The Scarlet Plague (3)

By:

February 2, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the third installment of our serialization of Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague. New installments will appear each Thursday for 12 weeks.

London’s post-apocalyptic novel is partly set in 2013; 2012 marks the centennial of its first serialization. In May, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of The Scarlet Plague, checked against the 1915 first published edition (Macmillan), with an introduction by science fiction author (and HiLobrow cofounder) Matthew Battles. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “You are true savages. Already has begun the custom of wearing human teeth. In another generation you will be perforating your noses and ears and wearing ornaments of bone and shell. I know. The human race is doomed to sink back farther and farther into the primitive night ere again it begins its bloody climb upward to civilization.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

CHAPTER TWO (excerpt 1 of 2)

The old man showed pleasure in being thus called upon. He cleared his throat and began.

“Twenty or thirty years ago my story was in great demand. But in these days nobody seems interested —”

“There you go!” Hare-Lip cried hotly. “Cut out the funny stuff and talk sensible. What’s interested? You talk like a baby that don’t know how.”

“Let him alone,” Edwin urged, “or he’ll get mad and won’t talk at all. Skip the funny places. We’ll catch on to some of what he tells us.”

“Let her go, Granser,” Hoo-Hoo encouraged; for the old man was already maundering about the disrespect for elders and the reversion to cruelty of all humans that fell from high culture to primitive conditions.

The tale began.

“There were very many people in the world in those days. San Francisco alone held four millions —”

“What is millions?” Edwin interrupted.

Granser looked at him kindly.

“I know you cannot count beyond ten, so I will tell you. Hold up your two hands. On both of them you have altogether ten fingers and thumbs. Very well. I now take this grain of sand — you hold it, Hoo-Hoo.” He dropped the grain of sand into the lad’s palm and went on. “Now that grain of sand stands for the ten fingers of Edwin. I add another grain. That’s ten more fingers. And I add another, and another, and another, until I have added as many grains as Edwin has fingers and thumbs. That makes what I call one hundred. Remember that word — one hundred. Now I put this pebble in Hare-Lip’s hand. It stands for ten grains of sand, or ten tens of fingers, or one hundred fingers. I put in ten pebbles. They stand for a thousand fingers. I take a mussel-shell, and it stands for ten pebbles, or one hundred grains of sand, or one thousand fingers….”

And so on, laboriously, and with much reiteration, he strove to build up in their minds a crude conception of numbers. As the quantities increased, he had the boys holding different magnitudes in each of their hands. For still higher sums, he laid the symbols on the log of driftwood; and for symbols he was hard put, being compelled to use the teeth from the skulls for millions, and the crab-shells for billions. It was here that he stopped, for the boys were showing signs of becoming tired.

“There were four million people in San Francisco — four teeth.”

The boys’ eyes ranged along from the teeth and from hand to hand, down through the pebbles and sand-grains to Edwin’s fingers. And back again they ranged along the ascending series in the effort to grasp such inconceivable numbers.

“That was a lot of folks, Granser,” Edwin at last hazarded.

“Like sand on the beach here, like sand on the beach, each grain of sand a man, or woman, or child. Yes, my boy, all those people lived right here in San Francisco. And at one time or another all those people came out on this very beach — more people than there are grains of sand. More — more — more. And San Francisco was a noble city. And across the bay — where we camped last year, even more people lived, clear from Point Richmond, on the level ground and on the hills, all the way around to San Leandro — one great city of seven million people.—Seven teeth… there, that’s it, seven millions.”

Again the boys’ eyes ranged up and down from Edwin’s fingers to the teeth on the log.

“The world was full of people. The census of 2010 gave eight billions for the whole world — eight crab-shells, yes, eight billions. It was not like to-day. Mankind knew a great deal more about getting food. And the more food there was, the more people there were. In the year 1800, there were one hundred and seventy millions in Europe alone. One hundred years later — a grain of sand, Hoo-Hoo — one hundred years later, at 1900, there were five hundred millions in Europe — five grains of sand, Hoo-Hoo, and this one tooth. This shows how easy was the getting of food, and how men increased. And in the year 2000 there were fifteen hundred millions in Europe. And it was the same all over the rest of the world. Eight crab-shells there, yes, eight billion people were alive on the earth when the Scarlet Death began.

“I was a young man when the Plague came — twenty-seven years old; and I lived on the other side of San Francisco Bay, in Berkeley. You remember those great stone houses, Edwin, when we came down the hills from Contra Costa? That was where I lived, in those stone houses. I was a professor of English literature.”

Much of this was over the heads of the boys, but they strove to comprehend dimly this tale of the past.

“What was them stone houses for?” Hare-Lip queried.

“You remember when your dad taught you to swim?” The boy nodded. “Well, in the University of California — that is the name we had for the houses — we taught young men and women how to think, just as I have taught you now, by sand and pebbles and shells, to know how many people lived in those days. There was very much to teach. The young men and women we taught were called students. We had large rooms in which we taught. I talked to them, forty or fifty at a time, just as I am talking to you now. I told them about the books other men had written before their time, and even, sometimes, in their time —”

“Was that all you did?— just talk, talk, talk?” Hoo-Hoo demanded. “Who hunted your meat for you? and milked the goats? and caught the fish?”

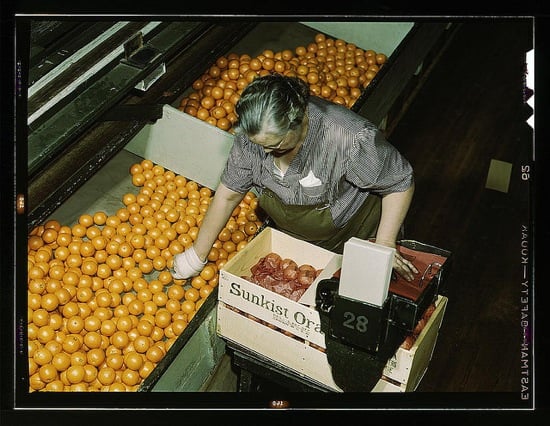

“A sensible question, Hoo-Hoo, a sensible question. As I have told you, in those days food-getting was easy. We were very wise. A few men got the food for many men. The other men did other things. As you say, I talked. I talked all the time, and for this food was given me — much food, fine food, beautiful food, food that I have not tasted in sixty years and shall never taste again. I sometimes think the most wonderful achievement of our tremendous civilization was food — its inconceivable abundance, its infinite variety, its marvellous delicacy. O my grandsons, life was life in those days, when we had such wonderful things to eat.”

This was beyond the boys, and they let it slip by, words and thoughts, as a mere senile wandering in the narrative.

“Our food-getters were called freemen. This was a joke. We of the ruling classes owned all the land, all the machines, everything. These food-getters were our slaves. We took almost all the food they got, and left them a little so that they might eat, and work, and get us more food —”

“I’d have gone into the forest and got food for myself,” Hare-Lip announced; “and if any man tried to take it away from me, I’d have killed him.”

The old man laughed.

“Did I not tell you that we of the ruling class owned all the land, all the forest, everything? Any food-getter who would not get food for us, him we punished or compelled to starve to death. And very few did that. They preferred to get food for us, and make clothes for us, and prepare and administer to us a thousand — a mussel-shell, Hoo-Hoo — a thousand satisfactions and delights. And I was Professor Smith in those days —Professor James Howard Smith. And my lecture courses were very popular — that is, very many of the young men and women liked to hear me talk about the books other men had written.

“And I was very happy, and I had beautiful things to eat. And my hands were soft, because I did no work with them, and my body was clean all over and dressed in the softest garments —” He surveyed his mangy goat-skin with disgust. “We did not wear such things in those days. Even the slaves had better garments. And we were most clean. We washed our faces and hands often every day. You boys never wash unless you fall into the water or go swimming.”

“Neither do you Granser,” Hoo-Hoo retorted.

“I know, I know, I am a filthy old man, but times have changed. Nobody washes these days, there are no conveniences. It is sixty years since I have seen a piece of soap. You do not know what soap is, and I shall not tell you, for I am telling the story of the Scarlet Death. You know what sickness is. We called it a disease. Very many of the diseases came from what we called germs. Remember that word — germs. A germ is a very small thing. It is like a woodtick, such as you find on the dogs in the spring of the year when they run in the forest. Only the germ is very small. It is so small that you cannot see it —”

NEXT WEEK: “The easier it was to get food, the more men there were; the more men there were, the more thickly were they packed together on the earth; and the more thickly they were packed, the more new kinds of germs became diseases.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

OUR THANKS: to io9, the Wall Street Journal blog Ideas Market, NPR’s Science Friday blog, Comic Critique, and others for talking up our project. And thanks, Twitter, for the HiLoBooks love.

READ: You are reading Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague. Also read our serialization of: Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail | H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.