The People of the Ruins (6)

By:

June 28, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the sixth installment of our serialization of Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After. New installments will appear each Thursday for 16 weeks.

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — in a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Not only have his fellow Londoners forgotten most of what humankind used to know, before civilization collapsed, but they don’t particularly care to re-learn any of it. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

Shanks’ post-apocalyptic novel, a pessimistic satire on Wellsian techno-utopian novels, was first published in 1920. In October, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The People of the Ruins, with an introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “She held out two fingers to him, a perplexing action; but it seemed from the stiffness of her arm that she did not expect him to kiss them. He shook and dropped them awkwardly and breathed a sigh of relief. Then he was able to examine the first lady of England and her surroundings, while, with much less interest and an expression of stupid aloofness, she examined him.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |15 |16

THE GUNS

During the days that immediately followed, the Speaker left Jeremy to make himself at home as best he could in the new world. For a time Jeremy was inclined to fear that by a single obstinacy he had forfeited the old man’s favor. He had been removed from the little room which he had first occupied to another, larger and more splendidly furnished, near the Speaker’s own apartments. But he had pleaded, with a rather obvious confidence in his right to insist, that he should be allowed to continue his friendship with Roger Vaile. Some obscure loyalty combined with his native self-will to harden him in this desire; and the Speaker was displeased by it. He had evidently had some other companion and instructor in mind.

“The young man is brainless, like all his kind,” he objected. “You will get no good from him.”

“But he did save my life. Why would he think of me if I forgot him now?”

“No man could have done less for you than he did. You ought not to let that influence you.”

The wrangle was short but too rapidly grew bitter. To end it Jeremy cried with a gesture of half-humorous despair, “Well, at least he is my oldest living friend.”

The Speaker shrugged his shoulders and gave way without a smile; but he seemed from this moment to have abandoned him to the company he thus wilfully chose. For the better part of a day Jeremy was pleased by his deliverance from a dangerous and uncomfortable old fanatic. Thereafter he fell to wondering, with growing intensity, what were now his chances of meeting again with the Speaker’s daughter.

When he rejoined Roger Vaile, that placid young man received him without excitement, and informed him that they might spend the next few days in seeing the sights of London. Jeremy’s great curiosity answered this suggestion with delight; and in his earliest explorations with Roger he found many surprises within a small radius. The first were in the great gardens of the Treasury, which, so far as he could make out, in the absence of most of the familiar landmarks, took in all St. James’s Park, as well as what had been the sites of Buckingham Palace and Victoria Station. Certainly, as he rambled among them, he came upon the ruins of the Victoria Memorial, much battered and weathered, and so changed in aspect by time and by the shrubs which grew close around it that for several moments it escaped his recognition.

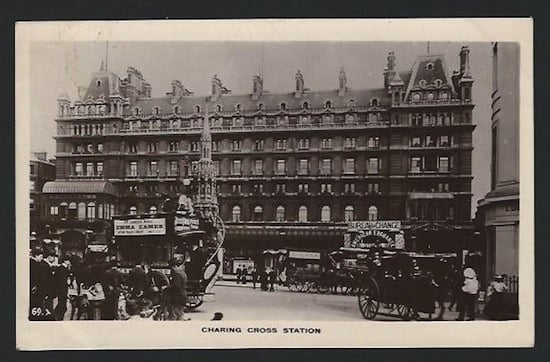

Outside the walls of the Treasury such discoveries were innumerable. Jeremy was astonished to find alternately how much and how little he remembered of London, how much and how little had survived. Westminster Bridge, looking old and shaky, still stood; but the Embankment was getting to be disused, chiefly on account of a great breach in it, how caused Roger could not tell him, in the neighborhood of Charing Cross. On both sides of this breach the great men who owned houses in Whitehall and the Strand were beginning to push their gardens down to the water’s edge. Indeed, as Jeremy learnt by his own observation and by close questioning of Roger, the growth of huge gardens was one of the conspicuous signs of the age.

There existed, it seemed, an aristocracy of some wealth descended mostly from those supporters of the first and second Speakers who had taken their part in putting down the Reds and restoring order more than a hundred years before. Where one of the old ruling families, great land-owners, great manufacturers, or great financiers had possessed a member of resolute and combative disposition, it had survived to resume its place in the new state. The rest were descendants of obscure soldiers of fortune. This class, of which Roger Vaile was an inconsiderable cadet, owned vast estates in some, though not in all, parts of the country. Here and there, as Jeremy surmised, where small-holders and market-gardeners had taken a firm grip, the landowning class had little power. But elsewhere it was strong, and drew great revenues from the soil, from corn, from tobacco, and from wool.

These revenues were spent by the ruling families —Roger called them “the big men”— in enlarging the gardens of their houses in London. They cared little to build. Houses stood in plenty, many even now unclaimed. But gradually the deserted houses were pulled down, their materials carted away and their sites elaborately planted. Jeremy walked in a great shrubbery of rhododendrons where Charing Cross Station had been and in a rose-garden over the deep-buried foundations of Scotland Yard. He observed that this fashion, which was becoming a mania, was creating again the old distinction between the City of London, which was still a trading center, and the City of Westminster, which was still the seat of government, although a revolutionary mob of somewhat doctrinaire inclinations had burnt down the Houses of Parliament quite early in the Troubles.

These excursions fascinated Jeremy, and he endeavored to make them useful by cross-examining Roger, as they walked about together, on the condition of society. But that typical man of far from self-conscious age had only scanty information to give. Even on the government of the country he was vague and unsatisfactory, though, when he had nothing better to do, he worked with the other clerks on the Speaker’s business. Jeremy sometimes saw him and his companions at work, copying documents in a laborious round-hand or making entries in a great leather-bound and padlocked ledger. He felt often inclined to re-introduce into a profession which had forgotten it the blessed principle of the card index; but, after consideration, he abstained from complicating this idyllically simple bureaucracy. Besides, there was no need for labor-saving devices. Clerks swarmed in the Treasury. A few years in the Speaker’s service was the proper occupation for a young man of good family who was beginning life; and the tasks which it involved weighed on them lightly.

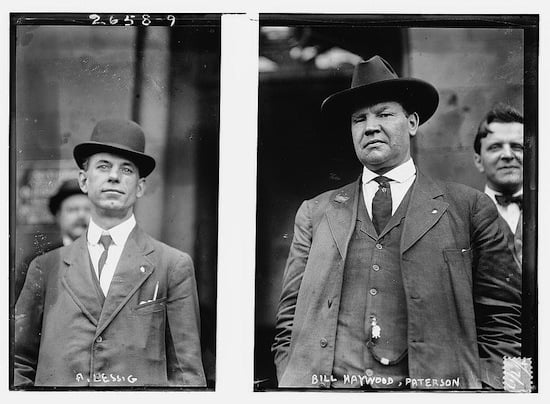

The business of government was not elaborate or complex. Apparently the provinces looked very much after themselves under the direction of a medley of authorities, whose titles and powers Jeremy could by no means compose into a system. He heard vaguely of two potentates, prominent among the rest and typical of them, the Chairman of Bradford, who seemed responsible for a great part of the north, and the President of Wales, who had a palace at Cardiff. Jeremy guessed that the titles of these “big men” had survived from all sorts of “big men” of his own time. The Chairman of Bradford for example might inherit his power from the chairman of some vanished revolutionary or reactionary committee, or perhaps even, since he was concerned in a peculiar way with the great weaving trade of Yorkshire, from that of an employers’ federation or a conciliation board. The President of Wales, whose relations with his tough, savage, uncouth miners were unusual, Jeremy suspected of being the successor of a trade union leader. The names and figures of these men lingered obscurely, powerfully, menacingly in his mind. The Speaker rarely interfered with them so long as they collected his taxes regularly and with an approach to completeness. And his taxes were moderate, for the public services were not exigent.

Jeremy caught a glimpse of one of these public services one day when Roger was taking him on a longer expedition than usual, to see the great northwestern quarter of old London. This district was one of the largest of those which, by some freak of chance, had escaped fire and bombardment and had been merely deserted, left to rot and collapse as they stood. Jeremy was anxious to examine this curiosity, and pressed Roger to take him there. It was when they were walking between the venerable and dangerously leaning buildings of Regent Street that they passed a column of brown-clad men on the march.

“Soldiers!” cried Jeremy, and paused to watch them go by.

“Yes, soldiers,” Roger murmured with a smile of good-natured contempt, trying to draw him along. But Jeremy’s curiosity had been aroused. He suddenly remembered, and then closed his lips on an enigmatical remark which the Speaker had made about guns; and he insisted on staying where he was until the regiment had gone out of sight. Their uniforms, an approximation to khaki, yet of a different shade, their rifles, clumsy and antiquated in appearance, their feet wrapped in rags and shod with raw-hide sandals, combined with their shambling, half-ashamed, half-sulky carriage to give them the air of a parody on the infantry of the Great War.

“Whom do they fight?” he asked abstractedly, still standing and gazing after them.

“No one,” Roger answered, with the same expression of contemptuous tolerance. “They are good for nothing; there has been no war in England for a hundred years.”

“But are there no foreign wars?”

“None that concern us.” And Roger went on to explain in an uninterested and scrappy manner that there was always fighting somewhere on the Continent, that the Germans and the Russians and the Polish were forever at one another’s throats, that the Italians could not live at peace with one another or with their neighbors on the Adriatic, and that the peoples of Eastern Europe seemed bent on mutual extermination. “But we never interfere,” he said. “It isn’t our business, though sometimes the League tries to make out that it is. And we need no army. It’s a fad of the Speaker’s, though he could always get Canadians if he wanted them.”

“The League? Canadians?” Jeremy interjected.

“Yes; the Canadian bosses hire out armies when any one wants them. They do say that that ruffian who is staying with the Speaker came over for some such reason. But I can’t see why we should want Canadians.”

“But you said… something… the League?”

“Oh, the old League!” Roger answered carelessly. “Surely that existed in your time, didn’t it? I mean the League of Nations.” And, as Jeremy said nothing, he continued: “You know, they sit at Geneva and tell every one how to manage his own affairs. We take no notice of them, except that we send them a contribution every year. And I don’t know why we should do even that. The officials are always all Germans… so close, you know…”

Jeremy fell into a profound reverie, out of which he presently emerged to ask, “Does your army have any guns… cannon, I mean?”

Roger shook his head. “You mean the sort of big gun that used to throw exploding shells. No; I don’t believe there’s such a thing left in the world. I never, heard of one.”

In order to draw Jeremy away from his meditations in Regent Street, Roger had taken him by the elbow, and from that had slipped his arm into Jeremy’s own. They walked along together in an amicable silence. Unexpected and violent events had drawn these two young men into a friendship which otherwise they would never have chosen, but which was perhaps not more arbitrary and not less real than the love of the mother for the child. Though their minds were so dissimilar, yet Jeremy felt a sort of confidence and familiarity in Roger’s presence; and Roger took a queer pride in Jeremy’s existence.

The district into which they entered when they got beyond the wilderness that had been Regent’s Park was a singular and striking reminder of the time when London was a great and populous city. Every stage of desolation and decay was to be seen in that appalling tract, which had lost the trimness and prosperity of its flourishing period without acquiring the solemn and awful aspect of nobler ruins. Every scrap of wood and metal had long been torn from these slowly perishing houses. Some had collapsed into their own cellars and were gradually being covered over. Some, which had been built of less enduring bricks, seemed merely to have melted, leaving only faint irregularities on the surface of the ground. Others stood gaunt and crazily leaning, with ragged staring gaps where the windows had been. Even as they passed one of these they heard the resounding collapse of a wall they could not see, while the outer walls heaved visibly nearer to ruin.

And here and there enterprising squatters had cleared large spaces, joining up the old villa-gardens into fair-sized fields. These people lived in rude huts, made of old timbers and rough heaps of brickwork, in corners of their clearings. Some distaste or horror seemed to keep them from the empty houses in the shadow of which they dwelt. Jeremy saw in the fields bowed laborious figures wrapped in rags which forbade him to say whether they were men or women, and troops of dirty, half-naked children. Roger followed the direction of his glance and said that the squatters among the deserted houses were people little better than savages, who could not get work in the agricultural districts or had mutinously deserted their proper employers.

Jeremy shuddered and went on without replying. The plan of these old streets was still recognizable enough for him to lead the way, as if in a dream, through St. John’s Wood to Swiss Cottage. Here they had to scramble across a tumbled ravine, which was all that was left of the Metropolitan Railway, and up the steep rise of FitzJohn’s Avenue to the little village of Hampstead clinging isolated on the edge of the hill. As they came into the village, Jeremy drew Roger into a side-track which he recognized, from one drooping Georgian house standing lonely there, as what he had known under the name of Church Row. The church remained, and beyond it Jeremy could see a farm half-hidden among trees. But he went no further. He turned his face abruptly southwards and stayed, gazing across London in that moment of perfect clearness which sometimes precedes the twilight of early summer.

For a moment, what he saw seemed to be what he had always known. At this distance the slope below seemed still to be covered with houses, and showed none of the hideousness of their decay. Farther out, in the valley, rose the spires and towers of innumerable churches, and beyond them came the faint blue line of the Surrey hills. But as he gazed he realized suddenly the greater purity of the air, the greater beauty of the view. London blackened no longer all the heaven above it, and the green gaps in the waste of buildings were larger and greener. Almost he thought he saw a silver line where the Thames should have been; but perhaps he imagined this, though he knew that the river was no longer dark and foul.

In his joy and contentment at the lovely scene he began to speak to Roger in a rapt, dreamy voice, as though he were indeed the mouthpiece and messenger of a less fortunate time. “You are happier than we were,” he said, “though you are poorer. Your air is clean, you have room, you live at peace, you have time to live. But we were forced to live in thick, smoky air; we fought and quarreled, and disputed. The more difficult our lives became, the less time we had for them. This age seems to me,” he continued, warming to his subject and ignoring Roger’s placid silence, “like a man who has been walking at full speed on a long dusty road, only trying to see how many miles he can cover in a day. Suddenly he grows exhausted and stops. I have done it. I can remember how delicious it was to lie down in a field off the road, to let the business all go, not to care where one got to or when. It was this peacefulness we should have been aiming at all the time, only we never knew….” Roger’s silence at last stopped him, and he turned to see what his companion was thinking. The expression of trouble on Roger’s face brought up a question on his own.

“It has just occurred to me,” Roger said slowly and reluctantly, “that it will be quite dark before we can get through all those houses….” He paused and shivered slightly. “I don’t quite like…”

They set off homewards, and darkness overtook them in the middle of Finchley Road. Roger did not speak again of his fears. Jeremy could not determine whether they were of violent men or of dead men. But he felt their presence. Roger, hardly spoke or listened until they were once again in inhabited streets.

It was on the following morning that the Speaker again sent for Jeremy.

Jeremy answered the second summons with a little excitement but with a heart more at rest than on the first occasion. He found the Speaker leaning at his open window, his head thrust out, his foot tapping restlessly on the ground. It was some moments before the abstracted old man would take any notice of his visitor. When he did so, he turned round with an air of restless and forced geniality.

“Well, Jeremy Tuft,” he cried, rubbing his hands together, “and have you learnt much from your friend?”

Jeremy replied stolidly that Roger had answered one way or another all the questions he had had time to ask. Some instinct kept him to his not very candid stubbornness. He was not going to be bullied into deserting Roger, of whose intellectual gifts he had nevertheless no very high opinion.

But the Speaker nodded without apparent displeasure. “And now you know all about our affairs?” he enquired.

Jeremy, still stolidly, shook his head but made no other answer. The Speaker suddenly changed his manner and, coming close to Jeremy, took him caressingly by the arm. “I know you don’t,” he murmured in a voice full of cajolery. “But tell me — you must have seen enough of our people — what do you think of them? What do you think can be done with them?” He leant slightly back and regarded the silent young man with an expression of infinite cunning. Then, as he got no response, he went on: “Tell me, what would you do if you were in my place — you, a man rich with all the knowledge of a wiser time than this? How would you begin to make things better?”

“I don’t know… I don’t know…” Jeremy cried at last, almost pathetically. “I can’t make these people out at all.” And, with that, he felt restored in his mind the former consciousness of an intellectual kinship between him and the old Jew.

But the Speaker continued with his irritating air of a ripe man teasing a green boy. “You remember the time when the whole world was full of the marvels of science. We suffered misfortune, and all the wise men, all the scientists, perished. But by a miracle you have survived. Can you not restore for us all the civilization of your own age?”

Jeremy frowned and answered hesitatingly. “How can I? What could I do by myself? And anyway, I was only a physicist. I know something about wireless telegraphy…. But then I could do nothing without materials, and at best precious little single-handed.” He meditated explaining just how much one man could know of the working of twentieth-century machinery, opened his mouth again and then closed it. He strongly suspected that the Speaker was merely fencing with him. He felt vaguely irritated and alone.

The old man dropped Jeremy’s arm, spun his great bulk round on his heel with surprising lightness and paced away to the other end of the room. There he stood apparently gazing with intent eyes into a little mirror which hung on the wall. Jeremy stayed where he had been left, forlorn, perplexed, hopeless, staring with no expectation of an answer at those huge, bowed, enigmatic shoulders. He was almost at the point of screaming aloud when the Speaker turned and said seriously with great deliberation:

“Well, I am going to show you something that you have not seen, something that not more than twenty persons know of besides myself. And you are going to see it because I trust you to be loyal to me, to be my man. Do you understand?” He did not wait for Jeremy’s doubtful nod, but abruptly jerked the bell-pull on the wall. When this was done they waited together in silence. A servant answered the summons; and the Speaker said: “My carriage.” The carriage was announced. The silence continued unbroken while they settled themselves in it, in the little enclosed courtyard that had once been Downing Street. It was not until they were jolting over the ruts of Whitehall that Jeremy said, almost timidly:

“Where are we going?”

“To Waterloo,” the Speaker answered, so brusquely that Jeremy was deterred from asking more, and leant back by his companion to muster what patience he could.

He had already been to Waterloo under Roger’s guidance. It was the station for the few lines of railway that still served the south of England; and they had gone there to see the train come in from Dover. But it had been so late that Roger had refused to wait any longer for it, though Jeremy had been anxious to do so. They had seen nothing but an empty station, dusty and silent. At one platform an engine had stood useless so long that its wheels seemed to have been rusted fast to the metals. Close by a careless or unfortunate driver had charged the buffers at full speed and crashed into the masonry beyond. The bricks were torn up and piled in heaps; but the raw edges were long weathered, and some of them were beginning to be covered with moss. The old glass roof, which he remembered, was gone and the whole station lay open to the sky. Pools from a recent shower glistened underfoot. Here and there a workmen sat idle and yawning on a bench or lay fast asleep on a pile of sacks.

This picture returned vividly to Jeremy as he rode by the Speaker’s side. It seemed to him the fit symbol of an age which had loosened its grip on civilization, which cared no longer to mend what time or chance had broken, which did not care even to put a new roof over Waterloo Station. He reflected again, as he thought of it, that perhaps it did not much matter, that the grip on civilization had been painfully hard to maintain, that there was something to be said for sleeping on a pile of sacks in a sound part of the station instead of repairing some other part of it. “We wretched ants,” he told himself, “piled up more stuff than we could use, and though the mad people of the Troubles wasted it, yet the ruins are enough for this race to live in for centuries. And aren’t they more sensible than we were? Why shouldn’t humanity retire from business on its savings? If only it had done it before it got that nervous breakdown from overwork!”

He was aroused by the carriage lurching into the uneven slope of the approach. The squalor that had once surrounded the great terminus had withered, like the buildings of the station itself, into a sort of mitigated and quiescent ugliness. As, at the Speaker’s gesture, he descended from the carriage, he saw a young tree pushing itself with serene and graceful indifference through the tumbled ruins of what had once been an unlovely lodging-house. A hot sun beat down on and was gradually dispelling a thin morning haze. It gilded palely the gaunt, harsh lines of the station that generations of weathering could never make beautiful.

The Speaker, still resolutely silent, led the way inside, where their steps echoed hollowly in the empty hall. But the echoes were suddenly disturbed by another sound; and, as they turned a corner Jeremy was enchanted to see a long train crawling slowly into the platform. It slackened speed, blew off steam with appalling abruptness and force, and came to a standstill before it had completely pulled in. Jeremy could see two little figures leaping from the cab of the engine and running about aimlessly on the platform, half hidden by the still belching clouds of steam.

