The Clockwork Man (4)

By:

April 10, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fourth installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

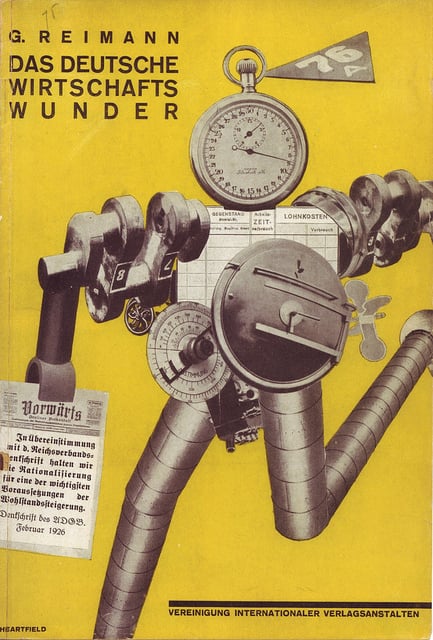

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village. Comical yet mind-blowing hijinks ensue.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R.

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man. Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s.” — Anatomy of Wonder (1995)

In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9. Newitz is also author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013) and Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (2006).

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

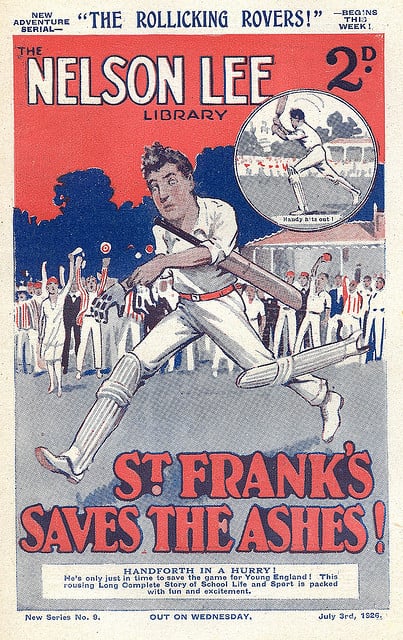

Etiquette plays an important part in the noble game of cricket. It may be bad form to refuse an obvious run; but to complain to your partner in public is still worse. Besides, Mr. Bumpus was too aghast for speech, and his stomach still pained him. He walked very slowly and with great dignity back to the pavilion, and his annoyance was no doubt amply soothed by the loud cheers that greeted his return. Gregg came out to meet him, with a rather shamefaced smile upon his features.

“I’m sorry,” he murmured, “our recruit seems to be awkward. I don’t think he quite understands.”

“He can hit,” said Mr. Bumpus, mopping his brow, “but he’s certainly an eccentric sort of individual. I called to him to run, and apparently he did not or would not hear me.”

Gregg caught hold of Arthur Withers, who was just going to bat. “Look here,” he said, “just tell our friend that he must run when he’s called.”

Arthur walked out to the wicket. His usual knee-shaking seemed less pronounced, and he felt more anxious about the Clockwork man than about himself. He paused as he drew near to him, and whispered in an ear – rather fearfully, for he dreaded a recurrence of the ear-flapping business. “The captain says will you run, please, when you are asked.”

The Clockwork man turned his head slightly to the right, and his mouth opened very wide. But he said nothing.

“You have to run,” repeated Arthur, in louder tones.

The other flapped an ear. Arthur hastened away. Nothing was worth while risking an exhibition in public such as he had witnessed in comparative seclusion. He supposed there was something about the Clockwork man really phenomenal, something that was beyond his own rather limited powers of comprehension. Perhaps cleverer people than himself might understand what was the matter with this queer being. He couldn’t.

He took his place at the wicket. The first ball was an easy one, and he managed to hit it fair on and square to mid-on. Scarcely hoping for response, he called to the Clockwork man and began to run. To his immense astonishment, the latter passed him half-way down the pitch, his legs jumping from side to side, his arms swinging round irresponsibly. It might be said that his run was merely an exaggeration of his walk. Arthur dumped his bat down quickly, and turned. As he looked up, on the return journey, he was puzzled by the fact that there was no sign of his partner. He paused and looked around him.

