BESTIARY (12A)

By:

August 25, 2021

One in a series of posts — curated by Matthew Battles — the ultimate goal of which is a high-lowbrow bestiary. This particular installment is in three parts.

All installments: 1904–1933: Busy as a beaver | 1934–1963: Eager beaver | 1964–2003: Beaver patrol

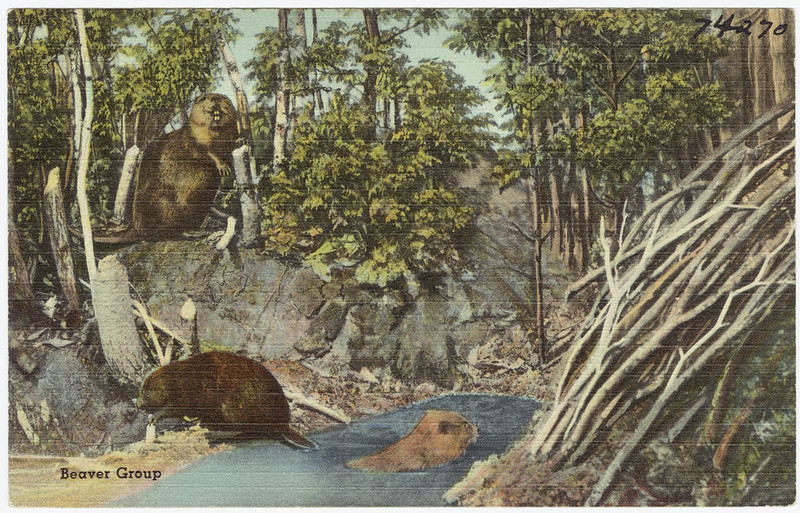

The beaver is a large — though not as large as its laid-back cousin, the capybara — and semiaquatic rodent native to the temperate northern hemisphere.

Because it tirelessly topples and chisels apart trees, with which material it constructs dams (for preserving its water) and lodges (for its habitation), the beaver has become an emblem of industriousness and eagerness. As I’m interested in ideologies of work and labor, I thought I’d take a look — quickly, haphazardly even — at how the beaver’s use as a symbolic representation in US pop culture evolved over the course of the 20th century. The “thin description” resulting from my preliminary research and analysis is what you’ll find distributed over the three BEAVER installments.

Before we get to 1904–1933 beaver depictions, here’s a word or two about the beaver itself.

The beaver’s skull, with its unusually deep and wide cheek bones, evolved in order to withstand the forces generated by its powerful chewing muscles.[1] The orange hue of the beaver’s chisel-shaped incisors, which grow continuously, reveals the presence of iron compounds; although their tooth enamel is structurally the same as ours, chemically its as though their choppers have been injected with iron.

The beaver’s other parts are also impressive. It can grasp and manipulate objects with its front feet. Its valved nostrils and ears close underwater, while nictating membranes cover its eyes. Because of the placement of its teeth, and because its epiglottis and tongue protect against water that might flow into the larynx and trachea, the beaver can chew wood even while submerged. And its weird tail — partly muscular and hairy, partly flat and scaly — acts as a support when the beaver is chewing down a tree, and as a rudder when it is swimming.

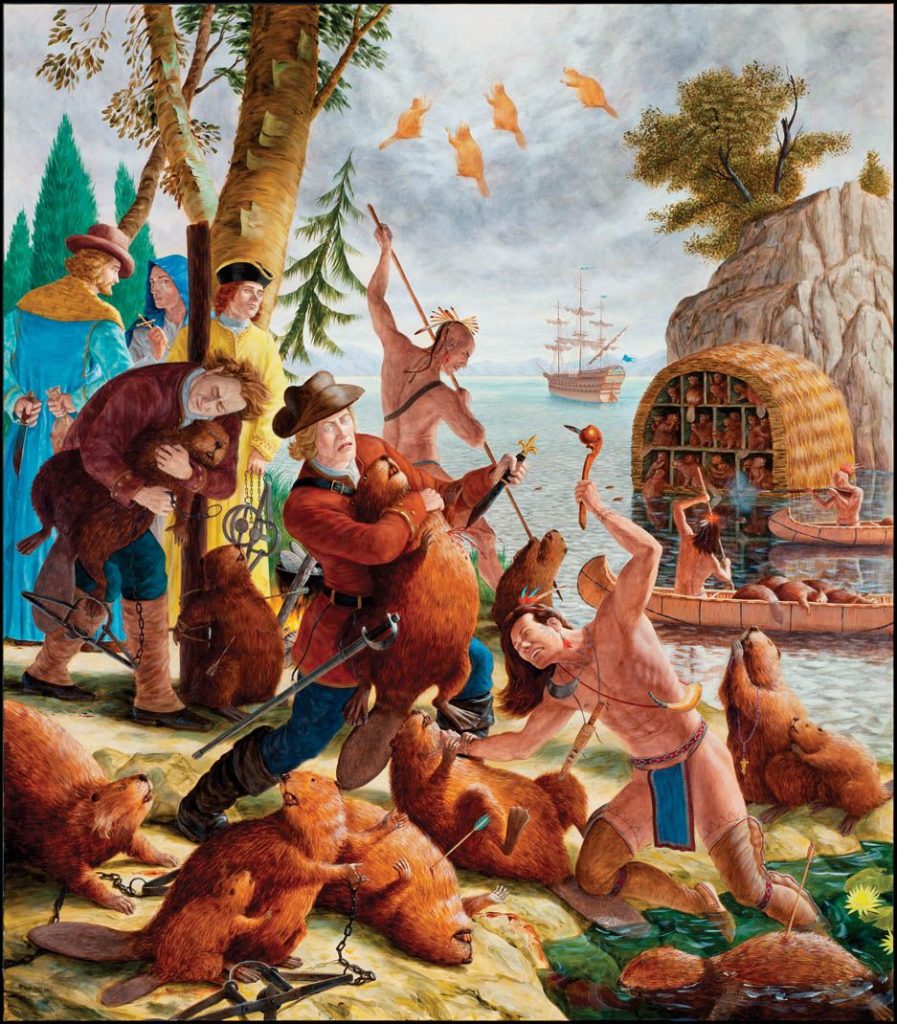

The beaver is a “keystone” species on which other species in its ecosystem depend. The infrastructure it builds — bracing log poles against the banks of a body of water, aligning them in the direction of the water’s flow, weighing them down with rocks, and filling in gaps with grasses — creates crucial wetlands. Yet humankind has been cruel to this important creature. For centuries we hunted the beaver for its fur, its meat, even its castoreum — an exudate, found in its castor sacs (or “beaver-stones”), much prized at one time for use in medicine, perfume, and flavoring[2]. (And apparently still prized today.)

Once widely distributed across North America, beavers were much reduced during Euro-American settlement of the continent.

It has been argued that beaver fur, used to make felt for hats in Europe, was the major impetus for exploration of the New World which resulted in European colonization. Beaver hats were fashionable across much of Europe from 1550–1850. Between 1860 and 1870, which is to say as this fashion was finally ending, the Hudson’s Bay Company and fur companies in the US still purchased over 150,000 beaver pelts per year. Consequently, by the early 20th century beavers were extirpated through human trapping and hunting from vast regions of North America.

By the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, beaver hats were largely replaced by silk hats. Today, thanks to protections put in place at almost the last minute, the beaver is no longer endangered. Protections have allowed the beaver population on the continent to rebound to an estimated 6–12 million by the late 20th century. Impressive — but this is a fraction of the originally estimated 60–400 million North American beavers before the days of the fur trade.

I didn’t set out to research pre-20th century beaver pop culture representations, but in the course of my efforts I turned up a few 19th-century factoids. So… a few more preliminary notes.

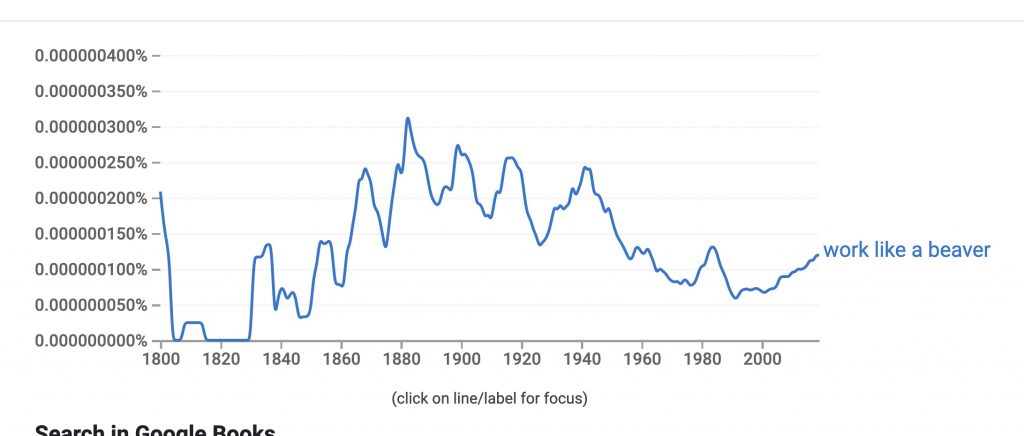

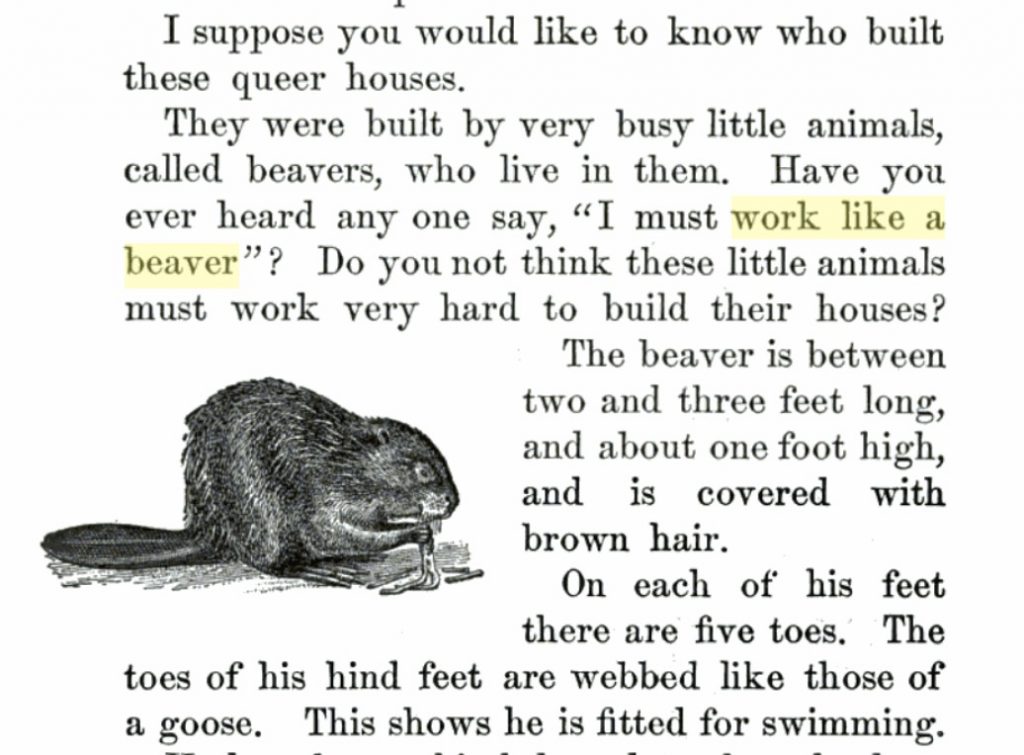

The phrase “to work like a beaver” is a semi-admiring, semi-pejorative American phrase first attested in the 1740s. It has been suggested, for example in Toward a Social History of American English, that the phrase was coined by mountain men or backwoodsmen during that period. It rapidly evolved from jargon to a proverb. An 1889 dictionary of Americanisms glosses “to work like a beaver” as “obviously a simile denoting industry and perseverance.” The phrase was in common use by the early 20th century. We read, for example, in the January 1900 edition of the journal School Education, “I think you must know by this time what it means to ‘work like a beaver.'”

In fact, according to a Google Books Ngram search, the phrase “work like a beaver” spiked in popularity after the mid-19th century — and wouldn’t decline sharply until after WWII. When we get to the sections of this post on the Forties and Fifties, we’ll look into this matter.

Thomas Carlyle worried that, c. 1850, his fellow countrymen were becoming “beaverish” — that is to say, merely instinctive, working away at immediate goals without thinking of the big picture, devolving inexorably into a state of mere “beaverism.”

My hasty research suggests that the beaver’s positive and negative connotations would remain in tension through the 20th century… except in children’s literature and educational materials, where working like a beaver is always depicted as a habit worth emulating.

1902 letterhead for Canfield Supply Company — Kingston, NY.

OK, let’s get to the first of three installments in this series.

During the first three decades of the 20th century, we find the beaver’s industriousness held up as an inspiration for children and adults who might be tempted to live a “bank beaver” style of life…

Note that in 1909, the manufacturing manager Frederick Winslow Taylor would publish The Principles of Scientific Management. Here, Taylor argued that by optimizing and simplifying jobs, productivity would increase. “In the past man has been first,” he proclaimed in the book’s Introduction. “In the future the system must be first.”

A 1904 booklet about beavers that’s actually an advertising vehicle for Dr. Jones’ Beaver Oil — as a curative for sciatica, rheumatism, neuralgia, sore throat, bronchitis, back ache, toothache, headache, bruises, sprains, lameness, chilblains, frostbite, etc. The author of the booklet, Dr. M. Spiegel, was charged in 1915 with violation of the Food & Drugs Act for misbranding and exaggerated claims for the efficacy of Dr. Jones’ Beaver Oil.

SHAGGYCOAT: Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver is a 1906 book by Clarence Hawkes, a naturalist and prolific Massachusetts author known as the “blind poet of Hadley.” It’s interesting to find Hawkes commenting on the phrase “busy as a beaver” here:

The phrase “as busy as a beaver” was anything but descriptive of their life now, for they did little but sleep and eat bark. They had provided well for these cold months, and now they had nothing to do but enjoy themselves. I am inclined to think that the maxim about working like a beaver only applies to two or three months in the autumn, for the rest of the year the beaver is a very lazy fellow.

Sounds as though Hawkes is a dissenting voice in the twentieth century’s moralistic busy-beaver discourse… but, later in the story Shaggycoat turns against a “bank beaver” (i.e., one living in a burrow apart from the colony) who doesn’t want to help build a dam: “Shaggycoat did not like this lazy manner of living, besides he did not think it safe. When day after day Brownie refused to help on the dam, he flew into a rage with so lazy a fellow, and gave Brownie such a severe trouncing that he never dared show himself about the lake afterward.”

I should also note the similarity between this book and Watership Down, both of which began with men destroying a creature’s habitat… and end with the establishment of a utopian new colony.

Because my (cursory) search for pre-20th century kiddie books promoting the beaver as a symbol of industriousness didn’t turn anything up… for the moment, I’m going to hypothesize that this publishing phenomenon begins with Shaggycoat. But there’s always an earlier example… help me out, readers!

A 1913 adventure for Scouts. By c. 1969, “beaver patrol” would take on a bawdy meaning in US pop culture.

The 1913 book In Beaver World, by Enos Abijah Mills, also extols the beaver’s work ethic:

To “work like a beaver” is an almost universal expression for energetic and intelligent persistence, but who realizes the magnitude of the beaver’s works? What he has accomplished is not only monumental but useful to man. He was the original Conservationist.

This admixture of hard work and conservationism is one that we will see again.

PS: The moving assembly line was developed for the Ford Model T and began operation on October 7, 1913, at the Highland Park Ford Plant, and continued to evolve after that. It will be interesting to see whether depictions of the beaver evolve from this point forwrd — i.e., from skilled craftsman to assembly-line laborer.

“TIM”: In 1914, MIT — a technology school that didn’t, yet, have a mascot — selected the beaver to fulfill that role. “The beaver was chosen as the mascot of Technology,” we read, “because of its remarkable engineering and mechanical skill and its habits of industry.” No one called the mascot “Tim” (“MIT” in reverse) until the ’90s. Before then, it was called Bucky, Chipper, and Eager.

BROWNIE BEAVER: The Tale of Brownie Beaver is a c. 1916 children’s book by the prolific American author Arthur Scott Bailey, one of many installments in a series that includes The Tale of Timothy Turtle (c. 1919), The Tale of Master Meadow Mouse (c. 1921), etc.

Barring further intel, I’m going to name Brownie Beaver the progenitor of the long-running meme in which a beaver whose first name begins with a “B” is held up as an example, for impressionable children, of how hardworking they should strive to be too.

Well, Brownie Beaver used to get just as hungry as any little boy or girl. How he did tear at the bark, when he finally began to eat! And how full he stuffed his mouth! And how he did enjoy his meal! But everybody will admit that he had a right to enjoy his dinner, for he certainly worked hard enough to get it.

Note that Brownie (the name of the good-for-nothing “bank beaver” in 1906’s Shaggycoat) encounters “a lazy fellow called Tired Tim who laughed openly at Brownie.” I’m beginning to empathize with the bank beavers, myself.

PADDY BEAVER: The Adventures of Paddy Beaver is a 1917 children’s book by the Massachusetts-based author Thornton Waldo Burgess. (In 1914, the prolific Burgess published Jack Frost Helps Paddy the Beaver, but this sequel became more famous.) Paddy’s theme song is: “Work, work all the night / While the stars are shining bright; / Work, work all the day; / I have got no time to play.” You get the idea; this is propaganda aimed at children. “Now [Paddy] was ready to go to work, and when Paddy begins work, he sticks to it until it is finished. He says that is the only way to succeed, and you know and I know that he is right. … And as he worked, Paddy was happy, for one can never be truly happy who does no work.”

Burgess has the following to say about Paddy’s usage of natural resources: “Now Paddy the Beaver loves the Green Forest as dearly as you and I do, and perhaps even a little more dearly. You see, it is his home. Besides, Paddy never is wasteful. So he cuts down a tree so that he can get all the bark instead of killing a whole lot of trees for a very little bark, as he might do if he were lazy. There isn’t a lazy bone in him — not one.” Following in the footsteps of Enos Abijah Mills, Burgess economically conflates a moral lesson about the necessity of conservation with one about the value of hard work.

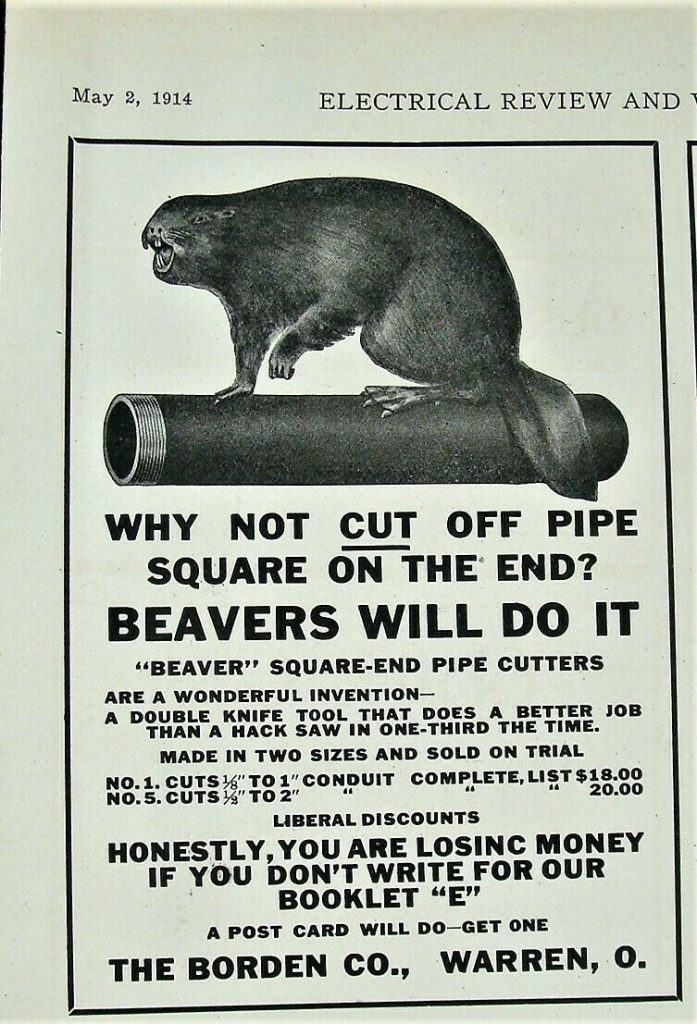

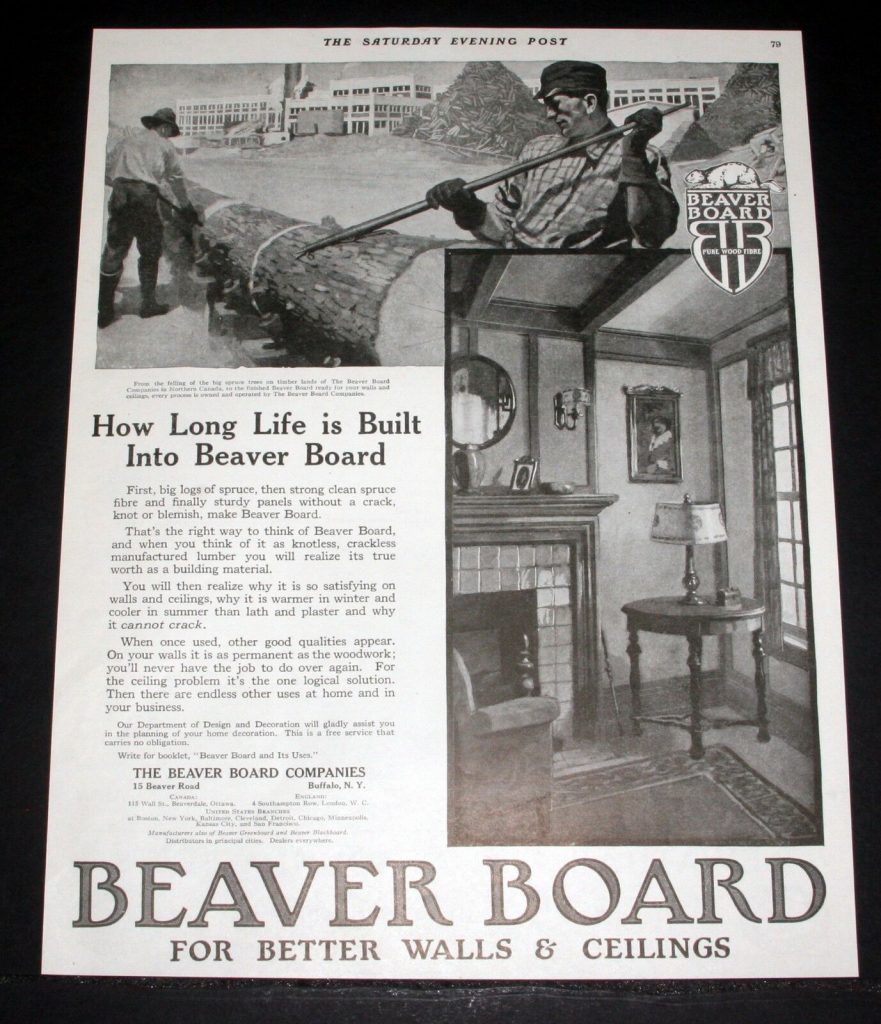

A few ads from this period:

Beaverboard is a building material formed of wood fibre compressed into sheets. It was originally a trademark: The Beaver Board Company was founded in Beaver Falls, New York and began producing fiberboard in 1907.

Agricultural colleges have long published extension bulletins aimed at a professional practitioner readership. In a 1915 bulletin from The University of Delaware School of Agriculture, we find a survey or personality test with the following bullet points: “Can you take responsibility? * I like to take charge of things and see them through. * I’ll take over if I have to, but I’d rather let someone else be responsible. * There’s always some eager beaver around wanting to show how smart he or she is.” According to the OED, the phrase “eager beaver” dates to c. 1942… but my research suggests it’s a somewhat earlier colloquialism or slang term.

Already by 1915, it seems, “eager beaver” is the sort of aggravated comment that one of humankind’s bank beavers might utter when forced to interact with a Shaggycoat type.

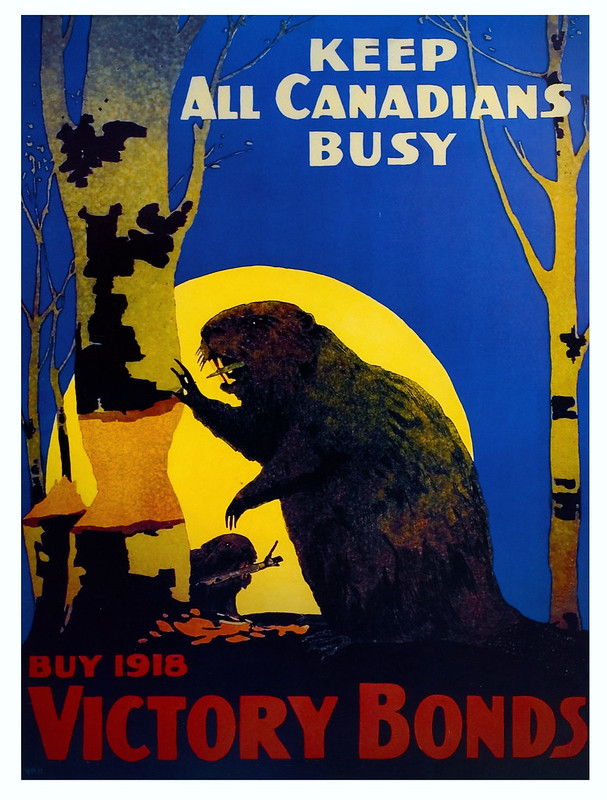

By 1918, as the poster above indicates, we find the beaver deployed not only as an emblem of industriousness, but as an emblem of Canada itself. This latter use of the beaver has a fascinating history of its own, which I have relegated to a footnote.[3]

I have not read either of the children’s story books shown here. Toto the Bustling Beaver is from 1920. Ellen D. Wangner’s The Busy Beavers of Round Top is from 1921. But one gets the strong impression that they are about the value of industriousness.

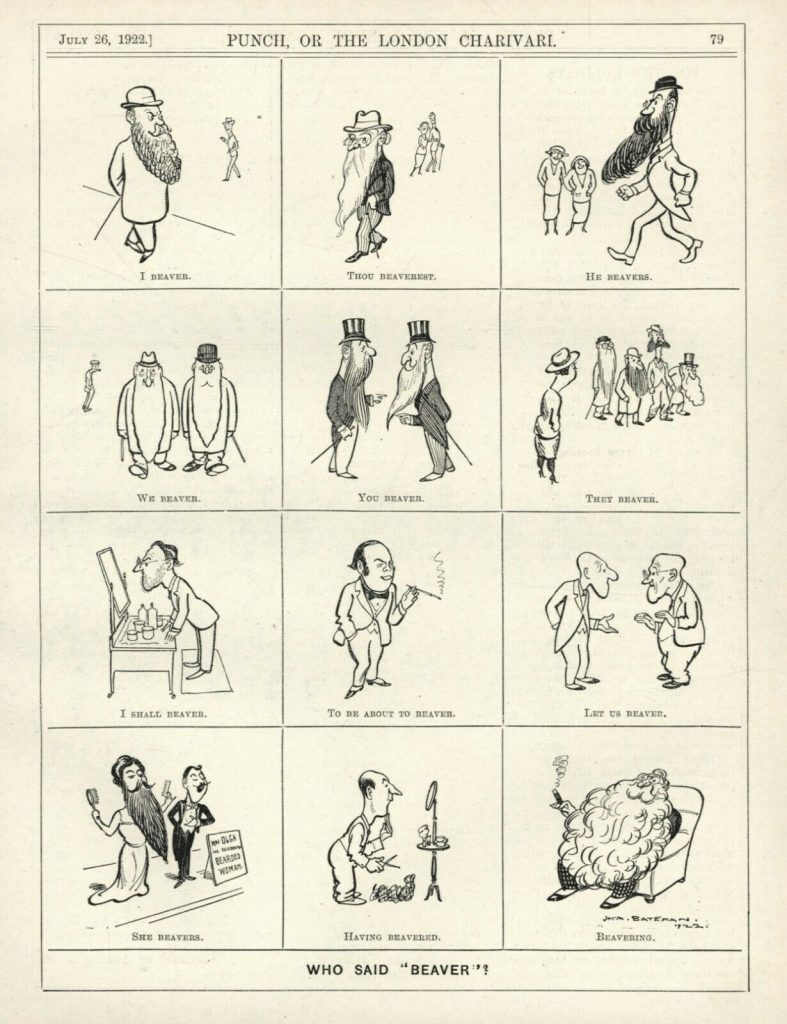

Here’s a 1922 British cartoon which references a fad game of the time called “Beaver,” in which points were scored for sighting bearded men. (The slang use of “beaver” to mean “beard” dates at least to the 1870s.) If I understand this etymological site’s discussion correctly, this game may be the source of the association of “beaver” with the pudenda.

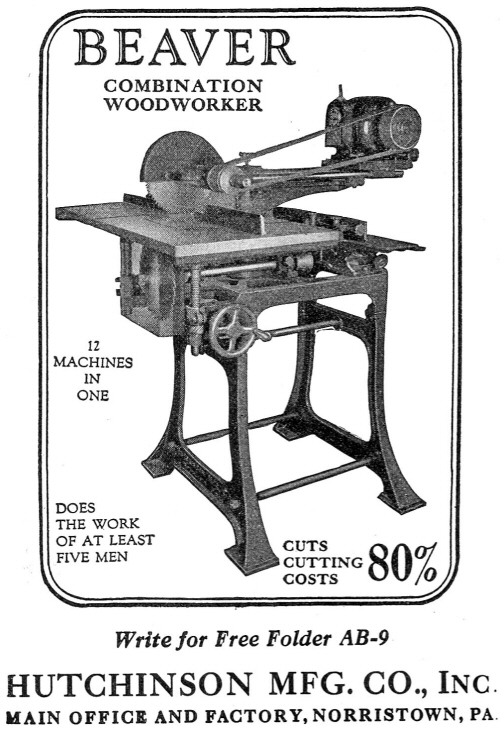

Here are a couple of US ads from the latter part of the Teens.

During the Twenties, the assembly line technique perfected by Ford spread rapidly. Companies had to have assembly lines, or risk going broke by not being able to compete. However, the repetition of doing the same specialized task all day long could lead to boredom or even alienation. In this socio-economic context, it’s fascinating to see beavers, during the Twenties, depicted in cartoons as unbored, unalienated assembly-line laborers.

At the apex of the Twenties — in the autumn of 1929 — there was a major American stock market crash. The Great Depression spread from America to the rest of the world; between 1929 and 1932, worldwide GDP fell by an estimated 15%. The US didn’t fully recover until 1939. Capitalism underwent a metamorphosis, during this period; as Baudrillard puts it, “Consumption became a strategic element, the people were mobilized henceforth as consumers, their ‘needs’ became as essential as their labor power.” It will be interesting to watch — see the next installment in this series — for some sort of parallel shift in depictions of the beaver after 1929.

BOBBY BEAVER: Like Paddy Beaver, Bobby Beaver — a character in The Child Library Readers, Book One (1924) — is so diligent that he cannot even carry on a conversation. And he’s another example of the alliterative meme.

“The laziest boy will work like a beaver when he has a pleasing object in view… [A]ny well defined purpose kept clearly in mind will aid you in overcoming your apparently natural antipathy to hard work.”

Marxists talk about the “naturalizing” effect of ideology; here we see this sort of thing stated plainly. What seems natural (antipathy to hard work) is unnatural; what seems unnatural (beavering away) is natural.

Brownie: The Engineer of Beaver Brook is a 1927 illustrated children’s book that I haven’t read.

RED ALDER: I’m quite intrigued by Ska-Denge (Beaver for Revenge), a 1929 novel by Maine’s Lou Rogers (1879–1952), a cartoonist, illustrator, writer, storyteller, public speaker, radio host, and political activist. She seems pretty amazing. Our hero is Red Alder, “the chief of a brave and shrewd beaver tribe,” who fiercely takes on all manner of wildcats, weasels, eagles and other predatory types.

“Does the work of at least five men.”

Walt Disney’s Silly Symphony series and other animated musical short films of the Twenties offer us plenty of entertaining and instructive beaver-themed material. I haven’t (yet) seen earlier examples, by the way, of the beaver depicted as a team-worker.

- In Autumn, a 1930 Silly Symphony drawn by the great Ub Iwerks, we find a colony of beavers working in a perfectly choreographed, almost mechanized fashion. The beavers’ status as nature’s engineers is emphasized to humorous effect by various set pieces: e.g., one beaver uses another as a wheelbarrow or crane. What’s particularly interesting, here, is the fact that all of the animals (except for a solo porcupine) are working as teams — but their teamwork has a different flavor, depending on the species. The squirrels are antic and playful, the crows sly and sinister. This serves to emphasize the relatively no-nonsense, work-will-set-you-free character of the beavers’ labor. Here’s the film:

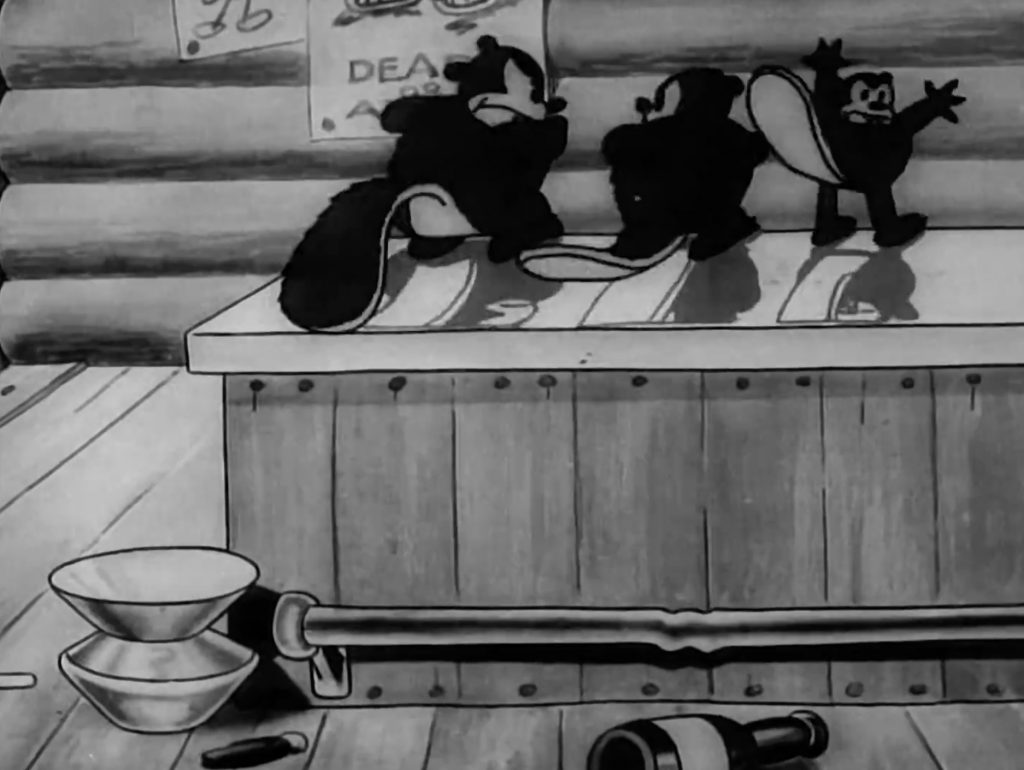

- Then there’s Big Man from the North, a 1931 Looney Tunes joint starring Bosko, a character — a racist caricature, whose catchphrase was, “Mmmm! Dat sho’ is fine!” — created by animators Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising. It’s a Mountie story, in which Bosko must make his way through the howling Canadian winter to a remote saloon and capture a wanted felon. There is a dancing and scatting scene, starring Bosko, in which beavers use their tails as percussion instruments. Here we are seeing two memes in one, really: beavers as Canadians, and beavers working together in unity — striving for perfection, even in a fun scene. Here’s the film:

- Walt Disney’s 1931 Silly Symphony The Busy Beavers, finally, extrapolates from the beaver scenes in Autumn to a full-on beaver worker’s paradise. Scores of beavers perform the same economical gestures — building a dam together, and lodges on their own. Beavers use each other as tools, again. There is a certain amount of dancing involved in each procedure; this is unalienated labor. Interestingly, one solitary beaver must act alone — self-sacrificially — in order to save the colony. Here’s the film:

There’s a Fordist-Taylorist aspect to the busy beavers of the Twenties, isn’t there? In the past, man had come first, but in the future the system must. One can’t help but think of Stalin’s efforts in the Soviet Union — the USSR was officially formed in 1922; Stalin assumed leadership in 1924 — during the same time period. (A 1924 Stalin quote: “American efficiency is that indomitable force which neither knows nor recognizes obstacles; which continues on a task once started until it is finished, even if it is a minor task; and without which serious constructive work is inconceivable.”) Under Stalin, the country underwent agricultural collectivization and rapid industrialization, creating a centralized command economy. The problems associated with these policies happened at the very end of the Twenties, and the Great Purge that followed happened at the beginning of the Thirties.

Another note about this cartoon beavers. They’re cute! Cuter than real beavers. But… not as cute as Mickey Mouse, say. They still look a bit ferocious, bear-like even. This will change in the Thirties, though.

Paddletail The Beaver and His Neighbors is a 1931 children’s book I haven’t read.

The Silver Beaver Award, introduced in 1931, is a council‐level distinguished service award of the Boy Scouts of America. Boy Scouts were encouraged to follow the examples set by tutelary creatures like the beaver…

Here’s further evidence of this sort of thing, a 1933 collectible British tobacco card that was part of a series of 50 explaining the symbolism of different Scout badges and awards. On the reverse side of this card, we read: “[T]he animals build dams, often of great strength, which are, perhaps, the most wonderful examples of skilled ‘team-work’ in the animal world.”

Coming up next: BEAVER 1934–1963

Here are a couple of footnotes to this section…

1

Big-headed beaver mascots, like MIT’s “TIM” or Oregon State’s Benny, aren’t all that exaggerated, really.

⏎

2

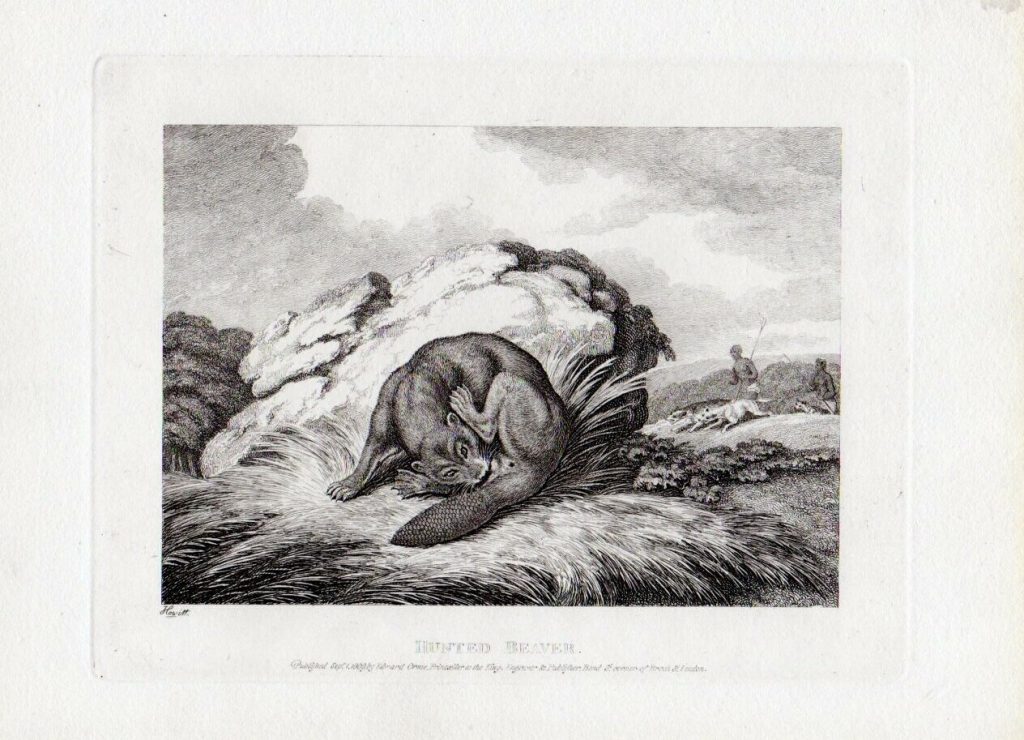

It was long believed that the castor sacs, located on the outside of its body, are the beaver’s testicles, which are actually on the inside. According to ancient folklore, the beaver would, when hunted, chew its testicles off in order to escape with its life. This far-fetched notion, which is predicated on the assumption that the beaver understands why it’s being hunted, and which we find in one of the fables ascribed to Aesop, is illustrated, for example, in the 1811 print shown above. Long before we admired its work ethic, pleasure-fearing Christians extolled the beaver for what they mistakenly believed to be its self-sacrificing renunciation. OK…

⏎

3

Above: a 1925 issue of The Beaver, a Journal of Progress, published by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The beaver fur trade was crucial to Canada; so much so that in 1678 the Hudson’s Bay Company put four beavers on the shield of its coat of arms. The monthly digest shown here was founded in 1920. (In 2010, the magazine changed its name to Canada’s History — because the publishers were fed up with all the snickering.)

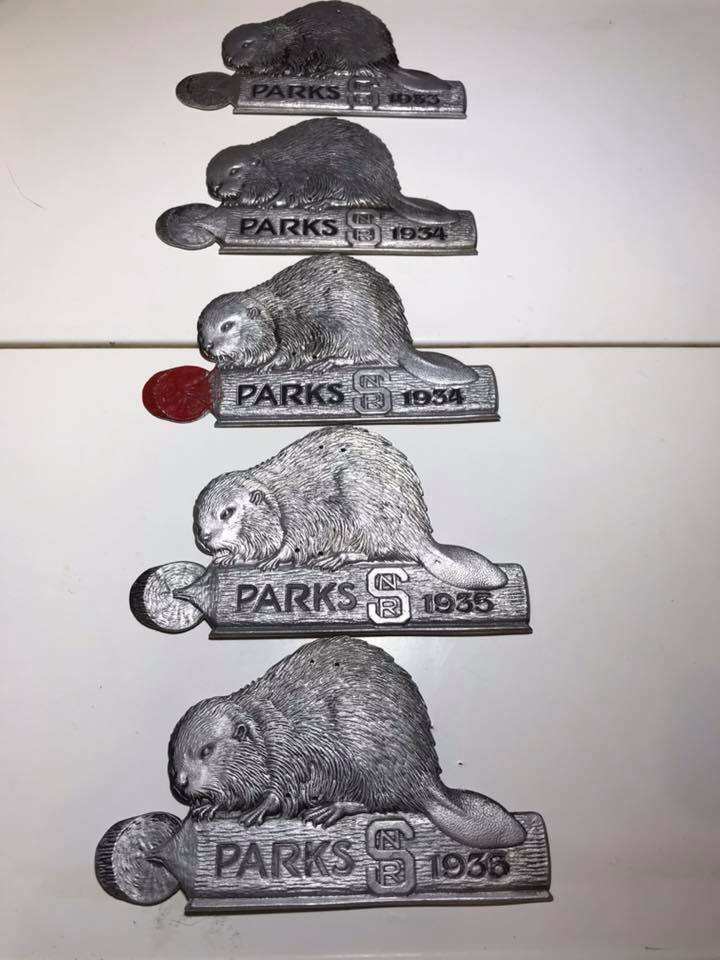

It wasn’t just the Hudson’s Bay Company that celebrated the beaver. When Montréal was incorporated in 1833, a beaver topped its coat of arms; a beaver graced Canada’s first postage stamp in 1851; and a beaver has appeared on the reverse of the country’s five-cent coin since the mid-1930s. In 1975, the beaver was declared Canada’s national animal.

Many companies in Canada have used a beaver as part of the company name or logo. For example, see the Canadian Pacific Railway company’s logo:

Here’s a 1964 Canadian edition of the US cereal Sugar Smacks:

And here’s a Canadian energy drink brand, introduced in 2005:

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.