Phone Horror (9)

By:

July 10, 2014

[Ninth in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 were adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005-06; parts 5-10 appear here for the first time.]

The Leaky Telephone: Asian Water Horror

Perhaps a freak of the wind — yet perhaps a sign of remembrance, This fall of a single leaf on the water I pour for the dead.

— “Fancies of Another Faith,” collected by Lafcadio Hearn, In Ghostly Japan (1899)

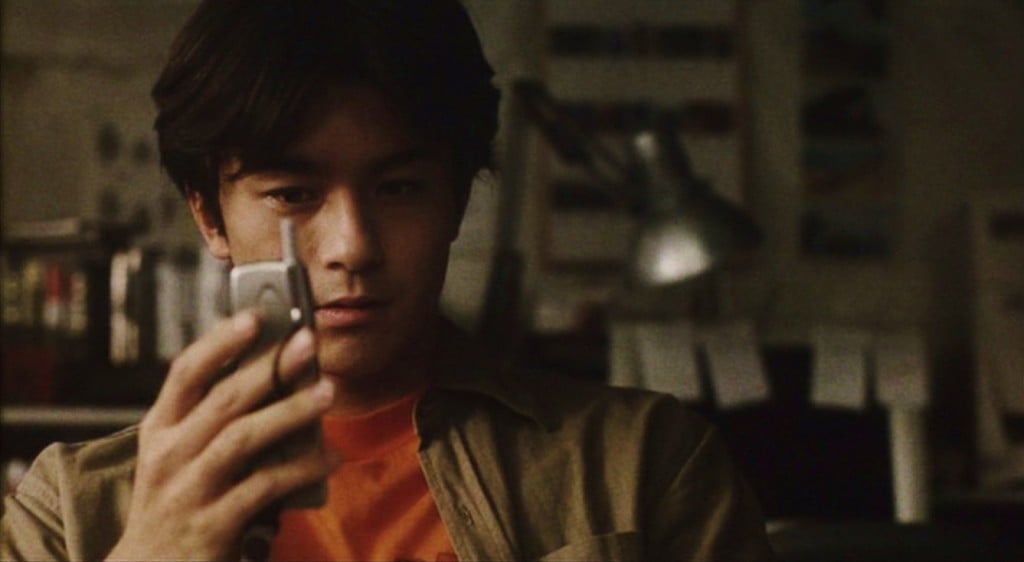

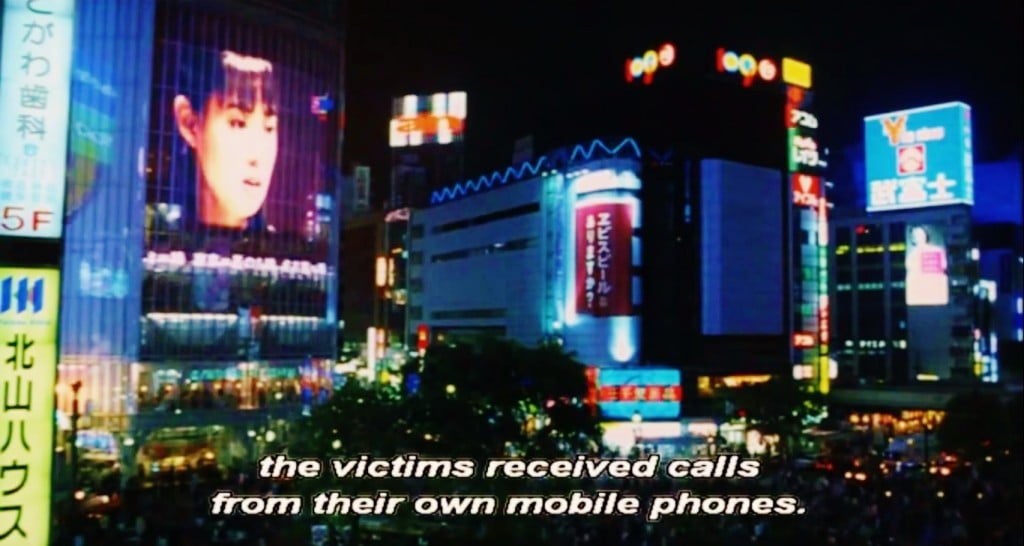

Asian horror surfaced here in the late 1990s, a green, dripping corpse. From Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Taiwan came ghoul children with black hair and chalky faces, crawling and twitching or standing stone still, taking revenge on goggle-eyed humans in elevators and hallways. Aside from the iconic contours of the ghosts themselves, technology was the principal novelty of this new wave. No kitchen knives, no hockey masks: the Far East delivered digital prophecy via videocassette (Ringu, Rasen), Internet (Pulse), camera (Shutter) — and of course the telephone (Phone, One Missed Call 1, 2, and 3).

In the manner of the Italian western, Bombay musical, or Nordic noir, Asian horror used quirks of cultural exchange to reanimate an exhausted form. Like many Westerners, I discovered it not “pure” but mediated — by way of The Ring (2002), the US remake of Japan’s Ringu (1998). Breaking form, Hollywood didn’t just rewrite the original, it improved on it. The Ring had the matchless Naomi Watts speeding hither and yon, recovering chunks of back-story from cluttered archives and cobwebby basements; and was unexpectedly dread- rather than shock-centered, rich with silence and evocatively irrational imagery. Quite an experience to see that deadly video for the very first time.

