OFF-TOPIC (39)

By:

April 29, 2022

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This session, we hold a peaceful talk with one of pop-culture’s most august balladeers of brutality, in search of the common chord the world could sing…

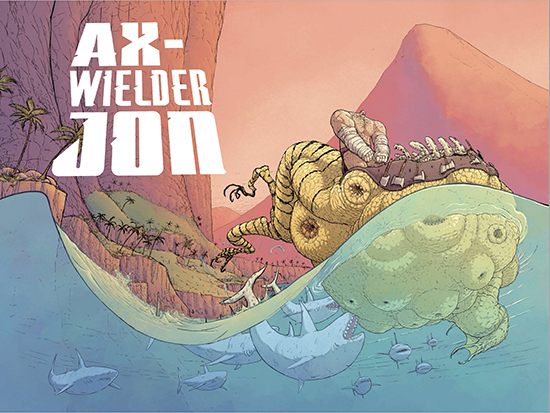

Knowing what to leave out is the most important part of both storytelling and social courtesy — but it takes even longer to learn what’s been left out of ourselves. Missing pieces are strewn all along the path of destruction cut by Ax-Wielder Jon, eponymous protagonist of avant-grindhouse comic artist Nick Pitarra’s debut graphic novel as both author and illustrator.

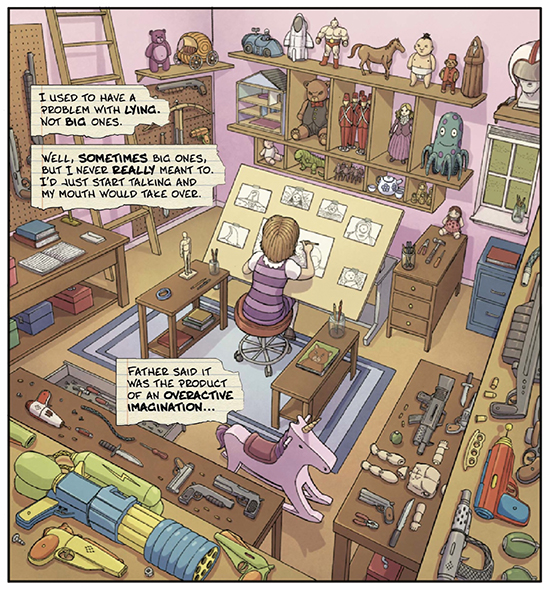

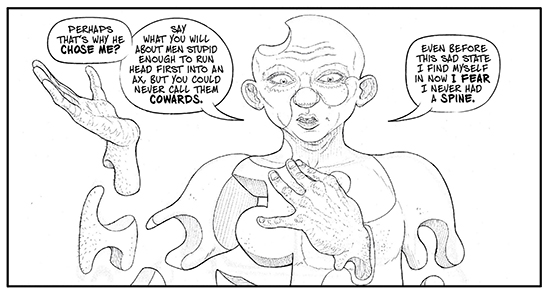

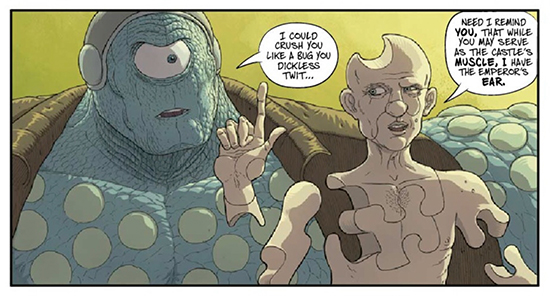

The definitive badass barbarian, there are gaps in his personal history wider than the one cleaved in his face, and we have no idea what the connection is between him and the young girl narrating his story from her drawing-board in some domestic idyll, her own workroom strewn with disassembled and fragmented action-figures and toy weapons. One courtier of the warlord Jon is fighting is literally jigsawed incompletely (one of Pitarra’s most surreal, Oz-like inspirations), and specifically charged with not telling the king’s secrets.

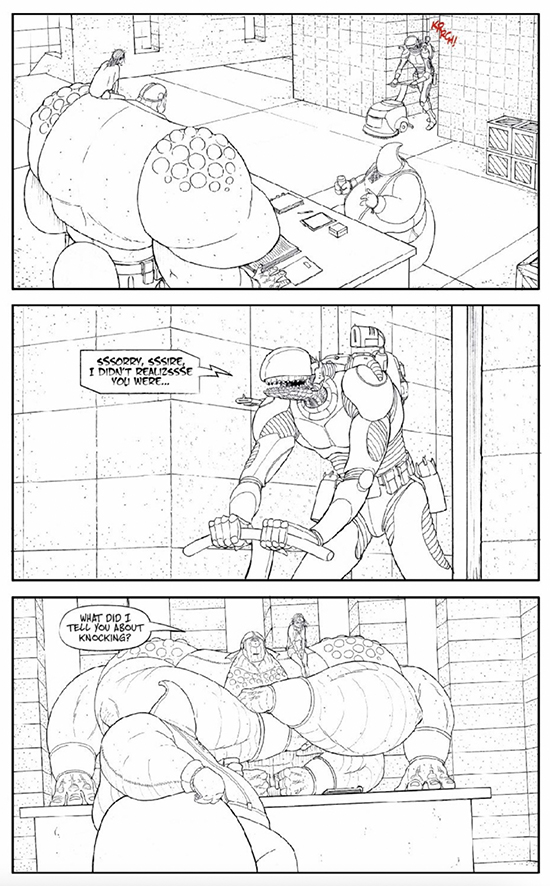

The story itself is stitched seamlessly from Princess Bride-style fairytale, sword & sandal beefcake B-cinema, Game of Thrones intrigue and bloodshed, a Bermuda Triangle of dinosaurs, knights, space-squids and cyborgs, and even dungeon-based dystopian workplace comedy. Our narrator, Basil, may embody the biggest missing piece of Jon, the feminine principle he lacks and which, we discover little by little, he may ironically be hacking his way toward.

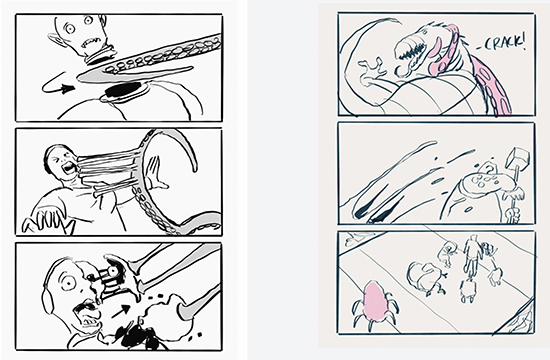

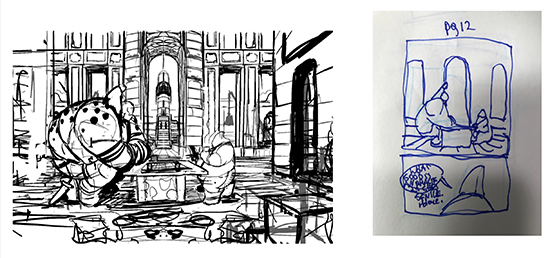

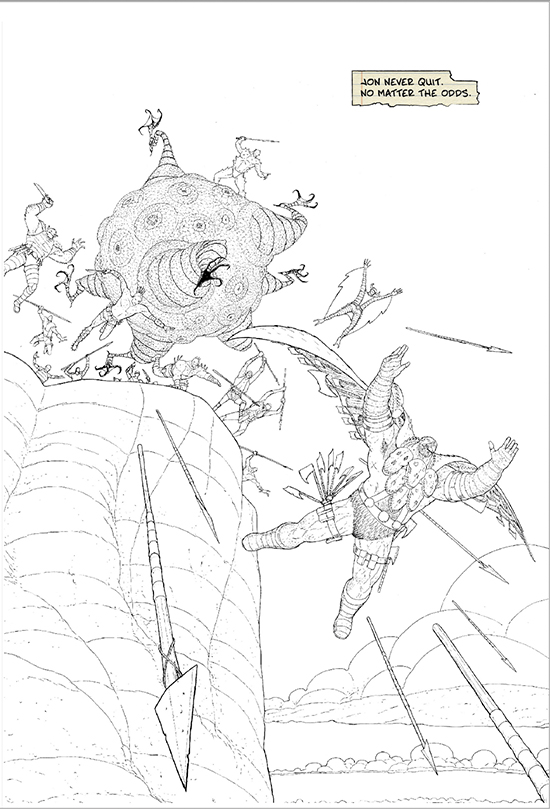

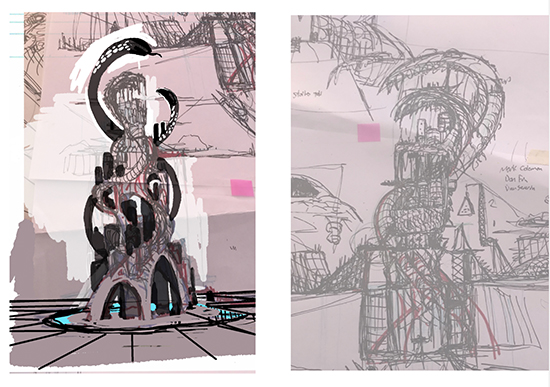

I had the good fortune to see Ax-Wielder Jon as its bones and sinew were coming into place, in a pre-pub work-in-progress that interspersed Pitarra’s layout-sketches with black-and-white linework, pure script copy, and fully rendered setpieces of palace drama, battlefield carnage, and unlikely tender interludes. Pitarra is here doing for brute force what he did for brainpower in his previous best-known work, The Manhattan Projects, co-created with writer Jonathan Hickman and detailing the secret history of global superpowers’ dueling scientific heavyweights, with various evil-twin, alternate-dimension, robot-resurrection versions of Oppenheimer, Einstein et al. even crazier than the ones who merely invented nuclear holocaust.

In that project as in this one, Pitarra’s molecular detail and dynamic compositions, supreme precision and pervasive grunge, set him apart from almost any comic artist and place him closer to a Hieronymus Bosch or the scribe of a medieval illuminated manuscript. On Ax-Wielder Jon he is joined by the otherworldly textures and atmospheres, and hyperreal modeling and moods of colorist Mike Garland, and the expressive typography of one of comics’ most inventive letterers, Ferran Delgado. Acclaimed editor Chris Stevens guides the project, as well as others to come from Pitarra’s new collective self-publishing venture Karoshi Comics (karoshi meaning “to die from overwork in Japanese,” Pitarra offers). It has just gone live (and already prospered) on the innovative comics-only crowdfunding/co-publishing site Zoop. To take a chance on this pioneering creative venture shows nerves of iron, but I sat down by New Jersey-to-Texas zoom with Pitarra to confirm that all his blood and guts are unbreakably connected to a vibrant, benevolent heart.

HILOBROW: When the same person does both script and visuals, I wonder how the writer and artist work with each other :-).

PITARRA: I don’t put on just one hat at any one time. When I just drew comic books, I was only concerned with the sequential narrative. Meaning, this guy chops this head off, this head rolls down — and I was obsessed with that, and I was in the moment. Working with Hickman, we worked Marvel-style [story-conference first, art next, script last] and I realized that you could just pick some plot points with the real estate that you have of a comic, like, by page 5 you wanna establish this point, get this point across, because on page 15 you may wanna turn that point on its head; you need a throughline. [For Ax-Wielder] I’ll thumbnail it out and the book starts coming to me in scenes; from there, if I have an anchor point, [if] I know this three-page fight scene is gonna happen, I can block that in, because I know that that won’t change; the writing around it might change, whatever exposition or dialogue might change, but I know I need that shot and I can lock that in.

I’m drawing this thing at — instead of 11 x 17 [for a page], I’m taking an 11 x 17 and turning it sideways, and doing each panel on its own 11 x 17 board. Then I’m using the smallest pens, the 003 micron and the 005 micron to ink it. While I’m inking it, I’m thinking about the dialogue. And when I read dialogue, I hate exposition. So the whole time I’m putting in the exposition that I want, but then I’m scraping in and refining it to hide it. Like, maybe I need to get something about Ax-Wielder Jon in, and it’ll be a joke from another character instead of somebody coming out and saying it when those two characters in that moment wouldn’t necessarily give you history, because those characters know that history. So how do you get that exposition that you want to say into the reader’s mind, is the big trick for me. So, while I’m inking it, I’ll be writing it a bit more.

When I brought Chris on, he was like, “Well we need a script,” so the script almost came last; because I finally had to sit down, I knew my anchor points and had to manufacture a script out of that; I’ve worked off that script now and slowly built that readers’ copy that you’ve seen. It’s becoming more and more solid. But it’s never one thing — it’s me out having a smoke and I’m like, “Oh my god, this dialogue would work way better if we just moved that scene over here because this guy can make that point!” It’s coming together slowly, I’m excavating that story, and pretty soon, when you put something down, things are forming other things; it’s not a clear-cut process for me.

HILOBROW: It’s interesting that your starting point for this is a distaste for expository dialogue; do you think that partially comes from the fact that you’re also an artist, so you have a sense for how things can be shown-not-told?

PITARRA: Absolutely, I’m very much a show-not-tell person. I don’t like when you can tell the writer’s doing one thing, and the art is doing another. I really want the comic book to function as a narrative from panel to panel that makes you want to turn the page. And sometimes you get a picture-book: you get a picture, and you get the words, and they don’t jibe. The synchronicity for me is always closer to the art carrying it than the dialogue or the caption boxes or whatever.

I’m always hyper in-the-moment. When I worked with Hickman, he was this big idea guy and more reserved, but with me, I’m like down in the panels, grinding, so, I do want the moments to be rich. And I’m always conscious of the page-turns — like, “this line would be good on a new page, or this reveal would be good on a page-turn” — and the functionality of a comic book and how I’m playing it and presenting the story is really important to me, just because I’ve been a sequential artist for twelve years now, so that’s ingrained in me and it always comes first.

HILOBROW: When you’re working with someone else’s script, has there ever been a time when you suggested any restaging of things so there would be that kind of, a certain rhythm to when a line is said, before or after a page ends, etc.?

PITARRA: All the time. What I’m really bad about is adding extra panels. I’ll wanna add extra panels because, those are two different sentiments you’ve got in the same panel, let me break it out and deliver that line in its own beat. Those little changes will change the way the story’s being delivered slightly, but I’ll also do this thing where I’ll get like, “Oh and this guy could be doing this, and he’s scratching his head in the back,” and maybe that is somehow informing the story now?

And I will get off-track if it’s a really tight script, I’m spending so much time living in that panel and building out the worlds and getting the perspective right, that sometimes that drawing just starts taking on a life of its own, and it’s hard for me to be really sterile and treat it as a drawing assignment; it’s a storytelling assignment. And I am telling a good chunk of the story through the art, so it’s hard for me to silence my voice, or — it’s not even my voice, it’s what the characters want to do sometimes. So if someone has a really great script and they bring it to me, I apologize [laughter].

Hickman realized that pretty early on with The Manhattan Projects, so he just started giving me [the plots] Marvel-style. Because it was like, “You’re kinda doing your own thing with a lot of this anyway; I’ll catch you. You play in the moment, I’ll catch you in the overarching narrative,” and we kinda worked like jazz when we did that.

HILOBROW: It blew my mind when you first mentioned you did that of all books Marvel-style, since it’s so cerebral — also literally visceral [laughs] — but it’s so high-concept, it’s fascinating that could have emerged from a jazz improv process!

PITARRA: With Ax-Wielder Jon, I knew the plot points because of how me and Hickman worked on The Manhattan Projects. We had some turns, like, “In Issue 15 this is gonna happen, but in Issue 5 we’ll establish this” — and putting those anchor points in gives you a goalpost, but how you get there, you can meander and play a little bit, but as long as you hit those big notes, you’re getting a satisfying sequential story because I’m living in the panel, but then you’re also getting a whole meal and not just random nonsense because Hickman has the brain for the whole object. So when I [started] working on Ax-Wielder I just thought, “I could do that.” I could pick those plot points out, and sequentially I know I can navigate and get there, and it gave me some confidence to finally write and draw my own story.

HILOBROW: You’re in the top three artists whose pictures I “read,” because so much is going on that… spending time paying attention to your images, I feel surrounded by that world, because your detail is so careful and extensive, that it can’t help but take on three dimensions.

PITARRA: Thanks for noticing that in my art; I don’t know if I’m in the top three to be paid attention to, but I do establish some perspective, think about the environments — they do live off the page in my mind, they’re not just like, “I need to put a door in because I’ve gotta fake a background”; I really want the reader to feel like they’re walking around in my imagination.

Moebius said that an artist encodes reality; meaning that they take what they’re seeing and then it filters through their hand. And that hand doesn’t have to be perfect, it can be a child’s hand, it can be a master’s hand; but if you do it honestly, you are getting a vehicle, a language that will carry a story. And I really like that sentiment, and I realized that when I started reading comic books, the guys that held my attention were the guys that I was walking around in their imagination. And a guy like Moebius’ imagination is so vast that he can hold all of our imaginations in it, where we wanna go check out what’s around the corner. That’s something I aspire to; I think I’m very far away from that, but it’s something I try to do. I do try to get what’s in my head down.

HILOBROW: One aspect of your intricate rendering is the detail in the violence; gore as an artform in itself, though there’s never no reason for it. In this scary era the care in your depiction of violence almost feels like a kind of ward against it, a way to process it… but what is this about to you?

PITARRA: I knew that people have a perception of my work, because I can draw gory sometimes, or over-the-top, and I knew that if I drew this ax-wielder man and he was missing some of his face — and it’s more than just, his face is missing; Jon is this overtly machismo character, he’s like a new version of a modern He-Man toy. But I knew something in the story was gonna harmonize him, from just being a drumbeat. It was gonna add some softness and femininity to him. So, like — it’s a joke to me, but he’s got a big bushy moustache, and his moustache is broken in half, so in that cut alone there’s symbolism of his machismo being broken.

I also thought — I wanted readers to think they’re gonna get this over-the-top, really detailed story, and it’s called “Ax-Wielder Jon” and a lot of the preview art is bloody, but I knew it was gonna be a mask. Any time in Ax-Wielder when I am showing ultraviolence, there’s a part of me that’s a 14-year-old, and is like, “Yeah, I got an ultraviolent comic book!”, but I didn’t want it not to have meaning, so whenever I present the violence, it’s always a front for something softer… there’s a purpose. It makes it more than just a bloody comic book.

When I came up with Jon, my daughter was really sick in the NICU, and I started drawing this big barbarian. People were telling me, like, “You’ve got to give it over to God,” or “Trust the doctors,” and I really wanted to do something. So I started doodling in my book, and I wanted to try to fix it myself, and I thought, “Well wouldn’t it be cool if a guy had this problem where, he always did things his way, and he was gonna fix the world his way, but what if he was just really good at wielding an ax.” That creates a problem for him to grow, because how can you fix things if you always break them. The thing with Jon is, in future volumes [when we learn things you’ll have to read the book to be astonished by! — Adam] is that everything he’s done in his life up to that point, he was a piece of shit, but when he finds this chance to do something good, he realizes that all that was training. And he takes it as the gods saying, “Okay killer — kill like you never have before; kill for a purpose.” And I thought, if I can get that note and stick it, and give a reason for why he’s being violent, then I have my excuse for all the violence I wanna play with. I get to play with my He-Man toys and break ’em and do all that immature stuff, but having that soft note to balance it makes it a piece of music. Rather than just a violent, linear story, which I really have no interest in telling. And I want people to see this other side of me. If I can hit that note, I think I’ve got the reader — when they see a new layer they didn’t expect, all of a sudden you’re rooting for the violence, instead of it just being a spectacle.

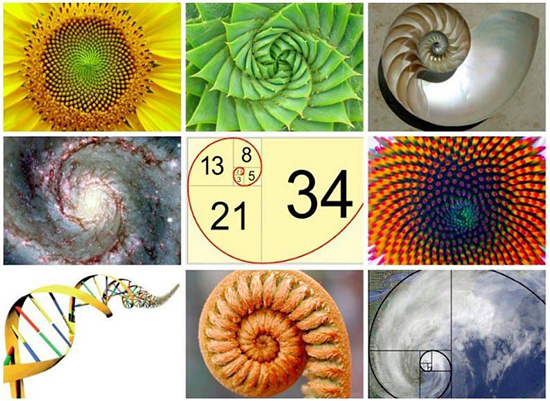

HILOBROW: Beyond just the awesome-factor of the combat, the precision and imagination of the anatomy as it comes apart is unforgettable. Is there a sheer joy of rendering in that, or even a kind of reverence for the mechanics of nature?

PITARRA: It’s half made-up, and half is my friend here [indicates a layered anatomical figure in his workspace]. I try to move the forms around in the cartoony shapes and lines of action, and then I wrap the muscles around — you know the Fibonacci sequence and the rule of thirds, and how plants spindle out — and we kind of spindle out, from our belly button outward? And how muscles wrap around and how all creation is coming out in a spiral; like the conch shell is the same pitch as the pi symbol spinning, or the yin and yang; we’re obsessed with this spiral. I thought that is so interesting. And my sister is a biology teacher, and she’s like, “Oh yeah, from our belly buttons everything kind of spins around.” And when I was trying to draw muscle-men — Manhattan Projects was old guys in suits, so I actually had to think about anatomy for the first time, and I was like “Okay, how does this muscle roll into that,” and to see how the deltoids roll into the biceps and how they overlap was super interesting.

I don’t ever get grossed out with my own art because there’s a levity to it, or a sense of — even [now] I can’t get the charm out of my work, I can’t just make it look cool and violent; there’s something there that’s fun. I think of it as a bedazzling or a sleight-of-hand. I never thought that as an adult I’d get to play with my He-Man toys again. Much less get to do it at a mature level, [see if] I can try to bring it to that.

HILOBROW: That does bring me back to a subject I had in mind often while reading the book: the strange and conflicted history of stories “for kids” — the now-ubiquitous Disney fairytales began as horror folklore, and comics have gone from being considered an artform aimed at kids and bad for them, to one for adults who can’t grow up. What are your thoughts on what kids should or shouldn’t see, and where Ax-Wielder Jon exists on that spectrum?

PITARRA: My wife loves the old versions of fairytales, and we talk about that all the time — they were made to scare you, they were made to warn you, and now they’re all Disneyfied and softened. I was obsessed with that starting this out, because I wanted to get at least a whiff of fairytale-ness in it. I think with Jon… I don’t know who it’s marketed for [laughs]. Hickman read it, and he’s like, “Turn the blood blue, take out all the cursing, and you could probably market this to younger kids, or to like, the 14-year-old boy market, you’d have a big hit.” But what I thought was, if I was 14, I want to make the Heavy Metal magazine that I’m not allowed to have. If I’m 14, I wouldn’t want the softened version, I wanna get my uncle’s crazy comic book collection and find this adult thing. So the only audience I know a hundred percent I made it for, is for me. This is a book that I want. I hope people will want it, I think they’ll be surprised by it.

I was never really protected from media as a kid; my parents were always, “put everything on the table, and this is what this is,” and if you had questions about it they would let you know, so they would let us see mature — I could watch Robo-Cop at like 5 years old [laughs], 7 years old; Predator, I was raised on all that stuff, and — it probably is why I am a little warped, but I don’t think protecting people from it… I don’t think we need to spoon-feed or soften, and put bumpers around everything for children. I know the book isn’t for children, the book is for me — but if you like weird stuff, I’m hoping you’ll like it.

HILOBROW: You’re kind of striking out on your own heroic quest through forbidding territory with this self-publishing venture. What is your vision of the way forward for comics, and for this, almost kind of mutual-aid enterprise as a vehicle?

PITARRA: You’ve got the Big Two [Marvel and DC], which are like two big trees. And you can stay on that tree. But if you see that things aren’t working out, or the tree isn’t where you wanna be, you’re gonna be a seed, and you’re gonna fall, and little substructures are gonna pop up. One of those is crowdfunding. With the concept of social media, everyone gets a voice, and a platform, more so than ever before; there’s not just one media outlet. There’s a lot of power there. Marvel’s already hiring people because of their social media presence. That gives power to the creator. I’m going to publish everything under a brand called Karoshi Comics, and I hired Chris Stevens as my editor-in-chief to come in and oversee a line to help all of us writer-artists bring our debut books to market.

I love storeowners, and storeowners are gonna get 50% off and free sketches on any books they order from us. But some of those stores are cash-strapped and they only wanna go to the names, to Spider-Man or Batman. Me on social media, I can bring it to the fans directly, perhaps I can generate the revenue that I need to make this self-sustainable. And if we’re all building our own email lists, and I get 500 or 1,000 customers — my next buddy is Garry Brown who wants to do a book under the label. If I say, “Garry, I don’t want you to have to start from zero emails, here’s 500 for you, when you’re done collecting yours, share yours with mine”; if we keep doing that, four or five times over, we will have a reader base that would equal the pre-orders if a book was at the Big Two. I’m not saying it’s as big as the original tree, but it could be a new way.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE