OFF-TOPIC (25)

By:

December 17, 2020

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For the current year’s last call, a sift through the sheaf of separate and collective memory’s mental images, with compared notes on what can’t fade and what gets exposed…

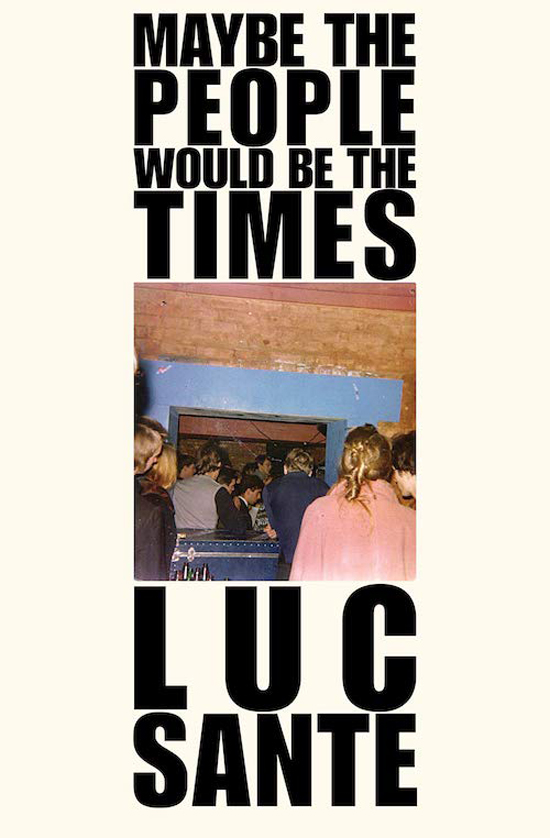

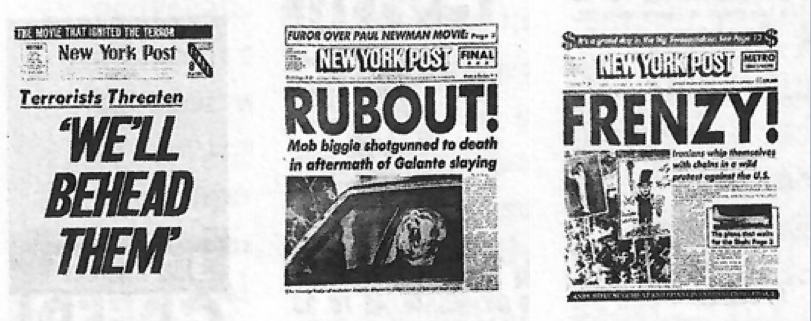

The essence of legend is that if you weren’t there, you remember it. It grows in the telling, but someone had to let it go at the start. Only long after do people want to hear from anyone who saw it happen themselves. A spirit guide to the places others typically visit at most and avoid if possible. Maybe the People Would Be the Times is a collection of what its author Luc Sante didn’t keep but did come back to him; essays, reminiscences and reveries assembled as if blown down the alleys and sidewalks of personal history and whirled together by the backward winds of time. Revisiting (or revisited by) his youth in the booming bleakness of Manhattan’s late-1960s to early-’80s cultural outlands, the worlds of Warhol and grindhouse and Punk and decay, Sante’s metaphor, method and material are scraps and glimpses, a piecemeal epic told on gig flyers and manifestos pasted to walls, tabloid photographs never meant to be remembered, souvenirs from clubs and theatres that no longer exist, indie art and music and lit that left only traces; the patchwork narrative mirrored in the clashing waves of immigration and primeval weave of hip-hop he was there to witness. Sharply sketching departed friends and undiscovered giants, painting whole communities and ways of life in the spaces they’ve disappeared from, vividly shaping his life story not from his own likeness but from everything that happened around it, Sante understands that we are all peeled out of and collaged into each other’s memories, and the most accurate image of humanity is a composite. His younger self traversed the romantic ruins by instinct alone, and his later mind retrieves a shining, clear conception of it which lasts and lives and speaks to those who find it next. Fittingly, we traded thoughts by the almost antique means of email, fully in touch but not meeting in this life…

HILOBROW: There’s remarkable emotional recall in these essays for someone who says that so much of it was experienced in a haze — are many of these experiences the kind that you remember better at a farther remove, when they’re more of a corpus, or time has decoded them so to speak?

SANTE: I don’t seem to have a hard time remembering emotions, ever. Physical details and such do slip away, though, so I guard and tend my memory like a rare plant, and get totally freaked out when a friend remembers something I’ve forgotten. But writing about memories is a different matter. I started trying to write about some of these subjects when they were still alive and in progress, and it didn’t work. Even a ten-year remove wasn’t enough; maybe not even twenty years. I need the distance of time to put a frame on things and eliminate all the petty jealousies and resentments that obstructed my view.

HILOBROW: The second-person pronoun is used uncommonly here — not to provide a dimension of distance and evasion of direct confession as in, say, Junot Díaz, but more like the conversational subject-less “you” that means “one” — but applied to a very specific set of memories and perspectives. Do you wish to only contain your insights to your own head up to a certain point?

SANTE: Yes. In the title essay, for example, I was setting out to render, for the benefit of younger readers, the shared experience of a microgenerational sample of which I was a part. To present my own particular experience would only make things confusing. I’m a working-class European immigrant, for example, and to this day I’ve never yet met anyone else in this country who is all three of those. There are many, many things I can’t write about because they would make no sense to anyone but me. Even when I was experiencing the things I depict I was to some extent employing a collective lens — looking at the scene through the eyes of my friends and people in the crowd whose lives I could only imagine, as a corrective to the inherent flaws or idiosyncrasies in my own vision.

HILOBROW: There are many testaments to the immaterial here — famous performances that only a handful of people personally saw, small-run publications that made significant impact on you but which no one else may have ever heard of. If seeing something is what creates it, is remembering something what confirms it existed?

SANTE: Immateriality preserves experiences for literary purposes, for one thing. Otherwise they get lost in the noise, become part of a streamlined official memory that supplants the real thing. I saw Paul Simonon destroy his bass at the Palladium — the cover photo on London Calling — but so did hundreds of other people, and hundreds more think they did, and the event has entered the realm of myth. I would never write about it, because there is nothing I could add. My approach to subjects in general is to pick things that aren’t already covered with fingerprints — unless I have a particular angle on the subject that hasn’t previously been recorded. And note, too, that certain particularly immaterial items in the book are so rarefied because they are fictitious.

HILOBROW: The slippage of register between the current moment, what led to it and what later comes of it, like nesting boxes of blindness and context, the view up and down the crossroads of each frame of time in every direction, is navigated better than I’ve ever seen outside of Edward P. Jones’ four-dimensional exposition and some of Nikhil Singh’s agile tense-shifting. How do you traverse that without getting lost? If these same accounts had been written ten years on or back from when they were, would they be drastically different?

SANTE: I have a pretty solid internal map of time; I always refer to those Saul Steinberg drawings in which decades or centuries are represented as shelves or drawers. And as noted above I have a pretty clear recollection of my internal state at any given point — what I didn’t know yet, what I had just learned, what I was still in thrall to if not for much longer, etc. I guess the key to representing such recollections is to be far enough removed from those emotional circumstances to be able to see them unencumbered.

HILOBROW: Related to that, there’s a faceting to the book’s narrative trajectory — we see some of the same subjects from different angles, and they play different roles, at different times (like your neighbor’s fire or your neighborhood’s building collapse; sometimes background noise and sometimes central events). Are our memories, and our times, mosaics whose puzzle-pieces spend the rest of our lives falling more fully into place?

SANTE: At first I was having a hard time putting the collection together because there were so many overlaps between pieces, but then I realized that the overlaps were a feature, not a bug. The pieces were originally each written for a purpose and in a context. The collapse was written as fiction (a number of items in the collection are salvaged fragments from an abandoned novel) and the fire was written about in a New York Times deaths-of-the-year memorial piece about Rene Ricard, and then the collapse and the fire both figured in a New York magazine piece about the phenomenon of apartment-house neighbors — the focus is slightly different in every case. Our lives may be mosaics, but their pieces are always in flux, depending on circumstances and contingencies. There is no “place.”

HILOBROW: I seem to perceive a mysterious shared gauze and graininess in the childhood photos of everyone I know, no matter how recently or long ago they were born. It’s as if the scroll of the past keeps rolling up behind us, imparting an antiqueness as it goes. Is this some extrarational intersect of subjectivities, some collective tendency to get immersed in someone else’s frame of reference?

SANTE: It’s hard to distinguish between the fog of memory and the relentless galloping pace of technological change. My early childhood photos, taken with a Voigtländer folding camera, unsurprisingly look as if they might date from the 1930s; my later childhood photos, taken with a Kodak Brownie, just look like the ’60s. But then I see pictures from the ’90s, taken with a point-and-shoot, and I’m startled by how faded and distant they already look. Every decade seems to have its look, imparted by whatever the format was then — I don’t know if you can generalize further than that. Anyway, black-and-white will always feel like home to me; color is something new I’m taking for a test drive.

HILOBROW: Paradoxically but by definition, we are all outside the frame of our own perceptions, though too many memoirs are marred by an overconsciousness of presenting oneself and being seen by the reader. Your own accounts are rare for the unintrusion of you as the story, and in your biographical sketches and overviews of oeuvres you’re the rare critic who seeks to complement their subject rather than compete with it. Those are also all written outside of the friend or famed person’s lifetime. Are the best portraits made without a sitter?

SANTE: Well, they’re certainly the best in my case. I find it almost impossible to write about the living, because of the inhibition of tact and even more because of my dread of getting things wrong. Also, I’m old enough to have experienced the Norman Mailers and Hunter Thompsons on the hoof, so I’m keenly aware of how foolish it is to pretend to be writing about subject x or y while keeping the focus trained on yourself. (The irony is that if I were asked what this book is about, I’d have to say that it’s about me.)

HILOBROW: At some points you counter the melancholy of whole worlds, even recent, that now exist only in photos, and of anonymous lives whose full story will never be known to most who view their images, with the slapstick of misinterpretation (i.e., the false histories that gather like antibodies around a cheap paperback cover, a promo pic of Hank Williams, even your own juvenile artwork, in hilarious satires of imposed context and assumed narrative). And of course one hallmark of the random passersby snapped by Vivian Maier, whom you write about here, is how often they are glaring down the camera with suspicion and hostility. Does the past even want us to remember it? (And how hard really is it for us to infer accurately from what we’re shown?)

SANTE: The past is always in flux; the subject changes with every viewer. Whenever a writer releases a work into the world it becomes fair game for any number of readings, all of which will depart from what the writer had in mind. Every instance of reading, like every instance of writing, is an act of interpretation. There are possible wrong answers, but no right answer. Speculations and alternate histories are readings that are allowed a cadenza passage. The trick is to get them wrong the right way.

HILOBROW: Related to that is the roving eye of the street photographer, whose role as witness, as thumbnail social historian is priceless to us now, but whose intentions may have been strictly functional (crime-scene documentation, tourist souvenir portraits) or whose motivation may never be known (as with Maier’s own fully private practice and only posthumous recognition). All these floating eyes faithfully recording everything but hovering just out of sight, like…a conspiracy to do nothing. What is the watcher’s true purpose in our existence?

SANTE: Intention is, for me, the glowing mystery at the heart of photography. I’ve always wanted to assign fifty photographers to take a picture of the same subject with the same equipment and the same settings at the same time of day. I already know that the result would be fifty very different pictures. The great thing about vernacular photography is that its practitioners were always operating under a set of constraints that precluded “art.” They were thinking about clarity and information and their deadline and their paycheck, so they avoided fancy angles and lighting effects and got straight to the point. In a time when art photography still suffered from an inferiority complex (I’m most interested in photography between the late nineteenth century and the mid-twentieth), that made them much more valuable as recording agents, and if they incidentally made art in the process so much the better.

HILOBROW: The history of the everyday was untold until the middle class and the camera were created, and mostly scattered into invisibility between then and when social media arrived. Now the canon of ordinary lives is saturating in its presence, but ephemeral in media and possibly unreadable in profusion. After I started writing this question I saw that Insta was using the slogan “We Make Today”; even with this unprecedented capacity to record ourselves, could it be that we don’t really want more? (And does that say something about a shift in how we see our position in the stream of being?)

SANTE: I guess you’re really asking what the present will look like in fifty years or a century, provided the human race makes it that far. I don’t think Instagram etc. will kill photography any more than photography killed painting, which everyone was predicting in the nineteenth century. All I know is that some factor — some technological or societal change — will make what we think of as total image saturation look very small and specific and particular to our time, and eventually as precious as the fugitive images of the past look to us.

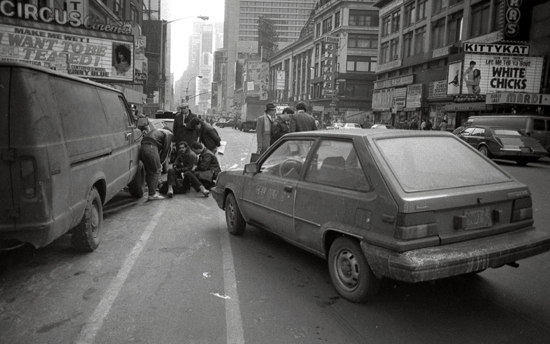

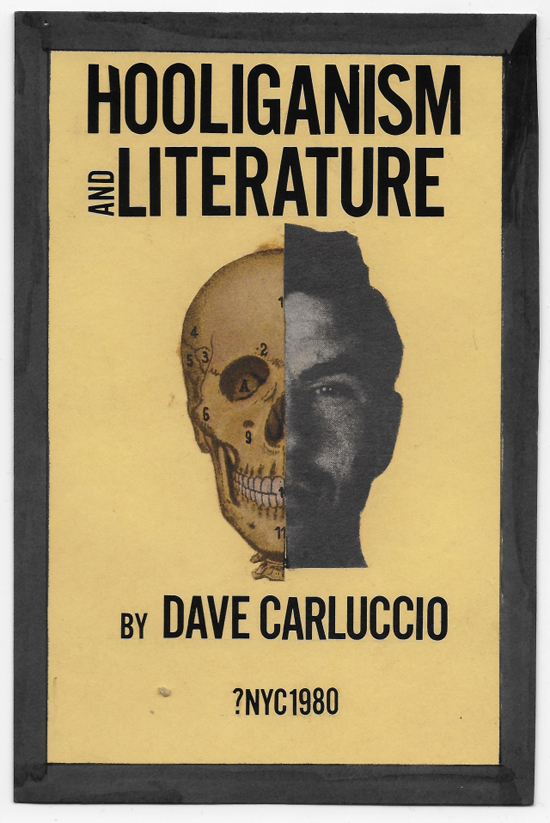

[Images (top to bottom): Sex & death in Disney-topian midtown NYC, circa late 1970s (© Bruce Barone); the cover to Sante’s newest book (Verse Chorus Press); postcard biopsied from strata of olde NYC street-poster massifs (Sante’s collection); chapbook cover design by Sante for his own pseudonym, edition of none; collage-in-quarantine by the author, 2020 (from his website); three classic tabloids of many in the book’s illuminations; unidentified mid-20th century Vivian Maier stealth-portrait (© 2020 Maloof Collection, Ltd.); street-music and apparent prayers, in posthumous New York (© Bruce Barone).]

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE