Screen Time (10)

By:

December 13, 2015

One in a series of 10 posts reprinting Jacob Mikanowski’s film and television writing from Bright Lights Film Journal and elsewhere.

This essay first appeared in Bright Lights Film Journal.

Cowboy Bebop (1997–98), dir. Shinichirō Watanabe.

For the six weeks it was on, it was the most beautiful thing on television. It was worth staying up to 1:30 in the morning just to see the credits: silhouettes moving to music, a jazz riff on the Ennio Morricone-scored opening to A Fistful of Dollars. The rest of the show looked just as good. Japanese animators could nail the look of just about anything: ice cubes swirling in a tumbler of whiskey, vegetables jumping in a wok, a saxophone under club lights, an open refrigerator spinning in zero gravity. Nothing about it was forced, no matter the plot — and since the crew of the Bebop are all bounty hunters, no matter the bounty. The show always made space for killing time. Every night the crew cooked, played dice, watched TV, lazed around.

The tall one, Jet, in the overalls with the robotic arm and Regency whiskers, is a Charlie Parker fan. Spike, in the blue suit, yellow shirt and pencil tie, looks a little like Bob Dylan ca. Blonde on Blonde, but prefers Bruce Lee. Faye Valentine (that’s not her real name) wears a gold halter top and carries a serious-looking semiautomatic, though we suspect she’s a softie underneath. Ed is twelve and might be a boy or a girl; he/she splits duties as house pet with a Welsh corgi.

It could afford to kill time because when it was in storytelling mode, Cowboy Bebop had the tightest rhythm in TV: four seconds an image, an hour’s worth of narrative in ten frames. But the real pleasure was always in hanging out: watching Spike down a hangover cure, Jet prune his bonsai, Faye sunbathe, Ed noodle on his/her computer.

The family is the basic unit of popular drama — the family threatened, the family torn asunder, the family put back together. The four bounty hunters of the Bebop are a sort of family, but that isn’t their story.

Dave Hickey wrote that the great thing about Perry Mason was that it reconstituted “the ideal of the American family in its original 19th century from, as a quasi-democratic mercantile unit (the family farm, the family firm, the vaudeville act) as a collective endeavor in which the static rigor of single-provider patriarchy is mitigated by issues of competence and merit, by the exigencies of collaboration, and, finally, by the ethics of the task at hand.” That is, it shifts the central plot of popular drama from the family in peril to the family as a group of people committed to getting something done and getting it done right.

That’s closer to what Cowboy Bebop is about, but it isn’t all of it.

For Americans my age, in their late teens and early twenties, the important relationships aren’t business or family but roommates. For a decade or so, you live with groups of people, brought together more or less randomly. Roommates aren’t family, and they’re not business partners. They share no collective endeavor but making rent.

Cowboy Bebop is a roommate show. People live together, bitch about being broke, eat the last thing in the fridge, use up all the hot water. It indulges the great roommate fantasy. Because, at the end of twenty-six episodes these four stand-offish strangers temporarily sharing close quarters but coming and going as they please know each others’ pasts and watch each others’ backs. And that’s what you hope for from roommates: that eventually they’ll get you, they’ll understand you, without having to say a word, four seconds at a time.

Batman: The Animated Series (1992–95).

Four years ago my district attorney, Ray Gricar of State College, Pennsylvania drove his red Mini Cooper over the mountains and walked into the woods, never to be heard from again. Word was he was having an affair in the office. A short while later fishermen found his laptop in the Susquehanna, but the hard drive had been pulled out.

Reading about all this I thought back to the Batman cartoon I used to watch on Pennsylvania mornings. It stood out in that kid-friendly lineup like a goth girl at the prom. You could tell because of all the shadows, even in the dark. Who was bothering to spotlight Gotham with twilight shadows even after the sun went down?

It took me fifteen years to realize just how dark those alleyways were. I was teaching Freud when the Elliot Spitzer scandal broke. And all of a sudden I understood the meaning of Batman.

It takes a little explaining; it helps to be acquainted with Henry Edelheit’s article on crucifixion fantasies and the primal scene (International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 1974). But in brief, it goes something like this: the origin of Bruce Wayne’s crime-fighting compulsion is supposed to reside in the trauma of seeing his parents murdered. This trauma becomes linked to his phobia of bats — present both at his parents’ death and underneath the family mansion — and its overcoming becomes tied to his obsessive quest for justice. Hence the psychic equation runs coward/bat-phobe into avenger/bat.

But were Bruce’s parents really murdered in that alleyway? Where exactly was the dank, dim, furry (so many bats!) cave in which his father embraced his mother for the last time while she cried out in pain, over and over again?

It doesn’t take a long course in Kleinian therapy to realize that young Bruce had caught his parents in the act of intercourse, and that he dedicated the rest of his life to restaging it in hopes of exorcise himself of hold it had on his mind. Primal scene trauma normally leads to sexual perversity, exhibitionism and voyeurism — pretty much what you’d expect for a detective wearing a latex cowl with pointy ears driving a rocket-propelled phallus. Even so, a case of a man making it his life’s work to spy on others while wearing a suit — which by the symbolic logic of the primal scene represents both the terrifying union of his parents and his mother’s pubic hair — must be unique to psychoanalysis. And what are we to make of his surrogate family, Batgirl and Robin, forced to don the same troubled pelt?

But of course all true detectives are just variations on Freud (don’t believe me — watch House and tell me why lies are to blame for every week’s illness instead of microbes). Which maybe goes some of the way to explaining the problem with district attorneys: how else to account for Spitzer’s compulsion, Giuliani’s fascism and Ray Gricar’s disappearance? Being a citizen may take nothing more than a willingness to trust your own judgment as much as you do that of your fellows. But to devote yourself to public service, to throw oneself into fighting corruption and crime, does that take dedication and public-spiritedness, or obsession, perversion, and exhibitionism?

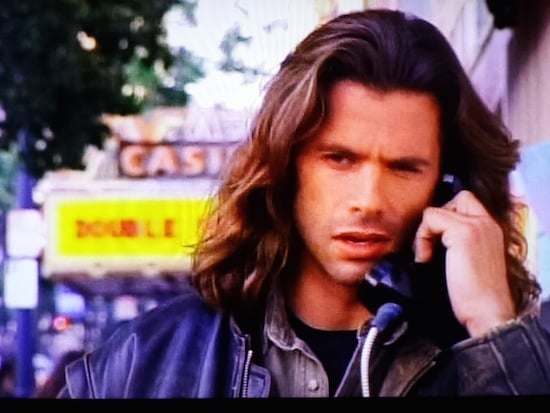

Renegade (1992–97).

Homo Sacer, the sacred man. Or, the accursed man. An obscure figure from the earliest days of Roman law. He’s become quite famous lately, at least in the academy, because of a book by the Italian political philosopher Giorgio Agamben which argues that he is the key to understanding the whole history of states and sovereignty in the West, from Augustus to Auschwitz. He’s like Deep Throat or the One-Armed Man; if you understand the homo sacer, you understand the whole system, and everything it’s capable of.

The homo sacer is a criminal. Anyone can kill him lawfully. But he cannot be sacrificed or take part in sacrifice; that is, he is excluded from the public life of the city. He is an outcast, “a banned man, tabooed, dangerous.” The life of the homo sacer is different than the life of the citizen. It is bare life, subject to anyone’s rule.

The homo sacer is outside the law but made by it. According to Agamben, this paradox can explain everything that has gone wrong in Western history. It is the key “by which not only the sacred texts of sovereignty but also the very codes of political power will unveil their mysteries.”

I have to admit to having some trouble with this. Maybe it’s because I don’t have a good head for philosophy. My mind balks at abstraction. I need something tangible to hang concepts on. And as a historian, I have trouble with concepts unmoored from their temporal settings. It’s been a long time since anyone slaughtered a cock to Apollo. I want to know who a homo sacer would be now, in today’s America.

Then it hits me: Lorenzo Lamas. TV’s Renegade. For those unfamiliar with the epochal USA Network original series, I offer as an introduction the opening voiceover to every episode, spoken over an image of a motorcycle traveling down a lonesome desert road toward a fiery sunset:

He was a cop, and good at his job. But he committed the ultimate sin, and testified against other cops gone bad. Cops that tried to kill him, but got the woman he loved instead. Framed for murder, now he prowls the badlands. An outlaw hunting outlaws, a bounty hunter, a Renegade.

The homo sacer is a renegade. He’s bounty. The man who can be killed but not sacrificed. An outlaw hunting outlaws.

An outlaw, but not a bandit. Bandits aren’t outcasts. They have followers, well-wishers. As the historian Eric Hobsbawm writes, bandits exist in a community; their people think of them “as heroes, as champions, avengers, fighters for justice, perhaps even leaders of liberation, and in any case as men to be admired, helped and supported.” Robin Hood was a bandit. So was Ned Kelly. Jesse James was one, even if he shouldn’t have been.

Outlaws are different. They’re not in society anymore.

In movies we can sometimes see the exact moment when it happens, when the last tie is cut. For Kris Kristofferson in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid it’s the escape from Lincoln. For Faye Dunaway in Bonnie and Clyde it’s when she’s visiting home a last time and her mother says “bye baby” in that impossibly forlorn way. Omar Little in The Wire, it happens around the time he goes to war with Marlo’s crew. By the end, when even children are hunting him, he’s definitely on the other side. For Rod Steiger in Run of the Arrow, it’s when his old Irish mother asks him to stop fighting at the end of the Civil War. They’re in the same frame but they don’t look at each other. He’s already in another place. All he says is, “I hate, momma, I hate.”

A word about Run of the Arrow, Sam Fuller’s preposterously convoluted allegory of the Civil Rights movement, in which Steiger plays on Irishman, O’Meara, so full of hate for Yankees that he has to become a Sioux just to keep killing them. The film happens to contain one of the best dramatizations of the condition of the homo sacer that I know of. The title comes from a Sioux ceremony, an ordeal designed especially for outlaws and renegades. O’Meara is both. The rules are simple; instead of being skinned alive, he can try to outrun a party of braves. He gets a head start of one arrow shot. If he violates the run he will be skinned. If he falls behind at all he will be shot.

Always on the run, always the length of an arrow shot between you and your people. That seems awfully close to the impossible position of the homo sacer to me. Never mind that there is a friendly squaw waiting to hide O’Meara under a buffalo pelt, or that he’s soon to become a lead scout and a favorite of the chief.

Renegades and chiefs aren’t that far apart to begin with. As Agamben points out, the life of the homo sacer is the exact obverse of that of the sovereign. All men can act as sovereigns over the homo sacer; to the king, all men are potentially homines sacri. Both hold the keys of life and death in their hands: the one because no one can touch him, the other because he has nothing to lose.

Or as Omar might say, when you come at the king, you best not miss.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators