With the Night Mail (Intro)

By:

February 5, 2018

In 2012, HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Rudyard Kipling’s 1905 Radium Age sci-fi novella With the Night Mail (and the 1912 sequel “As Easy As A.B.C.”) in paperback form. Matthew De Abaitua, author of the science fiction novel The Red Men (and since then: IF THEN and The Destructives), provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

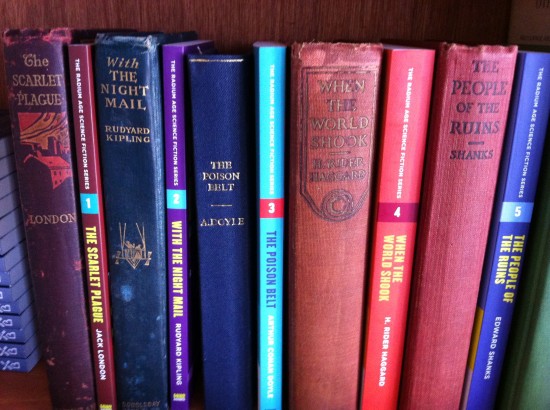

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

In 1870, the Prussian army laid siege to Paris, a city of Jules Verne modernity. This Paris harboured malfunctioning prototypes of the future — the mitrailleuse machine gun and Le Plongeur submarine — and aborted deranged technologies such as Jules Allix’s long-distance communication system based on the telegraphic escargot fluid of “sympathetic snails,” a fever dream of quantum entanglement. Hemmed in by the Prussian military, Parisians were forced to dine on rats or — if they were lucky — choice cuts from the exotic species in the city zoo.

The only way out of the siege was up. In the disused termini of the imprisoned city — the Gare Du Nord and Garde d’Orléans — lines of seamstresses manufactured hot air balloons to be launched from the Solferino Tower in Montmartre bearing military orders and American arms dealers. Stinking with gas and reliant upon a favourable weather forecast, the balloons flew in jagged haphazard fashion over enemy lines. Their flight was observed by two Prussian officers whose names would soon float above the world: Lieutenant Paul von Hindenburg and Captain Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Four years later, the German Postmaster General Heinrich von Stephan gave a lecture on “World Mail and Air Travel.” The post- master reminded his audience of the Prussian siege of Paris and how over sixty balloons had escaped carrying mail. After reading an account of this lecture, Count Zeppelin turned to his diary and, under the heading “Thoughts About an Airship,” set down his vision of the dirigible: it must have the dimensions of a big ship, be dynamically powered, and constructed of longitudinal girders and rings each of which would contain an individual gas cell or gasbag.

In a dirigible — from the French diriger (to steer) — the aeronaut steers through the wind. The technology for a steerable balloon had been invented at the same time as the first balloon flight of the Montgolfière in 1783: gasbags or internal envelopes within the balloon in which air pressure could be increased or decreased without venting hydrogen, thereby controlling buoyancy and altitude over a prolonged duration. Additional propulsion was required, and could be provided by a screw or propellor as in a steam ship. But a steam engine was too heavy for air travel, and so the dirigible had to wait a hundred years for the invention of the lighter petrol combustion engine.

After retiring from the military at 52, Count Zeppelin turned his dream of an airship into a reality and flew the LZ-1 on July 2 in 1900, powered by two Daimler petrol engines. The flight lasted eighteen minutes.

Advocates of the aeroplane argued with the believers in the balloon as to which method would prove to be the future of air travel. This argument is dramatised in Jules Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds (1886) in which a balloon society is scandalised by the aeronaut Robur; he dismisses the dirigible and unveils his aeroplane, a “clipper” a hundred feet long and twelve feet wide with thirty seven masts each bearing two propellors, and powered by electricity: the faux science of the ship — that is, the dilithium crystals in its warp engines — are the acids and construction of accumulators that generated such currents, and all unpatented. The endurance of the airship as symbol of alternative history, a steampunk cliche, derives from the arguments dramatised in Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds: aeroplanes or dirigibles, two time streams, two possible futures.

Flight was a symbol of fin de siècle futurity, a standard entry in predictions of what the twentieth century would hold. Verne’s con- temporary Albert Robida explores these prophecies in his novel Vingtième Siècle (1882) and in his illustrations of a future Paris. Robida painted airborne socialites docking on platforms to dine in restaurants in the sky and cavalry riding batwing rockets into battle. With the turn of the century, the playfulness of the balloon was challenged by the dirigible. If the Montgolfière represented the wandering aimless flight of whimsy, the Zeppelin fused imagination to the will to become an object feared and adored: the technological sublime.

In the First World War, the Zeppelin was deployed in the bombing of London. In a letter of 1915, D.H. Lawrence observes the bright golden finger of the airship as it destroys the old order and points the way toward what will replace it: “Then we saw the Zeppelin above us, just ahead, amid a gleaming of clouds: high up, like a bright golden finger, quite small, among a fragile incandescence of clouds. And underneath it were splashes of fire as the shells fired from the earth burst. Then there were flashes near the ground — and the shaking noise. It was like Milton — then there was war in heaven. But it was not angels. It was that small golden Zeppelin, like a long oval world, high up. It seemed as if the cosmic order were gone, as if there had come a new order, a new heaven above us: and as if the world in anger were trying to revoke it. Then the small, long-ovate luminary, the new world in the heavens, disappeared again… So it is the end — our world is gone.”

The airship was an ideal of the new order and the means of achieving it. In H.G. Wells’ War In The Air (1908), a German air fleet bombs New York. The war fleet consists of the “lineal descendants of the Zeppelin airship that flew over Lake Constance in 1906”; that is, the LZ2, which more closely resembled an intercontinental missile than the bosomy bloat of later craft. War In The Air depicts a dozen German airships destroying the American naval fleet from a height of two thousand feet before arriving in New York in late afternoon. The airships loom over the city in the same way that the enormous UFOs of V, Independence Day and District 9 are suspended impossibly above the heads of the citizens. The apocalypse is preceded by weightless moments of delicious anticipation: “there the monsters hung, large and wonderful in the evening light, serenely regardless of the occasional rocket explosions and flashing shell-bursts in the lower air.”

New York surrenders to the airships and then rebels: “In this manner the massacre of New York began,” writes Wells. “She was the first of the great cities of the Scientific Age to suffer by the enormous powers and grotesque limitations of aerial warfare… it was impossible to subdue the city except by largely destroying it.” Nation states unleash fleets of airships. World War begins. European civilisation is blown up and “within five years it was altogether disintegrated and destroyed.” Written seven years prior to the beginning of the First World War, Wells’ closing lines anticipate the way in which war can overtake a civilisation: “somebody somewhere ought to have stopped something.”

Wells got his eschatological kicks in envisioning the collapse of nation states and their replacement by a new world order: “it is chaos or the United States of the World for mankind,” he wrote. After the First World War, in an article for the Atlantic Monthly, he pressed his belief in a League of Nations: the technological contrivances of science would make war borderless and increasingly destructive and so a unification of world states, following the progressive direction of history, would prevent the apocalyptic conflicts of the future. The League of Nations failed largely because the United States ignored it. An alternative timeline can be discerned: in the midst of the First World War, Zeppelin commander Peter Strasser had sought permission to bomb New York to arrest the flow of supplies to the allies. Had Strasser’s plan gone ahead, would it have been a Pearl Harbor moment to lead America into the League of Nations?

The two stories by Rudyard Kipling collected in this volume, With the Night Mail: A Story of 2000 AD Together with Extracts from the Magazine in Which It Appeared, first published in McClure’s Magazine in 1905 and reprinted in volume form in Actions and Reactions (1909), and its sequel “As Easy as A.B.C.,” first published in 1912 in London magazine, and collected in A Diversity of Creatures in 1917, depict the role of airships in a new world order and are founding works of science fiction, or scientific romance as it was then called.

With the Night Mail is a journalistic account of a run aboard an airship carrying the mail from London to Quebec. From his late teenage years to his mid-twenties, Kipling worked on newspapers in Lahore and Allahabad, and he uses newsprint conventions for verisimilitude: the report of the story is followed by various advertisements, notes and correspondence from the future world of 2000 AD.

In the story itself, Kipling uses spurious technical terms to cultivate the reader’s credulity: terms such as Fleury’s Ray and colloid — which appears to be a kind of cellulose transparent substance used instead of glass for the portholes of the airship. Contemporary anxieties concerning German manufacturing appear when an airship using “German compos in their thrust-blocks” suffers difficulties. British manufacturing is “a shining reproof to all low-grade German ‘ruby’ enamels, so-called ‘boort’ facings, and the dangerous and unsatisfactory alumina compounds which please dividend-hunting owners and turn skippers crazy.”

Arnold Bennett described With the Night Mail as “a glittering essay in the sham technical.” He complained that mechanics displaced psychological accuracy, a perennial literary criticism of science fiction (C.S. Lewis observed that Arthur C. Clarke’s stories were “engineer stories”). Kipling, with his obsession for motor cars and anti-intellectualism, delighted in the mechanical. Unlike other writers with literary reputations who have utilised science fiction tropes, Kipling is more interested in the nuts and bolts of the future than any grand ideas. He utilises a wide practical vocabulary with nautical terms such as caisson — a watertight chamber — overlapping with technological neologisms, a stylistic tactic similar to that presented by Ridley Scott in Alien: a weathered blue-collar future in which people still had to go to work.

The night mail airship slips its mooring tower and lights out across Ireland, passing over Valentia Island, landing point of the early transatlantic telegraph wires that connected Britain to the New World. Navigation through the cloudscape is made possible by cloud breakers, powerful lights beamed up from the earth and coloured according to region (green for Ireland, inevitably). Kipling imagines the scene vividly: “He points to the pillars of light where the cloud-breakers bore through the cloud-floor. We see nothing of England’s outlines: only a white pavement pierced in all directions by these manholes of variously coloured fire.” A master of action, Kipling’s scenes of airship destruction are exhilarating; a stricken airship is driven from the shipping lanes by dropping a sofa-sized pithing-iron through its hull: “The derelict’s forehead is punched in, starred across, and rent diagonally. She falls stern first, our beam upon her; slides like a lost soul down that pitiless ladder of light, and the Atlantic takes her.”

The height of the adventure is the navigation of a fierce storm. The pilot, in an inflatable suit, flies the airship by hand through a landscape of crackling electricity, St. Elmo’s fire and charged Krypton vapours. Kipling’s mystical meteorology is an alluring example of how in the early years of the century advances in scientific knowledge had not completed their separation from supernatural and religious modes of thought. For a Victorian gentlemen adjusting to Edwardian future shock, the telephone was on the same timeline as the spiritualist’s knock on the table. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote of the rational observation of Sherlock Holmes while believing in fairies at the bottom of the garden. The Society of Psychical Research pursued poltergeists with the rigour of amateur archaeologists. The overlap between induction, Marconi, and spiritualism forms the basis of Kipling’s short story “Wireless,” in which a consumptive picks up on the signal of the poet John Keats, presumably across the ether so beloved of Victorian physicists. The categories are in the process of being defined. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit priest whose mystical-scientific conception of the noösphere would go onto inspire the post-human movement, was thrilled by the play of the supernatural and the mechanical within Kipling’s stories; “they make ships and locomotives speak, they make you feel with the eastern soul.”

The back story of With the Night Mail concerns the semi-elected, semi-nominated body of a few score of persons of both sexes who control the planet: the Aeronautical Board of Control, or A.B.C., a technocracy with the motto of “Transport is Civilisation.” “As Easy as A.B.C.,” the sequel to With the Night Mail, is set sixty-five years later and explores the global governance of this supranational agency. The prospect of a World Government is as much a futuristic trope of the era as the airship, and was a political cause advanced by H.G. Wells’ United States of the World and the League of Peace advocated by Theodore Roosevelt’s Nobel acceptance speech in 1910. Roosevelt and Kipling were friends and the A.B.C. and the League of Peace stem from their hearty can-do masculinity. The rule of law is dictated by “the wise and strong,” pugnacious types who despise cowards and bullies alike. In the words of Roosevelt, “No nation deserves to exist if it permits itself to lose the stern and virile virtues.” The association of the tumescent dirigible with virile order is undeniable; to paraphrase Freud, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar but an airship is never merely an airship.

The future of the A.B.C. is neither degenerate nor especially virile. Technological advance has transformed the dirigibles of the Night Mail into craft that shoot up rocket-fashion “like the ‘aeroplane’ of our ancestors.” In 2065, democracy is a disease belonging to a by-gone age of crowds. There has been no media or news sheets for twenty-seven years as they infringe upon privacy, and privacy is the paramount virtue of the future. Mankind has spread apart on the face of the earth, its numbers controlled and falling. Crowds and the “people” are bogeymen. War is obsolete. The A.B.C. maintains a fleet to deal with outbursts of democratic sentiments, and one such mission forms the basis of the story.

Kipling’s ambiguity toward this future is apparent: authority figures weep at the deployment of non-lethal light and sound weapons, so unaccustomed have they become to death. With everyone provisioned and cared for by a benign technocracy, the peaks and troughs of life’s oscillation are trimmed. It is an era averse to risk and waning nations gladly give up self-determination to the A.B.C. This passive compliance with the supranational technocracy, long portrayed as evidence of Kipling’s misanthropy, is prophetic of the current response of an exhausted debt-burdened Europe to financial crisis.

During the writing of these two stories, Kipling lived in the remote estate of Bateman’s in East Sussex. The highpoint of Kiplingism was the 1890s when it was a vital force in the school days of H.G. Wells. By 1910, Kipling’s reputation was eclipsed by the onset of modernism in Britain with Roger Fry’s exhibition of Post-Impressionism. It was the year when everything changed, according to Virginia Woolf. As Edmund Wilson observes, Kipling was only forty-five at this time, yet he was “dropped out of modern literature” and became “the thick, dark and surly little man who had dug himself into Bateman’s, Burwash, Sussex.” It is appropriate that his future of 2065 is a depopulated world obsessed with privacy, the three million citizens of London dispersed easily across outlying towns — the current population of London is more than twice that and is packed into a much smaller area.

The airships of the A.B.C enforce elite rule from a dispassionate vantage point in the clouds. Democracy came from the ground up, the mass enfranchisement of the man of the street. Kipling’s stories are an anxious response to the advancing power of the crowd and indicative of his personal isolation.

The benign anti-democratic rule of Kipling’s A.B.C. anticipate the direction of H.G. Wells and his followers in the 1930s. The journal of the H.G. Wells society, Cosmopolis, advanced the cause of world unity then merged with The Plan, the journal for the Federation of Progressive Societies and Individuals. The disparate groups of the left recognised the need to band together to resist the fascist agglomeration, an aggressive praxis that Wells described in a lecture as “liberal fascism.” They stood for a planned economy, the rule of the intellectual, production for use rather than profit and resistance to the racial myths and discredited eugenics of Hitler. One clear distinction between liberal fascism and its Nazi enemy was that the airships of the progressive forces remained on the drawing board of the imagination.

1937. Mid-afternoon in Manhattan. The Luftschiff Zeppelin #129 drifts over the south side of the island, its long shadow passing over the nail bed of the New York skyline. With a swastika on its tail fins, the Hindenburg is the Nazi herald and possesses the weightless solidity of a dictator.

Four and half hours later, as the airship manoeuvres toward a mooring mast in a field in Lakehurst, New Jersey, a mushroom-shaped flower of flame bursts in front of its upper fin. The roaring advance of the fire peels back the outer skin of the bow to reveal the bulkhead, and for an instant, the exposed skeleton is intact. The gaseous interior of the airship blazes. The structure melts and collapses face first into the earth. On the ground, sailors run toward the burnt bones.

The blazing Hindenburg cauterises the timeline of the airship. One future is destroyed and another takes its place. The dirigible becomes a symbol of the hallucination of security of day-to-day life, a hallucination that may one day crumple to earth — in the words of H.G. Wells — “like an exploded bladder.”

MARCH — JUNE 2012

Rudyard Kipling was an English poet, prophet of British imperialism, and author of such immortal novels and stories as The Jungle Book, Kim, Just So Stories, and “The Man Who Would Be King.” He also wrote Radium Age science fiction.

“It is a glittering essay in the sham-technical; and real imagination, together with a tremendous play of fancy, is shown in the invention of illustrative detail.” — Arnold Bennett (1917)

“A most remarkable little story… It is rather a fascist picture which Kipling gives us.” — Norbert Weiner, The Human Use of Human Beings (1950)

“An amazing tour-de-force of inspired genius — Kipling, in 1905, is doing things that science fiction as a genre wouldn’t achieve until Robert Heinlein arrived in the late 1940s.” — Bruce Sterling (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.