The Ring also brought to the surface of (a Westerner’s) consciousness what may be the basic thematic equation of Asian horror: technology, the body, and water. A moment of absolute focus occurs. Watts sips from a glass of water, begins to choke, and pulls from her throat a wire connected to a brainwave sensor. She then picks up her telephone receiver to find water leaking from its earholes — message and augury from a ghost child’s wet grave. Water goes into the body, and technology comes out; from technology seeps water, the (in)substance that covers the earth and constitutes most of what we call the body. All is oneness and flow.

Awash in flash and gadgetry, Asian horror is equally saturated with the most basic of earthly elements. As it might well be: Japan is a nation of islands, while the Koreas are on a peninsula, and the Pacific Rim is named for an ocean. Flood, typhoon, and tsunami have been a reality of the Rim since before recorded time. The most recent natural water disaster, the Japanese tsunami of 2011, killed nearly 16,000 people, and left another 2,600 missing. Just yesterday — June 9, 2014 — Tropical Storm Neoguri made landfall in Japan.

Let more water seep through that telephone. In Buddhism, water, or mizu, represents all that flows, that is fluid and formless, and it’s considered vital to keep the dead supplied with fresh water. The late-nineteenth-century Japanophile Lafcadio Hearn wrote of cemeteries outfitted with wells for this purpose: visiting relatives would bring water to pour into the cisterns, or mizutamt, that irrigated the ground occupied by their loved ones. But in an old cemetery, with thousands of mizutamt, the water would eventually stagnate and breed bloodthirsty mosquitoes:

… they rise by millions from the water of the dead; and, according to Buddhist doctrine, some of them may be reincarnations of those very dead … Anyhow the malevolence of the [mosquito] would justify the suspicion that some wicked human soul had been compressed into that wailing speck of a body….

Those dripping telephone holes are the very “slits” that Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss suggested might admit the magical and mystical into “mundane life.” They are also the breaks in circuitry whereby the ghosts of folk tradition can permeate and impregnate even the trendy fixations of the modern, techno-hungry Asian age. In folk tales and ghost stories of the Far East, spirits often haunt rivers and lakes, and if the angry, destructive ghosts of Asian horror evoke the onryo, the vengeful spirit of Japanese tradition, they are also related to the kappa, or water-goblin.

Water runs through Phone (South Korea, 2002). In every other scene, it is raining; at the end, the phone carrying an accursed number is dropped into the ocean — and goes on ringing. (The production company is even called Toilet Pictures!) A rainstorm likewise drenches the opening of One Missed Call 2 (Japan, 2005), inspiring a little girl to tell her teacher that “When it rains, the souls of the dead pour down to Earth.” Faucets leak, and a victim dies a horrible limb-twisting death beneath an exploding showerhead. A girl answers a phone, gets the death call, and is next seen lifeless in a shallow creekbed. Characters somehow think that, by throwing their phones in water, they will drown the curse rather than nourish it — give fresh water to the dead.

The first sound heard in Pulse (Japan, 2001), one of the few Asian horror films to transcend the genre (it bears comparison with David Lynch), is the nostalgic irritant of a mid-1990s Internet logon — whine, click, buzz. But this is overwhelmed by the sound of ocean waves, upon which the story begins and ends. In between the opening and closing waves come sporadic ghostly communications via phone: a voice calls a character and says “Help” over and over, in a loop-like monotone; simultaneously, the image of a dead friend’s room appears on the phone.

This expanding mesh of metaphor — body, technology, brainwaves and radio waves and ocean waves, water as conductant of spirit, energy, evil — soon enough melts together, flows into a common cistern of amoebic life and potential reincarnation. This distinguishes Asian horror, since a clear difference between Eastern and Western perspectives is the former’s indivisibility of form and essence, of substance and soul. “Ghosts and people are the same,” says a character in Pulse, “whether they’re dead or alive”; and while the movie does not quite want to believe her, it cannot prove her wrong.

This sounds a theme of oneness, of life and death as separate currents in a single river, which in the One Missed Call series extends from the physical plane to time itself: past, present, and future collapse as people answer their phones to hear the sound of their own deaths, and a curse from the past becomes the defining fact of everyone’s present. In the first of the series, each of the ghost’s successive victims is accessed through the memory of the last victim’s phone — digital memory acting, like its human model, as another “slit,” another leaky telephone hole admitting the (in)substance of the past. (The young heroine of One Missed Call has a phobia — sensible, it turns out — about looking into holes.)

Making a coherent cultural-historical understanding of these propositions, presumptions, and attempted connections would require the erudition of the Asianist I am not. But I do believe that the folk tradition of any country flows into and out of itself, precisely like water; that cultural legendries are as vast and deep as oceans; that some of what forms Asian horror is an apprehension of oneness between living and dead, natural and supernatural; and that the equation of water, bodies, and technologies therein bespeaks nothing more or less than the often horrific inescapability of the past, even as we strain to stay above the rising tides of our own miraculous and disastrous moment in time.

… and they were startled to see, by the light of a small lamp which had been kindled before a shrine in that room, the figure of the dead mother. She appeared as if standing in front of a tansu, or chest of drawers, that still contained her ornaments and her wearing-apparel. Her head and shoulders could be very distinctly seen; but from the waist downwards the figure thinned into invisibility; it was like an imperfect reflection of her, and transparent as a shadow on water.

— Lafcadio Hearn, Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903)

***

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |