PANEL ZERO (7)

By:

October 18, 2018

Being one in a monthly series of deep-cutting, far-drifting discussions on the comicbook artform and its cultural influences, expressive aspirations and unintended consequences.

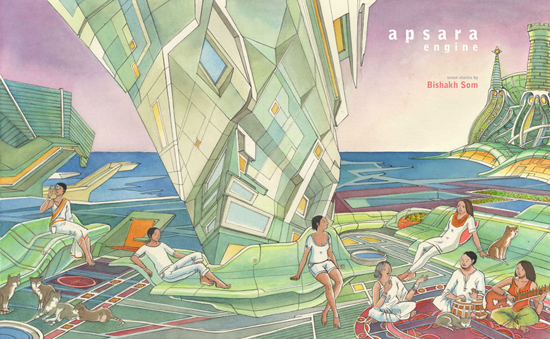

Wherever you are, you’re already gone. Climates transform, landscapes are replaced, populations shift and leave whole worlds behind. Without moving we can find ourselves in not the country we thought we lived in, and become a different person we always really were. Bishakh Som makes the art that changes before your eyes; folding cultures from opposite sides of the globe, traveling a border between rustic urban spaces and the gleaming organic future next door, incarnating every kind of human identity but never just one idea. Exhibiting internationally and publishing or presenting comics in academic journals, literary anthologies, poetry books, performance spaces and other dimensions the medium didn’t know it could go, trained as an architect and gifted in a lyrical vision beyond the possible, Som’s art and story leave no one unchanged. Her most recent two realities — the idiosyncratic idyll of an afternoon on the beach, “Love Is Like a Cephalopod” from We’re Still Here: An All-Trans Comics Anthology (Stacked Deck Press) and the prophetic sci-fi fable of nomadic healers, “Karana” in Beyond II: The Queer Post-Apocalyptic & Urban Fantasy Comics Anthology (Beyond Press) — led us to talk about what the world looks like on this turn and its next.

HILOBROW: Did you have any particular directives when you submitted to either the We’re Still Here or the Beyond II anthologies or could you just go with whatever kind of genre or subject was moving you at the time?

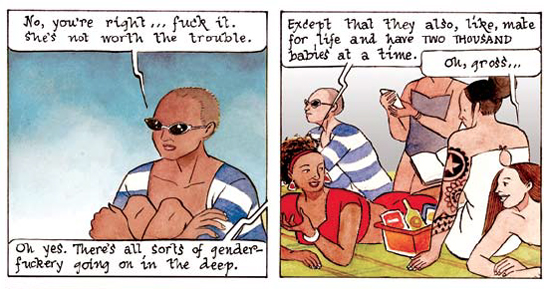

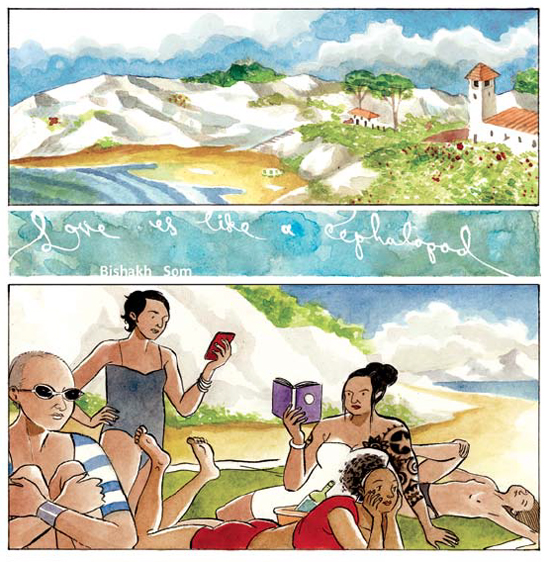

SOM: For We’re Still Here there weren’t really parameters, they [just] asked me to submit something. There’s a couple of conversations that are going on in the Trans community, about our representation in comics. And that has to do with Trans tropes in fiction, recurring motifs, like, The Coming Out Story, or The Transition Story, or motifs like looking in the mirror, and reimagining your identity and things like this. Those are things that I wanted to avoid. And I was thinking, what’s the most, sort of — not mundane, but a scenario where the characters’ Transness is sort of a given, and it doesn’t have to be made a big deal out of; they can just be who they are without having to prove a point.

So that was my starting point for that story, I just wanted to see what it was like to try and write a, like, micro-narrative that had more to do with the reader feeling like they were just hanging out at the beach with a bunch of Trans girls. And maybe within that, there was a small hint of romance, it just sort of leaks out, and the rest of it was more atmospheric. Still you get the sense that this is a community of Trans girls, but that’s not the reason [for the story], that’s not the narrative impulse. They’re multifaceted, and the story shows off some of that multiplicity of their characteristics.