“Another breakdown!” the Speaker grunted with sudden ferocity; and he turned his face slightly to one side as though it pained him to see the crippled engine. Jeremy would have liked to go closer, but dared not suggest it. Instead he dragged, like a loitering child, a yard or two behind his formidable companion and gazed eagerly at the distant wreaths of steam. But he only caught a glimpse of a few passengers sitting patiently on heaps of luggage or on the ground, as though they were well used to such delays in embarkation. He ran after his guide, who had now passed the disused locomotive rusted to the rails, and was striding along the platform and down the slope at the end, into a wilderness of crossing metals. Here and there in this desert could be seen a track bright with recent use; but it was long since many of them had known the passage of a train. In some cases only streaks of red in the earth or sleepers almost rotted to nothing showed where the line had been. They passed a signal-box: a man sat placidly smoking at the top of the steps outside the open door. They went on further; into the desolation that surrounds a great station, here made more horrible by the absence of movement, by the pervading air of ruin and decay.

When they had walked a few hundred yards from the end of the platform, they came to a group of buildings, which, in spite of their dilapidation, had about them a certain appearance of still being used. “The repairing sheds,” said the Speaker, pointing through an open door to a group of men languidly active round what looked like a small shunting-engine. Then he entered a narrow passage between two buildings.

As they went down this defile, a noise of hammering and another noise like that of a furnace grew louder and louder; and at the end of the passage there was a closed door. The Speaker paused and looked at Jeremy with a doubtful expression, as though for the last time weighing his loyalty. Then he seized a hanging chain and pulled it vigorously. A bell clanged, harsh and melancholy, inside the building. Before the last grudging echoes had died away, there was a rattling of bolts and bars, and the door was opened to the extent of about a foot. An old man in baggy, blue overalls, with dirty, white hair, and a short, white beard, stood in the opening, blinking suspiciously at the intruders.

He stood thus a minute in a hostile attitude, ready to leap back and slam the door to again. But all at once his expression changed, he shouted something over his shoulder and became exceedingly respectful. As Jeremy followed the Speaker past him into the black interior of the shed he bowed and muttered a thick incoherent welcome in a tongue which was hardly recognizable as English, so strange were its broad and drawling sounds.

Inside, huge shapes of machinery were confused with thick shadows, which jerked spasmodically at the light from an open furnace. It was some moments before Jeremy got the proper use of his eyes in the murky air of the shed. When he did he received an extraordinary impression. A group of old men, all in the same baggy blue overalls as the first who opened the door, had turned to greet them and were bowing and shuffling in an irregular and comical rhythm. Round the walls the obscure pieces of mechanism resolved themselves into all the appurtenances of a foundry, hammers, lathes and machines for making castings, in every stage of neglect and disrepair, some covered with dust, some immovably rusted, some tilted drunkenly on their foundation plates, some still apparently capable of use. And behind the gang of old men, raised on trestles in the middle of the floor, were two long and sinister tubes of iron.

The Speaker stood on one side, fixing on Jeremy a look of keen and exultant enquiry. Jeremy advanced towards the two tubes, a word rising to his tongue. He had not taken two steps before he was certain.

“Guns!” he whispered in a tense and startled voice.

“Guns!” replied the Speaker, not repressing an accent of triumph.

Jeremy went on and the old men shuffled on one side to make way for him, clucking with mingled agitation and pride. He examined the guns with the eye of an expert, ran his fingers over them, peered down the barrels, and rose with a nod of satisfaction. They seemed to be wire-wound, rifled, breech-loading guns, of which only the breech mechanism was missing.

They resembled very closely the sixty-pounders of his own experience, though they were somewhat smaller. When the breech mechanism was supplied, they would be efficient and deadly weapons of a kind that he well knew how to handle.

NEXT WEEK: “Once they had been obtained, they had slaved for years with senile docility to satisfy the demands which the Speaker’s senile and half-lunatic enthusiasm made on their disappearing knowledge. Somehow he had created in them a queer pride, a queer spirit of endeavor. That grotesque chorus of ancients had become inspired with a single anxiety, to create before they perished a gun which could be fired without instantly destroying those who fired it.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, serialized between January and April 2012; Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), serialized between March and June 2012; Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, serialized between April and July 2012; and H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, serialized between March and August 2012.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.