J IS FOR JALAPEÑO

By:

May 21, 2023

An installment in CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM, an apophenic food-history series from HILOBROW friend Tom Nealon, author of the seminal book Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (2016 UK; 2017 US); and also — here at HILOBROW — the popular series STUFFED (2014–2020) and DE CONDIMENTIS (2010–2012).

CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM: SERIES INTRODUCTION | AIOLI / ANCHOVIES | BANANA KETCHUP / BALSAMIC VINEGAR | CHIMICHURRI / CAMELINE SAUCE | DELAL / DIP | ENCURTIDO / EXTRACT OF MEAT | FURIKAKE / FINA’DENNE’ | GREEN CHILE / GARUM | HOT HONEY / HORSERADISH | INAMONA / ICE | JALAPEÑO / JIMMIES | KECAP MANIS / KIMCHI | LJUTENICA / LEMON | MONKEY GLAND SAUCE / MURRI | NƯỚC CHẤM / NUTELLA | OLIVE OIL / OXYGALA | PIKLIZ / PYLSUSINNEP SAUCE | QIZHA / QUESO | RED-EYE GRAVY / RANCH DRESSING | SAMBAL / SAUERKRAUT | TZATZIKI / TARTAR SAUCE | UMEBOSHI / UNAGI SAUCE | VEGEMITE / VERJUS | WHITE GRAVY / WOW-WOW SAUCE | XO SAUCE / XNIPEK | YOGHURT / YEMA | ZHOUG / ZA’ATAR | GOOD-BYE TO ALL TZAT(ZIKI).

When I was a young we used to go to this Mexican place. It was of a type that was popular in the 1970s but is hard to find now: white tablecloths, formal dress for the waiters, a mariachi vihuelist wandering from table to table on weekends. It was a whole thing. For some reason my silly suburban town had the second branch of a popular Greenwich Village restaurant called Pancho Villa’s,so, whatever (probably a little dopey) take on Mexican was happening in New York at the time, their food was a really good version of it. They had a few Tex-Mex things, hard tacos, chimichangas, but it was mostly enchiladas: cheese, chicken, beef (ground), Suizas, even a mole or two.

They served these amazing individually prepared nachos — a perfect triangular tortilla chip with a layer of refrito, a thick layer of cheese (probably asadero), and a single perfect pickled jalapeño slice on top like a tiny crown. When I was a kid these were the nachos we would try to replicate at home — this chip dressed up as a canape — and to this day, my Platonic ideal of a nacho is this Pancho Villa version, even though I have never seen anyone else do them like this since. But you should — you can get the balance of flavors just right this way, and it prevents you from eating coal-shovel style which, as I get older, can’t hurt.

As a result, even though jalapeños are the most overexposed of chile peppers (though we are getting there with their smoked alter-ego, the chipotle), they still seem a little magic. Of course, they are also, in their sliced, pickled form, a really good, versatile condiment. Great on a sandwich, in a rice dish, and especially good perched on top of a single bespoke nacho.

In Boston and Philadelphia they call sprinkles — those little rods or spheres of candy that you put on ice cream — jimmies. No one ever knew why, and at some point in the last few decades people decided that it was probably racist (a fair assumption, considering) and derived (maybe) from Jim Crow and the (apocryphal) fact that it was the

chocolate sprinkles that were referred to this way (it was all sprinkles, chocolate and rainbow). But where did they come from and why call them jimmies?

The chocolate ones popped up first and seem to be a 19th century Dutch invention — they, naturally, put them on bread for breakfast which is what you do with chocolate when you are Dutch. They became popular in the U.S. early in the 20th century (as candy-making manufacturing innovated) and started to be called Jimmies by the late 1920s. A Brooklyn candy company called Just Born has tried to take credit, as has Boston’s The Jimmy Fund, though both are too late to be the source. My favorite is the story of a mother who chopped up candies to put on sundaes for her son Jimmy’s birthday. When other kids shouted “Hey, can I have some of those” (pointing at the sprinkles on his sundae), she said “those are Jimmy’s!”

I propose a new source for the name: In the early 20th century Boston and Philly were both rail and ice-cream hubs. Most of the important early American ice ream originated in one or the other: In Boston, Frederick Tudor, ice mogul turned ice-cream salesmen in the first half of the 19th century, then Schrafft’s and Bailey’s in the second half and Brigham’s in the early 20th. In Philly, they basically invented American style ice-cream — in most 19th century cookbooks there are two types of ice-cream listed, Neapolitan and Philadelphia style.

James Hemings, the enslaved brother of Sally Hemings, was taken to France by Thomas Jefferson and sent to cooking school — he was the first American documented to have been trained as a chef in France — and brought back the secrets of ice cream (as well as macaroni-and-cheese and others). In the 1830s, another African American chef, Augustus Jackson (born in Philly in 1808), who worked at the White House in the 1820s, brought ice cream to Philadelphia. There he developed methods for ice-cream manufacturing and one of the first freezers; this led to the birth of the Philadelphia style and the Philadelphia ice-cream businesses — beginning with Breyers and Bassets in the mid 19th century.

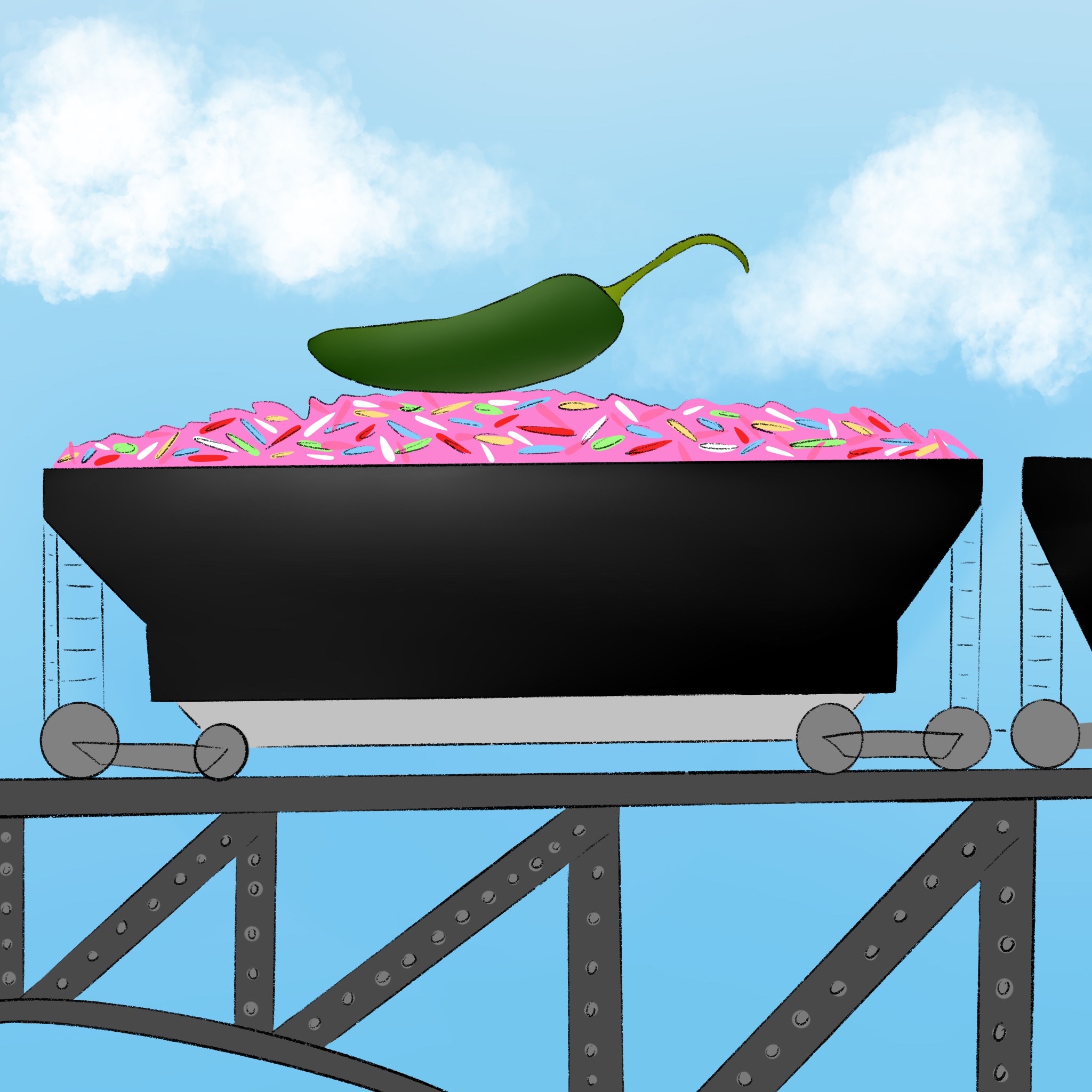

In both cities they started serving these new candies on top of ice-cream at shops and pharmacies. The sprinkles were kept in long rectangular bins for easy dispensing — the bins resembled railcar coalhoppers with the sprinkles instead of coal or gravel heaped up in a mound on top. In the 19th and early 20th century these cars (now called hoppers or gondolas depending on whether they have fixed bottoms) were called jimmies. Because they seized on the name “jimmies” in Boston and Philly just as it, in train parlance, was going out of fashion, it never had the same resonance when sprinkles caught on in the rest of the country. And, as the Just Born story of jimmies origins shows, they did call them jimmies in NYC, at least for awhile, but then they stopped and switched to sprinkles. Language is funny.

Unlike most of the condiments I’ve talked about here, I can’t really recommend jimmies — I’ve always just found them to be an irritating impediment to eating ice cream. But at least they aren’t racist.

TOM NEALON at HILOBROW: CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM series | STUFFED series | DE CONDIMENTIS series | SALSA MAHONESA AND THE SEVEN YEARS WAR | & much more. You can find Tom’s book Food Fights & Culture Wars here.