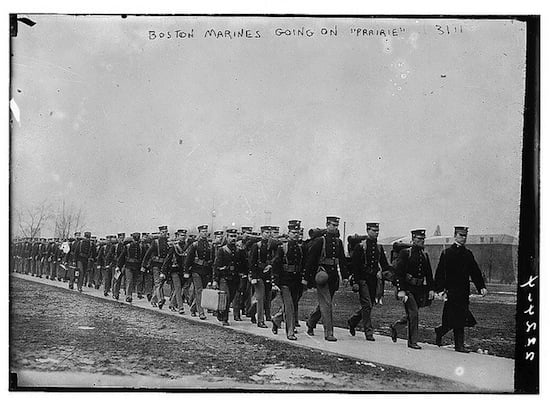

Their uniforms were shabby and shoddy, uncouth, loosely-cut garments, varying in shape and color. On their feet they wore rude rawhide shoes or sandals and round their legs long strips of rag were shapelessly wrapped. Their bearing was execrable. They made only the emptiest pretense at march discipline, they slouched and shuffled, left the ranks as they pleased, held themselves and their arms anyhow. The officers were for the most part young men of good family who had been appointed to commands only during the past four or five days. A few, those who had trained the army in times of peace, were soldiers of fortune, who had been drawn by the Speaker’s lavish offers to them from the wars in the Polish Marches and in the Balkans, from every place where a living could be earned by the slitting of throats. They were old, debauched, bloated and lazy, low cunning peeping out from their eyes like the stigma of a disease. They looked much better suited to any kind of private villainy than to the winning of battles; and the contingents under their command had an appearance of hang-dog shiftiness rather than the sheepish reluctance of the rest.

Not much more than half the army was provided with rifles; and these, as Jeremy knew, were hardly to be described as weapons of precision. The rest had a sort of pikes; or some had cutlasses, some bayonets lashed to the ends of poles. The rifles reminded Jeremy a little of those of his earlier experience, but suffering from the thickening and clumsy degeneration of extreme old age. They had no magazines: the workshops were not equal to the production of a magazine that would not result in fatal stoppages. The breech-loading action was retained and was frequently efficient, so Jeremy learnt, for as many as twenty-five rounds. After that it was liable to jam altogether and, at the best, permitted only a reduced rate of fire. The range was supposed to be five hundred yards, but the best and most careful marksman could rarely at that distance hit a target the size of a man. Jeremy calculated that the effective range was not more than two hundred yards at the outside; and he thought that very little damage would be done at more than half that distance. As he rode along by the side of the marching regiments, he observed the pikes and cutlasses, and the sheathless bayonets which hung at the belts of the riflemen, and wondered what would happen when it came to close fighting. Neither the carriage nor the expressions of the men inspired him with confidence. Many of them, especially the new recruits, haled in at the last moment from field and farm, were healthy, sturdy fellows; but, unless he was mightily mistaken, an abhorrence of fighting was in their blood. He himself had only a blunderbuss of a double-barreled pistol, which reminded him of the highwaymen stories of his boyhood, and a most indifferent horse….

He reached the end of this train of thought, found it disagreeable, and paused, as it were, on the edge of an abyss. Then he drew in his horse against the roadside, halted, and let the column march past him. At the end came his battery, plodding along with more enthusiasm than all the rest of the army put together. Jabez, perched beside the driver on the seat of the first wagon, hailed his reappearance with delight, scrambled down and ran to him, putting one hand on his stirrup.

“Well, Jabez,” said Jeremy kindly, as he might have addressed an affectionate dog, “and how do you think we are getting along?” As he spoke he tapped his horse lightly and began to move on again. Jabez hopped by his side, ecstatically proclaiming in cracked tones that he expected the beautiful guns to blow the damned Yorkshiremen to hell. The only thing that annoyed him was this great press of useless infantry in front of them. They might be useful enough, he felt, to drag the guns into position and perhaps to remove what was left of the enemy when he had done with them. But he certainly envisaged the coming battle as a contest between the army of the north on the one hand and two doubtful sixty-pounder guns on the other. Jeremy listened to him tolerantly, as if in a dream. Faint wreaths of mist were rising up from the fields all around them and scattering into the sparkling air. The tramp of the soldiers sounded heavy and sodden, a presage of defeat.