HILOBROW: And it becomes a story of what would just naturally arise out of almost any group of people getting together and talking about romantic pursuits. It brings me back to… decades ago now, when Harvey Fierstein was on the original Letterman show, and Letterman said he didn’t remember two men kissing in some play Fierstein had out at the time, and Fierstein says, “Because love isn’t shocking.”

SOM: I also was interested in… I didn’t know how many conversations I could weave in there; I only have two, in that story, but they’re sort of cross conversations, they’re talking over each other. That’s something I’m interested in, in terms of showing the multiplicity of voices.

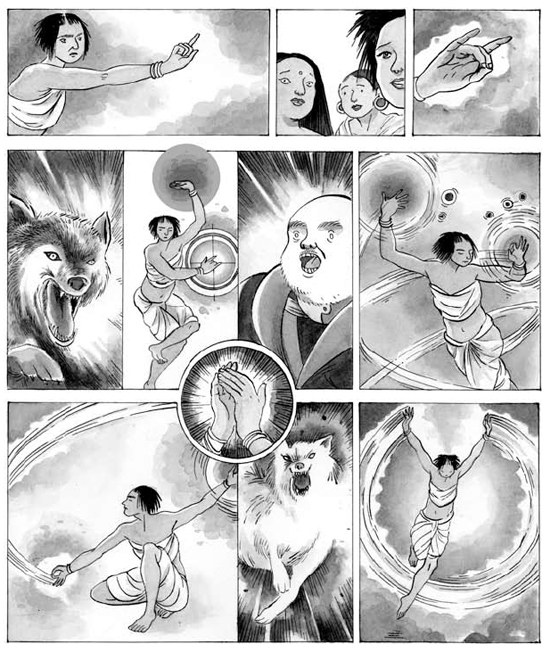

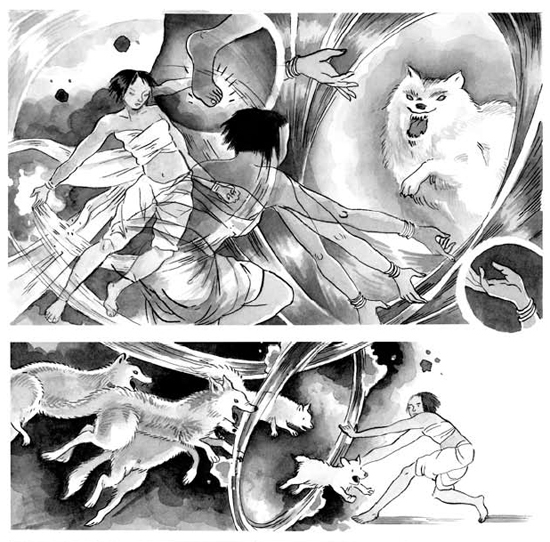

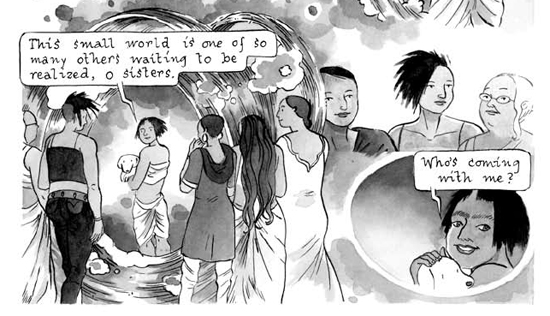

As for the Beyond story, I sort of had more of a mandate, as it were. This is Volume 2, and the theme for this one was post-apocalyptic and urban fantasy, so, I took that slightly loosely, I’m not sure which genre my story fits into…I guess it hints at a dystopia; that’s the reason why this community of South Asian Trans people are roaming the Earth and nomadic, and providing services, fertility services for everyone else. But I had to work more closely with the editors on that story, because, originally my story had a bit more hints of aggression and hostility, which I wanted to provide to show the kind of continuing sense of hostility that a lot of Trans people feel. But they also wanted me to tone it down a little bit, just… I think they thought there’s enough of that in the world, and these stories should be more positive. So I was trying to strike a balance between providing a context, the negative context against which all these characters are surviving and/or thriving, in the end, and having that negative context be not too in your face, or explicit, or aggressive.

HILOBROW: I think that turned out to be a good decision, because there was a really effective feeling of menace for me in that story, which may express even more the sense of threat that you were referring to — it hangs over the story and the characters, and it’s felt…if it had broken out into more literal violence, then that becomes something that a reader can spectate, whereas here, the reader is feeling the same dread, because, you’re waiting to see what happens, you’re dwelling inside the realm of what might possibly happen. I also felt… y’know, Jack Kirby called his fight scenes “brutal ballets,” and your story was mostly just the ballet, which I thought was very unusual.

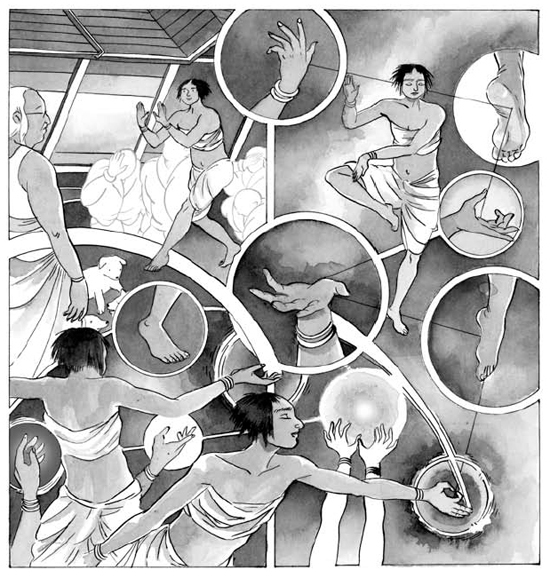

SOM: I had that very much in mind. I don’t know if you know about this, but the backstory is that South Asian Trans women, one word for them is “hijras,” and — it’s a multifaceted community, but sort of stereotypically, one way they make a living is by dancing and singing at weddings or births, things like this. They sort of impose themselves on these events, and — they’re feared, but also respected, so you have to give them money when they perform, because they’re considered auspicious. But also considered sort of suspect. That’s how they make their money. [So], in my story [they] use that sort of heritage, but magically turn that power of dance into a sort of force. And I very much had in mind things like Doctor Strange, like Steve Ditko’s otherworldly depictions of Doctor Strange and his magical powers, and the way he, the sort of acrobatics that he has to go through to perform those magical powers. It’s very much like a dance to me, and I found that very inspirational.

And also I’ve been working a lot on comics that incorporate dance as a motif or a theme. Originally the idea was, I was thinking of comics as a way of notating dance, being a record of choreography — that’s still in the back of my mind when I do stories like the one in Beyond, and one day I’d like to pursue that a little more explicitly.

HILOBROW: It certainly was very noticeable how the diagramming of dance lends itself to both the permanent nature and the kinetic illusion of comics. I thought that was a real breakthrough; the page design alone in that story, not to mention the lovely imagery, was a new plateau for your work in terms of the sense of motion, the way it almost seemed to be moving like a clockwork before my eyes though it’s a static page. Was there something in particular that made you turn to that as a subject and a model? I know you’ve been working with poets, have you been working with dancers?

SOM: I have not, but [Som’s life companion] Joan and I both love modern dance — I like modern dance; Joan also likes ballet, which I can’t stand. But I have been thinking a lot about choreography and how you make a record of it the way you write a score for music. I know there is a notation system for dance, but I was interested to know what comics could do in that realm. Also it was a nice fit with the topic, which was the way Trans people survive, or carve out a place in the world for themselves. And I wanted to use that trope of them being performers, and sort of turn it around, and make it not performance for the sake of being a spectacle, but rather performance as a tool of liberation [laughs].

HILOBROW: Disarming in more ways than one. [laughter] Is “hijra” a self-defining term or a slur?

SOM: I think a bit of both. It may have started as a slur but it’s been reclaimed, like “queer.”

HILOBROW: How far back does it go? I know that Native American cultures acknowledged multiple genders going back, I guess, millennia…

SOM: There’s mention of hijras in, I think even the Ramayana, which is an ancient text, and they’re said to have been some of the most fervent devotees of Rama, so, I think the myth is that, because they were such fervent devotees he conferred special powers on them. And that’s the origin of people believing they have certain abilities that cisgender or “normal” people don’t, that they’re considered to some degree divine and auspicious. The revulsion and hostility that they faced I think, is pretty much tied up with colonialism, and things like — I don’t know if you heard about the law that was just struck down, “377,” which was a vestige from colonial times, a very homophobic rule about criminalizing same-sex relationships. And that also applies indirectly and somewhat osmotically to the Trans community. These things are tied up with the legacy of the British in India, and them trying to impose their restrictions on an ancient culture, and then the sort of mish-mosh that comes out of that imposition.

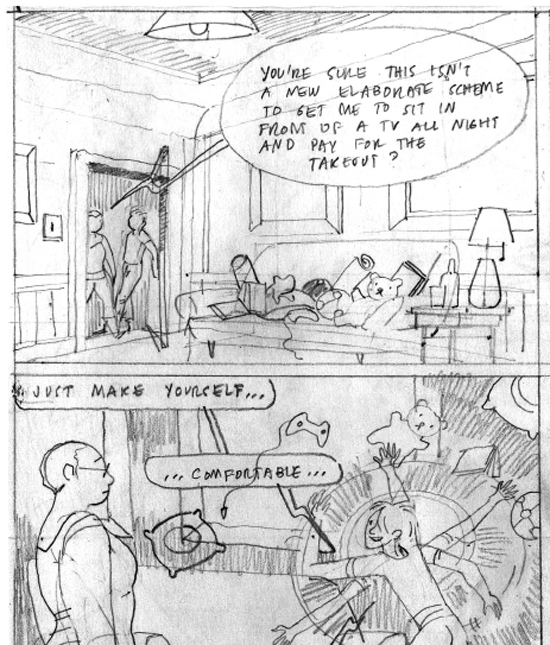

HILOBROW: I think homophobia was unknown in Native American communities until the arrival of missionaries and other such influences. Getting back to the dance motif, another thing that fascinated me about that is, especially in the Beyond story, it seems that there’s been an evolution in the sense of time, and movement through it, in your work. In the past, the reader’s eye would be directed around the page in certain ways, like a pair of characters being in different places on the same kind-of Mobius stairway, or there would be the use of insets to zoom in and out of scenes. Whereas you give more of a sense of simultaneity now, as with the whirling limbs of the dancer in the Beyond story or even the frenzied cleanup in the top-secret story that we’re doing. [laughter] It seemed to be the new standard for you, but then I read “Love Is Like a Cephalopod” and it has such a classic measured pace. So maybe you’re just expanding your repertoire?

SOM: The simultaneity in the Beyond II story was very specific to that story, so I’m not sure if I was thinking that was a new direction for me or not. But I’ve always been interested in depicting simultaneity within comics — what does Scott McCloud call it, “aspect to aspect”? — where within a scene you survey aspects of that scene without having to have narrative motion? I was interested in that, but interested also in having that not be restricted just to a simple panel breakdown where it’s a grid of panels, but rather to see how you can survey a scene or a moment and show that moment from multiple angles within a more organic panel layout — I don’t wanna say “panel” because that makes you think of little squares. I wanted to have it break loose from a grid or a strict panel layout, and have the page layout be part of the motion depicted within the story.

I’ve been trying to do that with other stories, but sometimes you need a bigger canvas to be able to do that, and while doing that I’ve also been trying to be a little more conventional. It’s liberating to be able to do that kind of work, where it’s more experimental, but lately I’ve been trying to restrain myself [laughs] and be a little more…direct, as far as storytelling goes. I feel as though I’ve been oscillating between those two poles.

HILOBROW: It’s almost like this tidal motion of moving forward while having a solid grounding to the work as well. There’s technically a conventionality to the cephalopod story, and yet it’s so…the way it tracks, you feel like you’re walking around the beach; the varying of focus and rotation of perspective gives a completeness and clarity of human experience. And there are things I haven’t seen you do before, like the way most of the backgrounds have no line at all, are just painted.

SOM: Yeah! That was a real challenge for me because as you know, I’m most comfortable with architectural — I don’t really think of them as backgrounds, but let’s just call them that — because that’s what I studied and what I’ve been drawing for most of my life: enclosed spaces, orthogonal lines, corners, edges, things like this. And then, part of the challenge that I set myself was, how do you depict an environment that has none of that. I also, like one of the characters in the story, I don’t like the beach. But the story is based to some degree on one summer when I did go to the beach, with a gaggle of Trans girls, and I knew I couldn’t convey that relying on my usual methods of like, architectural perspective or depicting a room the way I’m comfortable depicting a room. So to do it with just, depth, using tone, or shade, or to use more organic forms in the background, as the sort of backdrop, and still convey a sense of space, was kind of difficult for me. But I think I’d like to try more of that, just to expand my palette.

Images (top to bottom): An early cover to Som’s forthcoming graphic novel; detail from “Cephalopod”; detail from “Karana”; detail from Steve Ditko panel; detail from “Karana”; detail from “Karana”; detail from in-progress collaboration with this reporter; detail from “Cephalopod”; detail from “Karana”

Panel Zero logo designed by Steve Price

MORE COMICS-RELATED SERIES: Douglas Wolk’s LIMERICKANIA | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM — 25 writers on 25 Jack Kirby panels | ANNOTATED GIF — Kerry Callen brings comic book covers to life | COMICALLY VINTAGE — that’s-what-she-said vintage comic panels | DC — THE NEW 52 — an 11-year-old reviews DC’s new lineup | SECRET PANEL — Silver Age comics’ double entendres | SKRULLICISM — they lurk among us | Douglas Wolk’s THAT’S GREAT MARVEL, TAKING LIBERTIES, STERANKOISMS, MARVEL vs. MUSEUM, LIMERICKANIA, WTC WTF

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE