B IS FOR BANANA KETCHUP

By:

February 18, 2023

An installment in CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM, an apophenic food-history series from HILOBROW friend Tom Nealon, author of the seminal book Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (2016 UK; 2017 US); and also — here at HILOBROW — the popular series STUFFED (2014–2020) and DE CONDIMENTIS (2010–2012).

CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM: SERIES INTRODUCTION | AIOLI / ANCHOVIES | BANANA KETCHUP / BALSAMIC VINEGAR | CHIMICHURRI / CAMELINE SAUCE | DELAL / DIP | ENCURTIDO / EXTRACT OF MEAT | FURIKAKE / FINA’DENNE’ | GREEN CHILE / GARUM | HOT HONEY / HORSERADISH | INAMONA / ICE | JALAPEÑO / JIMMIES | KECAP MANIS / KIMCHI | LJUTENICA / LEMON | MONKEY GLAND SAUCE / MURRI | NƯỚC CHẤM / NUTELLA | OLIVE OIL / OXYGALA | PIKLIZ / PYLSUSINNEP SAUCE | QIZHA / QUESO | RED-EYE GRAVY / RANCH DRESSING | SAMBAL / SAUERKRAUT | TZATZIKI / TARTAR SAUCE | UMEBOSHI / UNAGI SAUCE | VEGEMITE / VERJUS | WHITE GRAVY / WOW-WOW SAUCE | XO SAUCE / XNIPEK | YOGHURT / YEMA | ZHOUG / ZA’ATAR | GOOD-BYE TO ALL TZAT(ZIKI).

María Orasa famously invented mass-produced banana ketchup during the Filipino tomato shortage caused by World War II. (She also invented the nutritional supplements Soyalac and Darak and, as a member of the Filipino resistance army Marking’s Guerillas, smuggled them into Japanese concentration camps; first-class food-chemistry badass). To this day, banana ketchup remains an under-appreciated and impressive invention.

If you’ve never tasted banana ketchup it tastes like… ketchup. It remains immensely popular in the Philippines and spots in the Caribbean. Orasa understood something very fundamental about ketchup that has been lost: It is a condiment of convenience, a way to use something that there’s too much of, a way to turn a surfeit into a product. The history of ketchup is a history of foods we had too much of. These days it’s tomato, but in the 19th century we had:

- Walnut ketchup

- Cockle ketchup

- Oyster ketchup

- Mushroom ketchup

- Cucumber ketchup

- White ketchup (anchovy ketchup)

- Pistachio ketchup

- Cranberry ketchup

- Pepper ketchup

- Damson ketchup

- Gooseberry ketchup

- Elderberry ketchup

- Grape ketchup

- Herring ketchup

- Apple ketchup

- Apricot ketchup

- Peach ketchup

- Squash ketchup

- Whortleberry ketchup

And many more. Every one of these — even the fruit ketchups and sea-creature ketchups — would have, I have come to believe, tasted sort of the same. Maybe not as similar as tomato ketchup and banana ketchup, but serving the same basic purpose.

We tend to get stuck on the tomato part of ketchup, as if that is what defines it… but it’s really the opposite, the everything but tomato which makes ketchup. Vinegar (maybe lemon), salt, and maybe (though not always) a few savory spices like garlic, black pepper, and then a group of “sweet” spices, usually from among ginger, mace, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, allspice. There is remarkably little variation even when the named ingredients seem most wildly disparate.

For example, peach ketchup is composed of peaches, ginger, cloves, vinegar, mace, lemon, allspice, sugar, pepper, cinnamon. Oyster ketchup is composed of oysters, mace, cloves, allspice, cayenne, salt, white wine.

Our knowledge of ketchup is inside-out and backwards; its defining characteristic, as we supposed, was merely an obfuscation. The names — tomato, anchovy, whortleberry, walnut — were only masks. Underneath, there is just the one ketchup.

Balsamic vinegar is made in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy with their local not-very-good-for-wine lambrusco and trebbiano grapes. In fact, mosto, a cooked-down juice made from these grapes, is already a condiment; balsamic vinegar is a second-order condiment.

Traditionally, the mosto is cooked down, then acted on by acetic-acid bacteria. It’s put in a barrel and stored in an attic for years and years until it became mellow and thick. As it evaporates, and the flavors develop (because of the heat of the Italian summers, the juice goes through something similar to the Maillard reaction — which imparts the “browned” flavor to roasted foods), it is then transferred to different barrels. Sometimes dozens of barrels over dozens of years. It’s a classically pre-capitalist, intensely regional product.

So, of course, we’ve spread it all over the world. And the version we tend to encounter (as I complained in a 2011 HILOBROW post) isn’t even a debased version of traditionally prepared balsamic vinegar; it’s a completely fraudulent one.

What interests me about balsamic, these days, however, is how even these utterly fraudulent balsamic vinegars are… still pretty good. Good enough that I think it may be worth adulterating them urther, not only so that they will cost even less — but also in order to move them out of the uncanny valley by transforming them into fully, honestly, and complete above-board fakes.

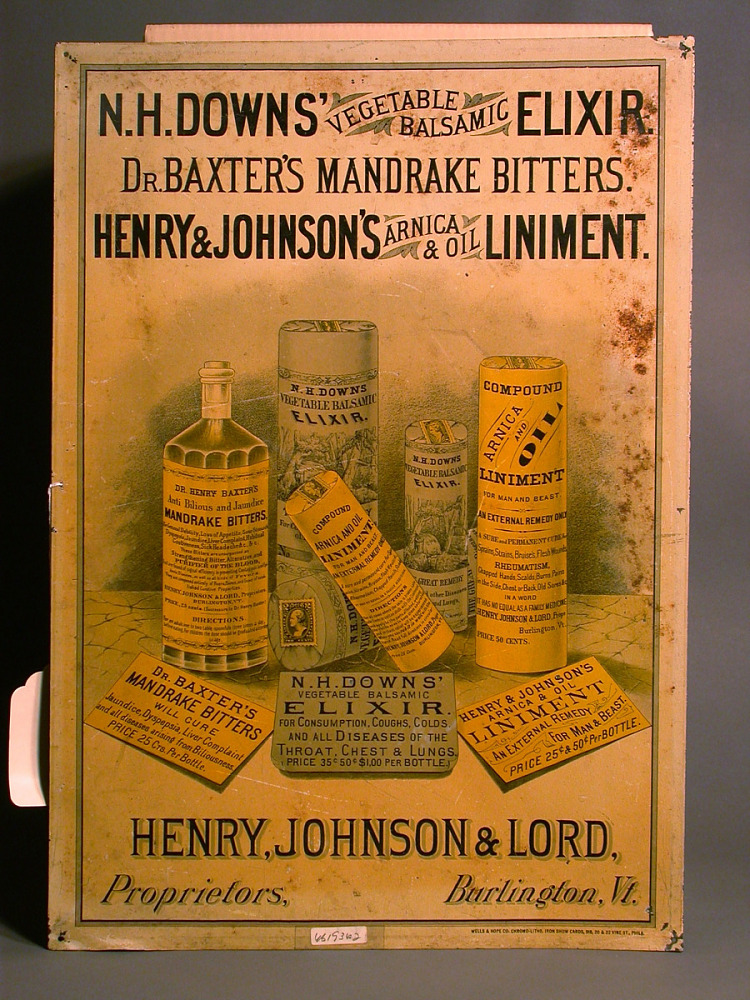

As a side note, these vinegars are called balsamic because of their supposed salubrious properties, just like a popular group of quack medicines in the middle of the 19th century. Usually called “balsamic elixir” and going by a number of trade names (Congreve’s, Downs’), the elixir was marketed as “A Specific for Every Species of Cough, Hooping-cough, and Asthma, and the Incipient Stages of Consumption.” Sometimes they would subtract or add one or two indications (bronchitis, for example). “People die of consumption simply because of neglect, when the timely use of this remedy would have cured them at once,” according to one 1882 advertisement. “Put aside your opium and use Congreve’s” was a common pitch — because Downs’ Elixir had a touch of opium in it).

The point is, balsamic as a concept has a rich history of prevarication, obfuscation and adulteration — a history to which I would like to add the following recipes of my own:

Balshamic Vinegar

- Take 4 parts white vinegar; 1 part blackstrap molasses; pinch of salt. Heat gently, sugaring to taste.

- Dissolve 1 heaping tablespoon of sugar in a small amount of water. Heat until it just starts to brown. Add white vinegar to taste

Or, reduced to its fraudulent pith, try this:

For both recipes: If making a “balshamic” vinaigrette, simply add a teaspoon of xanthan gum, oil, and shake vigorously.

TOM NEALON at HILOBROW: CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM series | STUFFED series | DE CONDIMENTIS series | SALSA MAHONESA AND THE SEVEN YEARS WAR | & much more. You can find Tom’s book Food Fights & Culture Wars here.