The Clockwork Man (6)

By:

April 24, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the sixth installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

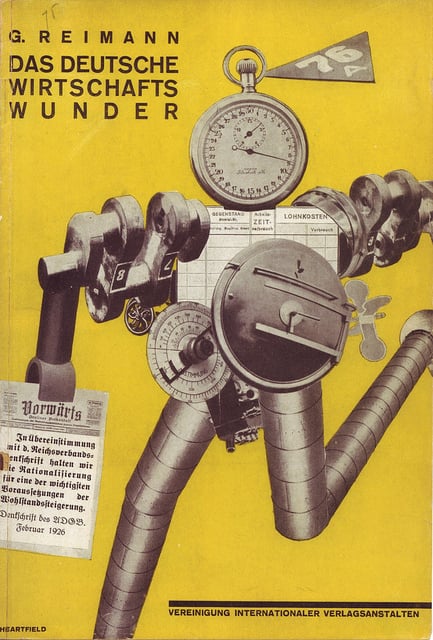

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village. Comical yet mind-blowing hijinks ensue.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R.

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man. Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s.” — Anatomy of Wonder (1995)

In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9. Newitz is also author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013) and Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (2006).

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

“I regard that statement of his as highly significant,” resumed Gregg, after a slight pause. “For, of course, if the Clockwork man really is, as suggested, a semi-mechanical being, then he could only have come from the future. So far as I am aware, the present has not yet evolved sufficiently even to consider seriously the possibility of introducing mechanical reinforcements into the human body, although there has been tentative speculation on the subject. We are thousands of years away from such a proposition; on the other hand, there is no reason why it should not have already happened outside of our limited knowledge of futurity. It has often occurred to me that the drift of scientific progress is slowly but surely leading us in the direction of some such solution of physiological difficulties. The human organism shows signs of breaking down under the strain of an increasingly complex civilisation. There may be a limit to our power of adaptability, and in that case humanity will have to decide whether it will alter its present mode of living or find instead some means of supplementing the normal functions of the body. Perhaps that has, as I suggest, already happened; it depends entirely upon which road humanity has taken. If the mechanical side of civilization has developed at its present rate, I see no reason why the man of the future should not have found means to ensure his efficiency by mechanical means applied to natural functions.”

Gregg sat up in his chair and became more serious. Allingham fidgeted without actually interrupting.

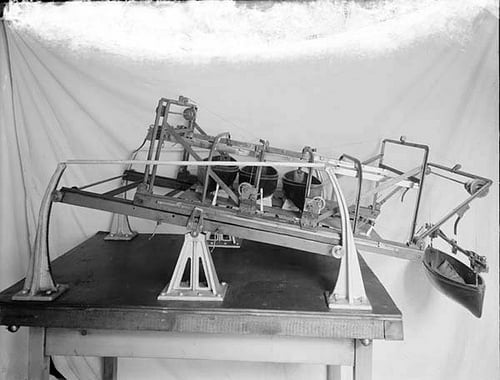

“Imagine an exceedingly complex kind of mechanism,” Gregg resumed, “an exaggeration of the many intricate types of modern machine in use to-day. It would have to be something of a very delicate description, and yet rather crude at first in its effect. One thinks of something that would work accurately if in rather a limited sort of way. You see, they would have to ensure success in some things at first even at the sacrifice of a certain general awkwardness. It would be a question of taking one thing at a time. Thus, when the Clockwork man came to play cricket, all he could do was to hit the ball. We have to admit that he did that efficiently enough, however futile were the rest of his actions.”

“Hot air,” interrupted Allingham, reaching for his tobacco pouch, “that’s all this is.”

“Oh, I won’t admit that,” rejoined Gregg, cheerfully, “we must acknowledge that what we saw this afternoon was entirely abnormal. Even when we were talking to him I had a strong feeling come over me that our interrogator was not a normal human being. I don’t mean simply his behavior. His clothes were an odd sort of colour and shape. And did you notice his boots? Curious, dull-looking things. As though they were made out of some kind of metal. And then, the hat and wig?”

“You’re simply imagining all these things,” said Allingham, hotly, as he rammed tobacco into his pipe.

“I’m not. I really noticed them. Of course, I didn’t attach much importance to them at the time, but afterwards, when Arthur Withers was telling his story, all that queer feeling about the strange figure came back to me. It took possession of me. After all, suppose he is a clockwork man?”

“But what is a clockwork man?” demanded Allingham.

“Well, of course I can’t explain that exactly, but the term so obviously explains itself. Damn it, he is a clockwork man. He walk, he talks, and behaves exactly as one would imagine — ”

“Imagine!” burst out Allingham. “Yes, you can imagine such a thing. But you are trying to prove to me that this creature is something that doesn’t and can’t exist outside your imagination. It won’t wash.”

“But you agree,” said Gregg, unperturbed, “that it might be possible in the future?”

“Oh, well, everything is possible, if you look at it in that light,” grudgingly admitted the other.

“Then all we have to do is to prove that the future is involved. Our lunatic must convince us that he is not of our age, that he has, in fact and probably by mechanical means, found his way back to an age of flesh and blood. So far, we are agreed, for I willingly side with you in your opinion that the Clockwork man could not exist in the present; while I am open to be convinced that he is a quite credible invention of the remote future.”

He broke off, for at that moment a car drew up in front of the window, and the burly form of Inspector Grey stepped down in company with two constables and a lad of about fifteen, whom both Gregg and the doctor recognised as an inhabitant of the neighbouring village of Bapchurch.

“Well?” said Allingham, as the party stamped awkwardly into the room, after a preliminary shuffling upon the mat. “What luck?”

“Not much, doctor,” announced the inspector, removing his hat and disclosing a fringe of carroty hair. “We ain’t found your man, and so far as I can judge we ain’t likely to. But we’ve found these.”

He laid the Clockwork man’s hat and wig on the table. Gregg instantly picked them up and began examining them with great curiosity.

“And young Tom Driver here, he’s seen the man himself,” resumed the inspector.

“That’s ’ow we come by the ’at and wig. Tell the gentlemen what you saw, Tom.”

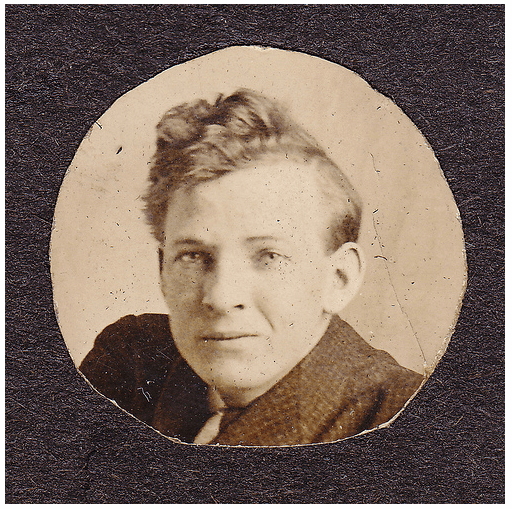

Tom Driver was a backward youth at the best of times, but he seemed quite overcome by the amount of responsibility now thrust upon him. He shuffled forward, pressing his knees together and holding a tattered cap between his very dirty fingers. A great shock of curly yellow hair fell almost over his large brown eyes, and his face was long and pinched.

“I see the man,” he began, timidly, “I see ’im as I was going along the path to Bapchurch.”

“Was he going very fast?” said Gregg.

“No, sir, he weren’t walking at all. He’d fallen into the chalk pit just by Rock’s Bottom.”

Allingham burst out into a great roar of laughter; but Gregg merely smiled and listened.

“That’s ’ow I come to see ’im,” said Tom, shifting his cap about uneasily. “I was in a bit of a ’urry ’cos mother said I wasn’t to be late for tea, and I’d been into the town to buy butter as we was a bit short. As I come by Rock’s bottom — and you know ’ow the path bends a bit sharp to the left where the chaulk pit lies — it’s a bit awkward for anyone ’as don’t know the path — ”

“Yes, go on,” said Gregg impatiently.

“Well, as I was coming along I see something moving about just at the top of the pit. At first I thought it was a dog, but when I come nearer I could see it was a pair of legs, kicking. Only they was going so fast you couldn’t hardly tell one from t’other. Well, I ran up, thinking ’as very likely someone ’ad fallen in, and sure enough it was someone. I caught ’old of the legs, and just as I was about to pull ’im out — ”

“Did the legs go on kicking?” said Gregg, quickly.

“Yes, sir, I ’ad a job to ’old them. And then, just as I was going to pull ’im out, I noticed something — ”

Tom paused for a moment and began to tremble. His teeth chattered violently and he looked appealingly at his listeners as though afraid to continue.

“Go on, Tom,” commanded Inspector Grey. “spit it out, lad. It’s got to be said.”

“He — he — hadn’t got no back to his head,” blurted out Tom at last.

“What!” rapped out Allingham.

“There you are,” said Tom, cowering and glancing reproachfully at the inspector,” I told you as ’ow t’ gentlemen wouldn’t believe it as ’and’t seen it for themselves.”

“But what did you see?” enquired Gregg, kindly. “What was there to be seen?”

Tom’s eyes searched the room as though looking for something. Gregg was standing with his back to the fireplace, but noticing that Tom seemed to be trying to look behind him, he moved away. Tom immediately pointed to the clock that stood on the mantelpiece.

“It was a clock,” he said slowly, “just like that one, only more so, in a manner of speaking. I mean it ’ad more ’ands and figures, and they was going round very fast. But it ’ad a glass face just like that one, and it was stuck on ’is ’ead just where the back ought to be. The sun was shining on it at first. That’s why I couldn’t be sure what it was for a long time. But when I looked closer, I could see plain enough, and it made me feel all wobbly, sir.”

“Was there a loud noise?” asked Gregg.

“No sir, not then. But the ’ands was moving very fast, and there was a sort of ’umming going on like a lot of clocks all going at once, only quiet like. I was so taken back I didn’t know what to do, but presently I caught ’old of ’is legs and tried to pull ’im out. It weren’t a easy job, ’cos ’is legs was kicking all the time, and although I ’ollered out to ’im ’e took no notice. At last I dragged ’im out, and ’e lay on the grass, still kicking. “’E never even tried to get up, and at last I took ’old of his shoulders and picked ’im up. And then as soon as I stood ’im on his feet, and afore I ’ad time to ’ave a good look at ’im, off he goes, like greased lightning. An awful noise started, like machinery, and afore I ’ad time to turn round ’e was down the path towards Bapchurch and out of sight. I tell you, sir, it gave me a proper turn.”

“But how did you come by these?” questioned Gregg, who was still holding the hat and wig.

“I see them lying in the pit,” explained Tom, “they must’ve dropped off ’is ’ead as he lay there. Of course, ’e ’adn’t fallen very far, otherwise ’is legs wouldn’t ’ave been sticking up. It ain’t very steep just there, and ’is ’ead must ’ave caught in a bit of furze. But the ’at and wig ’ad rolled down to the bottom. After ’e’d gone I climbed down and picked them up.”

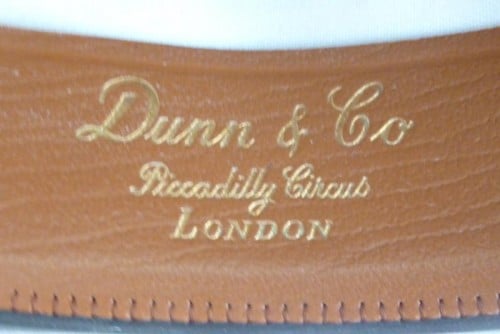

Gregg passed the hat and wig to Allingham, and whispered something. The other looked at the inside of the hat. There was a small label in the center, with the following matter printed upon it : —

UNIVERSAL HAT PROVIDERS.

ESTABLISHED OVER 2,000 YEARS.

For a moment Allingham’s face was a study in bewilderment. He tried to speak, but only succeeded in producing an absurd snigger. Then he tried to laugh outright, and was forced into rapid speech. “Well, what did I say? The whole thing is preposterous. I’m afraid, inspector, we’ve troubled you for nothing. The fact is, somebody has been guilty of a monstrous hoax.”

“Look at the wig, look at the wig,” interrupted Gregg, feverishly.

Allingham did so. Just on the edge of the lining there was an oblong-shaped tab, with small gold lettering :—

“Well, well, it’s what I said,” the doctor went on, swallowing quickly, “someone has — someone has —”

He broke off abruptly. Gregg was standing with his hands behind him. He shook his head gravely.

“It’s no use, doc,” he observed, quietly, “we’ve got to face it.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.