Far ahead Jeremy could see the column steadily but slowly following the slight curves in the road. Right at the van, as he knew, though they were out of his sight, were the Speaker and his staff —Thomas Wells, on the swift horse to which he trusted, close at the old man’s right hand. Somewhere just behind them was Roger Vaile, who, like many of the clerks in the Treasury, had chosen to be a trooper in the cavalry and had obtained admission to the Speaker’s own guard. Miles away in the rear of the army — was the Lady Eva, doubtless asleep; and around her, who was now to him the one significant point in it, London, asleep or waking, awaited the issue of the struggle. Jeremy felt terribly alone. This was very different from being in charge of two guns out of some five hundred or so bombarding the German front line before a push. An unexpected wave of lassitude came over him, and, defeat seeming certain, he wished that he could be done with it all at once.

As he sagged miserably in the saddle, a sudden check ran down the column, followed by an ever-increasing babel of whispered conjectures. The men behaved as infantry suddenly halted on the march always have done. They were divided between pleasure at the relief and a suspicion that something untoward had happened out of sight in front of them. They murmured to one another, unceasingly and eloquently, that their leaders were born fools and were taking them into a death-trap. But the check continued and no certain orders came down; and at last Jeremy rode forward, so that he might pass a slight rise in the ground and see what had happened. When he did so he found that the head of the column was already slowly deploying on both sides of the road.

“We’ve begun,” he murmured sharply to himself, and stayed a moment hesitating. Then, as he remembered that he had not yet heard a single shot, he spurred his horse on to make further enquiries. He found the Speaker, Thomas Wells, and two or three others just leaving the road by a farm-track to gain the top of a little mound close by.

The old man greeted him with a boyish wave of the hand. “There they are!” he called out, while Jeremy was still some yards away; and, following the sweep of his arm, Jeremy saw on the forward slope of a hill, about half-a-mile off, a flurry of horsemen plunging wildly about together. It looked at first like a rather crowded and amateurish game of polo; but, while he watched, he saw the sun sparkling again and again on something in the crowded mass. Then a body fell inertly from the saddle and a riderless horse galloped off over the hill. A minute later a few riders extricated themselves and smartly followed it.

“There they are!” said the Speaker again, this time in a quieter voice. The greater body of horsemen was now cantering back; and, before they had covered half the distance, a few scattered parties of infantry began to appear on the low crest above. Shots were fired here and there. The reports came over, dull and vague, against a contrary breeze.

“I must go back to my guns,” Jeremy gasped breathlessly. “I must go back.” He turned his horse and began to gallop lumberingly along the fields beside the road.

“Goo-ood luck to you!” came after him in a high-pitched mocking yell from the Canadian.

In a minute he had reached the battery. When he pulled up there he had to spend the best part of five minutes calming Jabez and his men, who wished to drag the guns incontinently into the next field and let them off at random over the slope before them. By liberal cursing he subdued the enraged ancients and got them at a sedate pace past the infantry immediately in front, who were in reserve and had not yet received orders to proceed. When he reached the top of the rise again he found that the whole of the enemy’s line had come into sight. It stretched out on both sides of the road, and its left flank seemed to be resting on a wood. It had ceased in its advance; and across its front a body of cavalry was riding slow and unmolested.

The sound of firing broke out again and increased rapidly. From the almost hidden line of the Speaker’s troops, and from the enemy on the opposite slope, black puffs of smoke arose, looking solid and sharply defined in the clear air. They drifted away, melting slowly as they went. Jeremy suffered a spasm of panic and haste. The struggle was beginning; and in a minute or two he must bring his guns into position and fire them. He dreaded lest the battle should be suddenly over and lost before he could let off a single round, lest he should never get even the slender chance, which was all that he could hope for. In that moment his faculties stopped dead, and he did not know what to do. But, as rapidly, the seizure passed, and he halted the battery while he rode out into the field on the right to find a position for the guns. Presently he came upon a little shallow dip, which would, in case of necessity, give cover from an attack by riflemen, while leaving to the guns a clear field of fire. He went back to the road and gave his orders.

Jabez and his companions began at once to behave like puppies unchained. They turned the gun-teams and urged them recklessly off the road with complete disregard of the ground they had to cover. “Steady, Jabez, steady!” Jeremy shouted. “Look out for that —” But before he could finish, the first gun had negotiated a most alarming slope, and the second was hard upon it. At the end of ten minutes’ confused sweating and bawling, the two guns were standing side by side, twenty yards apart, in the hollow he had chosen; and the crews, panting loudly with their mouths wide open, stood there also, looking at him and eagerly expecting the order to load and fire.

He had early abandoned all hope of using indirect fire from any kind of shelter: for the technical equipment of his men was plainly not equal to it. He had therefore been obliged to decide upon the use of open sights; and from the lip of this hollow he could see, he imagined, a reasonably large area of the battlefield. It stretched, so far as he could make out, from the woods on his right, which, where the front line ran, were closer to the road than here, to a vague and indiscernible point that lay a somewhat greater distance on the other side of the road. The Speaker’s men were some three-quarters of a mile in front of him, the enemy nearly half a mile beyond that. It appeared to Jeremy that the exchange of shots up to now had been no more than a symbolic expression of ill-will, since at that range it was obviously impossible for the antagonists to hit one another.

A feverish and exhaustive search during the week of preparation had not obtained for Jeremy the field-glasses which he had hoped might be lying in some corner, uninjured and forgotten; but it had at last brought forth a reasonably good pair of opera-glasses. With these at his eyes, he stood on the edge of his hollow, shifting uneasily from one foot to the other, and vainly searched the landscape for a target. His only chance, he told himself, was to catch a mass of the enemy somewhere in the open and to scatter them with a direct hit. If he could do this, he thought, the moral effect might be to dismay them, and to put heart into the Speaker’s troops. But he did not suppose that he could rout the whole army of the north with fifty rounds of a very feeble and uncertain kind of high explosive, which was all the ammunition he had been able to get together for the two guns. “If only we had shrapnel —” he was murmuring to himself; but then Jabez’s attempt at a time-fuse had been altogether too fantastic. “If only we had quick-firers… seventy-fives…” But things were as they were, and he must make the best of them.

But still no target presented itself. Neither line seemed to move; and, in fact, any considerable movement must have been instantly visible on that smooth, hardly broken stretch of pasture-land. This state of immobility continued for half an hour or so, during which Jeremy’s anxiety increased, relaxed, and increased again, until the alternation of moods became almost unbearable. Once, quite suddenly, the firing, which had grown slacker, broke out again violently on the right. It began with an attempt at volleys, but after a moment or two fell into irregularity and raggedness. Jeremy, scanning the ground with his opera-glasses, could find no cause for it. He attributed it to panic and was beginning to believe that the formidableness of the Yorkshire army had been much overrated. He had just let fall the glasses when he was disturbed by a touch at his elbow. He turned and saw Jabez, a stooped, shriveled figure that looked up at him with shining youthful eyes in a face absurdly old.

“Aren’t we going to let them off?” pleaded Jabez in wistful tones. “Aren’t we ever going to let them off? Just once — anywhere….” He swept a claw-like hand round the horizon, as though it was immaterial to him where the shot fell, so long as it was discharged. “It would frighten those fellers,” he added with cunning.

Jeremy reluctantly smiled. “We must wait till we can frighten them properly,” he answered, “and just at present I can’t see anything to fire at.”

“We sha’n’t ever get a chance,” wailed Jabez; and he lolloped mournfully back to the guns so as to be ready for the first order.

Intense quiet descended again upon the battlefield. Both sides seemed to be lying down in their lines, each waiting for the other to make a move. Jeremy uttered a short, involuntary laugh. This, he supposed, was what might be expected from a people so incredibly unused to warfare, but it was nevertheless a trifle ludicrous. He determined to ride forward again and consult with the Speaker.

He had mounted and ridden a hundred yards from the battery, when a second burst of firing broke out, this time apparently upon the left. The road, which ran along the crest of a slight ridge, would give him a better view, and thither he hastened. When he gained it he saw that on the extreme left the battle had indeed begun and, to all appearance, disastrously. A great body of Yorkshiremen was advancing in close formation, and already the Speaker’s troops were giving way, some throwing down their weapons, some firing wildly as they ran. Jeremy paused rigid for a second. It was as though what he saw touched only the surface of the brain and by that paralyzed all power of thought. Those scuffling, running, dark figures over there were fighting and being killed. They were fighting and being killed in the great contest between civilization and barbarism for the body of England; and barbarism, it seemed, was winning. But there was nothing impressive in their convulsed and ungainly actions. They were merely dark figures running about and scuffling and sometimes falling. Jeremy knew very well what it was that he saw, but he did not realize it. It did not seem real enough to make the intimate contact between perception and thought which produces a deed. Then suddenly his paralysis, which felt to him as though it had lasted a million years, was dissolved, and before he knew what he was doing he had turned and was galloping back to the battery at a speed which considerably astonished his horse.

“Get those guns out!” he yelled, with distorted face and starting eyes. “Get those guns —” His voice cracked, but already the old men were in a frenzy of haste, limbering up and putting in the teams. In a few moments, it seemed, they were all scurrying together over the field, Jabez clinging to Jeremy’s stirrup, flung grotesquely up and down by the horse’s lumbering stride, the guns tossed wildly to and fro on the uneven ground. They breasted the slight ridge of the road like a pack of hounds taking a low wall and plunged down together on the further side, men, guns, horses, wagons, all confused in a flying mass.

“My God!” Jeremy gasped to himself. “Any one would think we were horse-gunners. I wouldn’t have believed that it could be done.”

His own reflection sobered him, and, lifting himself in the saddle, he shouted to the insane mob around him: “Steady! Steady! Steady!” The pace slackened a little, and a swift glance round showed him that, by some miracle, no damage had been done. How these heavy guns and wagons, even with their double teams of horses, had been driven at such a speed over ground so broken and over the bank of the road was, he supposed, something he would never be able to explain; and this was least of all the moment for troubling about it. But the divine madness, which must have inspired men and animals alike, had now evaporated, and it was time to think what he must do. In another hundred yards he had made his way to the front of the battery and had halted it by an uplifted hand. Then first he was able to see how the situation had developed.

It had gone even worse than he had feared, and he had halted only just in time. So far as he could make out, the whole of the Speaker’s left flank had been driven back in confusion and was fighting, such of it? as yet stood, in little groups. Some of these were not more than three or four hundred yards in front of him. Complete ruin had failed to follow only because the Yorkshire troops had attacked in small force and were for the moment exhausted. But over where their first line had been he could see new bodies approaching to the attack. When he looked round for help he found that the Speaker’s army was engaged all along its length and that only a meager company of reserves was coming up, slowly and from a great distance.

His decision was rapidly made. Now, if ever, he had his chance of using his guns to demoralize the enemy, and if he could thus break up the attack, the position might yet be restored. It was true that here in the open he ran a mighty risk of losing the guns. The remnants of the enemy’s wave were not far off; and hardly anything in the way of defenders lay between him and them. But this only spurred him to take a further risk. He led the battery forward again to a convenient hollow, a few yards behind one of the still resisting groups, which was lodged in a little patch of gorse. And, just as the battery came up, a party of the enemy made a rush, driving the Speaker’s men back among the horses and wagons. There was a whirlwind moment, in which Jeremy was nearly thrown from his plunging horse. He had no weapon, but struck furiously with his fist into a face which was thrust up for a second by his bridle. Around him everything was in commotion, men shouting in deep or piping voices, arms whirling, steel flashing. And then miraculously all was quiet again and he calmed his horse. A few bodies lay here and there, some in brown, some in uniforms of an unfamiliar dark blue. They were like the line of foam deposited by the receding wave. Not far away, Jabez, surprised and bewildered, but unhurt, lay on his back, where he had been pushed over, waving his arms and legs in the air. Another of the old men had collapsed across the barrel of one of the guns and blood was spouting from his side. Beyond the battery a few of the infantrymen were standing, wild-eyed and panting, in attitudes of flight, unable to believe that their opponents had been destroyed. Further off still the company which had been attached to the guns, and which they had left behind in their wild rush, was coming up and had halted irresolutely to see what turn events would take.

Jeremy recovered his self-possession, and, with the help of the shaken but indomitable Jabez, got the guns into place and gave the order to load. Then himself he trained the first gun on a body of Yorkshire troops which was advancing in column over half a mile away. There followed a tense moment.

“Fire!” He cried the word in a trembling voice.

Jabez, with an air of ineffable pride, pulled the lanyard and all the old men at once leapt absurdly at the report. Over, far over! And yet the shell had at least burst, and through his glasses he could see the enemy waver and halt, obviously astonished by the new weapon. He ran to the other gun, trained it, and again gave the order to fire. It was short this time, and the smoke and dust of the explosion hid the mark. But when the air was clear again, Jeremy saw that the column had broken and was dispersing in all directions. Apparently the flying fragments of the shell had swept its leading ranks. The old men raised a quavering cheer, and Jabez, leaping with senile agility to an insecure perch on the gun-carriage, flourished his hat madly in the air.

Jeremy’s first feeling was one of relief that neither of the guns had blown up. He examined them carefully and was satisfied. When he resumed his survey of the field there was no target in sight. But the firing on the right was growing louder and, he thought, nearer. It was not possible to drag these guns from point to point to strengthen any part of the line that might happen to be in danger; and his despair overwhelmingly returned. He swept the ground before him in the faint hope of finding another column in the open. As he did so he suddenly became aware that he could just see round the left of the ridge on which the northern army had established itself; and, searching this tract, he observed something about a mile away, under the shade of a long plantation, that seemed significant. He lowered his glasses, wiped the lenses carefully, and looked again. He had not been mistaken. There, within easy range, lay a great park of wagons, which was perhaps the whole of the enemy’s transport.

Now, if it were possible, he exultantly reflected, fortune offered him a chance of working the miracle which the Speaker had demanded of him. He beckoned Jabez to his side, pointed out the mark and explained his intention. The ancient executed a brief, brisk caper of delighted comprehension, and together they aimed the two guns very carefully, making such allowances as were suggested on the spur of the moment by the results of the first shots. They were just ready when the noise of battle again clamorously increased on the right and urged them forward.

“It’s now or never, Jabez,” muttered Jeremy, feeling an unusual constriction of the throat that hindered his words. But Jabez only replied with an alert and bird-like nod of confidence.

“Fire!” Jeremy cried in a strangled voice. The lanyards were jerked, and Jeremy, his glasses fixed on the target, saw two great clouds spring up to heaven not far apart. Were they short? But when the smoke drifted away, he saw that they had not been short. Feverishly he made a slight adjustment in the aim, and the guns were fired again. Now one burst showed well in the middle of the enemy’s wagons, but the second did not explode. Jeremy was trembling in every muscle when he gave the order to load and fire for the third time. Was it that he only imagined a slackening, as if caused by hesitation, in the noise of the attack on the right? He could hardly endure the waiting; but when the third round burst he could hardly endure his joy. For immediately there leapt into the air from the parked wagons an enormous column of vapor that seemed to overshadow the entire battlefield, and hard after this vision came a deafening and reverberating explosion, which shook the ground where he stood.

“Got their ammunition!” he screamed, the tears pouring down his face. “There must have been a lot!” He reached out blindly for Jabez; and the old men of the battery observed their commander and his lieutenant clasping one another by the hands and leaping madly round and round in an improvised and frenzied dance of jubilation.

When the echoes of that devastating report died away, complete silence stole over the battlefield, as though heaven by a thundered reproof had hushed the shrill quarrels of mankind. It was broken by a thin cheering, which grew louder and increased in volume till the sky rang with it; and Jeremy, rushing forward to see, realized that everywhere within sight the Speaker’s men had taken heart and were falling boldly on their panic-stricken enemies.

NEXT WEEK: “Jeremy and Jabez had hastened into the midst of them before Jeremy was overtaken by a belated coolness of the reason. When the sobering moment came, he wished he had had the sense to keep out of this confused and murderous struggle, and at the same time he remembered that his only weapon was a pistol still strapped in its clumsy holster. He reached for it and began to fumble with the straps; but while he fumbled a desperate Yorkshireman, turning like a rat, pushed a rifle into his face and pulled the trigger.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.