The Clockwork Man (13)

By:

June 12, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the thirteenth installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

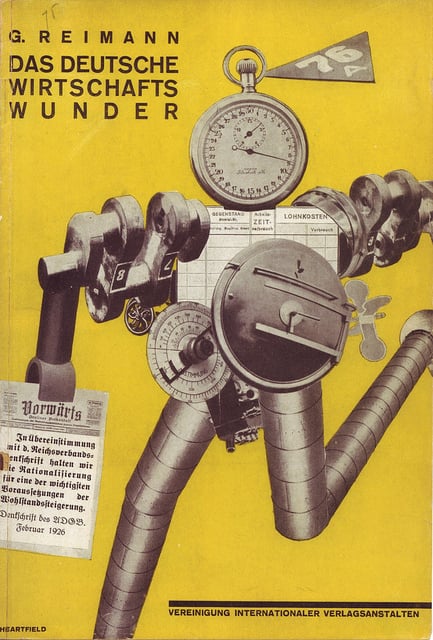

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village. Comical yet mind-blowing hijinks ensue.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R.

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man. Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s.” — Anatomy of Wonder (1995)

In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9. Newitz is also author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013) and Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (2006).

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

“There was a man,” continued the Curate, in ancient-mariner-like tones, “at the Templars’ Hall. I thought he was the conjurer, but he wasn’t — at least, I don’t think so. He did things — impossible things —”

“What sort of things,” enquired the Doctor, slowly, as he listened to the Curate’s heart.” You must make an effort to steady yourself.”

“He — he made things appear,” gasped the Curate, with a great effort, “out of nowhere — positively.”

“Well, isn’t that what conjurers are supposed to do?” observed the Doctor, blandly.

But the Curate shook his head. Fortunately, in his professional character there was no need for the Doctor to exhibit surprise. On the contrary, it was necessary, for his patient’s sake, to exercise control. He leaned against the mantelpiece and listened attentively to the Curate’s hurried account of his encounter with the Clockwork man, and shook his head gravely.

“Well, now,” he prescribed, “complete rest for a few days, in a sitting posture. I’ll give you something to quieten you down. Evidently you’ve had a shock.”

“It’s very hard,” the Curate complained, “that my infirmity should have prevented me from seeing more. The spirit was willing but the flesh was weak.”

“Very likely,” the Doctor suggested, “someone has played a trick upon you. Perhaps your own nerves are partly to blame. Men with highly strung nerves like you are very liable to — er — hallucinations.”

“I wonder,” said the Curate, grasping the edge of his chair, “I wonder, now, if Moses felt like this when he saw the burning bush.”

“Ah, very likely,” rejoined the Doctor, glad of the opportunity to enforce his analogy. “There’s not the least doubt that many so-called miracles in the past had their origin in some pathological condition improperly understood at the time. Moses probably suffered from some sort of hysteria — a sort of hypnosis. Even in those days there was the problem of nervous breakdown.”

His voice died away. The Curate was not actually shaking his head, but there was upon his features an expression of incredulity, the like of which the Doctor had not seen before upon a human face, for it was the incredulity of a man to whom all arguments against the incredible are in themselves unbelievable. It was a grotesque expression, and with it there went a pathetic fluttering of the Curate’s eyelids, a twitching of his lips, a clasping of small white hands.

“I’m afraid your explanation won’t hold water,” he rejoined. “I can’t bring myself not to believe in what I saw. You see, all my life I have been trying to believe in miracles, in manifestations. I have always said that if only we could bring ourselves to accept what is not obvious. My best sermons have been upon that subject: of the desirability of getting ourselves into the receptive state. Sometimes the Vicar has objected. He seemed to think I was piling it on deliberately. But I assure you, Doctor Allingham, that I have always wanted to believe — and, in this case, it was only my infirmity and my unfortunate nervousness that led me to lose such an opportunity.”

The Doctor drew himself up stiffly, and just perceptibly indicated the door. “I think you need a holiday,” he remarked, “and a change from theological pursuits. And don’t forget. Rest, for a few days, in a sitting posture.”

“Thank you,” the Curate beamed, “I’m afraid the Vicar will be very annoyed, but it can’t be helped.”

They were in the hall now, and the Doctor was holding the street door open.

“But it happened,” the Curate whispered. “It really did happen — and we shall hear and see more. I only hope I shall be well enough to stand it. We are living in great days.”

He hovered on the doorstep, rubbing his hands together and looking timidly up at the stars as though half expecting to see a sign. “It distressed me at first,” he resumed, “because he was such an odd-looking person, and the whole experience was really on the humorous side. I wanted to laugh at him, and it made me feel so disgraceful. But I’m quite sure he was a manifestation of something, perhaps an apotheosis.”

“Don’t hurry home,” warned the Doctor. “Take things quietly.”

“Oh, yes, of course. The body is a frail instrument. One forgets that. So good of you. But the spirit endures. Good night.”

He glided along the deserted High Street. The Doctor held the door ajar for a long while and watched that frail figure, nursing a tremendous conviction and hurrying along, in spite of instructions to the contrary.

The Clockwork Man Explains Himself

I

Late that evening the Doctor returned from a confinement case, which had taken him to one of the outlying villages near Great Wymering. The engine was grinding and straining as the car slowly ascended a steep incline that led into the town; and the Doctor leaned forward in the seat, both hands gripping the wheel, and his eyes peering through the wind-screen at the stretch of well-lit road ahead of him.

He had almost reached the top of the hill, and was about to change his gear, when a figure loomed up out of the darkness and made straight for the car. The Doctor hastily jammed his brake down, but too late to avert a collision. There was a violent bump ; and the next moment the car began running backwards down the hill, followed by the figure, who had apparently suffered no inconvenience from the contact.

Aware that his brakes were not strong enough to avert another disaster, the Doctor deftly turned the car sideways and ran back-wards into the hedge. He leapt out into the road and approached the still moving figure.

“What the devil!”

The figure stopped with startling suddenness, but offered no explanation.

“What are you playing at?” the Doctor demanded, glancing at the crumpled bonnet of his car. “It’s a wonder I didn’t kill you.”

And then, as he approached nearer to that impassive form, staring at him with eyes that glittered luridly in the darkness, he recognised something familiar about his appearance. At the same moment he realised that this singular individual had actually run into the car without apparently incurring the least harm. The reflection rendered the Doctor speechless for a few seconds; he could only stare confusedly at the Clockwork man. The latter remained static, as though, in his turn, trying to grasp the significance of what had happened.

It occurred to the Doctor that here was an opportunity to investigate certain matters.

“Look here,” he broke out, after a collected pause, “once and for all, who are you?”

A question, sharply put, generally produced some kind of effect upon the Clockwork man. It seemed to release the mechanism in his brain that made coherent speech possible. But his reply was disconcerting.

“Who are you?” he demanded, after a preliminary click or two.

“I am a doctor,” said Allingham, rather taken back, “a medical man. If you are hurt at all —”

An extra gleam of light shone in the other’s eye, and he seemed to ponder deeply over this statement.

“Does that mean that you can mend people?” he enquired, at last.

“Why yes, I suppose it does,” Allingham admitted, not knowing what else to say.

The Clockwork man sighed, a long, whistling sigh. “I wish you would mend me. I’m all wrong you know. Something has got out of place, I think. My clock won’t work properly.”

“Your clock,” echoed the doctor.

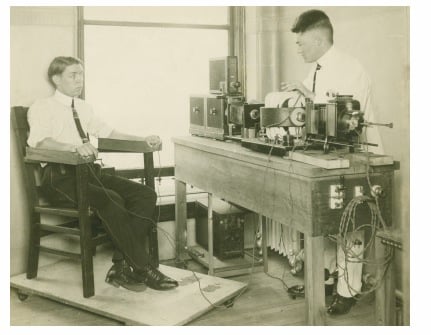

“It’s rather difficult to explain,” the Clockwork man continued, “but so far as I remember, doctors were people who used to mend human beings before the days of the clock. Now they are called mechanics. But it amounts to the same thing.”

“If you will come with me to my surgery,” the Doctor suggested, with as much calmness as he could assume, “I’ll do my best for you.”

The Clockwork man bowed stiffly. “Thank you. Of course, I’m a little better than I was, but my ears still flap occasionally.”

The Doctor scarcely heard this. He had turned aside and stooped down in order to rewind the engine of his car. When he looked up again he beheld an extraordinary sight.

The Clockwork man was standing by his side, a comic expression of pity and misgiving animating his crude features. With one hand he was softly stroking the damaged bonnet of the car.

“Poor thing,” he was saying, “It must be suffering dreadfully. I am so sorry.”

Allingham paused in the turning of the handle and stared, aghast, at his companion. There was no mistaking the significance of the remark, and it had been spoken in tones of strange tenderness. Rapidly there swept across the Doctor’s mind a sensation of complete conviction. If there was any further proof required of the truth of Gregg’s conjecture, surely it was expressed in this apparently insane and yet obviously sincere solicitude on the part of the Clockwork man for an inanimate machine? He recognised in the mechanism before him a member of his own species!

The thing was at once preposterous and rational, and the Doctor almost yielded to a desire to laugh hysterically. Then, with a final jerk of the handle, he started the engine and opened the door of the car for the Clockwork man to enter. The latter, after making several absurd attempts to mount the step in the ordinary manner, stumbled and fell head foremost into the interior. The Doctor followed, and picking up the prostrate figure, placed him in a sitting posture upon the seat. He was extraordinarily light, and there was something about the feel of his body that sent a thrill of apprehension down the Doctor’s spine. He was thoroughly frightened by now, and the manner in which his companion took everything for granted only increased his alarm.

“I know one thing,” the Clockwork man remarked, as the car began to move, “I’m devilish hungry.”

That the Clockwork man was likely to prove a source of embarrassment to him in more ways than one was demonstrated to the Doctor almost as soon as they entered the house. Mrs. Masters, who was laying the supper, regarded the visitor with a slight huffiness. He obtruded upon her vision as an extra meal for which she was not prepared. And the Doctor’s manner was not reassuring. He seemed, for the time being, to lack that urbanity which usually enabled him to smooth over the awkward situations in life. It was unfortunate, perhaps, that he should have allowed Mrs. Masters to develop an attitude of distrust, but he was nervous, and that was sufficient to put the good lady on her guard.

“Lay an extra place, will you, Mrs. Masters,” the Doctor had requested as they entered the room.

“I’m afraid you’ll ’ave to make do,” was the sharp rejoinder, for there was not much on the table, and the Doctor favoured a light supper. “There’s watercress,” she added, defensively.

“Care for watercress?” enquired the Doctor, trying hard to glance casually at his guest.

The Clockwork man stared blankly at his interrogator. “Watercress,” he remarked, “is not much in my line. Something solid, if you have it, and as much as possible. I feel a trifle faint.”

He sat down rather hurriedly, on the couch, and the Doctor scanned him anxiously for symptoms. But there were none of an alarming character. He had not removed his borrowed hat and wig.

“Bring up anything you can find,” the Doctor whispered in Mrs. Masters’ ear, “my friend has had rather a long journey. Anything you can find. Surely we have things in tins.”

His further suggestions were drowned by an enormous hyaena-like yawn coming from the direction of the couch. It was followed by another, even more prodigious. The room fairly vibrated with the Clockwork man’s uncouth expression of omnivorous appetite.

“Bless us!” Mrs. Masters could not help saying. “Manners!”

“Is there anything you particularly fancy?” enquired the Doctor.

“Eggs,” announced the figure on the couch. “Large quantities of eggs — infinite eggs.”

“See what you can do in the matter of eggs!” urged the Doctor, and Mrs. Masters departed, with the light of expedition in her eye, for to feed a hungry man, even one whom she regarded with suspicion, was part of her religion.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.