10 Best Adventures of 1988

By:

March 30, 2020

Thirty-two years ago, the following 10 adventures from the Eighties (1984–1993) were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture sci-fi adventure The Player of Games. The Glass Bead Game in space? Games, for those lucky enough to belong to the technologically advanced and leisurely Culture, are considered one of humankind’s highest achievements and most worthwhile pursuits; within that context, Jernau Morat Gurgeh is one of the best players of games. Gurgeh, a brilliant, blasé, and not particularly likeable character, is recruited by Special Circumstances — an outfit that does the Culture’s dirty work when it comes to interacting with less-developed galactic civilizations — and tasked with participating in a ritual gaming tournament the outcome of which will determine the players’ social status… and who the Azad Empire’s next emperor will be. (The Azad Empire, BTW, is America: materialistic, exploitative, sexist and racist, pasty and bloated.) Meanwhile, what’s up with the AI drone Mawhrin-Skel, who has been ejected from Special Circumstances? Although we never learn every aspect of “Azad,” an immersive virtual reality game, we get the impression that it’s highly complex and demanding; there are three-dimensional game boards of various shapes and sizes, various numbers of players who can compete or cooperate, and randomness is a factor. Gurgeh discovers that the Azad game is a crucial vehicle for transmitting the Azad Empire’s values to its population… and it’s for this reason that the Culture wants to interfere. As he advances through the tournament, Gurgeh is matched against increasingly powerful Azad politicians, and finally the Emperor himself; will Gurgeh survive the tournament? And even if he does, will the experience infect him with Azadian non-Culture values? Fun facts: The second published Culture novel. A film version was planned by Pathé in the 1990s, but was abandoned. In 2015, Elon Musk named two SpaceX autonomous spaceport drone ships — Just Read the Instructions and Of Course I Still Love You — after AI ships in this book.

- Umberto Eco’s apophenic treasure-hunt adventure Foucault’s Pendulum. A bit punch-drunk after having been required to read too many paranoid manuscripts concerning conspiracy theories about Gnostics, the Freemasons, the Bavarian Illuminati, the Jesuits, the Rosicrucians, the Knights Templar, and Opus Dei, not to mention the Assassins of Alamut, the Ordo Templi Orientis, Cabalists, the Elders of Zion, etc., etc. — Belbo, Diotallevi, and Casaubon cobble together “The Plan,” a satirical, all-encompassing conspiracy theory and intellectual game ultimately concerned with the lost treasure of the Knights Templar. Belbo is a frustrated semiotician and editor at a Milanese vanity press; he and his colleague, Diotallevi, a cabalist, had recruited Casaubon, a student activist and historian of the Knights Templar, to work for them as a freelance researcher. When Belbo is kidnapped by a secret society, it becomes apparent that a real-world secret society will stop at nothing to acquire the (mythical — or is it?) treasure, which may or may not be the Holy Grail, which itself may or may not be a radioactive energy source. The book opens with Casaubon hiding from the society near the titular pendulum in Paris’s Musée des Arts et Métiers. The great pleasure of this text is watching the “Plan” come together via our protagonists’ various absurd, yet somehow utterly convincing, intellectual-literary-computational experiments. Fun facts: Eco founded and developed one of the most important approaches in contemporary semiotics, usually referred to as interpretative semiotics. When asked, after the publication of Dan Brown’s bestselling The Da Vinci Code (2003), whether he’d read it, Eco replied: “Dan Brown is one of the characters in my novel Foucault’s Pendulum, which is about people who start believing in occult stuff…. Dan Brown is one of my creatures.”

- Douglas Adams‘s crime/sci-fi adventure The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul. In Dirk Gently’s second outing, London’s one and only holistic detective is consumed with guilt when his client, a record label executive, is found decapitated; he’s assumed that the man’s ravings about a seven-foot-tall, scythe-wielding monster, and a contract signed in blood, and something about potatoes, were mere delusions. The perpetually broke, intermittently psychic private eye investigates the matter — and in doing so uncovers a pseudo-conspiracy involving (and victimizing) the Norse gods, not to mention an exploding Heathrow check-in counter, a nose-biting eagle, a malfunctioning Coca-Cola vending machine, an I Ching calculator, an attractive American woman, and a god who may have bestowed his powers on a Trump-esque lawyer. All of which are, of course, connected. Can Gently bail Odin, Thor, and the rest of the pantheon out of trouble? Will he ever clean out his refrigerator? Will he get paid? From the sublime to the ridiculous, this might as well be Adams’s motto. Fun facts: Adams first used the mock-portentous phrase “the Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul” in Life, the Universe and Everything to describe the wretched boredom of immortality. Adams began working on a third Dirk Gently story, which he abandoned. He planned to salvage parts of it for a sixth and final installment in the Hitchhiker’s series; however, he never ended up finishing either book. The unfinished MS was published in the 2002 collection The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time.

- Peter Carey’s frontier adventure Oscar and Lucinda. Oscar, a Englishman raised in a fundamentalist sect, becomes obsessive about gambling while at Oxford, then sets out to become a missionary in New South Wales (Australia). Lucinda, an ambitious Australian heiress and compulsive gambler, inherits a glassworks in her native land. The two meet on board a ship headed for Australia; it’s the mid-19th century. After Oscar is kicked out of his vicarage for gambling, he moves in with Lucinda… who bets him that he cannot transport the glass factory from Sydney to a remote settlement hundreds of miles away, then build a church entirely of glass there. This is the “adventure” part of Oscar and Lucinda. It’s an exotic travelogue, in an astonishing landscape; and it’s a strange, compassionate, funny, tragic (love?) story about two intersecting lives. Neither of our eccentric protagonists is particularly sympathetic, though from our perspective we can appreciate their instinctive desire to break from social strictures and structures. Oscar makes some bad decisions; things don’t end as happily and neatly as we might like them to. It’s a terrific read! Fun facts: Winner of the Booker Prize. The film adaptation, directed by Gillian Armstrong and starring Ralph Fiennes, Cate Blanchett, and Tom Wilkinson, was released in 1997. “The thing about Oscar And Lucinda is, it’s not a genre book,” says Charlie Jane Anders. “There’s nothing in it that isn’t explainable through realism. There’s nothing in it that’s speculative. But at the same time, it is a book in which science is incredibly important. Also, there is a lot of magic realism happening on the edges.”

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Xenogenesis sci-fi adventure Adulthood Rites. Thirty years after the events of Dawn (1987), the population of Earth is divided into communities of Oankali (a seemingly benign, tentacled alien species that travels through the universe seeking partner species with whom to “trade” their own genes) and their half-human, half-Oankali offspring, and sterilized human resisters. Akin, the half-Oankali son of Lilith Iyapo, ambivalent protagonist of Dawn, is raised by five parents representing three genders — the Oankali “third sex” is known as the ooloi — and two species. Captured by human resisters, because (for the moment) he looks fully human, Akin finds them as horrifying and as compelling as his mother found the Oankali; for the first time, he finds value in his human side, and learns the value of preserving human culture. (Progressive types are often counseled to try to understand Make America Great Again types, and in large part that is the theme of this book.) Later, Akin becomes an emissary traveling back and forth between Oankali/hybrid and resister villages — and advocates for the resisters to have their fertility restored and to be sent to a terraformed Mars to form their own civilization. But will humankind always self-destruct, if left to their own devices? And will the resisters continue to accept Akin’s assistance once he begins to metamorphose into an adult? Fun facts: This is the second installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy; it is followed by Imago (1989). Nominated for the Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.

- Bruce Sterling‘s sci-fi adventure Islands in the Net. In the near future — the 2020s (!) — economic and political life is dominated by democratized multinational corporations, and everyday life is shaped and misshaped by Net-enabled instantaneous worldwide communications. Yes, this is a cyberpunk novel… but our protagonist, far from being a rebellious young (usually male) hacker, is a married, middle-aged career woman. Laura Webster works for the multinational megaconglomerate Rizome, which stores its data in Granada, Luxemburg, and Singapore; these data havens, however, have been linked to anticapitalist terrorist activity. Laura, her architect husband, and their baby embark on a global tour to restore Rizome’s damaged reputation. When one data haven representative is assassinated (via an armed drone), the story turns into a hunted-man adventure; Laura and her family find themselves hiding out among offshore scientists and artists, the Church of Isis, and agents of rival multinationals. Sticky Thompson, a face-changing terrorist with neurotoxin bacteria in his gut, and Jonathan Gresham, a rogue American journalist involved in a low-tech Tuareg nomad rebellion, are compelling characters. Sterling did a good job predicting wearable tech: Net-connected glasses and watches; and his Net is more like the one we experience today than the semi-hallucinatory, cyberspace version conjured up by William Gibson. Fun facts: “I don’t think any SF prognosis can hold up in sharp detail,” Sterling said in a 2000 interview. “But I would bet that if you took a broad list of near-future 1980s science fiction novels and looked at them in the 2020s, Islands in the Net would seem far less ludicrous than most.” Agreed.

- Alejandro Jodorowsky and Zoran Janjetov’s cyberpunk comic Before the Incal (1988-1995). Once you’ve read The Incal, Jodorowsky and Moebius’s 1980–1988 space opera comic in which bumbling private investigator John DiFool runs afoul of various forces — corrupt government agents, the Technopriests, the alien Bergs, others — seeking a crystal of enormous power, check out this silly but effective prequel. In relatively straightforward installments — Adieu le père (1988), Détective privé de Classe R (1990), Croot! (1991), Anarchopsychotiques (1992), Ouisky, SPV et homéoputes (1993), and Suicide Allée (1995) — set in the Jodoverse’s urban milieu, we encounter a surprisingly with-it, proactive younger version of DiFool. His character develops, from installment to installment, as he investigates the disappearance of missing prostitutes’ children, discovers that big tech, billionaires, the government, the army, and corporate media are secretly in cahoots, and more. True, the female characters here leave much to be desired. But the android “policeborgs,” the body-swapping president, and the disembodied brain which commands a legion of technopriests, are fun. One misses Moebius’s artwork, but Janjetov was selected because his work resembles Moebius’s early, Blueberry-era comics; it’s more gruesome and sexually explicit than Moebius, and that’s OK. Fun facts: Followed by Jodorowsky’ After the Incal (2000, with Jean Giraud), and Final Incal (2008–2014, with José Ladrönn).

- Ben Edlund’s parodic superhero comic The Tick (1988–1993). In 1986, Brockton, Mass., high-school student Ben Edlund created a parodic superhero along the lines of, for example, Megaton Man; or, going back further, Superduperman, as a newsletter mascot for the New England Comics chain of stores. The Tick, a 300-pound, seven-foot-tall doofus whose desire to fight evildoers is admirable but often misguided, is — in his earliest incarnation — an escapee from a mental institution. He’s bugged out. Beginning in 1988, New England Comics would publish a dozen installments, in low-budget black-and-white, of The Tick comic… which was surprisingly complex and awesome, considering the fact that Edlund was still a MassArt student, at that point. The titles tell the tale: e.g., “High Rise Hijinx” (June 1988), “Night of a Million-Zillion Ninja” (December 1988), “Spoon!” (February 1990), “Some Obstacles and a Partial Resolution” (October 1991). The Tick’s sidekick, the hapless Arthur, was introduced in the 4th issue. There have been many superhero parodies, but this one was different: It is impossible not to love the Tick, who is given to issuing garbled, Adam West-esque pronunciamentos about crimefighting. The Tick’s milieu — underappreciated superheroes, hanging out together but not really getting along — is highly entertaining; Edlund would help create a supervillain version for Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog. A high point for low humor. Fun facts: Edlund walked away from The Tick comic after signing a deal to adapt the characters into a Saturday morning cartoon for Fox. The 1994 series, in which Townsend Coleman voiced the Tick and Mickey Dolenz (!) voiced Arthur in the first season, attracted a legion of new fans for the character. Two live-action TV series have also been based on the character; I enjoyed the short-lived 2001 series starring Patrick Warburton and David Burke, haven’t seen the more recent series from Amazon yet.

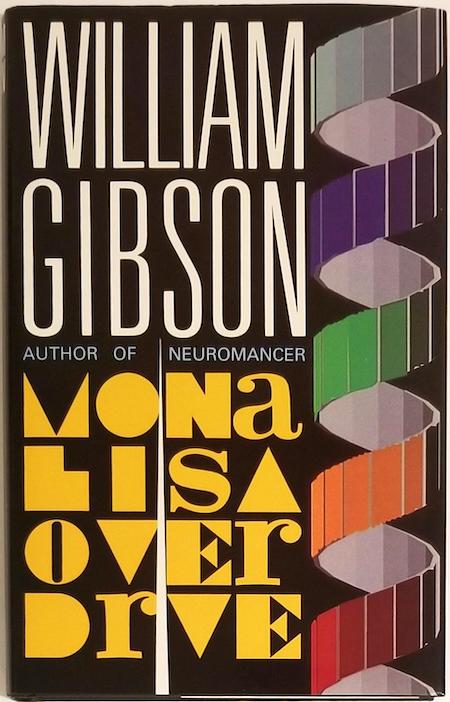

- William Gibson‘s Sprawl sci-fi adventure Mona Lisa Overdrive. Eight years after the events of 1986’s Count Zero: Kumiko, the adolescent daughter of a Yakuza boss, hides out in London with “Sally Shears” (Molly Millions, the knife-fingered mercenary from 1984’s Neuromancer), not to mention a biosoft apparatus that presents as a British child (and which can only be seen by Kumiko); Angie Mitchell (from Count Zero) struggles in the aftermath of a breakdown caused by her Simstim fame, and seeks her missing boyfriend; Mona, an amateur teen prostitute pimped by her nasty boyfriend, is caught up in a crime organization’s attempt to abduct her celebrity lookalike; and the comatose body of Bobby Newmark (the titular protagonist of Count Zero) is cared for by Slick Henry, a Mark Pauline-esque junkyard-dwelling giant-robot artist and car thief who suffers from blackouts. Molly and Angie are the motivating forces, here: they’re looking to force a confrontation and settle the turmoil unleashed by the events of the previous books. Bobby, meanwhile, has become addicted to an Aleph, a Borgesian super-capacity cyber-harddrive that is, essentially, a self-contained world. Will Angie regain the ability to access cyberspace directly, via the biosofts implanted in her head by her father? What is Continuity — the AI that is the most important decision-maker for Sense/Net, Angie’s production company — up to? Will Bobby wake up? Fun facts: Steven Poole wrote in The Guardian that “Neuromancer and the two novels which followed, Count Zero and the gorgeously titled Mona Lisa Overdrive, made up a fertile holy trinity, a sort of Chrome Koran (the name of one of Gibson’s future rock bands) of ideas inviting endless reworkings.”

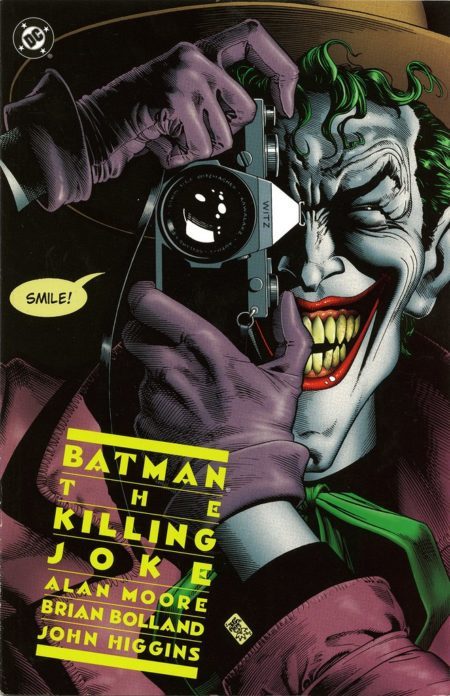

- Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Batman adventure Batman: The Killing Joke. After Frank Miller rebooted DC’s iconic Batman character with The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Batman: Year One (1987), there was just one question left to answer. If Batman hadn’t chosen to find meaning in life — after the random, tragic murder of his parents — by fighting crime, what kind of monster might he have instead become? Alan Moore, who’d fallen out with DC after creating Watchmen (1986–1987), was tempted back the opportunity to explore how Batman and the Joker are, psychologically speaking, “mirror images of each other” (as he’d put it). An unnamed chemical company engineer quits his job to become a stand-up comedian, only to fail miserably. Not only that, his pregnant wife dies in an accident. While participating unwillingly in a burglary at the plant he’s frightened by Batman, and jumps into the chemical waste… which bleaches his skin white and dyes his hair green. Years later, the Joker escapes from Arkham Asylum and attempts to prove that anyone could become a monster… by torturing Commissioner Gordon, and crippling Barbara Gordon. Moore’s Joker story is a nasty piece of work, hard to stomach, but it has proven influential. Fun facts: The Killing Joke was awarded an Eisner Award, for best graphic novel of 1988. Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan have acknowledged the graphic novel’s influence on their respective Batman movie adaptations; Todd Phillips has stated that the Joker’s descent into madness after an unsuccessful career as a stand-up comedian in The Killing Joke helped inspire his 2019 film Joker.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.