Theodore Savage (9)

By:

May 6, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the ninth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

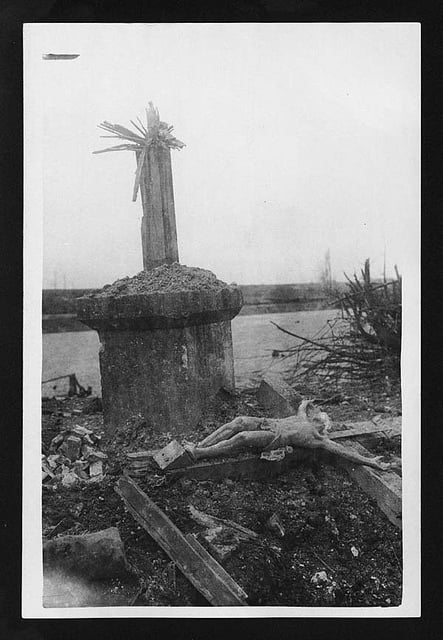

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

Those who had rifles fired at it and men in the foremost ranks went down, unheeded in the rush of their fellows; those who might have hesitated were thrust forward by the frantic need behind, and the torrent of misery broke against the little group of soldiers in a tumult of grappling and screeching. Women, like men, asserted their beast-right to food — when sticks and knives failed them, asserted it with claws and teeth; unhuman creatures, with eyes distended and wide, yelling mouths, went down with their fingers at each other’s throats, their nails in each other’s flesh…. Theodore clubbed a length of burnt wood and struck out… saw a man drop with a broken, bloody face and a woman back from him shrieking… then was gripped from behind, with an arm round his neck, and went down…. The famished creatures fought above his body and beat out his senses with their feet.

When life came back to him the sun was very low in the west. In his head little hammers beat intolerably and all his strained body ached with bruises as he raised himself, slowly and groaning, and leaned on an arm to look round. He lay much where he had fallen, but the soldiers, the crowd of human beasts, had vanished; the bare stretch of camp, still smoking in places, was silent and almost deserted. Two or three bending and intent figures were hovering round the charred masses of wreckage — moving slowly, stopping often, peering as they walked and thrusting their hands into the ashes, in the hope of some fragment that those who searched before them had missed. A woman lay face downwards with her dead arm flung across his feet; further off were other bodies — which the searchers passed without notice. Three or four were in uniform, the bodies of men who had once been his comrades; others, for the benefit of the living, had been stripped, or half-stripped, of their clothing.

He lifted himself painfully and crawled on hands and knees, with many groans and halts, to the stream that had formed one border of the camp — where he drank, bathed his head and washed the dried blood from his scratches. With a measure of physical relief — the blessing of cool water to a burning head and throat — came a clearer understanding and, with clearer understanding, fear…. He knew himself alone in chaos.

As soon as he might he limped back to the smouldering wood-heaps and accosted a woman who was grubbing in a mess of black refuse. Did she know what had become of the soldiers? Which way they had gone when they left? The woman eyed him sullenly, mistrustful and resenting his neighbourhood — knew nothing, had not seen any soldiers — and turned again to grub in her refuse. A skeleton of a man was no wiser; had only just turned off the road to search, did not know what had happened except that there must have been a fight — but it was all over when he came up. He also had seen no soldiers — only the dead ones over there…. Theodore saw in their eyes that they feared him, were dreading lest he should compete with them for their possible treasure of refuse.

For the time being a sickly faintness deprived him of all wish for food; he left the sullen creatures to their clawing and grubbing, went back to the water, drank and soused once more, then crept farther off in search of a softer ground to lie on. After a few score yards of painful dragging and halting, he stretched himself exhausted on a strip of dank grass at the roadside — and dozed where he fell until the morning.

With sunrise and awakening came the pangs of sharp hunger, and he dragged himself limping through mile after mile in search of the wherewithal to stay them. He was giddy with weakness and near to falling when he found his first meal in a stretch of newly-burned field — the body of a rabbit that the fire had blackened as it passed. He fell upon it, hacked it with his clasp-knife and ate half of it savagely, looking over his shoulder to see that no one watched him; the other half he thrust into his pocket to serve him for another meal. He had learned already to live furtively and hide what he possessed from the neighbours who were also his enemies. Next day he fished furtively — with a hook improvised out of twisted wire and worm-bait dug up by his clasp-knife; lurking in bushes on the river-bank, lest others, passing by, should note him and take toll by force of his catch.

He lived thenceforth as men have always lived when terror drives them this way and that, and the earth, untended, has ceased to yield her bounties; warring with his fellows and striving to outwit them for the remnant of bounty that was left. He hunted and scraped for his food like a homeless dog ; when found, he carried it apart in stealth and bolted it secretly, after the fashion of a dog with his offal. In time all his mental values changed and were distorted: he saw enemies in all men, existed only to exist — that he might fill his stomach — and death affected him only when he feared it for himself. He had grown to be self-centred, confined to his body and its daily wants and that side of his nature which concerned itself with the future and the needs of others was atrophied. He had lost the power of interest in all that was not personal, material and immediate; and, as the uncounted days dragged out into weeks, even the thought of Phillida, once an ever-present agony, ceased to enter much into his daily struggle to survive. He starved and was afraid: that was all. His life was summed up in the two words, starvation and fear.

At night, as a rule, he sheltered in a house or deserted farm-building that stood free for anyone to enter — sometimes alone, but as often as not in company. Starved rabble, as long as it hunted for food, avoided its rivals in the chase; but when night, perforce, brought cessation of the hunt, the herding instinct reasserted itself and lasted through the hours of darkness. As autumn sharpened, guarded fires were lit in cellars where they could not be seen from above and fed with broken furniture, with fragments of doors and palings; and one by one, human beasts would slink in and huddle down to the warmth — some uncertainly, seeking a new and untried refuge, and others returning to their shelter of the night before. The little gangs who shared fire and roof for the space of a night never ate in each other’s company; food was invariably devoured apart, and those who had possessed themselves of more than an immediate supply would hide and even bury it in a secret place before they came in contact with their fellows. Hence no gang, no little herd, was permanent or contained within itself the beginnings of a social system; its members shared nothing but the hours of a night and performed no common social duties. A face became familiar because seen for a night or two in the glow of a common fire; when it vanished none knew — and none troubled to ask — whether a man had died between sunrise and sunset or whether he had drifted further off in his daily search for the means to keep life in his body. When a man died in the night, with others round him, the manner of his ending was known; otherwise he passed out of life without notice from those who yet crawled on the earth…. With morning the herd of starvelings that had sheltered together broke up and foraged, each man for himself and his own cravings; rooted in fields and trampled gardens, crouched on river-banks fishing, laid traps for vermin, ransacked shops and houses where scores had preceded them…. And some, it was muttered — as time went on and the need grew yet starker — fed horribly… and therefore plentifully….

There were nights — many nights — when a herd broke in panic from its shelter and scattered to the winds of heaven at an alarm of the terror overhead; and always, as starvation pressed, it dwindled — by death and the tendency to dissolve into single nomads, who (such as survived) regrouped themselves elsewhere, to scatter and re-group again…. With repeated wandering — now this way, now that, as hope and hunger prompted — went all sense of direction and environment; the nomads, hunting always, drifted into broken streets or dead villages and through them to the waste of open country — not knowing where they were, in the end not caring, and turned back by a river or the sea.

The sight or suspicion of food and plunder would always draw vagrancy together in crowds; district after district untouched by an enemy had been swept out of civilized existence by the hordes which fell on the remnants of prosperity and tore them; which ransacked shops and dwellings, slaughtered sheep, horses, cattle and devoured them and, often enough, in a fury of destruction and vehement envy, set light to houses and barns lest others might fare better than themselves. But when flocks, herds and storehouses had vanished, when agriculture, like the industry of cities, had ceased to exist and nothing remained to devour and plunder, the motive for common action passed. With equality of wretchedness union was impossible, and every man’s hand against his neighbour; if groups formed, here and there, of the stronger and more brutal, who joined forces for common action, they held together only for so long as their neighbours had possessions that could be wrested from them — stores of food or desirable women; once the neighbours were stripped of their all and there was nothing more to prey on, the group fell apart or its members turned on each other. In the life predatory man had ceased to be creative; in a world where no one could count on a morrow, construction and forethought had no meaning.

In a world where all were vagabond and brutal, where each met each with suspicion and all men were immersed in the intensity of their bodily needs, very few had thoughts to exchange. Mentally, as well as actually, they lived to themselves and where they did not distrust they were indifferent; the starvelings who slunk into shelter that they might huddle for the night round a common fire found little to say to one another. As human desire concentrated itself on the satisfaction of animal cravings, so human speech degenerated into mere expression of those cravings and the emotions aroused by them. Only once or twice while he starved and drifted did Theodore talk with men who sought to give expression to more than their present terrors and the immediate needs of their bodies, who used speech that was the vehicle of thought.

One such he remembered — met haphazard, as all men met each other — when he sheltered for an autumn night on the outskirts of a town left derelict. With falling dusk came a sudden sharp patter of rain and he took refuge hurriedly in the nearest house — a red-brick villa, standing silent with gaping windows. What was left of the door swung loosely on its hinges — half the lower panels had been hacked away to serve as firewood; the hall was befouled with the feet of many searchers and of the furniture remained but a litter of rags and fragments that could not be burned.

He thought the place empty till he scented smoke from the basement; whereupon he crept down the stairs, soft-footed and alert, to discover that precaution was needless. There was only one occupant of the house, a man plainly dying; a livid hollow-eyed skeleton who coughed and trembled as he knelt by the grate and tried to blow damp sticks into a flame. Theodore, in his own interests, took charge of the fire, ransacked the house for inflammable material and tore up strips of broken boarding that the other was too feeble to wrestle with. When the blaze flared up, the sick man cowered to it, stretched out his hands — filthy skin-covered bones — and thanked him; whereat Theodore turned suddenly and stared. It was long — how long?— since any man had troubled to thank him; and this man, for all his verminous misery, had a voice that was educated, cultured…. Something in the tone of it — the manner — took Theodore back to the world where men ate courteously together, were companions, considered each other ; and instinctively, almost without effort, he offered a share of his foraging. The offer was refused, whereat Theodore wondered still more; but the man, near death, was past desire for food and shook his head almost with repulsion. Perhaps it was the fever that had turned him against food that loosened his tongue and set him talking — or perhaps he, also, by another’s voice and manner, was reminded of his past humanity.

“‘My mind to me a kingdom is,'” he quoted suddenly. “Who wrote that — do you remember?”

“No,” Theodore said, “I’ve forgotten.” He stared at the cowering, hunched figure with its shaking hands stretched to the blaze. The man, it might be, was mad as well as dying — he had met many such in his wanderings; babbling of verse as someone — who was it?— had babbled in dying of green fields.

“‘My mind to me a kingdom is,'” the sick man repeated. “Well, even if we’ve forgotten who wrote it, there’s one thing about him that’s certain: he didn’t know what we know — hadn’t lived in our kind of hell. The place where you haven’t a mind — only fear and a stomach…. The flesh and the devil — hunger and fear; they haven’t left us a world!… But if there’s ever a world again, I believe I shall have learned how to write. Now I know what we are — the fundamentals and the nakedness….”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.