OFF-TOPIC (29)

By:

May 5, 2021

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, marking a grim anniversary with a gracious remembrance, as America’s wounds are again shown to be nothing new and the optimism of those who truly observe its ideals never gets old…

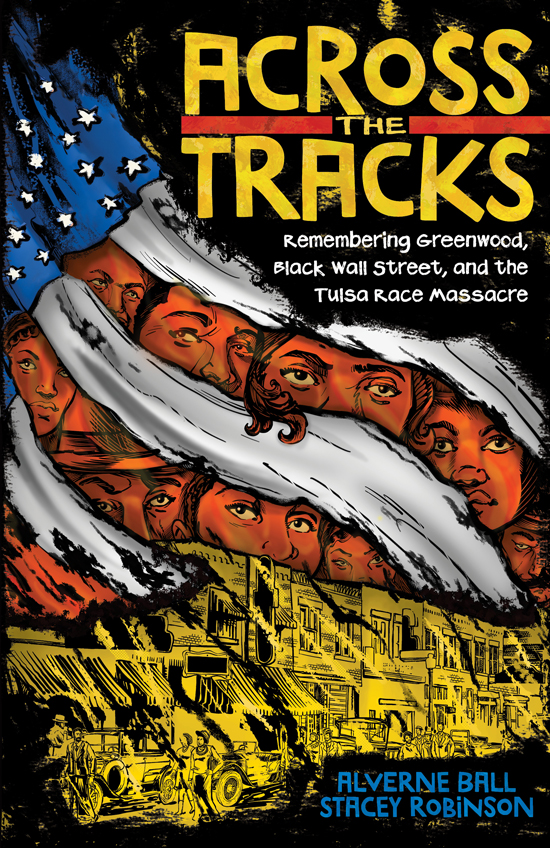

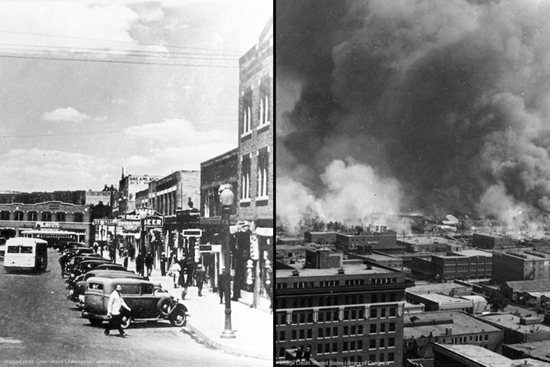

History usually needs two or three times to recur as history. Its first drafts are the most embellished, as dictated by the winners, and the truth spends decades or centuries in exile disguised as fiction and passed along in a whispered tradition. So it was that the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 broke the surface of the American mass consciousness after a near-century of awareness in the African American community, as the most hard-to-believe aspect of a TV show (HBO’s Watchmen) in which it was the only real-life event. It seems fitting that two storytellers should return to that series’ vernacular source medium to set the record straight and tell the whole truth. That’s what Alverne Ball and Stacey Robinson have done in the succinct yet sweeping graphic novel Across the Tracks from Abrams ComicArts’ MEGASCOPE imprint. The title refers to the rail line that ran between White and Black Tulsa, Oklahoma, a seam stitched across invaded Native land on which its newer inhabitants stayed separated, and in relative isolation Black settlers built a prosperous, self-sufficient community that came to be called “The Black Wall Street” (centered on Greenwood Ave., by which this neighborhood was most commonly known). In due course, the lost-kingdom narrative that spellbinds White supremacists but is in fact serially committed by them came to pass, and a trumped-up charge against a young Black male lit the spark of White resentment and envy of Greenwood’s independent achievement. Literally, as the community was bombed and burned to the ground. Across the Tracks is one way in which the wiped slate of this short-lived promised land is being sketched back into being. The fond recounting of Greenwood’s rise and fearsome portrait of its untimely destruction — as well as both the endurance and immediacy of its fight back to life — tell a tale of tenacious hope and no choice but to face forward. I spoke with Ball and Robinson about the reckonings behind this book of history they have helped reopen…

HILOBROW: The expository tone and often-charming illustration style almost make this feel like a storybook for adults. Alverne and Stacey, did you feel as if, on some level, the book had to start back at the earliest modes of narrative most of us encounter, to rebuild shared history that most of us have missed?

BALL: Interesting question because I don’t know if I was thinking early modes of narrative but when the story started to take shape I did want to start at the earliest entry point into how African Americans found themselves in Tulsa, and what was the catalyst for the building of Greenwood. From there the story kinda took on a life of its own, partially because brave people took it upon themselves to document as much history as they could find and remember, and the [story] beats or the pieces of the puzzle started to fit together in a way that I could not make up, as these events actually occurred and all I had to do was follow the breadcrumbs.

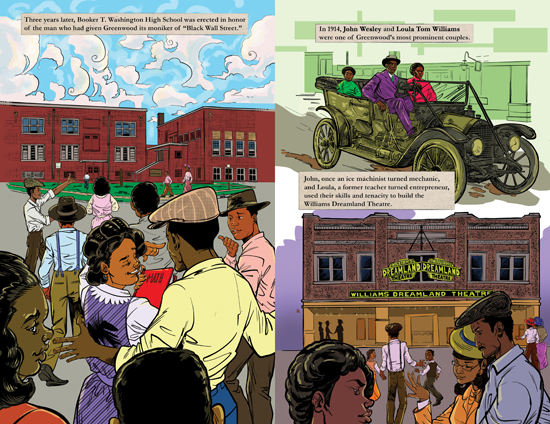

ROBINSON: I felt like, this is the fifth graphic novel project, in addition to various freelance projects in the last five years, addressing Black trauma and death that I’m a part of producing. At some point I had to find areas of joy to ground myself in. I teeter between the whimsy of children’s book styles like Ezra Jack Keats, and then more teen or adult comic styles and many musical influences. I pulled from the influence of so many apparent inspirations whether it’s Kyle Baker, Matt Baker, or Anita Baker because they help tell this story of how I got here. Many of us typically know about the destruction of Greenwood, yet are unaware of the rebuilding of Greenwood. I wanted the audience to understand that these Black people had joy. That our history, this part of American history happened in full color, and full Black opulence.

HILOBROW: There was so much information, and many mythic figures, to cover in this book’s short space. Alverne, during the development of this story did you consider focusing on the arc of a single everyday resident or family, or did you feel it was most imperative to make sure all these names-we-should-know were visible, and let the reader imagine what daily life was like in the world created by these towering founders?

BALL: Originally I had pitched the story to follow five different characters, each to be a different representative of the Black experience because as Black people we all know that our experiences might be shared but we also know that we don’t all come from the same economic or social upbringing. At some point in the creative process that idea got shelved and when Abrams asked if I could do a more non-fiction stance on the book, I knew instantly that the story had to be about the people of Greenwood and who they were, and even less about the tragedy that befell their community. Now that’s not to say that the mass destruction of Greenwood isn’t important to the history of this country, but I was more aware that I wanted readers to know that it was regular Black Americans doing extraordinary things to define their times and rise above their “pre-determined” station in life. I also wanted readers to see that the same entrepreneurs that existed back then exist today in neighborhoods all across America, so the times may have changed but the narrative is still the same.

HILOBROW: Related to that last question, Stacey, it’s ingenious the way your panels sometimes feel like a collection of vintage personal snapshots or news photos, and other times feel like the candid motions right after an old-school picture was clicked, and yet others give way to full natural sense of motion. Did you seek to convey the fragmentary way in which we’re able to look back on this time and place?

ROBINSON: I think I’m a pretty good storyteller. I felt like I was taking a journey as I read the book and I wanted to translate that to the reader as well. I think the story deserved that. As a graphic designer and a golden age Hip-Hop fan I try to move the crowd and take them on a ride through the adventure as we end up somewhere with a story to share. Yet at the same time I wanted the audience to pause and experience the moment. I’m gonna make you feel and see what was destroyed, and why.

HILOBROW: Alverne and Stacey, what kind of discussions did you have on setting the pace of the storytelling? The way the calm of Greenwood’s glory days gives way to the carnage of its demise is startling and expertly timed, like history falling off a cliff or a curtain being ripped away. This is an elusive, third layer of narrative that’s neither entirely textual or visual; what kind of conceptualizing went into it?

BALL: Stacey and I didn’t get a chance to discuss pacing because we didn’t have time to formally meet before I started writing the book. But storytelling for me is about feeling the story come together naturally. I always say that I see story like Ray Charles heard music so for me I could hear and see the beats of the story. I could feel the story coming together and it was guiding me. As I wrote the story I imagined these bigger-than-life individuals and I felt as if I was standing upon their shoulders trying to measure their greatness and ultimately finding myself in awe of their achievements. The proverbial “calm before the storm” was I hate to say serendipitous of the times when one looks at the historical context of Greenwood. Notice that the biggest African American hotel, a crown jewel of Greenwood, the Stratford Hotel, is completed and then we turn the page to receive the news of Dick Rowland and his impending lynching. These two events are almost counterbalances that represent the good and the bad of what Black Tulsans endured just to have a sense of peace and safety in their own state and in their own city. One can even say it is a much larger representation of the Black experience in America.

ROBINSON: We decided that it wasn’t going to be a story about Black carnage, Black bodies ripped apart, riddled with bullets, burned alive, dragged through the streets. This wasn’t going to be a fulfillment of Black torture porn fantasies with no end resolve of justice or revenge. We see those images, whether past and even present, sometimes live on social media, with so little justice that we’re surprised when there is the slightest sense of it. This story wasn’t Alverne’s original vision for the book. The original was a much greater narrative, a lot more personal, in my opinion more empowering. The final product was however “a great compromise.”

HILOBROW: There are some moments of storytelling in the book that are wholly visual, like the spread where a fragmented collage of scenes from the massacre plays out in different panes of the same window, more jarring than any broken glass. Stacey, what decisions played out in your mind regarding what parts of the story were beyond words?

ROBINSON: On those particular pages Alverne wrote a lot. I couldn’t have drawn it all, or maybe a much more experienced artist could’ve. I also needed to meet the deadline. I once again pulled from storytelling and graphic design experience to create a deeper narrative. On these pages, we see what the Greenwood residents see. I put us in the room with them. The reader is also under attack. If we were there, at that moment, what decisions would we make to survive? Some of my favorite pages are the pages when the residents arm themselves to march downtown to free Dick Rowland, the teen falsely accused of assaulting a White woman. There is very little dialogue, but pages are full of understandable action. Once again, we are in the crowd marching with them. Me as the artist and the audience as the reader have no choice but to involve ourselves. The reader is on the side of Black justice whether you want to be or not.

HILOBROW: Alverne and Stacey, it’s common to ask what true tales like this have to teach us (and sometimes condescending, since there’s always some of “us” who have known about it all along). This particular story is one in which you don’t even have to reach to show direct parallels and repetitions in history — the restriction of health and rescue services by one “side” to the other; the tent cities of refugees; the military hardware on civilian streets. So maybe the question is really, how can we as a society learn from what stories like this prove we never learn?

ROBINSON: I don’t think that’s the right question. We already know the lessons. 100 years ago, Black people were punished for uniting, being more affluent than White people, and for having ambition. America is circa a century from Red Summer, “Spanish Flu,” WW1, Women’s Right to Vote, and the Tulsa Race Massacre. Some historians have argued that times were better then for Black people than now. The first summer of the Biden/Harris administration is almost upon us; we will be a year and a half into the COVID Era and a year from the blazing hot summer of 2020, yet with no enacted order in defense, protection, and restorative justice for Black people. The right question in my opinion is what are we, as Black people, going to do about securing our own futures: spiritually, financially, militarily, with sovereignty, and governance. All the elements that define any nation’s existence and global acceptance. Due to our strategized subjugation, we are again at America’s mercy, and that of a president who said “we ain’t Black if we don’t vote for him.” Well, we did vote for him, we still Black, and we still suffering. But we count a victory in electing the first woman VP who is also a woman of color…

BALL: I think stories like this, just like stories of the Holocaust, teach us the barbaric acts that we as humanity can justify upon our [fellow] humanity, but in seeing and recognizing the lies that brought forth the violence, terror, and death I hope that we start to rethink as a society what those justifications mean to the greater idea of our future as a species. If anything I hope stories like these inspire us to see what greatness can be achieved if we put more of our efforts towards growth and development instead of allowing tyranny to rule over us.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE