OFF-TOPIC (24)

By:

November 11, 2020

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, a secluded consultation on human fragility, contagious notions, and which bubbles it’s best and worst to leave…

Who is there to write the stories that never finished? And do we really have to know how ours turn out? In the canon of past human experiences that others can’t imagine, many are known to us mainly through imaginary works — plays and poems and paintings about long-ago wars and disasters and injustices. Some of the best-remembered works about trying times are themselves about storytelling — Scheherazade spins tales that put off her own execution; the gentry of The Decameron make up stories to distract themselves from the plague they’ve fled into the countryside. In our own global health crisis, we’ve got journalism and social media to rely on but are still looking for what those who lived through similar times — and didn’t — have to say to us, and wondering what we have to tell the future. This is a narrative that will be revised as long as the human race exists, and one of its most enlightening editions is Heather E. Quinlan’s Plagues, Pandemics and Viruses: From the Plague of Athens to COVID-19, put out by Visible Ink Press.

Started two years before COVID struck (just lucky I guess) and right on time for a season of soul-searching on how it could have happened and what happens next, this pop history pulls compelling personalities from the faceless numbers of devastating disease — like “The Searchers,” 16th-century widows charged with being census-takers of the afflicted in return for the state welfare they received (thus becoming perhaps the first public-health statisticians). It traces the ways in which deadly biological agents have travelled as companions of entirely human pathologies — like the decimation of indigenous populations by conquest and infection alike. It surprises with the ways that pandemics helped create the middle class and cultural renewals, and makes sense of medical history, virus science, and how to survive and make life worthwhile in the current emergency. It checks in with a pastor, an imam and a rabbi for philosophical context (the first of whom has memories of a mother who survived the 1918 influenza); records how the extended, multiply-parented modern family is coping with the problems of distance and togetherness; and talks directly with Dr. Anthony Fauci on how to stay safe and what baseball team to root for. And miraculously, is great for passing quarantine-time while feeling fortified, not frightened, by the knowledge that’s being transmitted and the tale we’re still here to have told. Being, full disclosure, Mr. Heather Quinlan, it was perfectly safe to sit down and discuss how we all get through this, and what was going through her head…

HILOBROW: This is that relatively rare work about mortality which is grounded in fascination but not morbid curiosity. What is the source of your interest in the subject, and how do you navigate what could be the exploitative aspects of that?

QUINLAN: I think it does stem from an interest in mortality, and… possibly because I’ve experienced a lot of death in my family, and much of my life and my life choices have been the result of deaths that I’ve had to go through. So, I guess some people would not want to pursue that topic, but for me it became something that was almost a companion to me. And I bring that with me everywhere I go. Therefore, since it’s such a… since it’s a topic that we know so much and so little about, and there’s art and there’s music and there’s writing, and all these things that derive from death, I guess what was the initial reason for me getting involved in this book is an offshoot of that interest, or better word, fascination of mine with death. And because it is a fascination, and not in a goofy, weird sense, I think I naturally treat it with a certain amount of reverence and respect. I think some of the people who play roles around death and pandemics and illness can be buffoonish, but the victims themselves are not. So I would think of it as [being] how I would want someone to treat a subject that maybe my family had been victims of; I would not want them to mock it, so I treat it with the same respect.

HILOBROW: What was the most intriguing thing you yourself learned from doing the book?

QUINLAN: Regardless of what the disease is, there are two things that kind of work in tandem: one is the struggle to live in the face of death; whatever that is within us that wants to keep us on this planet, even when people are dying all around us, is powerful. And the other thing is, I think people are wired, unless you were trained in the medical field — and mind you, everyone who reaches a certain age has a certain amount of medical knowledge, down to putting a band-aid on a cut or icing a sprained knee — but unless you are medically trained, and maybe even when you are, there is that human need to put a face on an enemy, to have an enemy. Therefore, if you destroy the enemy, you are saved.

So because they were unable — up until the 1700s really, once they invented the microscope — there was very little progress in medicine from the time of Hippocrates in Greece and Galen in Rome, which was a thousand years earlier, so they kind of knew about germ theory — they didn’t know that they knew it [smiles], they kind of knew that [disease] was spread through the air, but they thought it was spread through smelly air, so that people who worked in smelly jobs were the ones carrying disease. Because they didn’t exactly know what was going on, they had to blame someone, and if they eradicated the people who they could blame, then they felt safer.

So for instance during the Black Death, the Jews, who kept to themselves, had their own community, but also intermingled with the wider European community in terms of banking and lending… it was a combination of feeling threatened by “the other,” owing money to them, and feeling the need to eradicate an enemy. So, many, many Jews were murdered during the Black Death, because people believed they were poisoning Gentile wells, and spreading disease, and killing children. When actually none of that was true, and Jews tended to have a lower mortality rate than Gentiles because Jewish law stated that everyone had to wash their hands after they used the bathroom; so they were naturally more hygienic and less likely to spread disease.

If you have an enemy, you can destroy them and feel like you’re making some kind of progress. These were people whose whole world was based around the Church and the Pope, and the Church and the Pope were not helping. So people had to take matters in their own hands. That continues to happen even today, in terms of blaming China, and, “this was a disease that the Chinese deliberately let loose,” or accidentally let loose, or the Chinese are filthy, and that’s why all these diseases come from there, or the Democrats started this whole pandemic as a way to get rid of Trump, and then once Trump is out of office the pandemic will magically be over — all these things, because people can’t see the virus. They can’t see an enemy. But they can see other people [laughs]. The virus is the enemy, but because they can’t see it, and because also, I believe, people do not get a sufficient education when it comes to illnesses and bacteria and viruses, they behave the same way they did during the Black Death.

HILOBROW: That leads right into a question I was going to ask about what you feel is different between how people reacted to past pandemics and how the world of 2020 responded to this one… now I can ask you if there are any differences?

QUINLAN: Even recently, with the polio outbreak, people really banded together, and started the March of Dimes, willingly did not swim in public swimming pools, protected — since polio affected children much more than adults, took care of their kids as much as possible. And as far as I know, did not blame a community for this disease. So, it was a completely different world, even going back 70 years now, because not only were people really unified in trying to find a way to cure this disease that was crippling children… and the fact that it was striking children, too, was really a great rallying cry for people. I maintain that if COVID had struck children the way polio did, then a lot more people would be taking a lot more precautions than they are now. I feel like the “wrong” populations are being affected by COVID; not little kids. Not that I want little kids to be affected by COVID! But it’s, again, a great visualization that people can have, little kids on crutches, and how sad. And, even Jonas Salk, when he was developing the vaccine, tested it out in his kitchen on himself, his wife and their two little boys — you could not even fathom that these days; first of all, that someone would work independently without your AstraZeneca’s etc., and that he would give an untested vaccine to his children. These are amazing ways of thinking that happened in the blink of an eye ago. So polio is one example of how people behaved differently in many ways.

HILOBROW: And when I asked, I wasn’t imagining that you’d say our response has gotten more callous and less courageous or self-sacrificing over time. This is relevant to what we can foresee regarding the course of future pandemics. You write about how factors like encroachment on wild habitat and climate change will affect the prospects of humans coming into mass contact with other pathogens; does your study of what happened before and is happening now give you a sense of what we can expect?

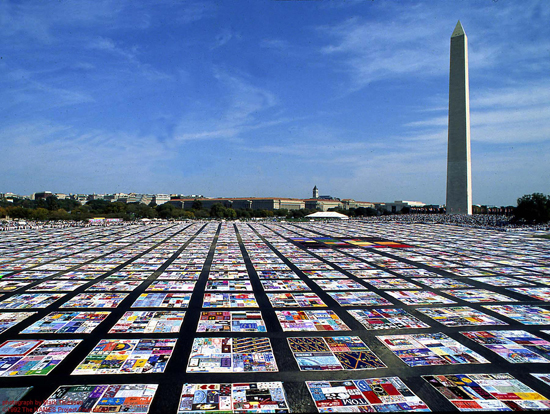

QUINLAN: I can say with great assurance that many of these illnesses — if not all, but certainly the ones that have made headlines, your Ebola, Zika, Yellow Fever, AIDS, are the direct result of deforestation in terms of humans moving into areas where they have never been before, and therefore coming across [animal-borne] pathogens — which are invisible, so you don’t know what you’re getting into when you go into these places and cut down trees. As David Quammen, who wrote Spillover said, If you shake any tree, a bunch of viruses fall out, so just imagine the amount of trees in a jungle that are shaken once they’re cut down. I almost feel it’s amazing this doesn’t happen with regularity. The fact that we haven’t had a pandemic to this degree since 1918 is unbelievable to me due to the research I’ve done. I feel like we got very, very lucky, and that unfortunately has not served us well now; because for things like SARS, and H1N1, [since] neither of them ended up being the apocalyptic pandemic that people had thought they would be, we [assumed] this would be the same. We feel, as human beings, that we have dominion over the planet, and it’s God-given. And that’s certainly used as an excuse when they’re chopping down… the world that God has made for us, and destroying all that has been put in place. These things are put in place for a reason, we should stay out of them, they’re not there for us to chop down and create huge businesses and buildings. We have no idea what’s in there, between the animals that can bite us, and…also, with global warming, the permafrost that has been encasing viruses for millennia are melting, and we don’t know what will spring from that either. We displace people too, and force them into places where they have to eat animals they’ve never eaten. We don’t know exactly what caused COVID, but people don’t realize that bats, for instance, carry an enormous number of viruses in their bodies that do not affect them but do affect us.

HILOBROW: You draw on many historical accounts, and creative works, some of them ancient, to paint the panorama of the human race surviving through mass disease. What do you think will be the best means to convey to people in the future what it meant to live through this?

QUINLAN: It’s difficult to say, because I think that people create their own universe, and one that suits their own narrative. So, we could have people screaming “don’t do what we did” for generations to come, and people are gonna be like, okay, and they’re gonna do what they wanna do anyway. If we were getting messages from people back in 1918 talking about the horror they went through, I believe we would say, instead of, “Oh, we should really take note and take precautions,” we would be like, well, that was 1918; we have all this medical knowledge and equipment and technology, we have nothing to worry about. It’s that arrogance that I think… keeps us alive in a lot of good ways, but it doesn’t work for everything, and when it comes to nature, and illness, and disease, arrogance is something you really have to throw away, because you are powerless against disease of that magnitude.

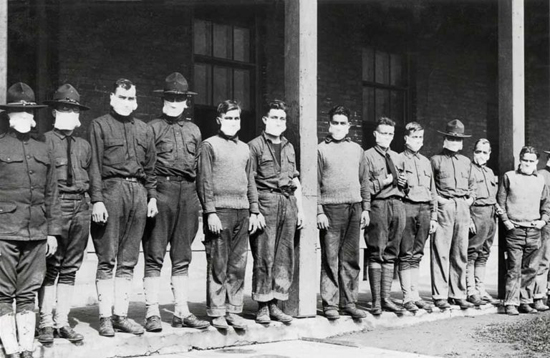

As compared to 1918, where it’s so hard to find any firsthand accounts of it, because it was so misunderstood, kept under wraps, World War I, etc., etc., I feel like, if people a hundred years from now — say, when the next enormous pandemic happens, if we’re lucky enough that it happens a hundred years from now — when they look back at us, if they’re able to read multiple Twitter feeds and see what is going on and see how a disease has been politicized, I think they would think we were stark raving mad, and it would be difficult for them to identify with us. In the same way it’s difficult for us to identify with people dressed in Red Cross gowns in makeshift hospitals. It’s almost like looking at a different species. We can only just hope that people will take heed of what happened during this pandemic…but, I hate to say, people have short memories. So, how this is going to stay in people’s memories who live for a very long time after this, and people born much later who never experienced it, I really can’t tell you.

[Images (top to bottom): The book’s cover; soldiers facing WWI and the influenza pandemic it spread; The Dance of Death (1493) by Michael Wolgemut, from the Nuremberg Chronicle by Hartmann Schedel; the AIDS Memorial Quilt covers the nation’s capital; anti-mask protest, Wisconsin, August 2020]

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE