10 Best Adventures of 1914

By:

April 15, 2019

One hundred and five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Teens (1914–1923) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

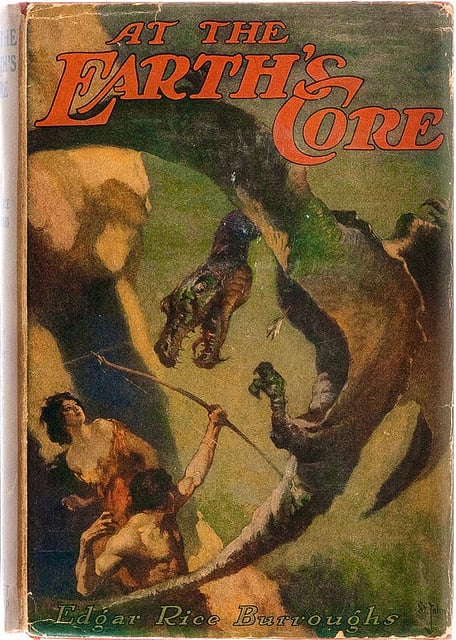

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar sci-fi adventure At the Earth’s Core (serialized 1914; in book form, 1922). Thanks to a futuristic “iron mole” device invented by an eccentric engineer friend, the intrepid David Innes is the first to discover that the Earth is hollow. At the planet’s center is Pellucidar, a land — lit by a miniature Sun — in which warring stone-age human tribes are dominated by the Mahars, flying reptiles who are intelligent and possessed of telekinetic abilities. (Gravity, we learn, is an attraction towards planetary crust, not planetary core; and time doesn’t work the way we imagine.) Can Innes battle dinosaurs and proto-humanoid Sagoths (the Mahar’s slaves), rescue the lovely Dian, lead a revolt against the Mahars, steal their Great Secret, establish a peaceful kingdom… and somehow return to the planet’s surface? An entertaining read, though seriously marred by the racist suggestion that humans of color are, above or below, less evolved than other humans. Fun facts: The first of several Pellucidar adventures, including Pellucidar (1915), Tanar of Pellucidar (1929), and Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929). H.P. Lovecraft was a fan; his 1931 adventure At the Mountains of Madness includes the Shoggoths, a race of humanoids enslaved by the Elder Things.

- Inez Haynes Irwin’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Angel Island. Shipwrecked on an uncharted island, five men encounter five winged women, rebels from their tribe who’ve decided to fly south instead of north. Frustrated by how aloof and skittish the women are, the men clip the women’s wings. At first, four of the five women enjoy the attention — all but one, their leader, Julia — and marry four of the men. However, the domesticated women soon realize that married life is a form of servitude, and they lament their lost freedom. When they bear children (mostly wingless boys) and discover that the one winged girl-child will also have her wings clipped, the domesticated women take a stand. They demand rights for women — after which things change on the island. The women’s wings are no longer clipped. Julia gets married: symbolically, her child is a winged boy. Fun fact: Inez Haynes Irwin, who’d been active in the suffragist movement, was fiction editor of the left-wing periodical The Masses.

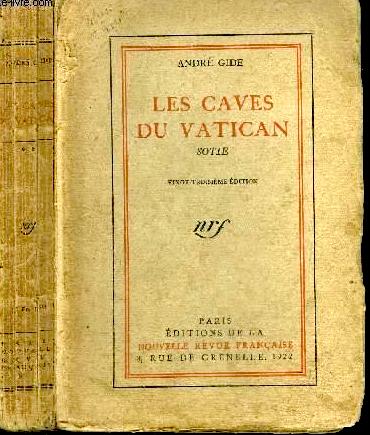

- André Gide‘s picaresque Les caves du Vatican (in English: Lafcadio’s Adventures, The Vatican Catacombs, other titles). Gide described this antic, Shakespearean comedy-style yarn, set in 1890s Paris and Rome, as a sotie — that is, a satirical play exposing humankind’s foolishness. Bourgeois morality and complacent religiosity do take a beating, here. Three of our five protagonists are Anthime, a pedantic freethinker and scientist living in Rome, who experiences a religious conversion; Julius, a smug, middlebrow Parisian novelist hoping to win a Nobel prize by writing a crime novel about an acte gratuit — an action that is unmotivated; and Amédée, a devout, naive Catholic — all of whom are brothers-in-law, and all of whom become entangled to various degrees in a con game, the victims of which are led to believe that the Pope (Leo XIII, at the time) has been kidnapped, replaced with an imposter, and incarcerated underneath the Vatican. Our fourth protagonist is Protos, a con man who poses as a Catholic priest raising money to rescue the true Pope from the Freemasons; and our fifth is Lafcadio, a teenaged would-be ubermensch who reads nothing but adventures like Aladdin and Robinson Crusoe, and whose goal in life is to perform an acte gratuit — whether for good or ill. When Lafcadio, whom we discover is the illegitimate half-brother of Julius and a former schoolmate of Protos, encounters Amédée, who has headed out to singlehandedly rescue the Pope, who will survive the encounter — the hero or the antihero? Fun facts: First serialized January–April 1914 in La Nouvelle Revue Française. Gide was among those few French writers of the early 20th century who took inspiration from pulp fiction, as a rebuke to the earnestness of highbrow European fiction. A few years later, André Breton would write, to fellow absurdist litterateur Tristan Tzara, “You can’t imagine how much André Gide is on our side.”

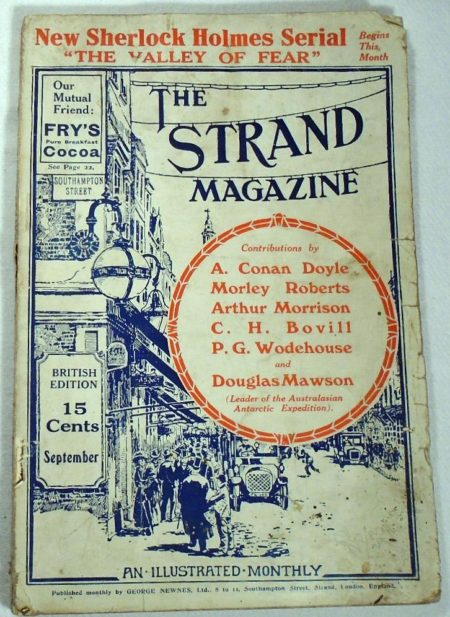

- Arthur Conan Doyle‘s Sherlock Holmes adventure The Valley of Fear. The fourth and final Sherlock Holmes adventure is loosely based on the Molly Maguires, an Irish secret society known for their sometimes violent activism among Irish-American and Irish immigrant coal miners in Pennsylvania, and Pinkerton agent James McParland, who infiltrated the Molly Maguires. Holmes receives a cipher message from a turncoat agent of Professor Moriarty, the machiavellian criminal mastermind whom nobody but Holmes believes to be evil. After cracking the cipher, Holmes and Watson investigate the murder of John Douglas of Birlstone Manor House, in Sussex. The dead man’s forearm is branded with a curious design, a triangle within a circle; and he had been known to speak of “The Valley of Fear,” perhaps a place in America from which he’d fled. Watson finds the dead man’s widow and his best friend laughing merrily in the garden. Not all is as it seems, with the murder, and once Holmes gets to the bottom of it, he learns that Douglas was once a Pinkerton detective in Chicago, who’d infiltrated a murderous gang in Chicago, and brought them to justice. Although Holmes doesn’t appear in this back-story, it’s exciting stuff. Fun facts: The story was first published in the Strand Magazine between September 1914 and May 1915; it was published in book form in 1915. While one might expect to sympathize with the Irish gang in their struggle against the mining companies, Douglas’s story portrays them as ruthless criminals who exploit both workers and wealthy capitalists alike.

- H.G. Wells’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The World Set Free. Building on the recent discovery that “the atom, that once we thought hard and impenetrable, and indivisible and final and — lifeless — lifeless, is really a reservoir of immense energy,” Wells conjures a 1950s England in which clean, efficient atomic engines have transformed life for the better. Alas, a world war breaks out, in which atomic bombs wipe out the world’s great cities. Worldwide civilization is on the brink of collapse, when a conference of enlightened monarchs, presidents, powerful journalists, and scientists gathers in order to establish a peaceful one-world order. When one Kissinger-like figure begins to strategize about maintaining national autonomy and monarchical authority within this utopian world government, another character shuts him up with one word: “BANG!” Fun fact: The astrophysicist Leó Szilárd, who worked on the Manhattan Project, claimed that The World Set Free helped him conceive of the nuclear chain reaction. See my essay on The World Set Free and Wells’s two books of floor games for children.

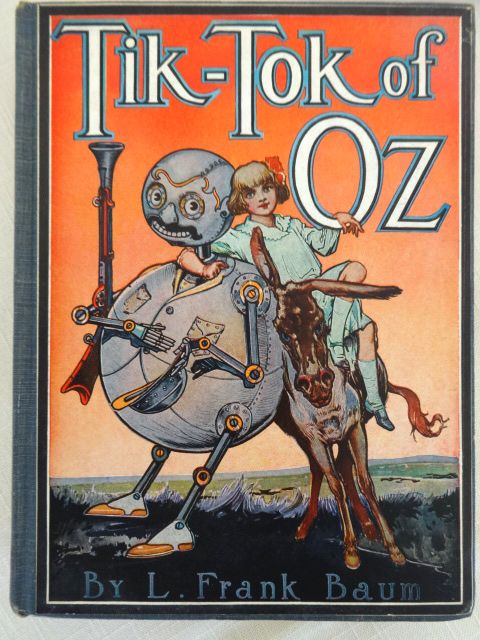

- L. Frank Baum‘s Oz fantasy adventure Tik-Tok of Oz. Tik-Tok, a “Patent Double-Action, Extra-Responsive, Thought-Creating, Perfect-Talking Mechanical Man Fitted with out Special Clock-Work Attachment,” made his début in Ozma of Oz (1907). In the eighth Oz book, the plot of which Baum based on his 1913 play of the same title, Tik-Tok joins an anti-Nome King strike force composed of the principled hobo Shaggy Man and the cloud fairy Polychrome, both of whom first appeared in 1909’s The Road to Oz; the newly plucked Rose Princess Ozga, a cousin of Ozma’s; the small army of Queen Ann Soforth of Oogaboo; and Betsy Bobbin and her mule Hank — a last-minute substitute for the characters Dorothy Gale and Toto, who were contractually unavailable to Baum for theatrical purposes. When the Nome King sends this ragtag army through his Hollow Tube to the jurisdiction of Tittiti-Hoochoo, the powerful jinjin sends them right back again with an Instrument of Vengeance: Quox, a less-than-impressive dragon. The battle is on! Will the Shaggy Man find his missing brother — and if so, can he free him from the Nome King’s spell? Fun facts: The endpapers of the first edition of Tik-Tok of Oz feature the first maps printed of Oz and its neighboring countries. Unfortunately, the map of Oz was drawn backwards, which has caused confusion ever since.

- Eugene Manlove Rhodes’ Western adventure Bransford in Arcadia. Rhodes’ first short novel, Good Men and True (1910), introduced us to the literature-loving cowboy Jeff Bransford, who after witnessing an attempted murder in El Paso is kidnapped by a wealthy politician and businesssman. In that book’s sequel, set in the Tularosa Basin within the Chihuahuan Desert, east of the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico, Bransford is arrested for a bank robbery that involved a near-fatal shooting… but he can’t reveal his alibi, because he was keeping company with Ellinor, a respectable young woman — and their meeting was unchaperoned! Unable to account for his whereabouts at the time of the robbery without compromising the reputation of his lady friend, Bransford instead makes a dramatic escape and flees town with a posse in hot pursuit. Then, like Richard Hannay in John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, which would be serialized the following year, Bransford disguises himself and brazenly offers to help his pursuers apprehend their quarry. Later, he will also attend a masked ball in disguise — while wearing a football uniform! The “Arcadia” of the title is a hacienda run by a decent, honest, hard-working Mexican family; unlike many adventure novels of this period, Rhodes’s is unusually free of racial stereotyping. Will Bransford ever be cleared of this crime? And if so, what will happen with the lovely, virtuous Ellinor? A thrilling, and amusing yarn. Fun facts: Rhodes moved to New Mexico with his family as an adolescent; there, he became an accomplished horseman, stonemason, and road builder. Although he spent two decades in the state of New York, he often wrote about New Mexico; it was he who first dubbed it the “Land of Enchantment.”

- Sax Rohmer‘s crime adventure The Sins of Séverac Bablon. The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, Sax Rohmer’s first novel, and an immediate success, was published in 1913; the following year, he published this yarn about another mysterious “Eastern” villain — Severac Bablon, a half-Jewish extortionist and blackmailer who targets London’s wealthiest businessmen. Offensive? Yes and no. As it turns out, Bablon is a Robin Hood-esque figure who seeks to repair the reputation of Jewish people, among anti-Semitic Britons, by “persuading” wealthy Jews to donate large sums of money to the poor, and to fund England’s upcoming war effort rather than loaning money to England’s enemies. But isn’t it offensive to portray Jews as miserly financiers? Yes, for sure — but Rohmer’s story depicts a variety of wealthy Jews, some of whom are already compassionate and patriotic. Even Bablon’s less generous victims aren’t particularly miserly — they’re libertarians, basically. The story is narrated by Tom Sheard, a Fleet Street reporter and friend of Bablon’s who comes along for the ride. Bablon is able to command the loyalty of Jews around the world, in his quixotic struggle; and it is this — the notion that Jews form a secret nation-within-nations — that is the most offensive aspect of the story. In the end, however, the reader roots for Bablon, who one suspects must have been an influence on Leslie Charteris’s Robin Hood-like criminal character, The Saint. Fun facts: Rohmer, the son of Irish immigrant parents who moved to London in 1886, had an ambition to serve in the Civil Service in the East. On failing the entrance examination, he instead began writing songs and fiction.

- Raymond Roussel’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Locus Solus. Invited to Locus Solus, the suburban estate of the reclusive, fabulously wealthy French scientist Martial Canterel, a group of his colleagues are introduced to strange and complex inventions and oddities: a wind-powered paving bot, which constructs elaborate mosaics of human teeth; the preserved head of 18th-century revolutionary Danton, which speaks when stimulated by a hairless cat; a vast aquarium in whose “aqua-mican” terrestrial mammals can breathe (hm — a similar appratus had appeared in Gustave Le Rouge’s 1909 sci-fi adventure La Guerre des Vampires); a doctor who painlessly removes fingernails and replaces them with mirrors; and so forth. Within an enormous glass cage, eight zombies whom Canterel has revived (thanks to his invention, “resurrectine”) act out the most important incidents of their lives — over and over again, sometimes in the company of their still-living family members! Behind some of Canterel’s artifacts lie strange and disturbing stories (and stories within stories); behind others, delightfully surreal ones. We’re also treated to sober explications of the technology making each exhibit possible. It’s a far-out, macabre wunderkammer, and a philosophical novel exploring what Adorno and Hortkheimer would later call the dialectic of Enlightenment — i.e., the irrationality of science, the logic of obsession. Fun fact: Roussel composed Locus Solus using eccentric, punning guiding principles — explained in his posthumous text, How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935) — that would influence later experimentalists. John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, James Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch edited a 1960s journal called Locus Solus (after Roussel’s novel), which has been called the New York School of poets’ manifesto.

- G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Flying Inn (1914). When a British politician, Lord Ivywood, sets out to Islamize Great Britain — so that he can enjoy the benefits of polygamy — he enlists the assistance of the nation’s “smart set,” who are all too eager to embrace trendy, Eastern “fads.” Among other changes, Ivywood pushes through laws requiring that alcohol only be sold by an inn displaying a sign… and banning inn signs. In an act of populist defiance, Captain Patrick Dalroy, a hard-drinking Irish giant, and Humphrey Pump, dispossessed landlord of one of the shuttered English inns, take to roaming the countryside with a cart (later, a motorcar) full of rum, a tavern sign, and an enormous wheel of cheese. Meanwhile, we discover that Ivywood is bent on destroying Christianity and Western culture… and that he is smuggling a Turkish army into England! Chesterton, alas, is the original pamphleteer for Brexit; this novel is an Islamophobic lament for an England besieged by theosophists, vegetarians, and xenophiles. It is offensive in its refusal to take other cultures seriously… though the poetry about England and weird drinking songs are pretty entertaining. “Tea, although an Oriental,/Is a gentleman at least;/Cocoa is a cad and coward,/Cocoa is a vulgar beast.” Fun fact: According to some critics, Chesterton makes readers complicit in an architecture of unquestioned privilege and received prejudice. Others see it as a folksy riposte to the political left’s attraction to the quasi-mysticism of the East. You decide!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.