OFF-TOPIC (73)

By:

September 23, 2025

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This episode, for a recurrent era of traumatizing times, an old story of childhood 3-D imprinting…

Human personality strives for uniqueness, but our collective gravity tends toward the definitive — Plato’s cosmic “forms” that all things and people are shadows of; Jung’s archetypes into whose categories we all fall; the iconic templates of crucifixes, coin-faces, famous-painting and movie-poster poses. History’s gatekeepers want parameters that are set in stone and stuck in our mind. But these days that can be rewritten in pixels, and there once came a time when the present was merely pressed in plastic.

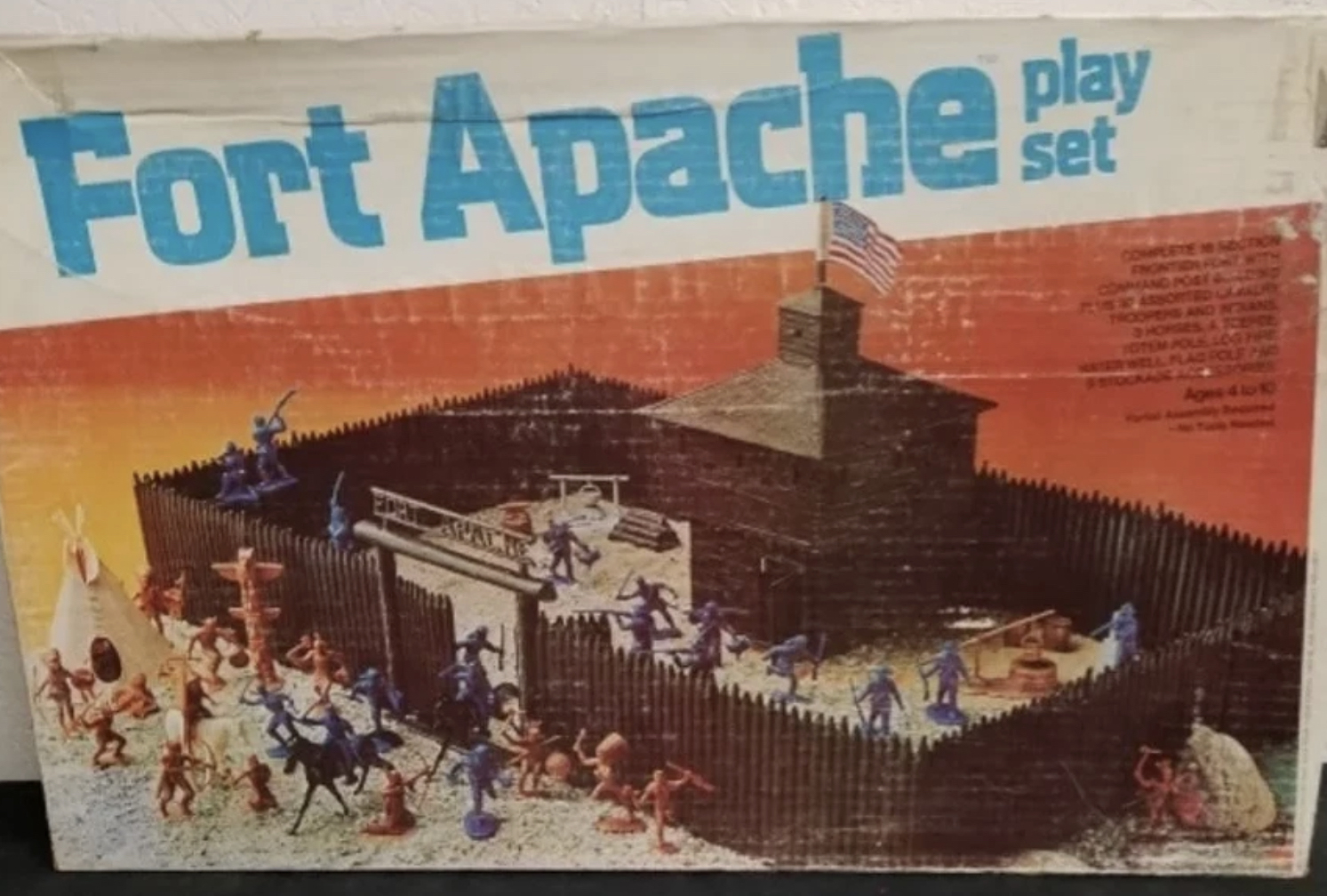

I was reminded of this by a post in Josh Glenn’s Not Today, eBay series, covering the strangely specific realism and profuse permutations (down to elaborate injuries and deaths) in sets of plastic action figurines by the seminal 20th-century toy company Marx. These would consist of hordes of miniature combatants or adventurers (soldiers, frontier-dwellers, cops-and-gangsters, cowboys-and-Natives, astronauts) that could be placed around a focal stage-set-in-a-box (which in some cases was the box, folded out) — wartime fortresses, prairie settlements, rocket-ports, medieval keeps.

Without joints, the characters were not posable, but extensively positionable; not endlessly, but Marx though of every situation for possible figure groupings; it’s strange to think of kids playing with these figures the way they crash Transformers together since all the articulations have been chosen beforehand, but they could certainly “play” god in composing the grand scheme of a battle. Meanwhile the configurations are finitely preordained, like DEFCONs 1 through 5; the other Platonic program, as blueprinted in The Republic, is to limit possibilities as a means of managing social order, and in the same way, Marx playsets offer a vast-feeling but eventually circumscribed set of options.

Some of this depends on context, the literal boxing-in of the metal mountains, castles, stockades, etc. the figures were designed to center on. At this scale and in these settings, the characters were, essentially, the things that happen to them, their function at the god’s-eye view of kids playing with them; they are elements in a composition.

But that was not their only context. Thousands of these sets were sold and possibly millions of kids played with them, but I was one of the millions who did not; when my sister and I were growing up our parents’ budget allowed strictly for piecemeal luxuries, so there might be bendable Major Matt Mason figures coming into the house but not his space station, individual Barbies but no Malibu DreamHouse.

Marx had this covered too: concurrently with their thumbnail-soldier playsets, they were marketing roughly action-figure-scale versions of those and other designs on their own; binfuls of them in candy stores, pharmacies, actual toyshops and other places where bulk cheap playthings would aggregate.

At this scale and devoid of accessorizing, the figures floated freely from nearly any context at all, for narratives to be assigned at will and signification to generate spontaneously. I had a “caveman” hoisting a boulder over his head to clobber who knows what animal, primal antagonist or evolutionary rival, my prized possession when I was 3. I had a knight, similarly raising a mace over his head, and an Arthurian figure with his helmet’s visor up, revealing his wizard’s mustache and wise bushy eyebrows, pointing magisterially to some unseen promised land; a pose, come to think of it, that could have been just mildly modified from the mold for one of Alexander Waverly, the head of intelligence on the Man from U.N.C.L.E. spy series, which Marx also licensed.

These appeared unpredictably in stores, mixed randomly in our houses, and gave a sense of uncompletable sets and unfinishable (and for that matter beginning-less) sagas. Their play value was mystifying, being immobile hard plastic, but at the same time they fascinated as a kind of compact sculpture garden. Only not like those we were used to being bored by on museum fieldtrips, but ones which strove to capture motion and expression rather than monumentalize stillness and emotional repose; animation in the most static of mediums, or maybe the moldable plastic signaled to the manufacturer a fundamental fluidity.

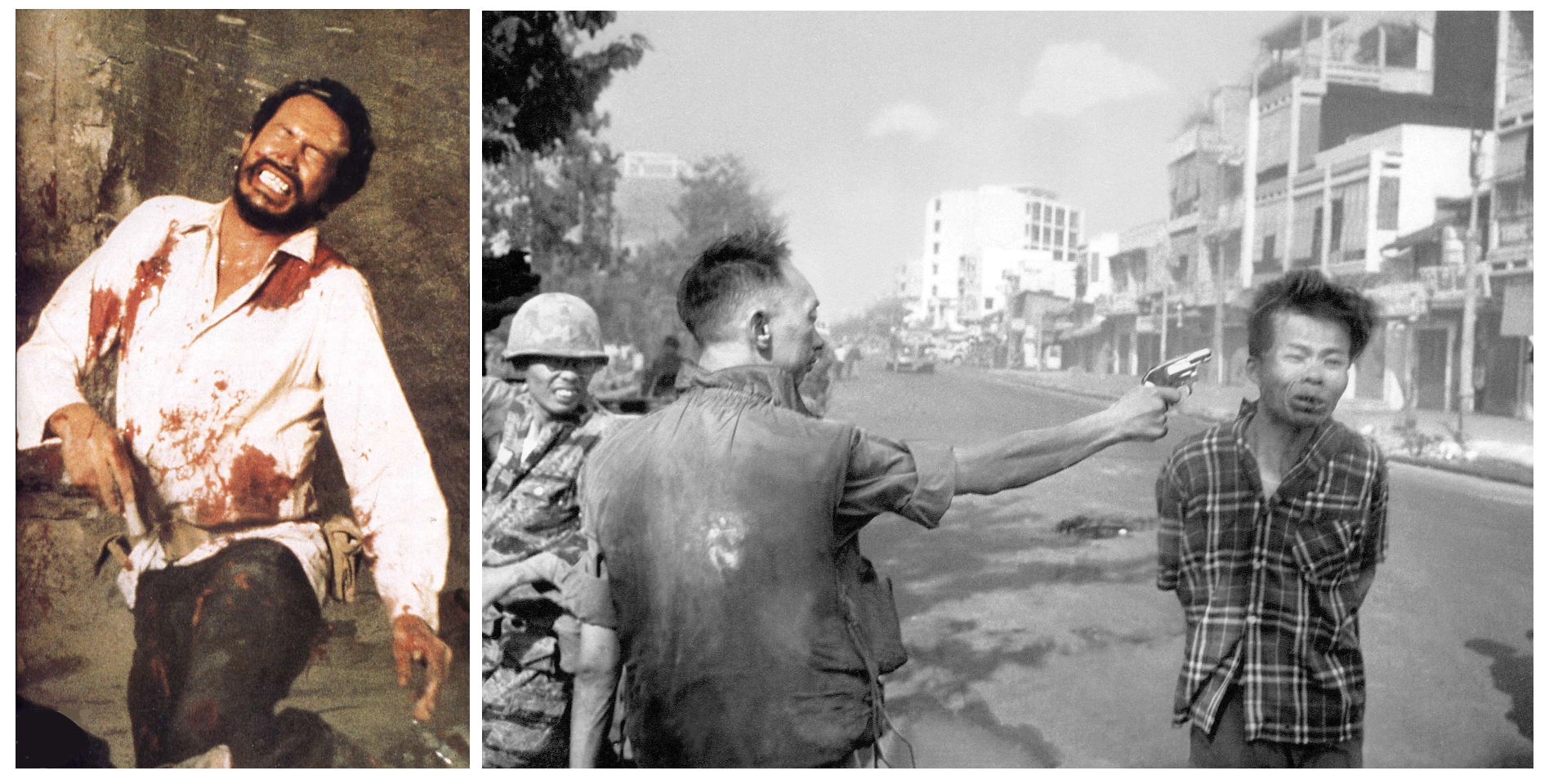

This lent an attraction to the ones I’d otherwise be least interested in; cowboys and army-men were the most ubiquitous and least differentiated of plastic toys back then, but Marx’s included figures like the unforgettable gunshot victim (duel loser? cornered horsethief? prey for bandits? Who would ever know?) with his face contorted, his body twisted, and the gunshot blowing out of his back. This was a favorite theme of the company, echoed in wounded soldiers, arrowed frontiersmen, rubbed-out gangsters and even dead horses (though often the protruding projectiles or fallen hats and helmets disappear from the figures in decades of wear-and-tear, missing evidence of perfect crimes).

There are relatively few specimens of such grotesquerie in the orthodox sculptural canon, or at least, few enough that they stand out and are (admittedly) studied extensively as anomalies: the writhing Laocoön and His Sons, the nasty Boy Strangling a Goose, and, for that sense of personalized anguish that Marx examined so closely, Philip the Arab, the nervous, queasy, apparently official portrait of a Roman emperor who had entered the position through assassination and was soon to leave the same way. (He bears, of course, a racist appellation, which reminds us that the “forms” are prescriptions; not ideals perceived by particularly sensitive philosophical observers, but labels applied by them to what they felt was essential.)

One quality that isn’t inscribed in Marx’s effigies is heroism or villainy; there is the history-buff’s and war-reenactor’s sheer connoisseurship of conflict in these scenarios, and they show no particular glamorizing of the designated “good guys” nor demonization/caricaturing of the “bad.” A pairing of “Pioneer” and “Indian” figures, found at random in a flea market and linked on my shelf — in the classic spirit of recombination that kids when the toys were being produced would have exercised by default due to incomplete and unpredictable availability of individual pieces — display expressions of equal and opposite ferocity, a Platonic couplet of American territorial animus. (The fact that there is no framing of one as colonizer and one as defender of that territory does impose an ahistorical moral equivalency that is itself an editorial spin, but the attitudes of Empire’s traditional opponents and even America’s official wartime enemies are carved with sufficient realism and dignity that each is identifiable as the hero of their own context, and could easily be played that way by any kid… as long as such a role was conceivable, which of course the Platonic program seeks to foreclose.)

As locked into the textbook specifics of given time periods as they might be, these figures were still carved with the sensibilities of the times they were made in. It’s partially that, as far as I can tell from online collector cataloging and the date-stamps Marx pressed into the base of each larger figure (yes, this company maker’s-marked all its creations, pun intended?), the playsets enjoyed a heyday in the mid-1950s and the standalone figures had theirs in the mid-’60s-to-mid-’70s. The former period was the last time America conceived of anything close to a national consensus, expressed in the playsets’ collective activity; for the following decade or more, rugged individuality, disillusioned isolation, and lone vigilantism were mass culture’s defining points of view.

But also, it’s hard to imagine artifacts like this (especially the larger figures) being created before photojournalism’s ability to monumentalize the moment and solidify the immediate. The tradition of “history painting” sought to capture the roiling chaos of bodies in motion and conflict, but mainly to the ends of dynamic composition and overall crowd-scene melodrama. It was a quintessentially external experience of battle (and other milestone human events). The earliest photography sought to make statues of public personages and iconic civilian types; stationary, stage-managed, and centered on surface appearance.

Photojournalism focused in on subjective individual experience; while freezing the in-motion moment, it also visualized the internal. While midcentury cinema was restoring a level of violent realism to our previously-filtered national narratives of Westerns, war and gangland crime, perhaps even refreshing them for audiences lulled by generic entertainment, journalism was looming in the public consciousness with images of the type of incidents no one builds monuments to. A culture conditioned by Sam Peckinpah Westerns and saturated by the Vietcong soldier’s summary execution is one in which the Shot Cowboy makes its way into toyboxes.

Sanitizing kids’ content is enough of a recurrent program in American society that the truthfulness of these disturbing playthings remains a shock to those who come across them years later. The lesson of the space between these dead soldiers and Grand Theft Auto is that we were never innocent. Though it’s possible that we never know what we’re seeing at the time.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE