Listen, Hollywood! (7)

By:

July 22, 2019

One in a series of 10 posts suggesting novels (from Josh Glenn’s BEST ADVENTURES series) that really ought to be adapted for the big screen.

G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Napoleon of Notting Hill appeared on my list of the Best Adventures of 1904.

Elevator pitch:

In the not-too-distant future, Europe has achieved hegemony over the rest of the world. The result is “a great cosmopolitan civilization,” as one character puts it, “one which shall include all the talents of all the absorbed peoples.” There are no longer any soldiers or policemen; there is no war or crime. Everything functions efficiently… at the cost of particularism, creativity, and the kinds of scientific and technological breakthroughs driven by capitalist competition. England has abolished democracy, which was inefficient; whenever a monarch dies, a new one is chosen randomly — their role is strictly decorative. When Auberon Quin, a prankster, is appointed king, he declares that London’s neighborhoods shall henceforth be independent city-states, each with their own colorful insignia and military units armed with swords and halberds. The city becomes a theme park, and each Londoner has a role to play in a city-wide LARP. Fun!

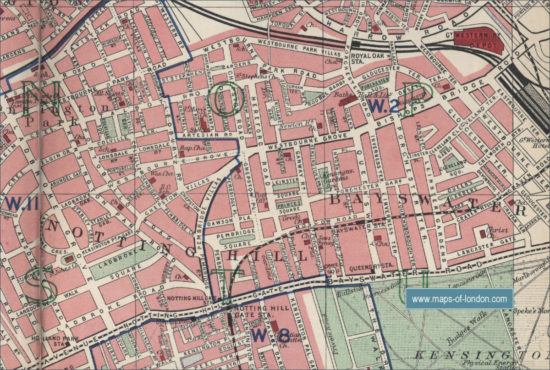

Ten years later, however, the youth of London’s Notting Hill neighborhood — who’ve grown up playing this medieval fantasy game — take it all too seriously. They’re zealously proud of Notting Hill’s banners, songs, and rituals; their militia trains ferociously; they have developed local jargon, songs, rituals. When London’s utopian functionaries — attempting to make the movement of goods and people more efficient — plan to raze a dusty, overlooked street in Notting Hill, a riot breaks out. Anthony Wayne, leader of Notting Hill’s militia, and his comrades devise brilliant urban guerrilla tactics to fight off the developers. (Think of Timothy Hutton, Sean Penn, and Tom Cruise in Taps; not to mention Patrick Swayze and Charlie Sheen in Red Dawn.) Other local militias are brought in to subdue Notting Hill, but to no avail — and the fighting threatens to engulf London!

First act

Chesterton’s novel presents us with two powerful responses to the neo-totalitarian dullness of an achieved utopia. The first response is a satirical one.

The citizens of utopian London (in the year 1984) are afflicted, we learn, with a “vague and somewhat depressed reliance upon things happening as they have always happened.” People dress in a “sombre and hygienic manner” — that is to say, in the kind of functional uniform that suggests a social order without political, cultural, or economic distinctions. Note that the utopian London of the near future isn’t particularly sci-fi; although the city is poverty- and crime-free, eco-friendly, and so forth, we’re not going to see hover cars or jetpacks here. One key difference, though, is that London is tasteful: advertising, fashion, media are subdued. Chesterton raises the same issue that Ursula K. Le Guin makes in The Dispossessed: In an egalitarian, non-consumerist society, if there’s no material incentive for inventors and innovators, why would anything ever change? Everyone is too content to strive.

Democracy has been abolished; instead, we have a “dull popular despotism,” a managerial monarchy, selected by randomizing algorithm. Auberon Quin is a utopian functionary; but unlike his colleagues — we also meet Lambert and Barker — he is, at heart, ironical. He can’t take utopia seriously. Its dull efficiency offends his sensibilities. He worries that the decline of imagination and creativity have stultified not just the culture but scientific and technological advances, the progress of humankind.

Lambert, by the way, is a romantic type; while Barker is all business. This distinction becomes important, later in the story.

Quin is a Dadaist or Situationist avant la lettre: “I am a man whose soul has been emptied of all pleasures but folly.” In fact, at the very moment that he is randomly appointed king, he is attempting to shock his strait-laced colleagues Barker and Lambert by standing on his head and moo-ing in a public park. Amusing camera angle: The utopian functionary sent to inform Quin that he is king is viewed upside-down.

King Auberon doesn’t intend to subvert utopia entirely; he just wants it to be less dull. So he sets about opposing the stultification of everyday life through japery. He is inspired by an encounter with an eccentric he meets — the former president of Nicaragua, who insists upon wearing his military medals and Nicaragua’s flag colors — King Auberon declares that “Something went from the world when Nicaragua [and all other countries, now subsumed into the homogenized world state] was civilized.” He is also inspired by a young red-headed boy he encounters in Notting Hill, who is playing “King of the Castle” with a wooden sword and a paper cocked hat. Aha!

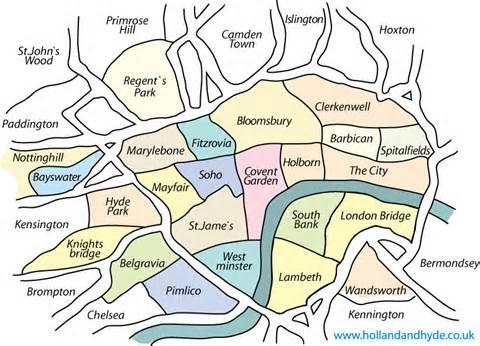

Auberon sets about instituting “a revival of the arrogance of the old medieval cities applied to our glorious suburbs. Clapham with a city guard. Wimbledon with a city wall. Surbiton tolling a bell to raise its citizens. West Hampstead going into battle with its own banner.” His idea of a supreme joke, in modern, ultra-civilized, functional and efficient world state, is to revive “a keener sense of local patriotism in the various municipalities of London.” He invents all sorts of (silly) legends for each neighborhood — Knightsbridge is named after three knights who defended a bridge, etc. — and suburb; he invents coats of arms and local color schemes, and local rallying cries.

By the end of Act One, ten years after Quin’s accession to the throne, London will look quite different. The city’s municipalities now have unique banners and coats of arms and rallying cries; they have walls; they have troops of guardsmen who bear swords and halberds. There are ceremonies, military exercises, official openings and closings of each city’s gates. Older Londoners are mostly entertained by this folly — Auberon was correct in anticipating how bored they’d become of cosmopolitan universalism, how nostalgic they were for local particularism. He’s made his subjects amused and happy.

It’s all a gag, to King Auberon. But the second powerful response to the neo-totalitarian dullness of an achieved utopia, for Chesterton, is faith. Like satire, faith is a powerful bulwark and corrosive agent against the scientific determinism of the fully efficient world state. The little red-headed boy — who will grow up to be Notting Hill’s revolutionary leader Anthony Wayne, is a man of faith.

Wayne takes King Auberon’s neo-medieval caprice seriously. As an impressionable child, he saw his childish fantasy — each neighborhood builds a medieval city wall, and creates a town guard armed with swords and halberds, and wearing a particular color scheme — come true. He grows up to lead the Notting Hill militia; he studies medieval military tactics; he immerses himself in Notting Hill particularism. His elders think he’s cracked, a little too earnest about King Auberon’s Ye Olde England caprice. But Wayne’s contemporaries — the bored youth of Notting Hill — take him quite seriously. He is their Arthur; they are his knights of the Round Table.

A note about Wayne and his friends: In a way, this is a movie about Brexit in a microcosm — Notting Hill represents “little England,” caught up in a fantasy about a lost, past greatness… and determined to turn back the clock, no matter what the cost. But whereas Brexit is also about xenophobia and racism, I’d suggest that Wayne’s cadre of loyalists be depicted as a multicultural group of young Londoners, men and women — who represent the cosmopolitan world state of the near future. For that matter, Wayne doesn’t need to be a male character. Instead of a King Arthur Figure, perhaps she is a Joan of Arc.

Also: Wayne doesn’t need to be a square-jawed hero type. In Chesterton’s book, he is rather awkward and geeky. Although, in the end, he turns out to be not only a brilliant tactician but a pretty powerful fighter, as well.

Remember, the context of the drama here is a utopian one: These young people haven’t known poverty, discrimination, social injustice. They’ve grown up in a Gesellschaft — an impersonal, bureaucratic, mechanical society; what they long for is a Gemeinschaft — an organic, traditional, affectual community. The pathos of this movie is that we sympathize with these protagonists, even though their actions threaten to destroy utopia; they are the barbarians sacking Rome.

Act One should move quickly through ten years — showing us the success of King Auberon’s satire… and the simultaneous development of the forces of faith. We’ll switch back and forth between fun, frivolous scenes of Londoners decked out in increasingly ornate and colorful medieval costumes, enjoying the respite from utilitarian dullness. Quin pretends to take the history of each neighborhood and suburb seriously, but he’s making it up as he goes along. The residents of Lavender Hill must wear purple; the residents of Parson’s Green must wear green “shovel hats” (clergymen’s felt hats with broad brims); etc. He considers North Kensington a semi-arctic neighborhood, and designs their symbol and clothing to be vaguely Russian. He appoints Lord High Provosts of each neighborhood, and decrees that they must be accompanied everywhere by heralds with trumpets — which is very inconvenient, for these men, and a source of amusement for everyone else.

Wayne and his Notting Hill knights, meanwhile, are growing up to be tough, capable young men and women who know every inch of their neighborhoods — and who train to defend Notting Hill in deadly earnest, as though it truly were an independent kingdom. “Thenceforward the fanciful idea of the defence of Notting Hill in war became to him a thing as solid as eating or drinking or lighting a pipe. … Two or three shops were to him an arsenal; an area was to him a moat; corners of balconies and turns of stone steps were points for the location of a culverin or an archer.” He and his friends are young adults playing a child’s game — but because they’re doing so within the context of King Auberon’s decreed medieval game, they’re not considered childish. The citizens of Notting Hill are proud of how seriously Wayne and his knights take the game.

When the original Lord High Provost of Notting Hall dies, Wayne succeeds to the post. The bottom line, about the adaptation of The Napoleon of Notting Hill: It’s a thrilling drama about young people engaged in urban guerrilla warfare against overwhelming odds; they triumph — for a while — because of street smarts and tactics. So the first act of the movie should feature plenty of training, drilling, and other seemingly absurd preparation for combat in a world where there is no longer war, crime, or strife of any kind.

Second act

King Auberon receives delegations from North Kensington, Bayswater, South Kensington, and West Kensington. The Lord Provosts of these neighborhoods — including his former colleague, Barker (South Kensington) — are bedecked in their medieval finery, and attended by heralds and men-at-arms. Quin loves the spectacle, the game. They’ve come to complain about Adam Wayne, who refuses to allow a road to be built through Notting Hill. It’s a colorful, absurd spectacle — which is just the way Quin likes it. Then Wayne arrives with his knights, bedecked in red and gold, carrying a lion banner. They aren’t kidding around: “They marched and wheeled into position with an almost startling dignity and discipline.” Wayne pays homage to the king, throwing his sword on the floor — startling everyone. Quin immediately adores Wayne, because he thinks he’s the only other Londoner as fond of this medieval joke as he is.

Note that Barker, in particular, barely pays lip service to Quin’s medieval foolishness. His costume is perfunctory. He doesn’t speak in a flowery way. The whole thing seems stupid to him.

Wayne proclaims that he refuses to permit the road to be built, not only to defend Notting Hill from being disrupted, but because “I fight for your royal vision, for the great dream you dreamt of the League of the Free Cities.” King Auberon finally realizes that Wayne is in deadly earnest; and Wayne realizes that it was all a joke to Quin. Wayne speaks eloquently of what Notting Hill means to him, and Quin begins to fall under his spell. Wayne argues that it’s precisely in this disenchanted modern world that one’s neighborhood becomes worth fighting and dying for: “If… there are no gods, and the skies are dark above us, what should a man fight for, but the place where he had the Eden of childhood and the short heaven of first love?”

Wayne returns to Notting Hill, and begins rallying its residents to his cause. In Chesterton’s novel, there is a goofy aspect to this process — because Wayne insists upon speaking to grocers, toy shop owners, and pharmacists as though they were wonderful medieval characters — and they don’t know quite how to respond. The toy shop owner, it turns out, has built a scale model of Notting Hill in his back room, and — as a childish hobby — has worked out plans for its defense against invasion. I’m not sure that any of this needs to be retained for the movie adaptation… but maybe?

Wayne and his comrades plan a defensive campaign — the details of which will be revealed to us as their plan unfolds. For the movie, we can come up with all sorts of ideas. In the novel, since London of 1984 still uses horse-drawn cabs, the first maneuver involves sending little boys out around the city to take cab-rides back to Notting Hill — where the cabs are turned into bulwarks, blocking key streets, and the horses are recruited for a cavalry.

The Lord Provost of North Kensington — a businessman named Buck — decides to nip this foolishness in the bud. With King Auberon’s grudging permission, he sends a troop of six hundred halberdiers into Notting Hill, to capture Wayne. Auberon is torn: He loves how seriously Wayne takes the medieval LARP… yet at the same time, he never intended for warfare to break out because of it. The halberdiers — wearing the colorful costumes of North Kensington, Bayswater, South Kensington, and West Kensington — assemble at the foot of Holland Walk and march up it, led by Buck. The halberdiers of the other neighborhoods have not taken their drilling at all seriously; they’re having a lark.

The king follows, and picnics in Holland Park while waiting to hear about Wayne’s demise. Dramatically, Wayne’s troops drive off the invaders — we don’t see the battle (in the book), but hundreds of bloodied and tattered halberdiers come flooding through Holland Park in full retreat. Wayne and his two hundred red-coated halberdiers, some mounted on captured horses, pursue them.

In the movie, I’d imagine we’d want to show this happening; in the book, it is described by Buck in retrospect. The invading force doesn’t know the layout of Notting Hill; the defenders ambushed them — picked them off as they advanced, then sprung a trap on Portobello Road. Barker — Wayne’s old colleague, now provost of South Kensington — makes the point that Wayne has brought back a certain “atmosphere” which everyone thought had vanished from the earth. Buck and Barker determine that they must attack Notting Hill again, but in the proper spirit — the medieval spirit. For this, they need Lambert — Quin’s other old colleague — whose romanticism will make him a perfect military leader for this situation.

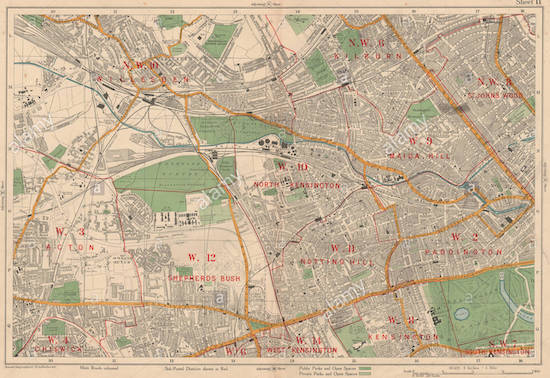

The invaders post soldiers at the nine entrances to Notting Hill. Two hundred purple North Kensington soldiers under Buck march up Ossington Street; two hundred more march up Clanricarde Gardens. Two hundred yellow West Kensingtons attack (led by Lambert) from Pembridge Road. Two hundred more North Kensingtons attack from the eastern streets. Two detachments of yellows enter by Westbourge Grove. Two hundred green Bayswaters (led by their provost, Wilson) come down from the north through Chepstow Place, and two hundred more through the upper part of Pembridge Road. Their flaw is thinking like businessmen — which is what they are. They believe that superior numbers alone can win the day.

The only preparations we see Wayne’s forces making is painting their swords and halberds black, for some unknown reason. The attack comes at night. Wayne’s forces douse all the streetlights. The invaders lose their bearings, stumble about. Notting Hill forces attack: “The invaders were hewn down horribly with black steel, with steel that gave no glint against any light.” It’s a massacre.

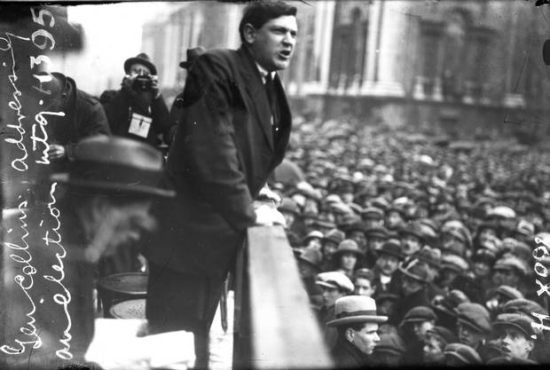

NOTE: The Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins, who was a teenager when this book was published, greatly admired The Napoleon of Notting Hill. It remained a favorite book throughout his life — because of Chesterton’s anti-imperialist message, and because of his vivid recounting of guerrilla warfare in the streets of London.

Third act

In Chesterton’s book, London isn’t particularly affected by these goings-on; Wayne’s bloody victories are regarded as local riots. A siege is set up around Notting Hill. King Auberon crosses the siege line in order to see for himself what’s happening in the neighborhood. He becomes an eyewitness to the final battle of this war.

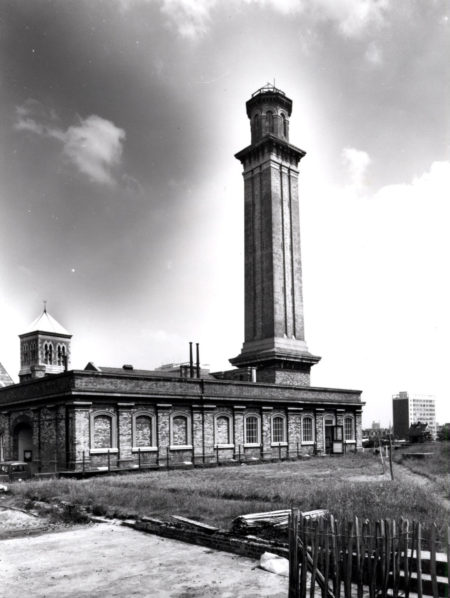

The invaders attack again. Lambert’s forces drive Wayne’s forces to a last stand around the Waterworks Tower on Campden Hill. (Note that in the 1970s, this impressive Italianate tower, built in the late 1840s, was demolished by developers to make way for ghastly apartment buildings… which were themselves later replaced by pretentious “Georgian-esque” townhouses. Exactly the sort of thing that Wayne is fighting against….)

Wayne kills the heroic Lambert — not without paying him tribute. And just when all seems lost, he captures the tower and threatens to open the reservoir and flood the valley. The vast army of South Kensingtin, who will be drowned, surrenders.

Notting Hill becomes an independent city-state — not merely as part of Quin’s Ye Olde England game, but in fact. I imagine that this is where the movie would end. The novel, however, takes us forward another ten years. London now has truly returned to a kind of medieval way of life. Enormous bronze and steel gates guard the entrances to Notting Hill. The shopkeepers wear medieval garb; there are guilds.

King Auberon — now an elderly man — encounters his old colleague Barker, who was once so cynical and dismissive of the medieval game. Now he’s fully decked out in medieval finery, speaks in a flowery way, and he (along with Buck, equally medieval and flowery) is planning the revenge of North and South Kensington upon Notting Hill. Other cities join their attack — Battersea, Putney, etc. They are impossibly colorful — Paddington Green is represented by “rude clans,” Shepherd’s Bush by men wearing fleeces and toting spears. Quin is entranced by how improved Londoners are. “It is not all having plumes; it is also having a soul in one’s daily life.”

Wayne ends up killing both Barker and Buck, but he is defeated. He and Quin go wandering off together, their mission in life completed. “Between us [the fanatic and the satirist] we have remedied a great wrong. We have lifted the modern cities into… poetry.” That is to say, they have re-enchanted the disenchanted modern world.

You know what the fellow said – in Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock. — Orson Welles as Harry Lime, in The Third Man

Final notes:

Chesterton, best known today for his amusing Father Brown mysteries, was a Catholic convert who scorned Edwardian England’s social and political progressivism. He argued — wittily, paradoxically — that every man should adhere to an orthodoxy, and that traditional virtues are best. His 1908 masterpiece, The Man Who Was Thursday, suggests that rebels are nihilistic sophists, while Christians are the true rebels; and his 1914 sci-fi novel, The Flying Inn, suggests that the fad among intellectuals for Eastern philosophy posed an existential threat to the West. GKC was, in short, the original internet troll. In The Napoleon of Notting Hill, his debut novel, Chesterton savages the post-political brand of utopianism that H.G. Wells — his great science fiction novels behind him, by the early 1900s — was then promoting.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill offers a terrific concept: medieval-style warfare breaking out in a utopian future London! Just think of the spectacle. It’s amusing; it’s tragic. It will appeal to a broad moviegoing audience, particularly those who instinctively agree with Harry Lime about the value of strife. Hollywood, we should do this.

But what of Chesterton’s trollish politics, you ask? I suggest that we take inspiration from anti-anti-utopian sci-fi (to use Fredric Jameson’s coinage) by the likes of Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. Le Guin, even Iain M. Banks. Dick, Le Guin, and Banks are sympathetic to utopian goals such as the end of war and social injustice, and the overcoming of racism and sexism, while Chesterton is not. However, like these later, more progressive sci-fi authors, Chesterton offers a warning about the unintended consequences of utopia: thought control, coercion, the privileging of the group over the individual, the stultifying of imagination and creativity. He’s a troll, but we can adapt his witty, thrilling novel into a non-trollish movie.

LISTEN, HOLLYWOOD: Michael Innes’s FROM LONDON FAR | P.G. Wodehouse’s LEAVE IT TO PSMITH | Peter Dickinson’s CHANGES TRILOGY | Robert Heinlein’s GLORY ROAD | Poul Anderson’s THE HIGH CRUSADE | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s TARZAN AND THE FOREIGN LEGION | G.K. Chesterton’s THE NAPOLEON OF NOTTING HILL | Michael Innes’s THE JOURNEYING BOY | Alfred Jarry’s EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN | André Gide’s THE VATICAN CAVES [LAFCADIO’S ADVENTURES].

Also see Josh Glenn’s SHOCKING BLOCKING series: It Happened One Night (1934) | The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) | The Guv’nor (1935) | The 39 Steps (1935) | Young and Innocent (1937) | The Lady Vanishes (1938) | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) | The Big Sleep (1939) | The Little Princess (1939) | Gone With the Wind (1939) | His Girl Friday (1940) | The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946) | The Asphalt Jungle (1950) | The African Queen (1951) | A Bucket of Blood (1959) | Beach Party (1963) | For Those Who Think Young (1964) | Thunderball (1965) | Clambake (1967) | Bonnie and Clyde (1967) | Madigan (1968) | Wild in the Streets (1968) | Barbarella (1968) | Harold and Maude (1971) | The Mack (1973) | The Long Goodbye (1973) | Les Valseuses (1974) | Eraserhead (1976) | The Bad News Bears (1976) | Breaking Away (1979) | Rock’n’Roll High School (1979) | Escape from Alcatraz (1979) | Apocalypse Now (1979) | Caddyshack (1980) | Stripes (1981) | Blade Runner (1982) | Tender Mercies (1983) | Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983) | Repo Man (1984) | Buckaroo Banzai (1984) | Raising Arizona (1987) | RoboCop (1987) | Goodfellas (1990) | Candyman (1992) | Dazed and Confused (1993) | Pulp Fiction (1994) | The Fifth Element (1997) | Nacho Libre (2006) | District 9 (2009).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.