When the World Shook (22)

By:

August 3, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-second installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘At the appointed time which thou didst decree, I awoke again and found in my house strangers from another land. In the company of one of those whose spirit I drew forth, I visited the peoples of the new earth, and found them even baser and more evil than those whom I had known. Therefore, since they cannot be bettered. I purpose to destroy them also, and on their wreck to rebuild a glorious empire, such as was that of the Sons of Wisdom at its prime.'”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

Strangely enough, perhaps because of my mental exhaustion, for what I had passed through seemed to overwhelm me so that I could no longer so much as think with clearness, even after all that I have described I slept like a child and awoke refreshed and well.

I looked at my watch to find that it was now eight o’clock in the morning in this horrible place where there was neither morn, nor noon, nor night, but only an eternal brightness that came I knew not whence, and never learned.

I found that I was alone, since Bickley and Bastin had gone to fill our bottles with the Life-water. Presently they returned and we ate a little; with that water to drink one did not need much food. It was a somewhat silent meal, for our circumstances were a check on talk; moreover, I thought that the others looked at me rather oddly. Perhaps they guessed something of my midnight visit to the temple, but if so they thought it wisest to say nothing. Nor did I enlighten them.

Shortly after we had finished Yva appeared. She was wonderfully quiet and gentle in her manner, calm also, and greeted all of us with much sweetness. Of our experiences during the night she said no word to me, even when we were alone. One difference I noticed about her, however; that she was clothed in garments such as I had never seen her wear before. They were close fitting, save for a flowing cape, and made of some grey material, not unlike a coarse homespun or even asbestos cloth. Still they became her very well, and when I remarked upon them, all she answered was that part of our road would be rough. Even her feet were shod with high buskins of this grey stuff.

Presently she touched Bastin on the shoulder and said that she would speak with him apart. They went together into one of the chambers of that dwelling and there remained for perhaps the half of an hour. It was towards the end of this time that in the intense silence I heard a crash from the direction of the temple, as though something heavy had fallen to the rocky floor. Bickley also heard this sound. When the two reappeared I noticed that though still quite calm, Yva looked radiant, and, if I may say so, even more human and womanly than I had ever seen her, while Bastin also seemed very happy.

“One has strange experiences in life, yes, very strange,” he remarked, apparently addressing the air, which left me wondering to what particular experience he might refer. Well, I thought that I could guess.

“Friends,” said Yva, “it is time for us to be going and I am your guide. You will meet the Lord Oro at the end of your journey. I pray you to bring those lamps of yours with you, since all the road is not lightened like this place.”

“I should like to ask,” said Bickley, “whither we go and for what object, points on which up to the present we have had no definite information.”

“We go, friend Bickley, deep into the bowels of the world, far deeper, I think, than any mortal men have gone hitherto, that is, of your race.”

“Then we shall perish of heat,” said Bickley, “for with every thousand feet the temperature rises many degrees.”

“Not so. You will pass through a zone of heat, but so swiftly that if you hold your breath you will not suffer overmuch. Then you will come to a place where a great draught blows which will keep you cool, and thence travel on to the end.”

“Yes, but to what end, Lady Yva?”

“That you will see for yourselves, and with it other wondrous things.”

Here some new idea seemed to strike her, and after a little hesitation she added:

“Yet why should you go? Oro has commanded it, it is true, but I think that at the last he will forget. It must be decided swiftly. There is yet time. I can place you in safety in the sepulchre of Sleep where you found us. Thence cross to the main island and sail away quickly in your boat out into the great sea, where I believe you will find succour. Know that after disobeying him, you must meet Oro no more lest it should be the worse for you. If that be your will, let us start. What say you?”

She looked at me.

“I say, Yva, that I am willing to go if you come with us. Not otherwise.”

“I say,” said Bickley, “that I want to see all this supernatural rubbish thoroughly exploded, and that therefore I should prefer to go on with the business.”

“And I say,” said Bastin, “that my most earnest desire is to be clear of the whole thing, which wearies and perplexes me more than I can tell. Only I am not going to run away, unless you think it desirable to do so too, Lady Yva. I want you to understand that I am not in the least afraid of the Lord Oro, and do not for one moment believe that he will be allowed to bring about disaster to the world, as I understand is his wicked object. Therefore on the whole I am indifferent and quite prepared to accept any decision at which the rest of you may arrive.”

“Be it understood,” said Yva with a little smile when Bastin had finished his sermonette, “that I must join my father in the bowels of the earth for a reason which will be made plain afterwards. Therefore, if you go we part, as I think to meet no more. Still my advice is that you should go.” [*]

[ * It is fortunate that we did not accept Yva’s offer. Had we done so we should have found ourselves shut in, and perished, as shall be told.—H. A. ]

To this our only answer was to attend to the lighting of our lamps and the disposal of our small impedimenta, such as our tins of oil and water bottles. Yva noted this and laughed outright.

“Courage did not die with the Sons of Wisdom,” she said.

Then we set out, Yva walking ahead of us and Tommy frisking at her side.

Our road led us through the temple. As we passed the great gates I started, for there, in the centre of that glorious building, I perceived a change. The statue of Fate was no more! It lay broken upon the pavement among those fragments of its two worshippers which I had seen shaken down some hours before.

“What does this mean?” I whispered to Yva. “I have felt no other earthquake.”

“I do not know,” she answered, “or if I know I may not say. Yet learn that no god can live on without a single worshipper, and, in a fashion, that idol was alive, though this you will not believe.”

“How very remarkable,” said Bastin, contemplating the ruin. “If I were superstitious, which I am not, I should say that this occurrence was an omen indicating the final fall of a false god. At any rate it is dead now, and I wonder what caused it?”

“I felt an earth tremor last night,” said Bickley, “though it is odd that it should only have affected this particular statue. A thousand pities, for it was a wonderful work of art.”

Then I remembered and reminded Bickley of the crash which we had heard while Yva and Bastin were absent on some secret business in the chamber.

Walking the length of the great church, if so it could be called, we came to an apse at the head of it where, had it been Christian, the altar would have stood. In this apse was a little open door through which we passed. Beyond it lay a space of rough rock that looked as though it had been partially prepared for the erection of buildings and then abandoned. All this space was lighted, however, like the rest of the City of Nyo, and in the same mysterious way. Led by Yva, we threaded our path between the rough stones, following a steep downward slope. Thus we walked for perhaps half a mile, till at length we came to the mouth of a huge pit that must, I imagine, have lain quite a thousand feet below the level of the temple.

I looked over the edge of this pit and shrank back terrified. It seemed to be bottomless. Moreover, a great wind rushed up it with a roaring sound like to that of an angry sea. Or rather there were two winds, perhaps draughts would be a better term, if I may apply it to an air movement of so fierce and terrible a nature. One of these rushed up the pit, and one rushed down. Or it may have been that the up rush alternated with the down rush. Really it is impossible to say.

“What is this place?” I asked, clinging to the others and shrinking back in alarm from its sheer edge and bottomless depth, for that this was enormous we could see by the shaft of light which flowed downwards farther than the eye could follow.

“It is a vent up and down which air passes from and to the central hollows of the earth,” Yva answered. “Doubtless in the beginning through it travelled that mighty force which blew out these caves in the heated rocks, as the craftsman blows out glass.”

“I understand,” said Bastin. “Just like one blows out a bubble on a pipe, only on a larger scale. Well, it is very interesting, but I have seen enough of it. Also I am afraid of being blown away.”

“I fear that you must see more,” answered Yva with a smile, “since we are about to descend this pit.”

“Do you mean that we are to go down that hole, and if so, how? I don’t see any lift, or moving staircase, or anything of that sort.”

“Easily and safely enough, Bastin. See.”

As she spoke a great flat rock of the size of a small room appeared, borne upwards, as I suppose, by the terrific draught which roared past us on its upward course. When it reached the lip of the shaft, it hung a little while, then moved across and began to descend with such incredible swiftness that in a few seconds it had vanished from view.

“Oh!” said Bastin, with his eyes almost starting out of his head, “that’s the lift, is it? Well, I tell you at once I don’t like the look of the thing. It gives me the creeps. Suppose it tilted.”

“It does not tilt,” answered Yva, still smiling. “I tell you, Bastin, that there is naught to fear. Only yesterday, I rode this rock and returned unharmed.”

“That is all very well, Lady Yva, but you may know how to balance it; also when to get on and off.”

“If you are afraid, Bastin, remain here until your companions return. They, I think, will make the journey.”

Bickley and I intimated that we would, though to tell the truth, if less frank we were quite as alarmed as Bastin.

“No, I’ll come too. I suppose one may as well die this way as any other, and if anything were to happen to them and I were left alone, it would be worse still.”

“Then be prepared,” said Yva, “for presently this air-chariot of ours will return. When it appears and hangs upon the edge, step on to it and throw yourselves upon your faces and all will be well. At the foot of the shaft the motion lessens till it almost stops, and it is easy to spring, or even crawl to the firm earth.”

Then she stooped down and lifted Tommy who was sniffing suspiciously at the edge of the pit, his long ears blown straight above his head, holding him beneath her left arm and under her cloak, that he might not see and be frightened.

We waited a while in silence, perhaps for five or six minutes, among the most disagreeable, I think, that I ever passed. Then far down in the brightness below appeared a black speck that seemed to grow in size as it rushed upwards.

“It comes,” said Yva. “Prepare and do as I do. Do not spring, or run, lest you should go too far. Step gently on to the rock and to its centre, and there lie down. Trust in me, all of you.”

“There’s nothing else to do,” groaned Bastin.

The great stone appeared and, as before, hung at the edge of the pit. Yva stepped on to it quietly, as she did so, catching hold of my wrist with her disengaged hand. I followed her feeling very sick, and promptly sat down. Then came Bickley with the air of the virtuous hero of a romance walking a pirate’s plank, and also sat down. Only Bastin hesitated until the stone began to move away. Then with an ejaculation of “Here goes!” he jumped over the intervening crack of space and landed in the middle of us like a sack of coal. Had I not been seated really I think he would have knocked me off the rock. As it was, with one hand he gripped me by the beard and with the other grasped Yva’s robe, of neither of which would he leave go for quite a long time, although we forced him on to his face. The lantern which he held flew from his grasp and descended the shaft on its own account.

“You silly fool!” exclaimed Bickley whose perturbation showed itself in anger. “There goes one of our lamps.”

“Hang the lamp!” muttered the prostrate Bastin. “We shan’t want it in Heaven, or the other place either.”

Now the stone which had quivered a little beneath the impact of Bastin, steadied itself again and with a slow and majestic movement sailed to the other side of the gulf. There it felt the force of gravity, or perhaps the weight of the returning air pressed on it, which I do not know. At any rate it began to fall, slowly at first, then more swiftly, and afterwards at an incredible pace, so that in a few seconds the mouth of the pit above us grew small and presently vanished quite away. I looked up at Yva who was standing composedly in the midst of our prostrate shapes. She bent down and called in my ear:

“All is well. The heat begins, but it will not endure for long.”

I nodded and glanced over the edge of the stone at Bastin’s lantern which was sailing alongside of us, till presently we passed it. Bastin had lit it before we started, I think in a moment of aberration, and it burned for quite a long while, showing like a star when the shaft grew darker as it did by degrees, a circumstance that testifies to the excellence of the make, which is one advertised not to go out in any wind. Not that we felt wind, or even draught, perhaps because we were travelling with it.

Then we entered the heat zone. About this there was no doubt, for the perspiration burst out all over me and the burning air scorched my lungs. Also Tommy thrust his head from beneath the cloak with his tongue hanging out and his mouth wide open.

“Hold your breaths!” cried Yva, and we obeyed until we nearly burst. At least I did, but what happened to the others I do not know.

Fortunately it was soon over and the air began to grow cool again. By now we had travelled an enormous distance, it seemed to be miles on miles, and I noticed that our terrific speed was slackening, also that the shaft grew more narrow, till at length there were only a few feet between the edge of the stone and its walls. The result of this, or so I supposed, was that the compressed air acted as a buffer, lessening our momentum, till at length the huge stone moved but very slowly.

“Be ready to follow me,” cried Yva again, and we rose to our feet, that is, Bickley and I did, but poor Bastin was semi-comatose. The stone stopped and Yva sprang from it to a rock platform level with which it lay. We followed, dragging Bastin between us. As we did so something hit me gently on the head. It was Bastin’s lamp, which I seized.

“We are safe. Sit down and rest,” said Yva, leading us a few paces away.

We obeyed and presently by the dim light saw the stone begin to stir again, this time upwards. In another twenty seconds it was away on its never-ending journey.

“Does it always go on like that?” said Bastin, sitting up and staring after it.

“Tens of thousands of years ago it was journeying thus, and tens of thousands of years hence it will still be journeying, or so I think,” she replied. “Why not, since the strength of the draught never changes and there is nothing to wear it except the air?”

Somehow the vision of this huge stone, first loosed and set in motion by heaven knows what agency, travelling from aeon to aeon up and down that shaft in obedience to some law I did not understand, impressed my imagination like a nightmare. Indeed I often dream of it to this day.

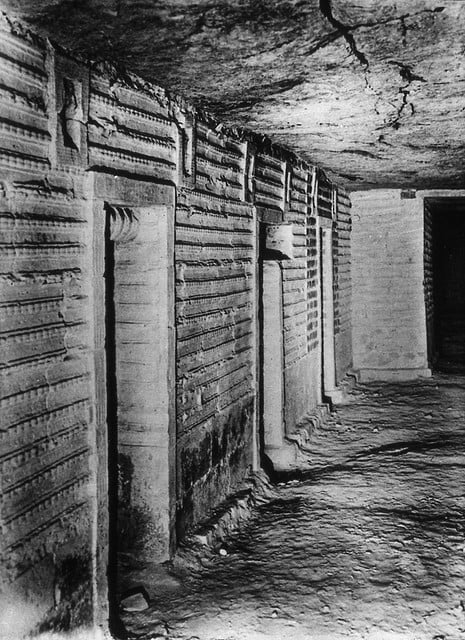

I looked about me. We were in some cavernous place that could be but dimly seen, for here the light that flowed down the shaft from the upper caves where it was mysteriously created, scarcely shone, and often indeed was entirely cut off, when the ever-journeying stone was in the narrowest parts of the passage. I could see, however, that this cavern stretched away both to right and left of us, while I felt that from the left, as we sat facing the shaft, there drew down a strong blast of fresh air which suggested that somewhere, however far away, it must open on to the upper world. For the rest its bottom and walls seemed to be smooth as though they had been planed in the past ages by the action of cosmic forces. Bickley noticed this the first and pointed it out to me. We had little time to observe, however, for presently Yva said:

“If you are rested, friends, I pray you light those lamps of yours, since we must walk a while in darkness.”

We did and started, still travelling downhill. Yva walked ahead with me and Tommy who seemed somewhat depressed and clung close to our heels. The other two followed, arguing strenuously about I know not what. It was their way of working off irritation and alarms.

I asked Yva what was about to happen, for a great fear oppressed me.

“I am not sure, Beloved,” she answered in a sweet and gentle voice, “who do not know all Oro’s secrets, but as I think, great things. We are now deep in the bowels of the world, and presently, perhaps, you will see some of its mighty forces whereof your ignorant races have no knowledge, doing their everlasting work.”

“Then how is it that we can breathe here?” I asked.

“Because this road that we are following connects with the upper air or used to do so, since once I followed it. It is a long road and the climb is steep, but at last it leads to the light of the blessed sun, nor are there any pitfalls in the path. Would that we might tread it together, Humphrey,” she added with passion, “and be rid of mysteries and the gloom, or that light which is worse than gloom.”

“Why not?” I asked eagerly. “Why should we not turn and flee?”

“Who can flee from my father, the Lord Oro?” she replied. “He would snare us before we had gone a mile. Moreover, if we fled, by tomorrow half the world must perish.”

“And how can we save it by not flying, Yva?”

“I do not know, Humphrey, yet I think it will be saved, perchance by sacrifice. That is the keystone of your faith, is it not? Therefore if it is asked of you to save the world, you will not shrink from it, will you, Humphrey?”

“I hope not,” I replied, without enthusiasm, I admit. Indeed it struck me that a business of this sort was better fitted to Bastin than to myself, or at any rate to his profession. I think she guessed my thoughts, for by the light of the lamp I saw her smile in her dazzling way. Then after a swift glance behind her, she turned and suddenly kissed me, as she did so calling down everlasting blessings on my head and on my spirit. There was something very wonderful about this benediction of Yva’s and it thrilled me through and through, so that to it I could make no answer.

Next moment it was too late to retreat, for our narrowing passage turned and we found ourselves in a wondrous place. I call it wondrous because of it we could see neither the beginning nor the end, nor the roof, nor aught else save the rock on which we walked, and the side or wall that our hands touched. Nor was this because of darkness, since although it was not illuminated like the upper caverns, light of a sort was present. It was a very strange light, consisting of brilliant and intermittent flashes, or globes of blue and lambent flame which seemed to leap from nowhere into nowhere, or sometimes to hang poised in mid air.

“How odd they are,” said the voice of Bastin behind me. “They remind me of those blue sparks which jump up from the wires of the tramways in London on a dark night. You know, don’t you, Bickley? I mean when the conductor pulls round that long stick with an iron wheel on the top of it.”

“Nobody but you could have thought of such a comparison, Bastin,” answered Bickley. “Still, multiplied a thousandfold they are not unlike.”

Nor indeed were they, except that each blue flash was as big as the full moon and in one place or another they were so continuous that one could have read a letter by their light. Also the effect of them was ghastly and most unnatural, terrifying, too, since even their brilliance could not reveal the extent of that gigantic hollow in the bowels of the world wherein they leapt to and fro like lightnings, or hung like huge, uncanny lanterns.

SACRIFICE

“The air in this place must be charged with some form of electricity, but the odd thing is that it does not seem to harm us,” said Bickley in a matter-of-fact fashion as though he were determined not to be astonished.

“To me it looks more like marsh fires or St. Elmo lights, though how these can be where there is no vapour, I do not know,” I answered.

As I spoke a particularly large ball of flame fell from above. It resembled a shooting star or a meteor more than anything else that I had ever seen, and made me wonder whether we were not perhaps standing beneath some inky, unseen sky.

Next moment I forgot such speculations, for in its blue light, which made him terrible and ghastly, I perceived Oro standing in front of us clad in a long cloak.

“Dear me!” said Bastin, “he looks just like the devil, doesn’t he, and now I come to think of it, this isn’t at all a bad imitation of hell.”

“How do you know it is an imitation?” asked Bickley.

“Because whatever might be the case with you, Bickley, if it were, the Lady Yva and I should not be here.”

Even then I could not help smiling at this repartee, but the argument went no further for Oro held up his hand and Yva bent the knee in greeting to him.

“So you have come, all of you,” he said. “I thought that perhaps there were one or two who would not find courage to ride the flying stone. I am glad that it is not so, since otherwise he who had shown himself a coward should have had no share in the rule of that new world which is to be. Therefore I chose yonder road that it might test you.”

“Then if you will be so good as to choose another for us to return by, I shall be much obliged to you, Oro,” said Bastin.

“How do you know that if I did it would not be more terrible, Preacher? How do you know indeed that this is not your last journey from which there is no return?”

“Of course I can’t be sure of anything, Oro, but I think the question is one which you might more appropriately put to yourself. According to your own showing you are now extremely old and therefore your end is likely to come at any moment. Of course, however, if it did you would have one more journey to make, but it wouldn’t be polite for me to say in what direction.”

Oro heard, and his splendid, icy face was twisted with sudden rage. Remembering the scene in the temple where he had grovelled before his god, uttering agonised, unanswered prayers for added days, I understood the reason of his wrath. It was so great that I feared lest he should kill Bastin (who only a few hours before, be it remembered, had tried to kill him) then and there, as doubtless he could have done if he wished. Fortunately, if he felt it; the impulse passed.

“Miserable fool!” he said. “I warn you to keep a watch upon your words. Yesterday you would have slain me with your toy. Today you stab me with your ill-omened tongue. Be fearful lest I silence it for ever.”

“I am not in the least fearful, Oro, since I am sure that you can’t hurt me at all any more than I could hurt you last night because, you see, it wasn’t permitted. When the time comes for me to die, I shall go, but you will have nothing to do with that. To tell the truth, I am very sorry for you, as with all your greatness, your soul is of the earth, earthy, also sensual and devilish, as the Apostle said, and, I am afraid, very malignant, and you will have a great deal to answer for shortly. Yours won’t be a happy deathbed, Oro, because, you see, you glory in your sins and don’t know what repentance means.”

I must add that when I heard these words I was filled with the most unbounded admiration for Bastin’s fearless courage which enabled him thus to beard this super-tyrant in his den. So indeed were we all, for I read it in Yva’s face and heard Bickley mutter:

“Bravo! Splendid! After all there is something in faith!”

Even Oro appreciated it with his intellect, if not with his heart, for he stared at the man and made no answer. In the language of the ring, he was quite “knocked out” and, almost humbly, changed the subject.

“We have yet a little while,” he said, “before that happens which I have decreed. Come, Humphrey, that I may show you some of the marvels of this bubble blown in the bowels of the world,” and he motioned to us to pick up the lanterns.

Then he led us away from the wall of the cavern, if such it was, for a distance of perhaps six or seven hundred paces. Here suddenly we came to a great groove in the rocky floor, as broad as a very wide roadway, and mayhap four feet in depth. The bottom of this groove was polished and glittered; indeed it gave us the impression of being iron, or other ore which had been welded together beneath the grinding of some immeasurable weight. Just at the spot where we struck the groove, it divided into two, for this reason.

In its centre the floor of iron, or whatever it may have been, rose, the fraction of an inch at first, but afterwards more sharply, and this at a spot where the groove had a somewhat steep downward dip which appeared to extend onwards I know not how far.

Following along this central rise for a great way, nearly a mile, I should think, we observed that it became ever more pronounced, till at length it ended in a razor-edge cliff which stretched up higher than we could see, even by the light of the electrical discharges. Standing against the edge of this cliff, we perceived that at a distance from it there were now two grooves of about equal width. One of these ran away into the darkness on our right as we faced the sharp edge, and at an ever-widening angle, while the other, at a similar angle, ran into the darkness to the left of the knife of cliff. That was all.

NEXT WEEK: “‘Once in the dead days I turned the balance of the world from the right-hand road which now is dull with disuse, to the left-hand road which glitters so brightly to your eyes, and the face of the earth was changed. Now again I will turn it from the left-hand road to the right-hand road in which for millions of years it was wont to run, and once more the face of the earth shall change, and those who are left living upon the earth, or who in the course of ages shall come to live upon the new earth, must bow down to Oro and take him and his seed to be their gods and kings.'”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.