OFF-TOPIC (45)

By:

November 9, 2022

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For a supernatural time of year and a chilly season of rising supremacy, we convene a council of experts on golems, both legendary and current, in graven images, enchanted writings and words brought to life on stages and screens…

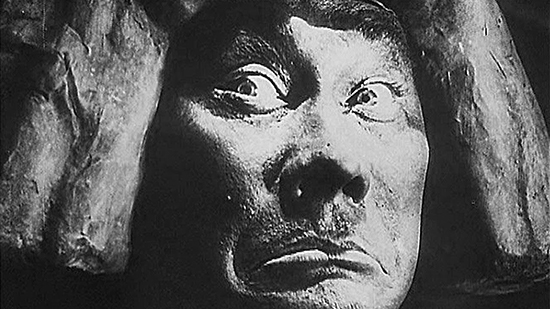

It’s the Golem’s absence that makes him feel real. Out of reach in popular reference for decades at a time, just as he rises after centuries in his own lore, the Golem requires excavation, and rewards mystery. Only things that really exist call for this level of secrecy. You have to search for mass-culture Golems in a sea of vampires and zombies; the folklore is not a household story, even in Jewish households — I don’t think I’d ever heard of the Golem ’til I was flipping through some early-’70s book of my brother’s — “The Silent Cinema”? — and was stared down by Paul Wegener’s furious face, in frame-filling closeup, from one of his German-made Golem movies in the 1910s and ’20s. I would creep into a room, open the book to that image, slam it in terror and run away, to repeat regularly. Even from the page, the Golem felt like a living, raging force, frightening and fascinating; other, more static images from the movie seemed like mementos smuggled in from a parallel universe, the forgotten franchise of a readymade mythic superhero, Wegener’s martial tunic and concrete Dutchboy ’do as iconic as Karloff’s flattop Frankenstein or Lugosi’s cape.

Too Jewish (as Hollywood might say), Too Strong. I would learn that unlike Shelley’s and Stoker’s monsters, the Golem was based on a story people actually believed (the sculpted giant a mystic Rabbi breathed life into, to fight back against pogroms in Medieval Prague before going out of control); I didn’t yet get that the society which had produced Wegener’s Der Golem had ceased to exist, and the culture that created the Golem had nearly been wiped out, in the ensuing years. But somehow, even as an 8-year-old I sensed the cultural specificity and loaded politics of the character and concept; from my mom’s stories of daily beatdowns of her brother and slurrings of her by antisemites in old Chicago, I knew that the Jews could use a Golem.

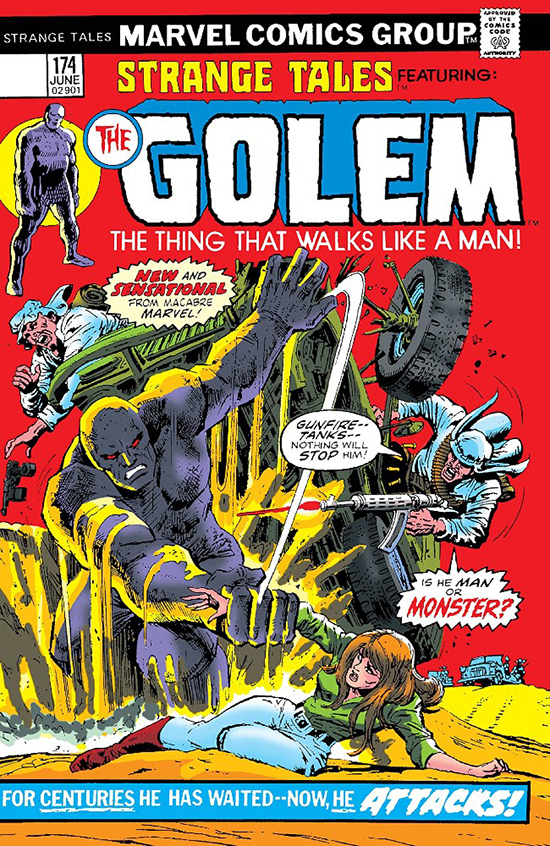

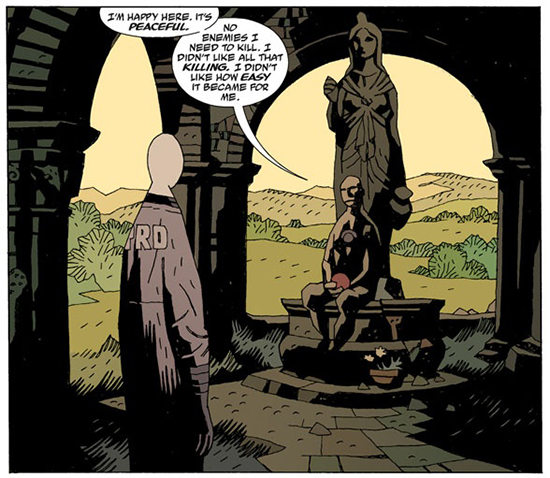

He did come back, sans Dutchboy or any real distinguishing features, as a Marvel comic for a few months in 1974, and even then, it seemed, mostly because they were running out of categories for an already-waning monster-comics craze, and had run out of ideas even sooner, pitting their nondescript stone man against vaguely Talmudic demons and stereotypical Arab terrorists for three lackluster issues (which came out sporadically and ended with an uncommon letter of apology from the editorial team). After that, headlining golems were hard to come by, and so were golems even as supporting players, the most memorable perhaps being Roger the Homunculus from Mike Mignola’s Hellboy/B.P.R.D. comics, a gentle soul and fierce protector seeking to mold his own purpose while fitting into his chosen misfit family of fantastic creatures.

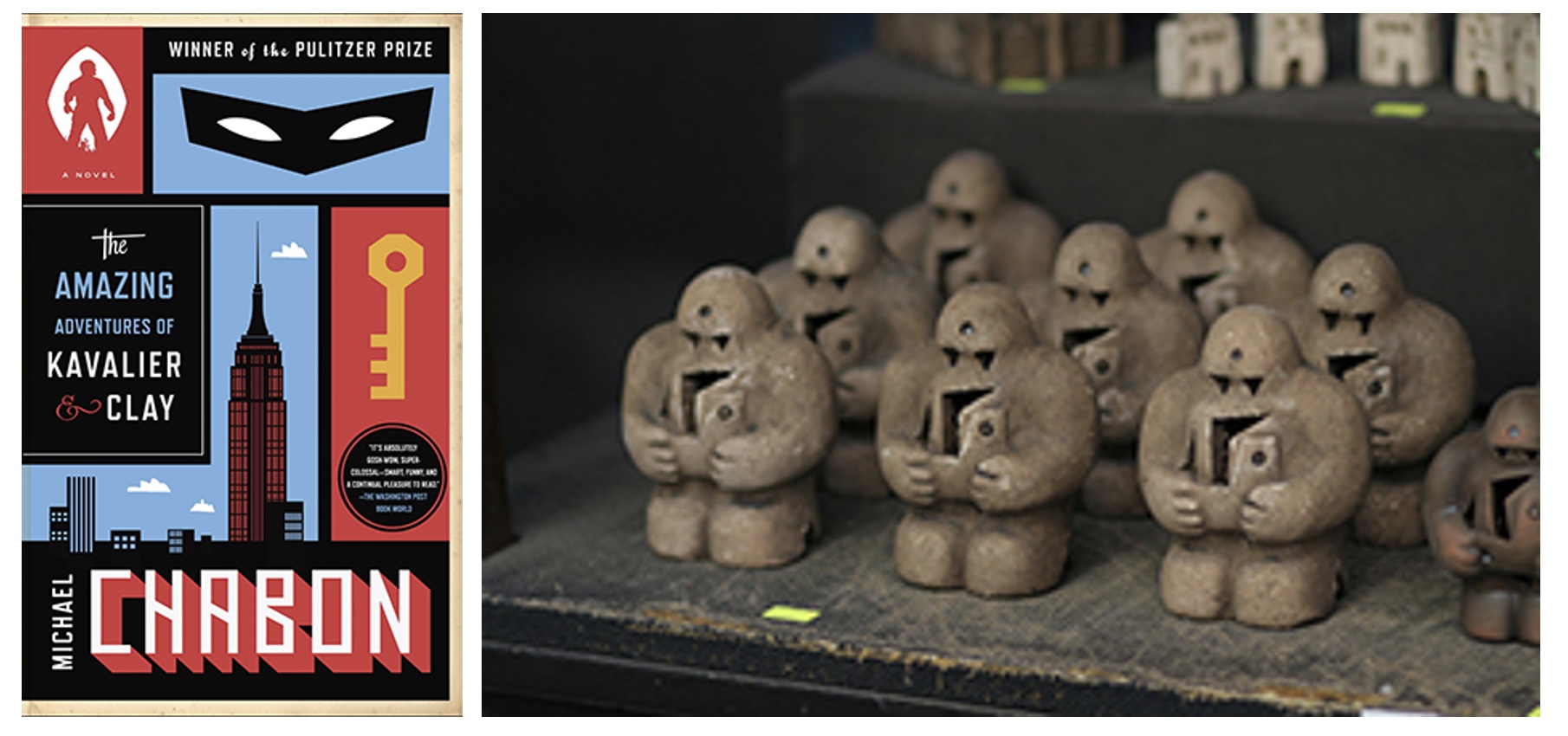

Even the most famous comicbook Golem is a fiction within a fiction, the comic only existing as an unpublished masterwork of Joe Kavalier described in Michael Chabon’s prose novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, in which the “historical” Golem itself is a magic-realist motif, supposedly smuggled out of Nazi-era Prague with refugee Joe and showing up as a crate of dust on his doorstep years later. I started reading that book while on a trip to Prague in 2003, delighting in the one place on Earth where the Golem’s story is common currency and figurines of him are as plentiful as Statue of Liberty souvenirs in NYC.

Back home it was a long wait after Chabon’s novel, but the 2010s and ’20s have been well-trod ground for golems. The comeback of ethnic cleansing and grassroots uprising, the moral choices competing with survival crises, the cautionary power-fables of popular franchises from LOTR to the MCU, all suggest that the Golem’s time is one we’re once more living in.

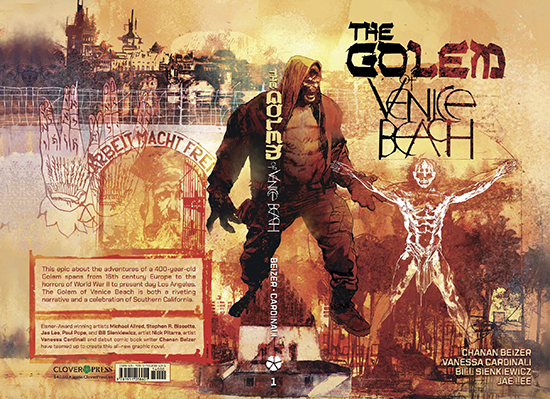

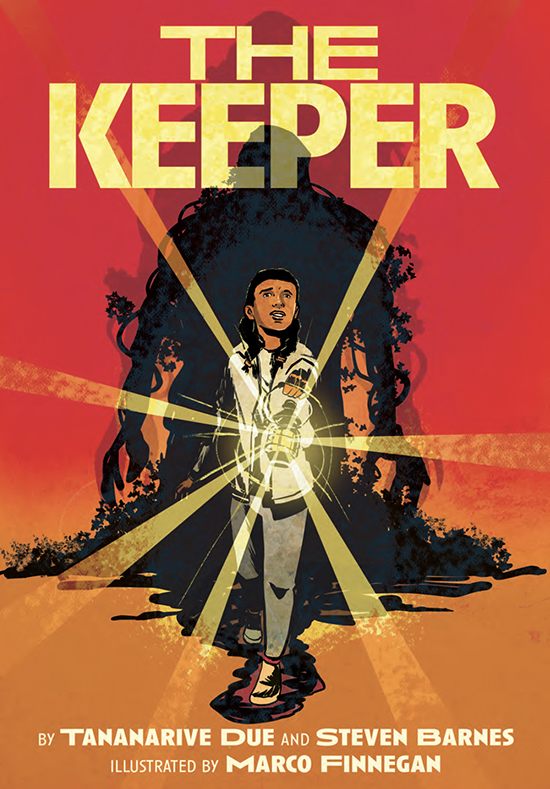

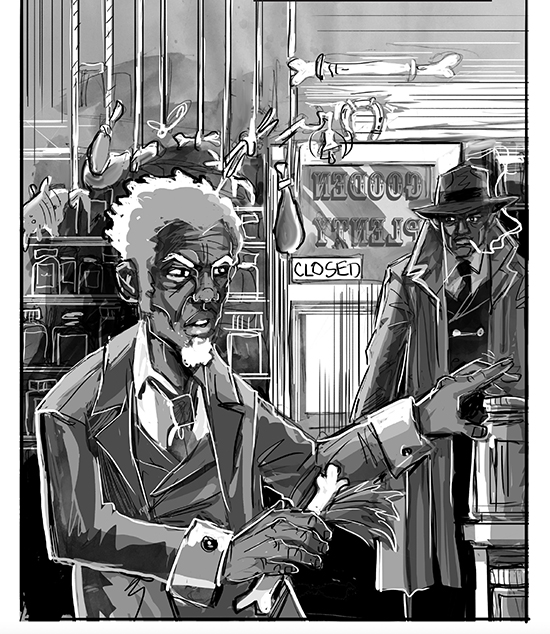

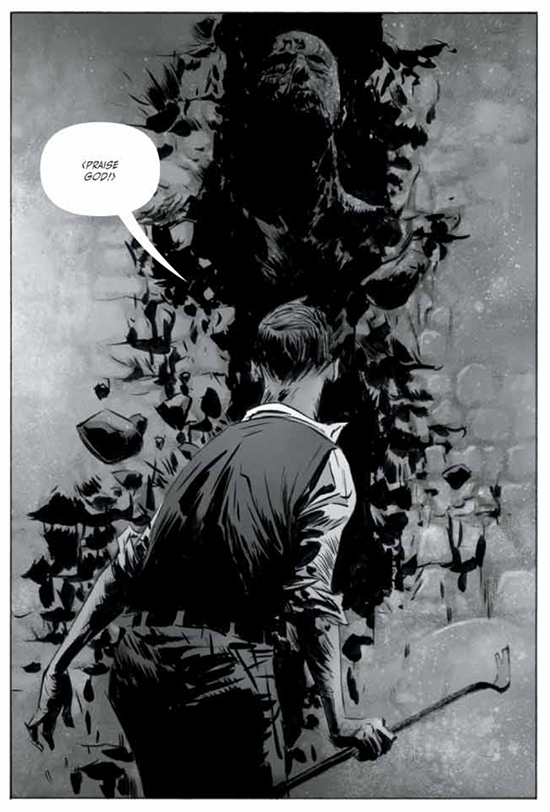

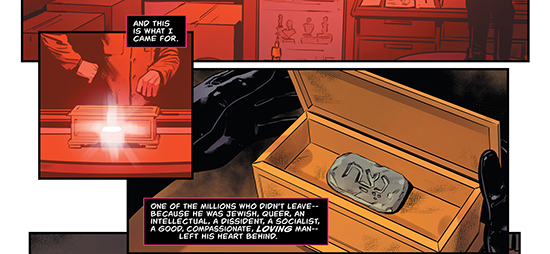

I gathered some of my favorite golem scholars to discourse on what the myth means today. Edward Einhorn’s play Golem Stories is an emotional verité retelling of the original medieval tale, in which we see the consequences of the Golem, aka Joseph, not just developing a mind of his own but possessing a soul of his own that is hard for his creator’s household to acknowledge. Chanan Beizer & Vanessa Cardinali’s new graphic novel, The Golem of Venice Beach, revives the Golem (here called Adam) into a modern world as an often-unwanted protector of people who in many cases have inflicted their own problems. Tananarive Due, Steven Barnes and Marco Finnegan’s recent graphic novel The Keeper follows an orphaned girl whose inherited guardian may be what’s keeping her from a more sheltering, unsolitary community. Helene Wecker’s prose novel The Golem and the Jinni pairs a rare female golem, Chava, with a reawakened jinni, Ahmad, each technically free from now-dead masters but each facing the promise and terror of joining humanity, amidst the enchanting and fearsome ferment of early-1900s immigrant New York City, a time and place almost as legendary to us as they are. John Jennings’ graphic novel Blue Hand Mojo: Hard Times Road features a home-made golem in Depression-era Chicago, created to take vengeance on oppressive gangsters, animated by a mother’s grief, but sustained by the togetherness that truly gives life. Andrew Wheeler and Travis Moore’s comic series Sins of the Black Flamingo’s first arc centers on a glamorous thief who specializes in heisting (or stealing back) occult artifacts, one of which turns out to be a family golem, Abel, housing a mortal spirit placed there by his gay lover to live beyond their deaths in Nazi Germany, and awakened to a world with new possibilities and many of the same prejudices, a special being still in search of a unique self.

I spoke with Einhorn, Beizer, Due, Barnes, Wecker, Jennings and Wheeler, as well as The Golem of Venice Beach editor Chris Stevens and iconic horror artist Stephen Bissette (also a contributor to Venice Beach), to discuss what draws them to these stories, and what conditions call out a golem.

HILOBROW: The Golem is as close as you can get to saying a character is a “walking metaphor” without exaggeration; he or she is literally brought to life by a written word. The Golem as a character becomes a vessel for any number of metaphors, both medieval and modern. It’s only more recently, I think, that we’ve even conceived of the Golem’s subjectivity, as we see in several or your works. What does the Golem “mean,” and is it a specifically modern idea for them to have thoughts and agency of their own?

BARNES: If you look at the Golem as specific to Jewish mythology, then you can confine it there. If on the other hand golems existed, they would not be specific to Jewish mythology, that would be one doorway in on a concept or creature called a golem by them, and other names in other cultures.

EINHORN: The early accounts, some would make the Golem sound more mechanical in nature, but there are even glimmerings then of using the spirit of someone who had died to help animate the Golem; that appears in a lot of the early mythology as well. And once you get into the idea that you have the spirit of somebody who once lived that helps animate this creature, it goes hand-in-hand with thinking there might be some other sort of agency, some sort of consciousness that exists within the creature as well.

DUE: In The Keeper the creature is very much like a golem; I can see now in retrospect [laughs], but it was not conceived that way consciously. I do find some interesting overlap in this notion of the creature appearing as a protector of a community. That’s very much what this creature is, the community being this family, but also previous generations of the family. In the sense of how we created this creature, it’s also almost like a wish-fulfillment. If only there were a creature that could be created from inanimate objects, or…

BARNES: I tend to look at the creature more like a jinni. A thing that has a life of its own, but is bound to protect — perhaps by a spell; we don’t know that much about its history — but there is that question of, was it created by the act of shaping something out of clay and writing the name of god on it…or was it summoned by that? Clearly it’s possible to look at it multiple ways.

WECKER: I was reading The Keeper within the context of this get-together, and I was thinking, “This is absolutely a golem,” and I was waiting for the word “golem” to pop up [laughs], and I got to the end and I was like, okay, no, it isn’t, but there is, like you said, so much overlap in the ideas of generational protection, and community, and righting a wrong, and helping someone powerless — and, the thing then turning against the wishes of the person who animates it. Like Steven said earlier, there was this specifically Jewish way of looking at it, and then there is the whole larger spectrum of, okay: This is a creature that is the Frankenstein tale, it is any number of cyborgs, or Asimovian robots getting out of control. It’s like, we exist in the present and if you look into the past the Golem is fantasy, and if you look into the future the Golem is sci-fi. So there is this world of creatures that can be conceived of as golems; the original story has Jewish particulars, but… I see golems everywhere now!

BEIZER: For me, what I always thought of, is that it really [expresses] the idea of the law of unintended consequences. Creating a creature to protect, and as Helene just said it becomes violent, you can’t control it; it’s the way humanity creates something in its own image, let’s say, but you can’t control that eventually. And it’s very adaptable. In The Keeper it’s more of a horror genre, in Edward’s play it’s more of a morality issue, in Helene’s [book], it’s almost a love story, of two different types of creatures. So it’s very adaptable, but in my mind it always comes back to the law of unintended consequences; you never know what you’re gonna get, when you create a golem.

BISSETTE: Well, all of it’s a metaphor for parenting, really. [laughter] None of us know what the unintended consequences are until you have a kid.

HILOBROW: Significant you should say that, Steve, since one thing I noticed about several of the stories is that the golem, these days, can seem like a generational burden — even though the old myths are cautionary, they have this idea of the Golem as something that will be called forth again like Excalibur popping back out of the lake when we need it most; whereas now, it’s almost more of a curse. Definitely in The Keeper and The Golem of Venice Beach, and maybe with the inherited golem in your comic, Andrew?

WHEELER: In my comic book, the golem is very much a queer interpretation. So it represents survival and endurance, and it’s the golem as the protector of one individual, one soul placed in [its] body. So [I’m] sort of using the Golem in the modern day as a representation of our endurance in the face of oppression, in the face of the forces of destruction that have returned to the world. But it’s also a way to explore the idea of the baby gay — the character Abel is sort of the young naive gay character whose malleability gives them a way of surviving. So that, to me, was the reason to make that character a golem: they endure, but they endure because of their elasticity.

HILOBROW: I had noticed that some of the more modern interpretations do link the malleability of the clay with a more modern, almost science-fictional concept of fluidity, a Plastic-Man type of conception. Which we see with Helene’s golem poking needles into her skin and seeing if she can feel pain, and in the way that Abel can be shot with bullets and then kind of snap back. Steve (Bissette), have you ever tackled a golem? Not that I can think of, even though there are so many monsters you’ve interpreted, but what are your thoughts on how those themes would be expressed visually?

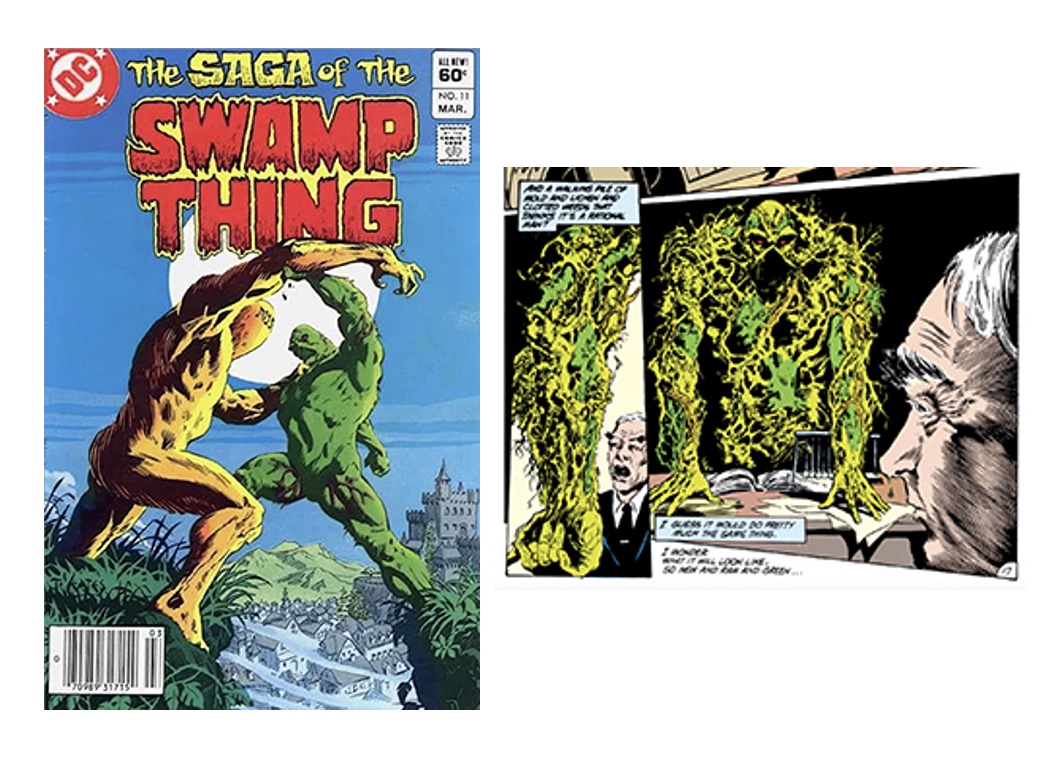

BISSETTE: Actually — my name’s not on it, but I ghost-laid out Saga of the Swamp Thing number 13, which was the issue where writer Marty Pasko and artist Tom Yeates had… the Golem, as the guest-monster. So…I did a golem, for four-color comics! The representation of the Golem, for my generation, was really fixed by growing up with magazines like Famous Monsters of Filmland, and you would see that photograph of Paul Wegener, the German actor — I think he actually ended up doing three films spinning off of the Golem legend. That really became cemented into my consciousness and my unconsciousness as the 20th Century incarnation of the Golem.

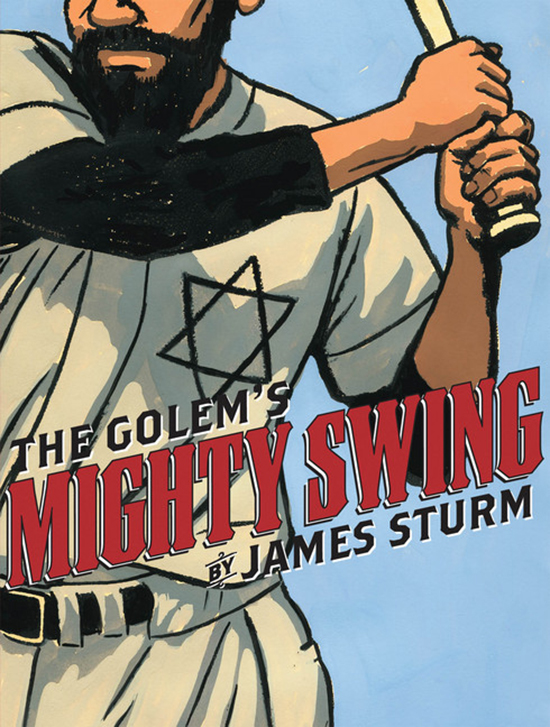

Although, growing up… my friend James Sturm did the graphic novel The Golem’s Mighty Swing, involving a Jewish ball team and an African American ball player who gets to play on the team by being disguised as the Golem. I also think of the novel Kavalier and Clay which, particularly during the first five years of my teaching at the Center for Cartoon Studies, every student there knew that novel, had read that novel. It’s not that I would see what was going on through the filter of my students, but incarnations of the Golem that popped up on programs like The X Files tended to be the image that my students would have in their head as, oh, that’s what a golem is. So I think generationally, it’s whatever is in the pop culture that is the current incarnation that tends to really fix into the contemporary public imagination. Although, any creator, once it’s in our hands to interpret, you immediately want to recreate it, to make it your own, or make it different from what you were aware of as being the archetype. And that then becomes the catalyst for the next generation, if your work is seen at all.

JENNINGS: The golem that I have in my story was definitely powered by revenge, and justice, and utilizes a token, some type of object that carries…that can be focused around the energy of this mother whose son was killed. She uses this object of endearment as a central focus. I also did go with the, almost the Batman’s Clayface style, where he actually can become like mud, and he can harden pieces of his body; it’s kind of cartoonish, but also extremely terrifying [laughs], this giant lump of mud. It’s a golem made out of Mississippi mud, definitely trying to jump across those seams.

These days, I’m thinking — y’know, Steve mentioned the golem that was depicted in The X-Files; I think my first intersection with the idea of a golem was probably It! — exclamation point [laughs] — it was a film from 1967 with Roddy McDowell; I didn’t see the original Golem until later, but It! was the one that stuck with me. Of course there’s a new film [The Golem by Doron & Yoav Paz, 2018] that just came out two years ago or so that I thought was pretty — it was like a little child golem who had psychokinetic powers, it was very beautifully violent. And then I was also thinking about the idea of the tulpa, from Tibetan belief structure. This idea of focused energy into inanimate objects that become this living thing. There’s a spectrum of golem-ness. Then of course I think about pop-culture golems, like the Thing from the Fantastic Four, or the Hulk, particularly when you’re looking at Jewish American creators.

BISSETTE: When you bring that up, [DC’s zombie-like] Solomon Grundy comes to mind — or characters like The Heap, and Man-Thing and Swamp Thing; they all become a surrogate incarnation of the Golem archetype. But very different in that none of them have been created to serve a community.

JENNINGS: That’s a good point — though Swamp Thing, maybe in his later incarnations, cause he’s a representative of Nature.

BARNES: If we back up for a moment, we can [ask], what is the Golem an example of, worldwide? You take a look at all the kinds of mythological creatures that have been invented, and you say, okay, the Golem is in this set of the inanimate object that is animated by thought, by emotion, by skill, by magic, and in this particular case this was done to serve a community. I would say the metaphor there is human will and dreams acting upon the inanimate world to create machines, energy, so forth and so on. It’s part of a process that we go through in creation. Turning objects into things that serve us is something that is not uniquely human, but we’ve certainly taken it further than crows do [laughs]. The Golem is an example of something, so it’s important probably not to think that it’s utterly singular, and nothing like that had ever been done anywhere else.

EINHORN: In a lot of ways I think it’s a wish-fulfillment about strength. The original situation is, a Jewish community that felt very helpless. That were the subject of the blood libel, this story that was going around; and so there was this idea, there was a wish-fulfillment about having strength; what if we had the strength to destroy this all. But simultaneously it’s skeptical of that strength, because the strength it theorizes is one that defeats itself in the end. You would think there would be a pure wish-fulfillment, but the answer is that this is not the answer — that this thing that we long for is actually not the answer to our troubles. That’s an interesting paradox.

With my [play] I try to look at the way, all these stories, what are they saying to the society that they’re in, and how [do] they shape them for good or for bad. Because we’re starting the story with, the Jews were almost mythological to the people who were talking about them, thinking of them as these blood-consuming creatures, like vampires to the Christian community that are attacking them. So they’re seen in this monstrous way, and they create this fantasy of another monster, but they negate that monster. And there’s a distrust in that story that I try to play with in my version. Because I do think there’s a worry about whether that story is going to become too powerful for us.

BEIZER: What I enjoyed in Edward’s play so much was that — in my book, the Maharal, [the Rabbi] Judah Lowe ben Bezalel, is almost a mythological figure himself, while in Edward’s story, he doesn’t come across that great, he doesn’t come across that noble. It’s really the Golem that turns it around, the question of, “Are you my friend, are you going to support me or throw me under the bus”; he took the story that the Maharal gave as an example of loyalty, and turned it around on the Maharal, and the Maharal failed that test of loyalty.

HILOBROW: It makes me wonder if the Golem is a cautionary parable, an indictment of human nature overall. We see this recurring motif of the clay of the Golem being this tabula rasa for the will of others, but on the other hand it seems like this more pure state of nature, that could become something beautiful if not for the commands it gets from humans.

STEVENS: It’s fascinating, because being Jewish myself, and knowing of the Golem since I was a little kid, my view of it is very stripped down: That it’s very Jewish; it’s like, “It’s not gonna work out, guys.” [laughter] You go through the Old Testament, none of them…y’know, you grow up and King David is this luminous figure, he wrote the psalms and, beautiful guy in his statue and all that, but if you actually read it David displeases the Lord over and over again; nothing ever quite works out, it’s always a one-step-forward, two-steps-back kind of thing for the Jewish people. Even as everyone [here] seems to agree about wish-fulfillment, I see the Golem as almost the antithesis of a wish-fulfillment, where the Jews couldn’t even be — they couldn’t even have that in their myth, to have it work out for them. They were self-aware, the same way I think, over and over, they knew ultimately they would disappoint the Lord and have to keep striving for it. So maybe my view of the Golem is more depressing.

WECKER: Oh, it’s both at the same time; it’s a desire for power, and at the same time an absolute distrust of power. “If only we could fight our enemies,” and at the same time, seeing violence turned on your own community so often, having a moral framework that knows that power is corruptive, what are you gonna do with this thing after[ward]. Going back to what we were saying before about the generational burden of the Golem, it’s a weapon, you can’t just — are you gonna have this thing in the attic for the rest of existence? It’s gonna wake up at some point, it’s gonna be an issue, it will be like a nuclear arms race. That doesn’t mean you don’t want the weapon, in order to survive. So it’s that paradox.

In fact, the next book that I’m writing, it’s Book 3 in the series, there is that theme to it as well. We’re dealing with a number of years on, and you look at a creature that could be functionally immortal, and that’s just out there in the world. Well, that’s a bomb waiting to go off, what do you do?

BARNES: I would think that stories don’t start with “this means this, and this means that.” Stories mostly start with people wanting to tell a good tale based upon things that they’ve experienced, or things that they dream of. If a story lasts, if it persists, it’s because the people who hear the story find meaning in it. You can analyze that, but the idea that sometimes comes up in critical conversations that implies that stories start with a meaning, is missing what the creative process actually is. Thousands of stories get told every day; the stories that survive fit some need that we have, to make sense of our world, and to believe that it is possible for us to act with joy.

EINHORN: I think that stories express our subconscious in a lot of ways. We may not start with this-means-this-and-this-means-that, but buried inside the story that we’re choosing to tell, there are all sorts of meanings that are usually a little bit subconscious, and then when they resonate with other people, it means that same process may be going on with someone else. We tease out the meanings of things, and become conscious of those meanings, but often I think they’re there from the very beginning, it’s just [about] asking what is going on in that story, what is it actually saying.

HILOBROW: And there are non-“universal” ingredients to the narrative recipe that can affect the meaning too. It’s definitely striking that in your book, Helene, there is a female golem, which we don’t see a lot; in The Keeper we have A Girl and Her Golem, which we also don’t see often, it’s usually a male authority figure; and even your golem, Andrew, could be argued to have a certain maternal aspect (for those who haven’t read it, there’s a scene where a character is revitalized by taking this mudbath that he doesn’t realize is the golem, converted to this lifegiving substance). Helene, is a female golem more capable of independent thought? That is, how endemic to the golem are the elements which we would tend to conflate with maleness; the protector, the champion, the literally closed-in emotions…

WECKER: I don’t know, all the comicbook writers and artists here are making me wish I was doing a more visual medium, because I feel in some ways I cheated a little with Chava, my golem, in that her whole reason that she was created was to be someone’s wife, and therefore she has to pass as human. With that one decision there’s a lot that gets loaded into it, where she isn’t hiding out in the shadows, she is a woman walking through a city in broad daylight. So it becomes more of a, “how do I behave normally, how do I learn to be the person that everyone thinks I am, and what dangers are there if I misstep.” She’s a very nontraditional golem in that way, in that she talks — I think a number of our golems talk at least somewhat — and she’s got a pretty developed mind but at the same time she has a certain simplicity of personality. So, that puts her in positions where she has to think more, as far as her own capabilities will allow her, because she has to be clever enough to evade detection.

There was a lot I only realized later on that I was burdening her with, as a female golem that was going to exist in turn-of-the-20th-Century Manhattan, and here is this incredibly strong figure with a capacity for total violence, living in a time where women are expected to be very frail and immobile, and what sort of constraints is that going to place on her. In my second book [The Hidden Palace] I created a golem that was a little more traditional, his name is Yossele and I was able to do more of the hulking-clay-dude-in-the-basement with him, and that was both liberating on the one hand, and totally constraining in another way. So, I’ve come at it from both ends of the golem spectrum.

BEIZER: I found it very interesting how your golem had a job in a bakery and was very good at it, learned interpersonal skills…my golem does not get a job, he lives a very lonely existence. But he does pass as human. So in my way of thinking about it, my golem is a creature out of time, it was created 400 years ago, and it’s still walking around in the 21st Century; it longs for oblivion, it was not meant to walk the Earth forever. So it does have its own mind, he does have his own mind, and he does have his own wish-fulfillment for himself, which is basically to not exist. A creature out of time trying to find a place in a world that he was not meant to exist in. While in yours Helene, I definitely feel that Chava can function and continue to function in the world that you’ve created, so I found that very very interesting and unique.

WECKER: I liked Adam so much, I loved your golem! I love that he loves palindromes, it’s just the sweetest thing, he’s just got that little bit of cleverness about him, and he likes whimsy — and the dichotomy of that, having that sadly whimsical personality in this hulking, hulking body, that is drawn so evocatively, he’s like four times the size of everyone else around him, it was just great to read.

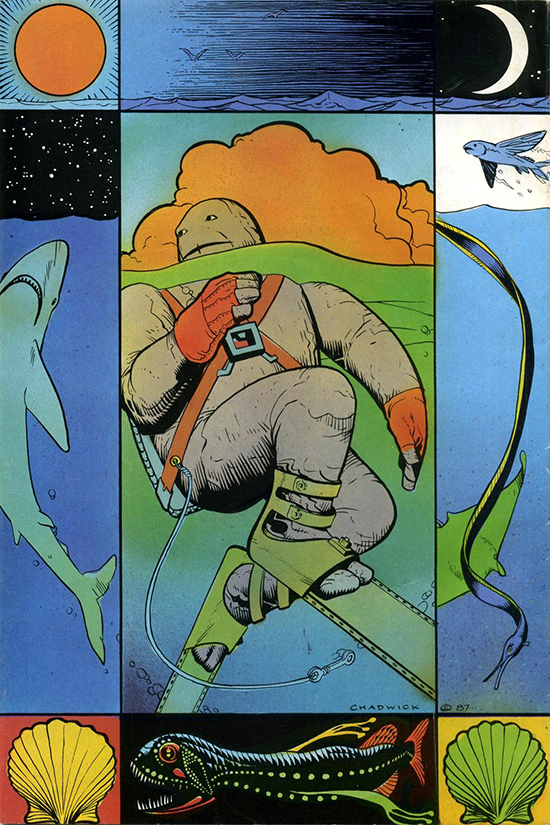

JENNINGS: I just thought of another comicbook golem: Paul Chadwick’s Concrete.

BEIZER: I was so influenced by Concrete!

STEVENS: Everybody lets out a cheer. [laughs]

BEIZER: There was a scene in one of the Concrete books where Concrete walks on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. And that so impressed on me, “of course it makes sense, he doesn’t need to breathe, he’s not affected by it”… that I tried to capture just a moment of that in my own book.

WECKER: It’s like the Harryhausen image, of walking along… which movie is it where they’re walking along the bottom of the…?

BARNES: Mysterious Island!

WECKER: I did the same thing in The Golem and the Jinni, because, once you’ve got that, how do you not use it?! You’ve got to have a little bit of it just to put that stamp on it.

HILOBROW: I was going to ask what the common root of those subaquatic walks was!

BARNES: Think about Harryhausen as having brought inanimate objects to life. Breathing his art, and his will, and his emotion — I had the great pleasure of having him on my radio show years ago, and I can just tell you that this was an artist of the highest level, just a man who — aren’t we all, as artists, trying to take inanimate objects, even if it’s only splashes of ink on a page, and make them move — either themselves, or the emotions of those who interpret them. If that isn’t a metaphor for the primary thing we’re trying to do I don’t know what is.

HILOBROW: It’s funny that we mention all these nautical associations, cuz I was wondering if anyone here saw the recent series version of The Man Who Fell to Earth?

[No one had yet]

HILOBROW: —I was curious if anyone had a take on the figure of Faraday, the main character, as a golem, since he’s a vessel in many ways — he’s trying to get water back to his home planet, and he himself is this alien who’s encased in this construct of skin…

JENNINGS: I haven’t seen it but I would hazard to say that the Black body, or Black folk, could be considered golems. I always think about Blackness as a construct; as, again, an extension of hopes and fears that certain white people pour those things into. The stereotype itself is a golem. The Black subject is always trying to get out of that construct.

WECKER: The servant that you create, that you’re afraid of?

JENNINGS: Right.

EINHORN: That’s one of the things I was trying to get at with my play; that the Maharal had created a construct and then the actual creature did not fit the construct that he thought he had created, and he refused to recognize anything except the construct that he wanted it to be.

HILOBROW: In this talk about constructs, it makes me wonder even further about ideas of…“authenticity” is a loaded word, but, rootedness: the way that Chava finds herself revitalized when she comes in contact with the earth and when she’s in Central Park, and how your golem, John, is made from Mississippi mud; and it seems that the “golem” in The Keeper also has that feeling of being gathered from the earth. What does this say about the character of the creature…or feelings of association with the golem?

JENNINGS: I was thinking about my golem, Red, as an extension of conjuring practices, and certain Hoodoo practices, where what they call goofer dust is used, which is a mixture of substances, and the main ingredient is graveyard dust. People who practice conjure work think of the body as containing a lot of energy, and when you die the energy is released slowly back to the soil. That’s why they would use the graveyard dust. So I thought what would be particular about the golem because of different kinds of energy that would be released in the state of Mississippi —I’m from Mississippi too, by the way — what types of energies live in the earth, in the ground, and how could they be harnessed for this creature. So it was using different kinds of arcane practices around what would be called conjure or witchcraft of what-have-you [laughs], the hodgepodge of — that’s what Hoodoo is, a hodgepodge of different types of practices, because it started in New Orleans and then kind of creeps up the Appalachian mountains.

HILOBROW: On the one hand, the Golem seems a concept especially suited to genre fiction — he’s basically a medieval superhero — but on the other hand, the Golem is relatively scarce in pop culture. What are your thoughts on why we don’t see more of them, and whether you found your golem characters particularly suited to an adventure, a romance, a horror story?

BARNES: I think you see a lot of characters, or creatures, that fit into the same category the golem fits into. The important thing is to broaden the view; when you back up a level of abstraction you’ll see lots of ’em.

WHEELER: One of the things I was wondering is, are people nervous to write about golems if they’re not Jewish. That was a real concern for me, and I assume other non-Jewish authors — not that authors are always the most sensitive people — as Steven was saying, it’s a more universal concept than it seems to be on first blush, but it also has a strong cultural and faith-based element that can make people feel nervous about whether or not they’re going to do it justice.

WECKER: There’s a specificity to the Jewish creation that is called the Golem that brings baggage with it. Cultural baggage, historical baggage, whatever. In that sense it is weird to me when I see golems that are called “golems” that aren’t Jewish. Now, that is my point of view as a creator, and as a Jewish writer, and I wonder — it was asked, where are the modern manifestations of golems; when I try to do golem research, these days it’s all video games that come back to me. The Iron Golem, or the Coal Golem, or whatever game it is, these are the grunts that walk around and do your bidding. And it’s like “okay, I see that, that’s interesting,” but at the same time it’s like, has the word “golem” become divorced from the Jewish myth. It’s not for me to say whether that’s “good” or “bad,” in the way that all of this stuff becomes universalized at some point — but I also have seen creations that are called golems and are divorced from Judaism when it’s very clearly the Jewish golem story; that irks me just a little bit and I could not quite articulate why.

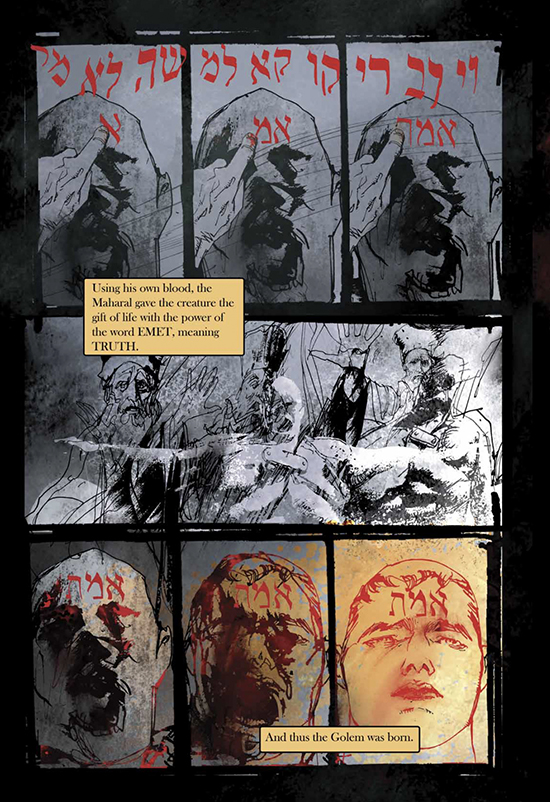

EINHORN: I would agree with the earlier statement that there are a lot of golem-category things, like Frankenstein or…robots, in general. They follow many of the same patterns. One of the patterns that we haven’t even talked about is how the Golem was animated by truth, specifically [the word “emeth” carved into its head]; robots are often usually just truth-tellers, almost naïve truth-tellers. But I also agree that when somebody takes a Jewish legend and takes the Jewish out of it, it feels weird to me. Because I do think there is, in the specifics of what makes something a golem, there is so much about the Jewish experience that fed into that. So, in answering the question of why aren’t there more golems, it depends on what you call a golem.

HILOBROW: And a lot of creators take that baggage with them; certainly, Chanan your golem, and Abel in your book Andrew, are completely tied with…Jewish experience in general but very specifically the Holocaust. And also in the story “The Golem” that your blog put me on to, Helene, by Naomi Kritzer…now that I think of it, most of the pop golems I see do indeed maintain that entire context of Jewishness.

BARNES: Just a thought of a story I would love to see: If you interrogate the question, “If there is magic, then why did oppressed peoples not use that magic against their oppressors?”

BEIZER: I actually did that story — I was intrigued by the fact that, during WWII if there were golems, I would use one.

WECKER: I’ve had people ask me if I’m going to write Chava up to the present day. And I’ve said, “nope!” because there’s the Holocaust just sitting there in the middle. And I cannot deal with her and the Holocaust together, that’s just…because anything I would write — okay, either she goes over and saves everyone and I’ve done some giant wish-fulfillment fantasy that does no service to reality or speaking to history, or I have her sitting watching, and I can’t do that. These two do not meet as far as I’m concerned, the idea of my character as I’ve created her and the reality of the Holocaust; they’re orthogonal and I can’t reconcile them in one work.

BEIZER: I kind of had a workaround; even though my Golem was created in the 16th Century and was put in suspended animation, and is resurrected during WWII, again [there is] the idea of being a creature out of time; it was created to fight battles with swords and arrows, it wasn’t created to fight battles with machineguns and artillery, so it would not survive a direct confrontation during WWII time. So I used the concept of, you’ve got this one shot to use the Golem, when nobody knows what’s going on, and this is your only shot to use it, but once you’ve done [that] — the father has him save his son from a concentration camp — once you get him out of there, your job now is to protect that boy; you can’t save everybody, you can’t go up against the Third Reich by yourself.

BARNES: You limit their power, and therefore the scope of the story. That strikes me as being a valid approach, but clearly, this is a, what a touchy issue; how do you do something useful, and respectful, and powerful, and still respect people who are still alive, with numbers tattooed on their arms. I could not write that story.

WECKER: And just the fact of history as it was. You have to make it a much more personal story.

WHEELER: One of my characters has a speech…she’s a witch…and my story is very much about fascism today, it’s about American Christian [Right] fascism, and her speech is about, I’ve got all this power, imagine how much more I could have done, if it weren’t for people like you screwing everything up. The idea that the world could be even worse today if it weren’t for the efforts that people have made to try and stop — there are always people doing good in the world; they can never do enough to make up for the people doing terrible things.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE