The Zayat Kiss (6)

By:

October 16, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the sixth and final installment of our serialization of Sax Rohmer’s story “The Zayat Kiss.”

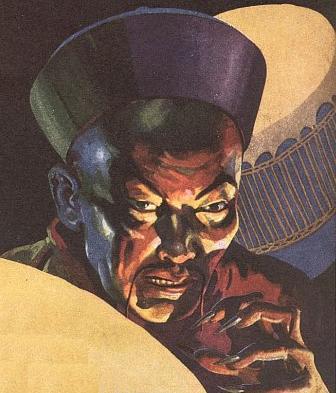

After the bloody Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which was sparked by secret societies in China whose aim was to eradicate Western and Christian influence in that country, a “Yellow Peril” panic briefly spread in the West. Sax Rohmer (Arthur Henry Ward) was a British journalist who haunted London’s Chinatown during that period; “The Zayat Kiss,” published in 1912, is set in that milieu. This story would be repurposed as the first three chapters of Rohmer’s popular novel The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu (1913; in the US: The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu), the first of a long series. Rohmer’s master criminal character, Fu Manchu, has since inspired depictions of sinister Asiatic science-fiction villains from Ming the Merciless to Dr. No, to Iron Man’s enemy The Mandarin.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

“My God! How horrible!” I exclaimed, and glanced apprehensively into the dusky shadows of the room. “What is your theory respecting this creature — what shape, what color?”

“It is something that moves rapidly and silently. I have observed that the rear of this house is ivy covered right up to and above your bedroom. Let us make ostentatious preparations to retire, and I think we may rely upon Fu-Manchu’s servants to attempt my removal, at any rate — if not yours.”

“But, my dear fellow, it is a climb of thirty-five feet at the very least!”

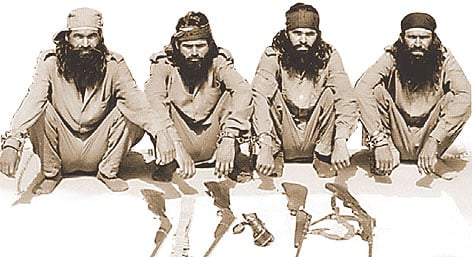

“You remember the cry in the back lane? It suggested something to me, and I tested my idea — successfully. It was the cry of a dacoit. Oh, dacoity, though quiescent, is by no means extinct. Fu-Manchu has dacoits in his train, and probably it is one who operates the Zayat Kiss, since it was a dacoit who watched the window of the study this evening. To such a man an ivy-covered wall is a grand staircase.”

The clock across the common struck two.

Having removed all traces of the scent of the orchid from our hands with a solution of ammonia. Smith and I had followed the program laid down. It was an easy matter to reach the rear of the house, by simply climbing a fence, and we did not doubt that, seeing the light go out in the front, our unseen watcher would proceed to the back. The room was a large one, and we had made up my camp bed at one end, stuffing odds and ends under the clothes to lend the appearance of a sleeper, which device we also had adopted in the case of the larger bed. The perfumed envelope lay upon a little coffee table in the center of the floor, and Smith, with an electric pocket lamp, a revolver, and a brassy beside him, sat on cushions in the shadow of the wardrobe. I occupied a post between the windows.

The distant clock struck a quarter-past two. A slight breeze stirred the ivy.

Something rose, inch by inch, above the sill of the westerly window. I could see only its shadow, but a sharp, sibilant breath from Smith told me that he, from his post, could see the cause of the shadow.

Every nerve in my body seemed to be strung tensely. I was icily cold, expectant, and prepared for whatever horror was upon us.

The shadow became stationary. The dacoit was studying the interior of the room.

Then it suddenly lengthened, and, craning my neck to the left, I saw a lithe, black-clad form, surmounted by a yellow face, sketchy in the moonlight, pressed against the window panes!

One thin, brown hand appeared over the edge of the lowered sash, which it grasped, and then another. The man made absolutely no sound whatever. The second hand disappeared — and reappeared. It held a small square box.

There was a very faint click.

The dacoit swung himself below the window with the agility of an ape as, with a dull, sickening thud, something dropped upon the carpet!

“Stand still, for your life!” came Smith’s voice, high pitched.

A beam of white light leaped out across the room and played fully upon the coffee table in the center.

Prepared as I was for something horrible, I know that I paled at sight of the thing that was running round the edge of the envelope.

It was an insect, full six inches long, and of a vivid, venomous red color! It had something of the appearance of a great ant, with its long, quivering antennae and its febrile, horrible vitality; but it was proportionately longer of body and smaller of head, and had numberless rapidly moving legs. In short, it was a giant centipede, apparently of the Scolopendra group, but of a form quite new to me. These things I realized in one breathless instant; in the next — Smith had dashed the thing’s poisonous life out with one straight, true blow of the golf club!

I leaped to the window and threw it widely open, feeling a silk thread brush my hand as I did so. A black shape was dropping with incredible agility from branch to branch of the ivy, and without once offering a mark for a revolver shot, it merged into the shadows beneath, the trees of the garden.

As I turned and switched on the light Nayland Smith dropped limply into a chair, leaning his head upon his hands. Even that grim courage had been tried sorely.

“Never mind the dacoit, Petrie,” he said. “Nemesis will know where to find him. We know now what causes the mark of the Zayat Kiss. Therefore science is richer for our first brush with the enemy, and the enemy is poorer — unless he has any more unclassified centipedes. I understand now something that has been puzzling me since I heard of it — Sir Crichton’s stifled cry. When we remember that he was almost past speech, it is reasonable to suppose that his cry was not “The red hand!’ but ‘The red ant!’ Petrie, to think that I failed by less than an hour to save him from such an end!”

The body of a lascar, dressed in the manner usual on the P.& 0. boats, was recovered from the Thames off Tilbury by the river police at 6 a.m. this morning. It is supposed that the man met with an accident in leaving his ship.

Nayland Smith passed me the evening paper and pointed to the above paragraph.

“For ‘lascar’ read ‘dacoit,'” he said. “Our last night’s visitor, fortunately for us, failed to follow his instructions. Also, he lost the centipede and left a clue behind him. Dr. Fu-Manchu does not overlook such lapses.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.