There had been an outburst of derisive cheering when the Clockwork man actually commenced to run, but this now swelled up into a roar of merriment. And the Arthur saw what had happened. The Clockwork man had not stopped at the opposite wicket. He had run straight on, past the wicket-keeper, past the fielders, and at the moment when Arthur spotted him he was making straight for the white sheet at the back of the ground. No wonder the crowd laughed! It was so utterly absurd; and the Clockwork man ran as though nothing could stop him, as though, indeed, he had been wound up and was without power to check his own ridiculous progress. The next moment he collided with the sheet; but even this could only prevent him from going further. His legs continued to work rapidly with the action of running, whilst his body billowed into the sagging sheet.

The spectators gave themselves up wholly to the fun. It must have seemed to them that this extraordinary cricketer was also gifted with a sense of humour, however eccentric; and that this nonsensical action was intended by way of retaliation for the ironic cheers that had greeted his running at all. Nobody, except Arthur Withers, realised that the Clockwork man had run thus far because for some reason he had been unable to stop himself. It may be remarked here that many of the Clockwork man’s subsequent performances had this same accidental air of humour; and that even his most grotesque attitude gave the observer an impression of some wild practical joke. He was so far human, in appearance and manner, in spite of those peculiar internal arrangements, which will be dealt with later, that his actions produced an instantaneous appeal to the comic instinct; and in laughing at him people forgot to take him seriously.

But Arthur Withers, still feeling a certain sense of duty towards that helpless figure battening himself against the sheet, ran up to him. He decided it would be useless to try and explain matters. The Clockwork man was obviously quite irresponsible. Arthur laid his hands on his shoulders and turned him round, much in the way that a child turns a mechanical toy after it has come to rest. Thus released, the running figure proceeded back towards the wicket, followed close at heels by Arthur, who hoped, by means of a push here and a shove there, to guide him back to the pavilion and so out of harm’s way.

But in this attempt he was unexpectedly thwarted. The Clockwork man recovered himself; he ran straight back to the wicket and then stopped dead. The umpire was in the act of replacing the bails, for the wicket had been down, and, fast as this eccentric cricketer had run in the first place, he had not been quick enough to reach the crease in time. By all the rules of the game, and beyond the shadow of doubt, he had been “run out.” He now regarded the stumps meditatively, with a finger jerked swiftly against his nose, as though recognizing a former state of consciousness. And then, with a swift movement, he took up his position in readiness to receive the ball.

This was too much for the equanimity of the spectators. Shout after shout volleyed along the lines of the hurdles. This calm deliberateness of the Clockwork man, in so reinstating himself, fairly crowned all his previous exhibitions. And the fact that he took no notice of the merriment at his expense, but simply waited for something to happen, permitted the utmost license. The crowd rocked itself in unrestrained hilarity.

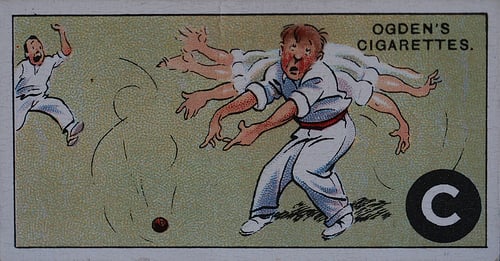

But a second later there was stony silence. For the thing that happened next was as unexpected as it was startling. Nobody, save perhaps Dr. Allingham, anticipated that the Clockwork man was capable of adding violence to eccentricity; he looked harmless enough. But apparently there lurked a dæmonic temper behind those bland, meaningless features. The thing happened in a trice; and all that followed occupied but a few catastrophic seconds. The umpire had stepped up to the Clockwork man in order to explain to him that he was expected to retire from the wicket. Not hearing any coherent reply, he emphasized his request by placing a hand suggestively on the other’s shoulder. Instantly, something blade-like flashed in the stammering air, a loud thwack broke upon the silence, and the unfortunate umpire lay prostrate. He had gone down like a log of wood.

Pandemonium ensued. The scene of quiet play was transformed into a miniature battlefield. The fielders rushed in a body at the Clockwork man, only to go down one after the other, like so many ninepins. They lay, stunned and motionless. The Clockwork man spun round like a teetotum, his bat flashing in the sun, whilst the flannelled figures flying from all parts of the field approached him, only to be sent reeling and staggering to earth. Some dodged for a moment only to be caught on the rebound. Dust flew up, and to add to the whirl and confusion the unearthly noise that had startled Arthur Withers broke out again, with terrific force, like the engine of a powerful motor suddenly started.

“I told you he was mad!” shouted Allingham, as he and Gregg leapt through the aperture of the pavilion and dashed to the rescue.

But the Clockwork man suddenly seemed panic-stricken. Just for one moment he surveyed the prostrate figures lying about on the grass like so many sacks. Then he sent the bat flying in the direction of the pavilion and rushed straight for the barrier of hurdles.

The spectators fled with one accord. Allingham and Gregg doubled up in hot pursuit. Arthur Withers, who had mustered the wit to fall down rather than to be knocked down, picked himself up quickly and joined them.

“It’s alright,” he gasped, “He – he — won’t be able to climb hurdles.”

But there was no accounting for the activities of the Clockwork man. At a distance of about a yard from the ground, his whole body took off from the ground, and he literally floated in space over the obstacle. It was not jumping; it was more like flying. He landed lightly upon his feet, without the least difficulty; and, before the onlookers could recover from their amazement, this extraordinary personage had shot like a catapult, straight up the path along which he had traveled so precariously half an hour before. In a few seconds his diminutive figure passed into the horizon, leaving a faint trail of dust and the dying echo of that appalling noise.

“My God,” exclaimed Gregg, grasping a hurdle to steady himself, “It’s it’s – incredible.”

Allingham couldn’t say a word. He stood there panting and swallowing quickly. Arthur Withers caught up to them.

“He – he – goes by machinery, sir. He’s a clockwork man.”

“Don’t be a damned fool,” the doctor burst out, “you’re talking through you’re hat.”

Gregg was listening very acutely.

“But it is so,” protested Arthur. “you didn’t see him as I did. He was like nothing on earth – and then he began to work. Just like a motor starting. And then that noise began. I’m sure there’s something inside him, something that goes wrong sometimes.”

He was still a little sorry for the Clockwork man.

“That’s my conviction,” he gasped out, too excited and breathless for further speech.

“I think,” said Gregg, with curious calmness, “I think we had better warn the police. He’s likely to be dangerous.”

The Mystery of the Clockwork Man

I

An hour and a half later Doctor Allingham and Gregg had their tea together in the sitting room of the former’s residence. Bay windows looked out upon the broad High Street, already thronged with Saturday evening excursionists. An unusually large crowd was gathered around the entrance to the “Blue Lion,” just over the way, for the news had soon spread about the town. Wild rumours passed from ear to ear as to the identity of the strange individual whose behavior had resulted in so disturbing a conclusion of the cricket match. Those among the townspeople who had actually witnessed not only this event but also the rapid flight of the Clockwork man, related their version of the affair, adding a little each time and altering their theories, so that in the end those who listened were more frightened and impressed than those who had seen.

Allingham sat in a stony silence, sipping tea at intervals and cutting pieces of cake into neat little squares, which he slipped into his mouth spasmodically. Now and again he passed a hand across his big tawny moustache and pulled it savagely. His state of tense nervous irritation was partly due to the fact that he had been obliged to wait so long for his tea; but he had also violently disagreed with Gregg in their discussion about the Clockwork man. At the present moment the young student stood by the window, watching the animated crowd outside the inn. He had finished his tea, and he had no wish to push his own theory about the mysterious circumstance to the extent of quarrelling with his friend.

After the disaster there had been much to do. Four times had Allingham’s car traveled between cricket ground and the local hospital, and it was half past six before the eleven players and the two umpires had been conveyed thither, treated for their wounds and discharged. No one was seriously injured, but in each case the abrasion on the side of the head had been severe enough to demand treatment. One or two had a long while recovering full consciousness, and all were in a condition of mental confusion and gave wildly incoherent reports of the incident.

There had been times, during those journeys to and fro, when Gregg found it difficult to save himself from outbursts of laughter. He had to bite his lip hard in the effort to hold in check an imagination that was apt to run to extremes. From one point of view it had certainly been absurd that this awkward being, with his apparently limited range of movement, should have managed in a few seconds to lay out so many healthy, active men. By comparison, his battling performance, singular as it had seemed, faded into insignificance. The breathless swiftness of the action, the unerring aim, the immense force behind each blow, the incredible audacity of the act, almost persuaded Gregg that the thing was too exquisitely comic to be true. But when he forced himself to look at the matter seriously, he felt that there were little grounds for the explanation that the Clockwork man was simply a dangerous lunatic. The flight at preposterous speed, the flying leap over the hurdle, the subsequent acceleration of his run to a pace altogether beyond human possibility, convinced the young undergraduate, who was level-headed enough, although impressionable, that some other explanation would have to be found for the extraordinary occurrence.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.