IN CAHOOTS (3)

By:

October 26, 2022

Third in a series of posts via which HILOBROW’s Josh Glenn offers anecdotes and advice from his own creative career.

IN CAHOOTS: GOING INDIE | MATERIAL CULTURE | COMMUNITY BUILDING | WALKING THE TIGHTROPE | OBJECT-ORIENTED | PARTNERING | CAMARADERIE.

I worked at Utne Reader from late 1996 to early 1998 — for about a year and a half. There were other things I didn’t like about working there, too, but when it comes to creative expression, I discovered that there (for me) is something dissatisfying about working for a “real” magazine. Not that Utne Reader, which was independently published, and which aimed to surface the best ideas emerging from the alt.culture, was a mainstream periodical. But its print run was over 300,000… and having begun my publishing career in the low-circulation zine world, I discovered that something felt… off about that dynamic.

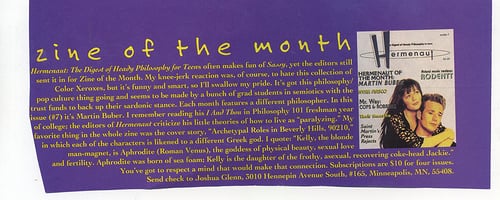

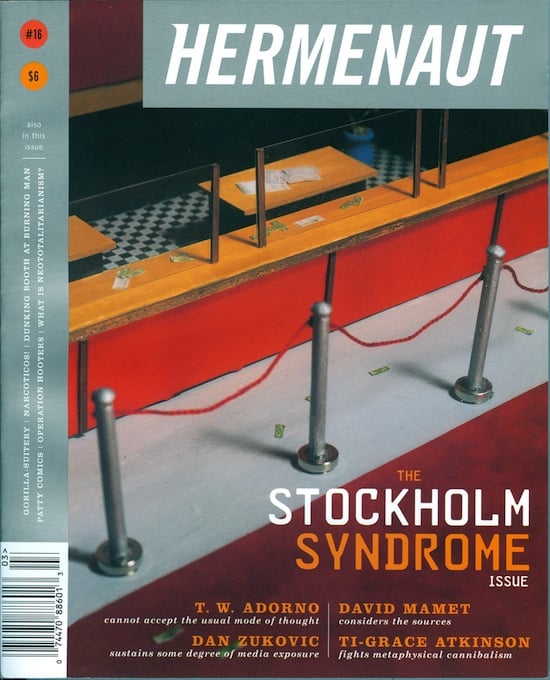

The articles and features that I wrote and edited for Utne Reader reached 300,000 readers — more, if you believe what the circulation folks claimed about multiple people reading the same copy of each issue. This was in stark contrast with the 500 readers of Hermenaut #7 (“Unheimlich,” winter 1993–1994); the 1,000 readers of #8 (“Conspiracies,” some time in 1994 — our circulation jumped after Hermenaut was named “zine of the month” by Sassy; the 2,000 readers of #10 (“Popular Culture,” some time in 1995 — whose editorial Naomi Klein took issue with, see previous post);

I also wrote for the Minneapolis/St. Paul-based music/culture magazine Cake, edited by my friend Chank Diesel, at this time. For example, I was the first journalist to report in depth on the “Cocktail Nation” trend; the story was reprinted in Utne Reader (Nov./Dec. 1994) and picked up by Time too. I liked writing for a local periodical — again, there was a sense of fairly intimate community.

At a large magazine or newspaper, the editorial staffers’ sphere of influence is very restricted. Editors and writers barely interact with the designers, much less circulation, marketing, ad sales, etc. (Ad sales, OK, that makes sense at a place like the Boston Globe — I get it.) More dispiritingly, magazine writing is like shouting from a mountaintop; it’s an impressive, effective, ego-boosting platform — but it’s so anonymous. Compared, that is to say, with zine publishing — where you strongly feel that you are writing for a community, among whom many are fellow zine publishers.

I’m not just talking about the sense that one intimately understands one’s audience. For me, writing means working out what I think and believe. My experience at Utne Reader reinforced my intuitive conviction that doing so in conversation — implicit or explicit — with others is good and right, for me. Note that “for me” — this isn’t a universal pronunciamento.

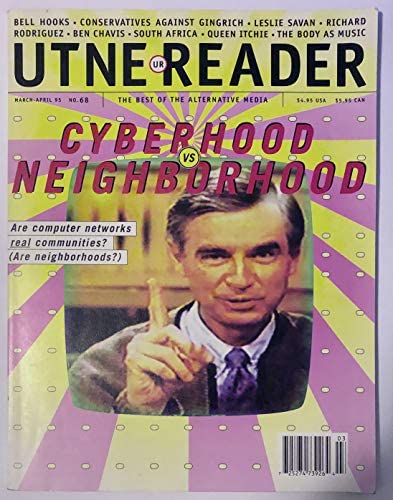

The World Wide Web, which began to emerge around the time I was at Utne Reader, promised to be an extraordinary medium via which to conduct the sort of publishing enterprise I had in mind. Griff Wigley, who now works with organizations interested in using online tools to deepen citizen engagement, was the Web guy at Utne Reader, back then. He helped me organize online salons for the magazine; in doing so, I became excited about the possibilities for online “community,” which I perceived — though not without many caveats — as an excellent way to support cool projects IRL. I even co-edited an Utne Reader cover feature [March/April 1995] on online vs. offline community; this essay by John Perry Barlow was its centerpiece.

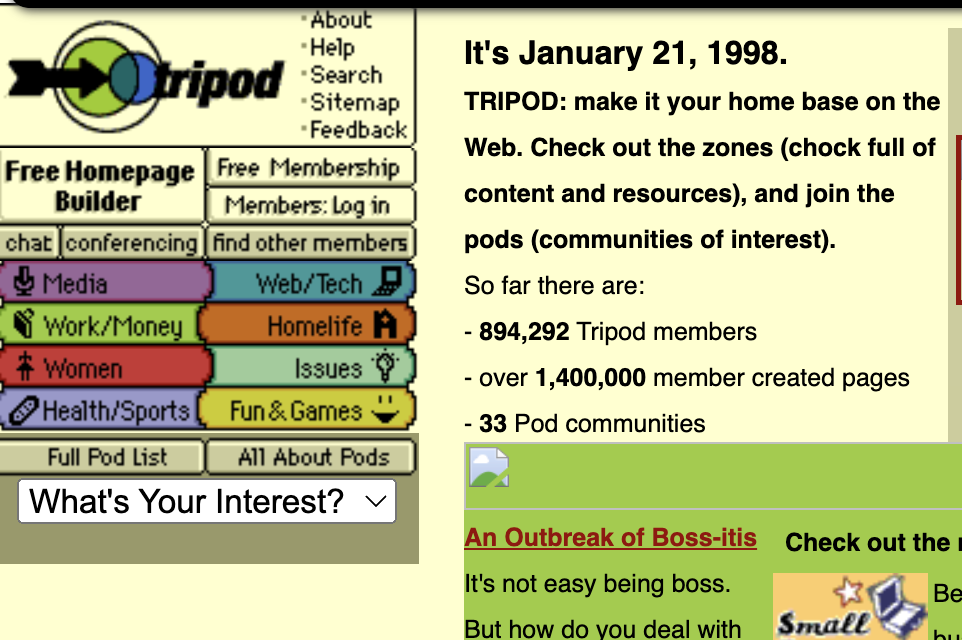

When I was offered a job, in western Massachusetts, as editor/producer for a startup dotcom (Tripod) that aimed to provide tools and server space allowing users to build their own websites and build communities of shared interest, it seemed like a good fit. Susan and I sold our house in northeast Minneapolis and moved to a cabin in New Ashford — just outside Williamstown.

I worked at Tripod from late 1996 to early 1998 — again, about a year and a half. (No full-time job has ever proven to be a perfect fit, for me.) I worked with some amazing people — including Dan Reines, Emma Taylor, and Ethan Zuckerman, with whom I’ve remained fairly close. I learned so much — in particular, I learned how fragile online community is. All of the benefits and drawbacks that we now face with social media were there from the beginning, in inchoate form, at Tripod. Giving everyone a publishing platform is a worthy, even a noble idea… but without enforced community guidelines, human moderation, and mutual goodwill and trust, all of which are expensive and time-consuming to establish and maintain, you’re not really building community.

PS: Because of my experience in developing and sustaining online communities, I was invited by my friend and former colleague Jon Spayde to contribute the chapter on “online salons” to the 2001 book Salons: The Joy of Conversation (an Utne Reader effort). In it — via interviews with other online community-builders — I make these points.

Susan and I had our first child, Sam, in 1998. Tripod was acquired by a publicly traded company around the same time, so I cashed in my stock options, and we moved to Boston. Instead of buying a home, which would have been sensible, I plowed every penny of my dotcom loot into the final few issues of Hermenaut. (I don’t regret it; I’m incredibly proud of those issues. I also need to thank Clarke Cooper and Marilyn Snell for donating to the cause.) This was a richly rewarding period in my life. Here are a few snapshots from that era of Hermenaut, and here’s info on issues #11/12 and #13 (published while I was at Tripod), and #s 14 through 16.

Many of the folks with whom I collaborated on Hermenaut during this period — including A.S. Hamrah, Matthew Battles, Jerrold Freitag, Katie Hennessey, Mimi Lipson, James Parker, Lynn Peril, Dan Reines, Greg Rowland, Marilyn Snell, Lisa Carver, Tom Frank, Jen Collins, Patrick Smith, Chris Fujiwara, Clarke Cooper, Ingrid Schorr, Heather Kasunick, Michael Lewy, Tony Leone, Lydia Millet, Matthew De Abaitua, Mark Frauenfelder — have continued to be my collaborators, on my various book projects, for example, as well as right here at HILOBROW.

For a brief, glorious moment, I was doing exactly what I’d dreamed of doing — and doing so with a dream team of creative collaborators. But in 2000, around the time that our second son, Max, was born, I went into credit-card debt attempting to keep Hermenaut afloat. I needed to make a proper living. Which meant “splitting the stream” – a Ghostbusters-derived metaphor. I could no longer remain focused entirely on creative, yet inadequately remunerative work.

I did have another source of income, by that point. Here’s where my streams began to split.

In 1999 or perhaps a bit earlier, I began freelancing sporadically as a consulting semiotician for brands. My interest in branding was anthropological in nature — which is why commercial semiotics, which involves consulting to brand teams, creative agencies, and consumer insights managers about unspoken cultural and category “codes,” has proven a pretty good fit. I’m still doing it, over twenty years later.

I’d been scouted by Greg Rowland, one of England’s original commercial semioticians, whom I’d met via a mutual friend — Tom Hodgkinson, editor of The Idler. (I’d met Tom through James Parker, who’d been couch-surfing in the apartment below me and Susan, when I was earning my teaching degree and starting Hermenaut.) Greg introduced me to his former colleague, Malcolm Evans, another UK commercial semiotician; Malcolm would cofound the agency Space Doctors in 2001 — around the time that Hermenaut went bankrupt.

These were early days for the commercial semiotics discipline, and until about five years from then there wouldn’t be enough work for me to make a living doing semiotics. Unless I went to work at a marketing agency as a staff semiotician — I’d been asked to apply for a few such positions. But… although I was interested in branding, design, and consumer behavior, among other aspects of material culture — I was deeply uninterested in actually working at a marketing agency.

What to do? If I went back into journalism, or went to work at an agency, would I ever find a way “cross the streams” again?

Next time: WALKING THE TIGHTROPE

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: SCHEMATIZING | IN CAHOOTS | JOSH’S MIDJOURNEY | POPSZTÁR SAMIZDAT | VIRUS VIGILANTE | TAKING THE MICKEY | WE ARE IRON MAN | AND WE LIVED BENEATH THE WAVES | IS IT A CHAMBER POT? | I’D LIKE TO FORCE THE WORLD TO SING | THE ARGONAUT FOLLY | THE PERFECT FLANEUR | THE TWENTIETH DAY OF JANUARY | THE REAL THING | THE YHWH VIRUS | THE SWEETEST HANGOVER | THE ORIGINAL STOOGE | BACK TO UTOPIA | FAKE AUTHENTICITY | CAMP, KITSCH & CHEESE | THE UNCLE HYPOTHESIS | MEET THE SEMIONAUTS | THE ABDUCTIVE METHOD | ORIGIN OF THE POGO | THE BLACK IRON PRISON | BLUE KRISHMA | BIG MAL LIVES | SCHMOOZITSU | YOU DOWN WITH VCP? | CALVIN PEEING MEME | DANIEL CLOWES: AGAINST GROOVY | DEBATING IN A VACUUM | PLUPERFECT PDA | SHOCKING BLOCKING.