When the World Shook (9)

By:

May 4, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the ninth installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Look,’ said Bickley, holding up his candle, ‘and tell me — what’s that?’ Before me, faintly shown, was some curious structure of gleaming rods made of yellowish metal, which rods appeared to be connected by wires. The structure might have been forty feet high and perhaps a hundred long. Its bottom part was buried in dust.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

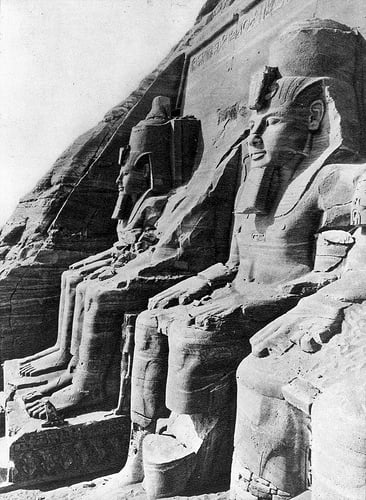

We went straight to the statue, although Bickley passed the half-buried machines with evident regret. As we had hoped, the strong light of the rising sun fell upon it in a vivid ray, revealing all its wondrous workmanship and the majesty — for no other word describes it — of the somewhat terrifying countenance that appeared above the wrappings of the shroud. Indeed, I was convinced that originally this monument had been placed here in order that on certain days of the year the sun might fall upon it thus, when probably worshippers assembled to adore their hallowed symbol. After all, this was common in ancient days: witness the instance of the awful Three who sit in the deepest recesses of the temple of Abu Simbel, on the Nile.

We gazed and gazed our fill, at least Bickley and I did, for Bastin was occupied in making a careful comparison between the head of his wooden Oro and that of the statue.

“There is no doubt that they are very much alike,” he said. “Why, whatever is that dog doing? I think it is going mad,” and he pointed to Tommy who was digging furiously at the base of the lowest step, as at home I have seen him do at roots that sheltered a rabbit.

Tommy’s energy was so remarkable that at length it seriously attracted our attention. Evidently he meant that it should do so, for occasionally he sprang back to me barking, then returned and sniffed and scratched. Bickley knelt down and smelt at the stone.

“It is an odd thing, Humphrey,” he said, “but there is a strange odour here, a very pleasant odour like that of sandal-wood or attar of roses.”

“I never heard of a rat that smelt like sandal-wood or attar of roses,” said Bastin. “Look out that it isn’t a snake.”

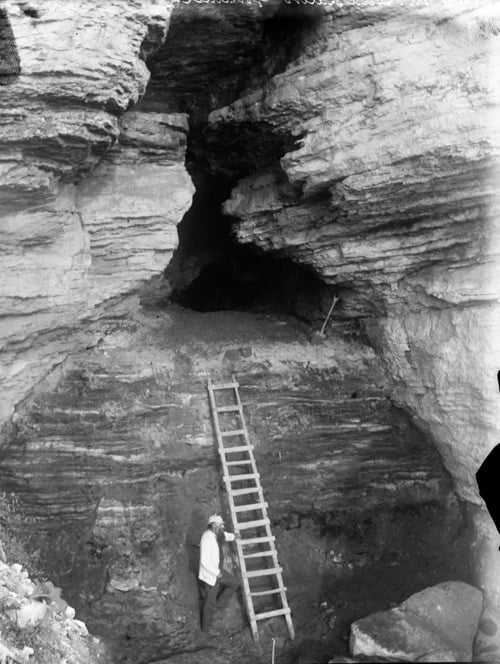

I knelt down beside Bickley, and in clearing away the deep dust from what seemed to be the bottom of the step, which was perhaps four feet in height, by accident thrust my amateur spade somewhat strongly against its base where it rested upon the rocky floor.

Next moment a wonder came to pass. The whole massive rock began to turn outwards as though upon a pivot! I saw it coming and grabbed Bickley by the collar, dragging him back so that we just rolled clear before the great block, which must have weighed several tons, fell down and crushed us. Tommy saw it too, and fled, though a little late, for the edge of the block caught the tip of his tail and caused him to emit a most piercing howl. But we did not think of Tommy and his woes; we did not think of our own escape or of anything else because of the marvel that appeared to us. Seated there upon the ground, after our backward tumble, we could see into the space which lay behind the fallen step, for there the light of the sun penetrated.

The first idea it gave me was that of the jewelled shrine of some mediaeval saint which, by good fortune, had escaped the plunderers; there are still such existing in the world. It shone and glittered, apparently with gold and diamonds, although, as a matter of fact, there were no diamonds, nor was it gold which gleamed, but some ancient metal, or rather amalgam, which is now lost to the world, the same that was used in the tubes of the air-machines. I think that it contained gold, but I do not know. At any rate, it was equally lasting and even more beautiful, though lighter in colour.

For the rest this adorned recess which resembled that of a large funeral vault, occupying the whole space beneath the base of the statue that was supported on its arch, was empty save for two flashing objects that lay side by side but with nearly the whole width of the vault between them.

I pointed at them to Bickley with my finger, for really I could not speak.

“Coffins, by Jove!” he whispered. “Glass or crystal coffins and people in them. Come on!”

A few seconds later we were crawling into that vault while Bastin, still nursing the head of Oro as though it were a baby, stood confused outside muttering something about desecrating hallowed graves.

Just as we reached the interior, owing to the heightening of the sun, the light passed away, leaving us in a kind of twilight. Bickley produced carriage candles from his pocket and fumbled for matches. While he was doing so I noticed two things — firstly, that the place really did smell like a scent-shop, and, secondly, that the coffins seemed to glow with a kind of phosphorescent light of their own, not very strong, but sufficient to reveal their outlines in the gloom. Then the candles burnt up and we saw.

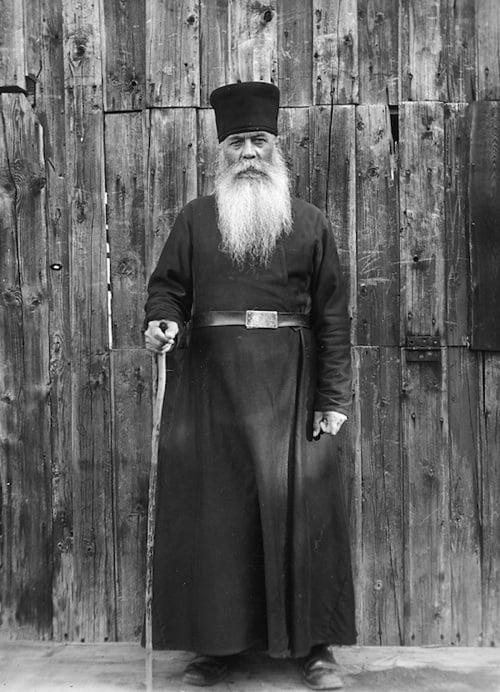

Within the coffin that stood on our left hand as we entered, for this crystal was as transparent as plate glass, lay a most wonderful old man, clad in a gleaming, embroidered robe. His long hair, which was parted in the middle, as we could see beneath the edge of the pearl-sewn and broidered cap he wore, also his beard were snowy white. The man was tall, at least six feet four inches in height, and rather spare. His hands were long and thin, very delicately made, as were his sandalled feet.

But it was his face that fixed our gaze, for it was marvelous, like the face of a god, and, as we noticed at once, with some resemblance to that of the statue above. Thus the brow was broad and massive, the nose straight and long, the mouth stern and clear-cut, while the cheekbones were rather high, and the eyebrows arched. Such are the characteristics of many handsome old men of good blood, and as the mummies of Seti and others show us, such they have been for thousands of years. Only this man differed from all others because of the fearful dignity stamped upon his features. Looking at him I began to think at once of the prophet Elijah as he must have appeared rising to heaven, enhanced by the more earthly glory of Solomon, for although the appearance of these patriarchs is unknown, of them one conceives ideas. Only it seemed probable that Elijah may have looked more benign. Here there was no benignity, only terrible force and infinite wisdom.

Contemplating him I shivered a little and felt thankful that he was dead. For to tell the truth I was afraid of that awesome countenance which, I should add, was of the whiteness of paper, although the cheeks still showed tinges of colour, so perfect was the preservation of the corpse.

I was still gazing at it when Bickley said in a voice of amazement:

“I say, look here, in the other coffin.”

I turned, looked, and nearly collapsed on the floor of the vault, since beauty can sometimes strike us like a blow. Oh! there before me lay all loveliness, such loveliness that there burst from my lips an involuntary cry:

“Alas! that she should be dead!”

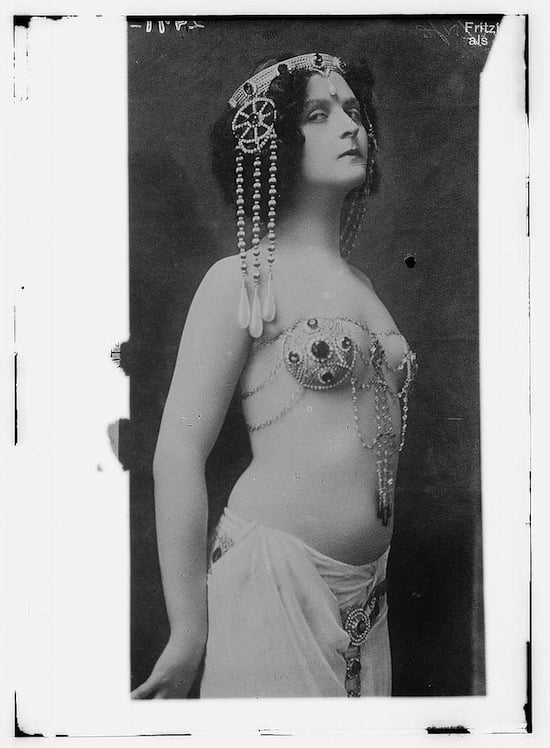

A young woman, I supposed, at least she looked young, perhaps five or six and twenty years of age, or so I judged. There she lay, her tall and delicate shape half hidden in masses of rich-hued hair in colour of a ruddy blackness. I know not how else to describe it, since never have I seen any of the same tint. Moreover, it shone with a life of its own as though it had been dusted with gold. From between the masses of this hair appeared a face which I can only call divine. There was every beauty that woman can boast, from the curving eyelashes of extraordinary length to the sweet and human mouth. To these charms also were added a wondrous smile and an air of kind dignity, very different from the fierce pride stamped upon the countenance of the old man who was her companion in death.

She was clothed in some close-fitting robe of white broidered with gold; pearls were about her neck, lying far down upon the perfect bosom, a girdle of gold and shining gems encircled her slender waist, and on her little feet were sandals fastened with red stones like rubies. In truth, she was a splendid creature, and yet, I know not how, her beauty suggested more of the spirit than of the flesh. Indeed, in a way, it was unearthly. My senses were smitten, it pulled at my heart-strings, and yet its unutterable strangeness seemed to awake memories within me, though of what I could not tell. A wild fancy came to me that I must have known this heavenly creature in some past life.

By now Bastin had joined us, and, attracted by my exclamation and by the attitude of Bickley, who was staring down at the coffin with a fixed look upon his face, not unlike that of a pointer when he scents game, he began to contemplate the wonder within it in his slow way.

“Well, I never!” he said. “Do you think the Glittering Lady in there is human?”

“The Glittering Lady is dead, but I suppose that she was human in her life,” I answered in an awed whisper.

“Of course she is dead, otherwise she would not be in that glass coffin. I think I should like to read the Burial Service over her, which I daresay was never done when she was put in there.”

“How do you know she is dead?” asked Bickley in a sharp voice and speaking for the first time. “I have seen hundreds of corpses, and mummies too, but never any that looked like these.”

I stared at him. It was strange to hear Bickley, the scoffer at miracles, suggesting that this greatest of all miracles might be possible.

“They must have been here a long time,” I said, “for although human, they are not, I think, of any people known to the world to-day; their dress, everything, shows it, though perhaps thousands of years ago —” and I stopped.

“Quite so,” answered Bickley; “I agree. That is why I suggest that they may have belonged to a race who knew what we do not, namely, how to suspend animation for great periods of time.”

I said no more, nor did Bastin, who was now engaged in studying the old man, and for once, wonderstruck and overcome. Bickley, however, took one of the candles and began to make a close examination of the coffins. So did Tommy, who sniffed along the join of that of the Glittering Lady until his nose reached a certain spot, where it remained, while his black tail began to wag in a delighted fashion. Bickley pushed him away and investigated.

“As I thought,” he said —”air-holes. See!”

I looked, and there, bored through the crystal of the coffin in a line with the face of its occupant, were a number of little holes that either by accident or design outlined the shape of a human mouth.

“They are not airtight,” murmured Bickley; “and if air can enter, how can dead flesh remain like that for ages?”

Then he continued his search upon the other side.

“The lid of this coffin works on hinges,” he said. “Here they are, fashioned of the crystal itself. A living person within could have pulled it down before the senses departed.”

“No,” I answered; “for look, here is a crystal bolt at the end and it is shot from without.”

This puzzled him; then as though struck by an idea, he began to examine the other coffin.

“I’ve got it!” he exclaimed presently. “The old god in here” (somehow we all thought of this old man as not quite normal) “shut down the Glittering Lady’s coffin and bolted it. His own is not bolted, although the bolt exists in the same place. He just got in and pulled down the lid. Oh! what nonsense I am talking — for how can such things be? Let us get out and think.”

So we crept from the sepulchre in which the perfumed air had begun to oppress us and sat ourselves down upon the floor of the cave, where for a while we remained silent.

“I am very thirsty,” said Bastin presently. “Those smells seem to have dried me up. I am going to get some tea —I mean water, as unfortunately there is no tea,” and he set off towards the mouth of the cave.

We followed him, I don’t quite know why, except that we wished to breathe freely outside, also we knew that the sepulchre and its contents would be as safe as they had been for — well, how long?

It proved to be a beautiful morning outside. We walked up and down enjoying it sub-consciously, for really our — that is Bickley’s and my own — intelligences were concentrated on that sepulchre and its contents. Where Bastin’s may have been I do not know, perhaps in a visionary teapot, since I was sure that it would take him a day or two to appreciate the significance of our discoveries. At any rate, he wandered off, making no remarks about them, to drink water, I suppose.

Presently he began to shout to us from the end of the table-rock and we went to see the reason of his noise. It proved to be very satisfactory, for while we were in the cave the Orofenans had brought absolutely everything belonging to us, together with a large supply of food from the main island. Not a single article was missing; even our books, a can with the bottom out, and the broken pieces of a little pocket mirror had been religiously transported, and with these a few articles that had been stolen from us, notably my pocket-knife. Evidently a great taboo had been laid upon all our possessions. They were now carefully arranged in one of the grooves of the rock that Bickley supposed had been made by the wheels of aeroplanes, which was why we had not seen them at once.

Each of us rushed for what we desired most —Bastin for one of the canisters of tea, I for my diaries, and Bickley for his chest of instruments and medicines. These were removed to the mouth of the cave, and after them the other things and the food; also a bell tent and some camp furniture that we had brought from the ship. Then Bastin made some tea of which he drank four large pannikins, having first said grace over it with unwonted fervour. Nor did we disdain our share of the beverage, although Bickley preferred cocoa and I coffee. Cocoa and coffee we had no time to make then, and in view of that sepulchre in the cave, what had we to do with cocoa and coffee?

So Bickley and I said to each other, and yet presently he changed his mind and in a special metal machine carefully made some extremely strong black coffee which he poured into a thermos flask, previously warmed with hot water, adding thereto about a claret glass of brandy. Also he extracted certain drugs from his medicine-chest, and with them, as I noted, a hypodermic syringe, which he first boiled in a kettle and then shut up in a little tube with a glass stopper.

These preparations finished, he called to Tommy to give him the scraps of our meal. But there was no Tommy. The dog was missing, and though we hunted everywhere we could not find him. Finally we concluded that he had wandered off down the beach on business of his own and would return in due course. We could not bother about Tommy just then.

After making some further preparations and fidgeting about a little, Bickley announced that as we had now some proper paraffin lamps of the powerful sort which are known as “hurricane,” he proposed by their aid to carry out further examinations in the cave.

“I think I shall stop where I am,” said Bastin, helping himself from the kettle to a fifth pannikin of tea. “Those corpses are very interesting, but I don’t see any use in staring at them again at present. One can always do that at any time. I have missed Marama once already by being away in that cave, and I have a lot to say to him about my people; I don’t want to be absent in case he should return.”

“To wash up the things, I suppose,” said Bickley with a sniff; “or perhaps to eat the tea-leaves.”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I have noticed that these natives have a peculiar taste for tea-leaves. I think they believe them to be a medicine, but I don’t suppose they would come so far for them, though perhaps they might in the hope of getting the head of Oro. Anyhow, I am going to stop here.”

“Pray do,” said Bickley. “Are you ready, Humphrey?”

I nodded, and he handed to me a felt-covered flask of the non-conducting kind, filled with boiling water, a tin of preserved milk, and a little bottle of meat extract of a most concentrated sort. Then, having lit two of the hurricane lamps and seen that they were full of oil, we started back up the cave.

RESURRECTION

We reached the sepulchre without stopping to look at the parked machines or even the marvelous statue that stood above it, for what did we care about machines or statues now? As we approached we were astonished to hear low and cavernous growlings.

“There is some wild beast in there,” said Bickley, halting. “No, by George! it’s Tommy. What can the dog be after?”

We peeped in, and there sure enough was Tommy lying on the top of the Glittering Lady’s coffin and growling his very best with the hair standing up upon his back. When he saw who it was, however, he jumped off and frisked round, licking my hand.

“That’s very strange,” I exclaimed.

“Not stranger than everything else,” said Bickley.

“What are you going to do?” I asked.

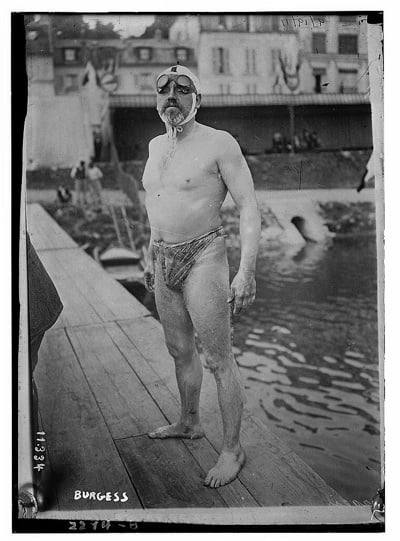

“Open these coffins,” he answered, “beginning with that of the old god, since I would rather experiment on him. I expect he will crumble into dust. But if by chance he doesn’t I’ll jam a little strychnine, mixed with some other drugs, of which you don’t know the names, into one of his veins and see if anything happens. If it doesn’t, it won’t hurt him, and if it does — well, who knows? Now give me a hand.”

We went to the left-hand coffin and by inserting the hook on the back of my knife, of which the real use is to pick stones out of horses’ hoofs, into one of the little air-holes I have described, managed to raise the heavy crystal lid sufficiently to enable us to force a piece of wood between it and the top. The rest was easy, for the hinges being of crystal had not corroded. In two minutes it was open.

From the chest came an overpowering spicy odour, and with it a veritable breath of warm air before which we recoiled a little. Bickley took a pocket thermometer which he had at hand and glanced at it. It marked a temperature of 82 degrees in the sepulchre. Having noted this, he thrust it into the coffin between the crystal wall and its occupant. Then we went out and waited a little while to give the odours time to dissipate, for they made the head reel.

After five minutes or so we returned and examined the thermometer. It had risen to 98 degrees, the natural temperature of the human body.

“What do you make of that if the man is dead?” he whispered.

I shook my head, and as we had agreed, set to helping him to lift the body from the coffin. It was a good weight, quite eleven stone I should say; moreover, it was not stiff, for the hip joints bent. We got it out and laid it on a blanket we had spread on the floor of the sepulchre. Whilst I was thus engaged I saw something that nearly caused me to loose my hold from astonishment. Beneath the head, the centre of the back and the feet were crystal boxes about eight inches square, or rather crystal blocks, for in them I could see no opening, and these boxes emitted a faint phosphorescent light. I touched one of them and found that it was quite warm.

“Great heavens!” I exclaimed, “here’s magic.”

“There’s no such thing,” answered Bickley in his usual formula. Then an explanation seemed to strike him and he added, “Not magic but radium or something of the sort. That’s how the temperature was kept up. In sufficient quantity it is practically indestructible, you see. My word! this old gentleman knew a thing or two.”

Again we waited a little while to see if the body begun to crumble on exposure to the air, I taking the opportunity to make a rough sketch of it in my pocket-book in anticipation of that event. But it did not; it remained quite sound.

“Here goes,” said Bickley. “If he should be alive, he will catch cold in his lungs after lying for ages in that baby incubator, as I suppose he has done. So it is now or never.”

Then bidding me hold the man’s right arm, he took the sterilized syringe which he had prepared, and thrusting the needle into a vein he selected just above the wrist, injected the contents.

“It would have been better over the heart,” he whispered, “but I thought I would try the arm first. I don’t like risking chills by uncovering him.”

I made no answer and again we waited and watched.

“Great heavens, he’s stirring!” I gasped presently.

Stirring he was, for his fingers began to move.

Bickley bent down and placed his ear to the heart —I forgot to say that he had tested this before with a stethoscope, but had been unable to detect any movement.

“I believe it is beginning to beat,” he said in an awed voice.

Then he applied the stethoscope, and added, “It is, it is!”

Next he took a filament of cotton wool and laid it on the man’s lips. Presently it moved; he was breathing, though very faintly. Bickley took more cotton wool and having poured something from his medicine-chest on to it, placed it over the mouth beneath the man’s nostrils —I believe it was sal volatile.

Nothing further happened for a little while, and to relieve the strain on my mind I stared absently into the empty coffin. Here I saw what had escaped our notice, two small plates of white metal and cut upon them what I took to be star maps. Beyond these and the glowing boxes which I have mentioned, there was nothing else in the coffin. I had no time to examine them, for at that moment the old man opened his mouth and began to breathe, evidently with some discomfort and effort, as his empty lungs filled themselves with air. Then his eyelids lifted, revealing a wonderful pair of dark glowing eyes beneath. Next he tried to sit up but would have fallen, had not Bickley supported him with his arm.

I do not think he saw Bickley, indeed he shut his eyes again as though the light hurt them, and went into a kind of faint. Then it was that Tommy, who all this while had been watching the proceedings with grave interest, came forward, wagging his tail, and licked the man’s face. At the touch of the dog’s red tongue, he opened his eyes for the second time. Now he saw — not us but Tommy, for after contemplating him for a few seconds, something like a smile appeared upon his fierce but noble face. More, he lifted his hand and laid it on the dog’s head, as though to pat it kindly. Half a minute or so later his awakening senses appreciated our presence. The incipient smile vanished and was replaced by a somewhat terrible frown.

Meanwhile Bickley had poured out some of the hot coffee laced with brandy into the cup that was screwed on the top of the thermos flask. Advancing to the man whom I supported, he put it to his lips. He tasted and made a wry face, but presently he began to sip, and ultimately swallowed it all. The effect of the stimulant was wonderful, for in a few minutes he came to life completely and was even able to sit up without support.

For quite a long while he gazed at us gravely, talking us in and everything connected with us. For instance, Bickley’s medicine-case which lay open showing the little vulcanite tubes, a few instruments and other outfit, engaged his particular attention, and I saw at once that he understood what it was. Thus his arm still smarted where the needle had been driven in and on the blanket lay the syringe. He looked at his arm, then looked at the syringe, and nodded. The paraffin hurricane lamps also seemed to interest and win his approval. We two men, as I thought, attracted him least of all; he just summed us up and our garments, more especially the garments, with a few shrewd glances, and then seemed to turn his thoughts to Tommy, who had seated himself quite contentedly at his side, evidently accepting him as a new addition to our party.

I confess that this behaviour on Tommy’s part reassured me not a little. I am a great believer in the instincts of animals, especially of dogs, and I felt certain that if this man had not been in all essentials human like ourselves, Tommy would not have tolerated him. In the same way the sleeper’s clear liking for Tommy, at whom he looked much oftener and with greater kindness than he did at us, suggested that there was goodness in him somewhere, since although a dog in its wonderful tolerance may love a bad person in whom it smells out hidden virtue, no really bad person ever loved a dog, or, I may add, a child or a flower.

As a matter of fact, the “old god,” as we had christened him while he was in his coffin, during all our association with him, cared infinitely more for Tommy than he did for any of us, a circumstance that ultimately was not without its influence upon our fortunes. But for this there was a reason as we learned afterwards, also he was not really so amiable as I hoped.

When we had looked at each other for a long while the sleeper began to arrange his beard, of which the length seemed to surprise him, especially as Tommy was seated on one end of it. Finding this out and apparently not wishing to disturb Tommy, he gave up the occupation, and after one or two attempts, for his tongue and lips still seemed to be stiff, addressed us in some sonorous and musical language, unlike any that we had ever heard. We shook our heads. Then by an afterthought I said “Good day” to him in the language of the Orofenans. He puzzled over the word as though it were more or less familiar to him, and when I repeated it, gave it back to me with a difference indeed, but in a way which convinced us that he quite understood what I meant. The conversation went no further at the moment because just then some memory seemed to strike him.

He was sitting with his back against the coffin of the Glittering Lady, whom therefore he had not seen. Now he began to turn round, and being too weak to do so, motioned me to help him. I obeyed, while Bickley, guessing his purpose, held up one of the hurricane lamps that he might see better. With a kind of fierce eagerness he surveyed her who lay within the coffin, and after he had done so, uttered a sigh as of intense relief.

Next he pointed to the metal cup out of which he had drunk. Bickley filled it again from the thermos flask, which I observed excited his keen interest, for, having touched the flask with his hand and found that it was cool, he appeared to marvel that the fluid coming from it should be hot and steaming. Presently he smiled as though he had got the clue to the mystery, and swallowed his second drink of coffee and spirit. This done, he motioned to us to lift the lid of the lady’s coffin, pointing out a certain catch in the bolts which at first we could not master, for it will be remembered that on this coffin these were shot.

In the end, by pursuing the same methods that we had used in the instance of his own, we raised the coffin lid and once more were driven to retreat from the sepulchre for a while by the overpowering odour like to that of a whole greenhouse full of tuberoses, that flowed out of it, inducing a kind of stupefaction from which even Tommy fled.

When we returned it was to find the man kneeling by the side of the coffin, for as yet he could not stand, with his glowing eyes fixed upon the face of her who slept therein and waving his long arms above her.

“Hypnotic business! Wonder if it will work,” whispered Bickley. Then he lifted the syringe and looked inquiringly at the man, who shook his head, and went on with his mesmeric passes.

NEXT WEEK: “For a while she looked at me with an earnest, searching gaze, then suddenly, for the first time moving her arms, lifted them and threw them round my neck. The old man stared, bending his imperial brows into a little frown, but did nothing. Bickley stared also through his glasses and sniffed as though in disapproval, while I remained quite still, fighting with a wild impulse to kiss her on the lips as one would an awakening and beloved child.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.