RADIUM AGE ART (1910)

By:

April 14, 2024

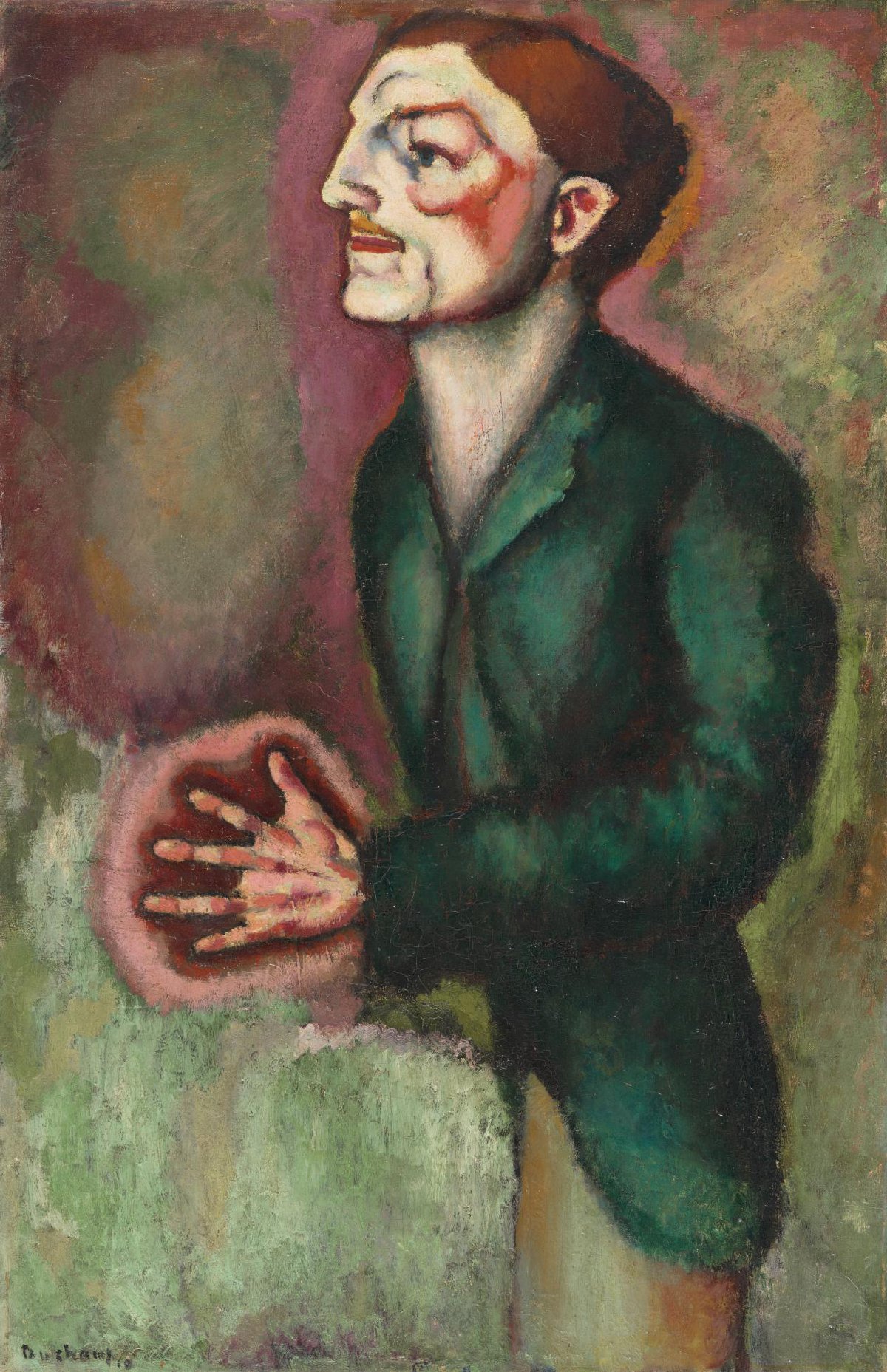

The first radiation-powered X-man?

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

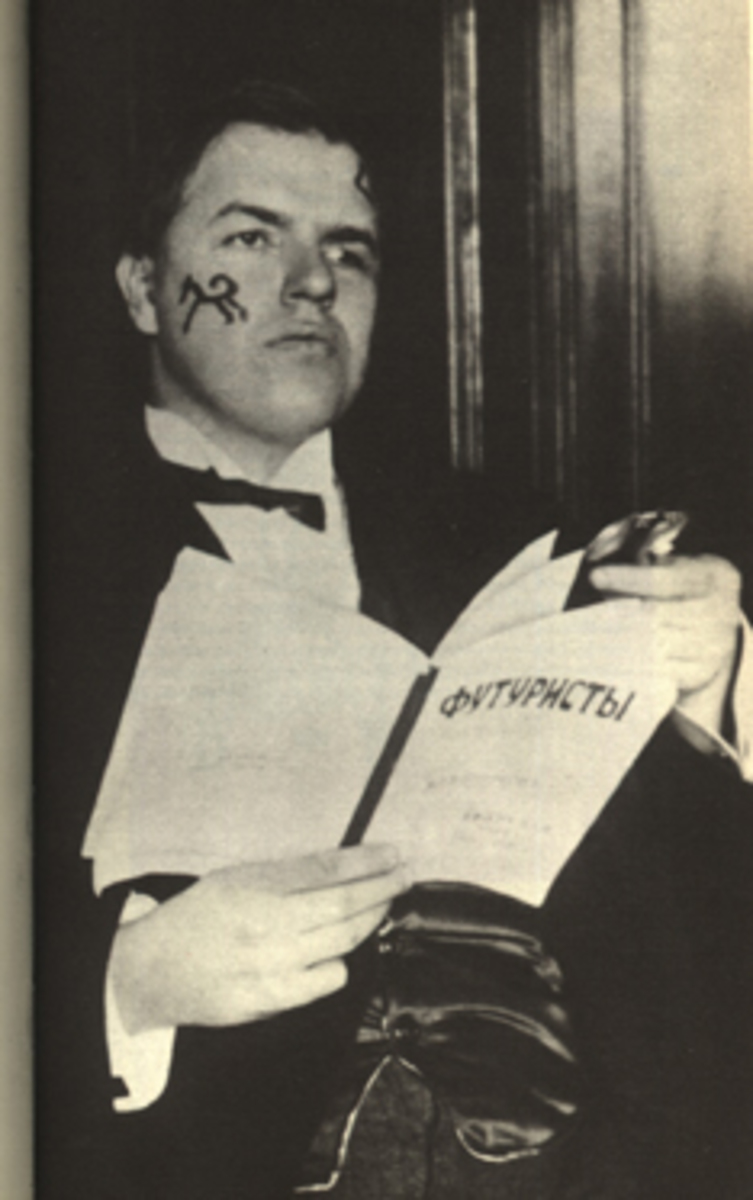

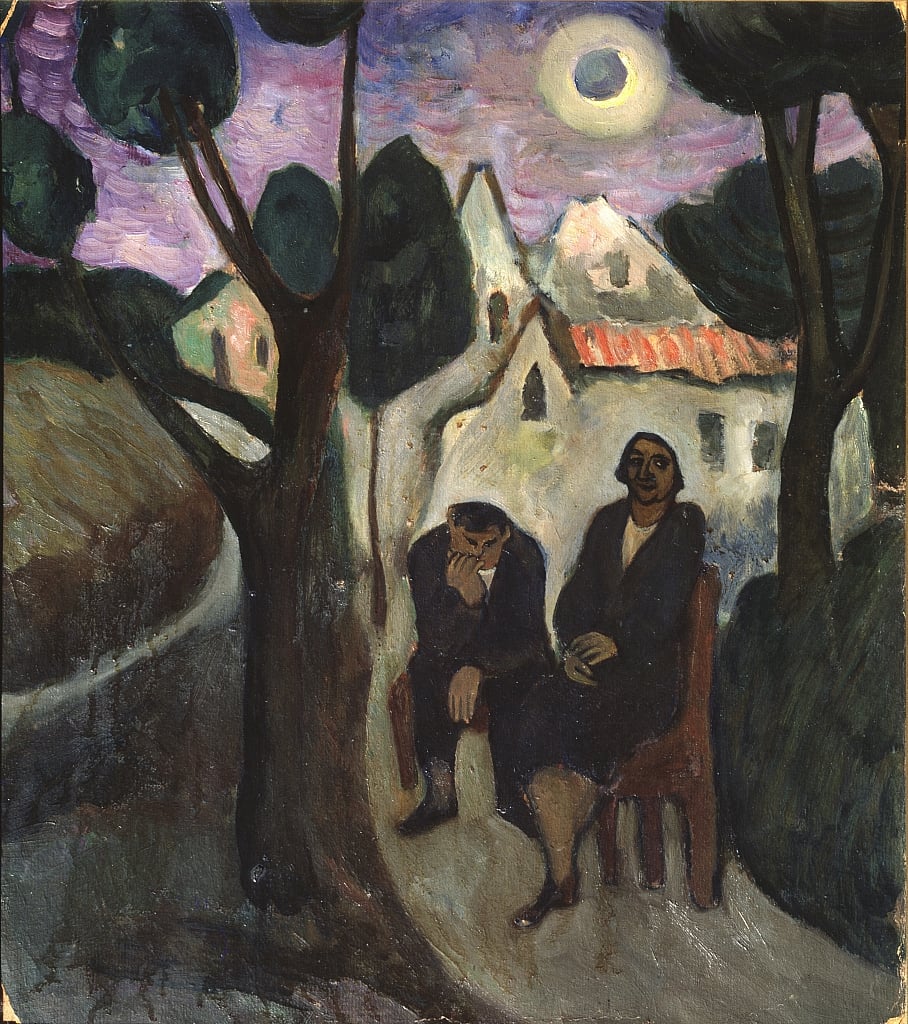

The Futurist literary group Hylaea (also rendered as Gileia) was launched in 1910 by David Burliuk and his brothers. They were soon joined by Vasily Kamensky and Velimir Khlebnikov; Aleksey Kruchenykh and Vladimir Mayakovsky would join in 1911. Initially formed as a modernist literary collective founded on the principles proposed by Marinetti’s “Manifesto of Futurism,” Hylaea and its members would metamorphose into the Cubo-Futurists. These artists and poets would scandalize the Russian public by wearing far-out clothes and painting their faces, and by writing incomprehensible plays — the most notorious being the cubo-futurist opera Victory over the Sun (see 1913).

Kasimir Malevich (who’d do set design for Victory over the Sun) studied cubism and Italian futurism via exhibitions in St Petersburg and Moscow, via Sergei Shchukin’s extraordinary collection of paintings, and via copies of French books and magazines. His work from 1910–12 show his absorption of these modes.

The years 1910 to 1914 represent an important high point for German Expressionism, a moment when many of these artists were producing their strongest, most paradigmatic works. It was also during this period that the term “Expressionism” came into general usage and became synonymous with the German avant-garde.

Futurism begins c. 1910. The Symbolist movement ends c. 1910.

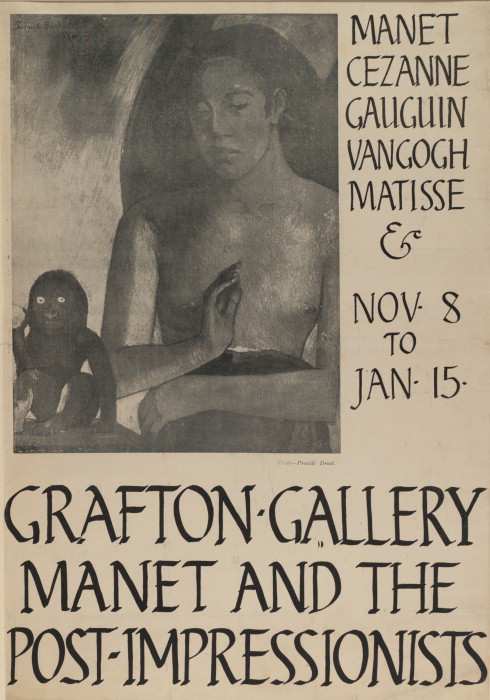

In assembling a controversial exhibition called “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” in 1910, the critic Roger Fry helped awaken a somnambulant England to the exciting new developments in painting that were already electrifying the Continent. The show, which included works by Cézanne, van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso, undermined the popular bourgeois idea of realism and opened the way in England to even more radical developments like Cubism and the Fauves. Prominent among the artists affected by this show were members of Bloomsbury like Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and Virginia Woolf.

Early Cubist Max Weber writes “In The Fourth Dimension from a Plastic Point of View”, for Alfred Stieglitz’s July 1910 issue of Camera Work. In the piece, Weber states: “In plastic art, I believe, there is a fourth dimension which may be described as the consciousness of a great and overwhelming sense of space-magnitude in all directions at one time, and is brought into existence through the three known measurements.”

Claude Bragdon’s The Beautiful Necessity: Seven Essays on Theosophy and Architecture published in 1910.

In 1910, the German physicist Theodor Wulf climbs the Eiffel Tower with an electrometer and discovers the first evidence for the existence of extraterrestrial radiation, now referred to as cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are particles, usually individual protons, that enter our atmosphere at ultra-high energies traveling at very near the speed of light. The term is used to loosely group together extraterrestrial particles from a variety of sources, including those ejected from the sun as well as those that come from elsewhere in our galaxy, and even beyond. The exact origins of cosmic rays is still a matter of some debate, though the accepted hypothesis is that they are ejected from supernovas and propelled to high energies by the accompanying shockwave and magnetic field. Alas for Wulf, his discovery seems to have attracted little attention and was mostly discounted in his time.

Steiner’s An Outline of Esoteric Science (also known as: An Outline of Occult Science) published in 1910.

In 1910, Metzinger published his important Note sur la peinture article depicting the new art movement of Picasso, Braque, and others who have “discarded traditional perspective and granted themselves the liberty of moving around objects.”

Henry P. Manning’s The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained published in 1910.

In 1910, the popular Theosophical writer C.W. Leadbeater’s The Other Side of Death and Clairvoyance (1899) (both of which promote Hinton’s theories about the fourth dimension) would be published in French translation… likely influencing Apollinaire and other French writers and artists. In Clairvoyance Leadbeater deals extensively with x rays. He explains clairvoyant vision as the result of expanding one’s receptivity to new ranges of vibrations:

The experiments with the Röntgen rays give us an example of the startling results which are produced when even a very few of these additional vibrations are brought within human ken, and the transparency to these rays of many substances hitherto considered opaque at once shows us one way at least in which we may explain such elementary clairvoyance as is involved in reading a letter inside a closed box, or describing those present in an adjoining apartment. To learn to see by means of the Röntgen rays in addition to those ordinarily employed would be quite sufficient to perform a feat of magic of this order.

Leadbeater’s text goes on to connect x-ray-like “astral vision” to four-dimensional sight in the same way that the American fourth dimension theorist Claude Bragdon would illustrate the notion in his Primer of Higher Space (The Fourth Dimension) of 1913.

Also appearing in France in 1910 was the criminologist and phrenologist Lombroso’s Hypnotisme et spiritisme (trans. from Italian), which reiterated Zöllner’s theories and accorded scientific respectability to occult notions of the fourth dimension.

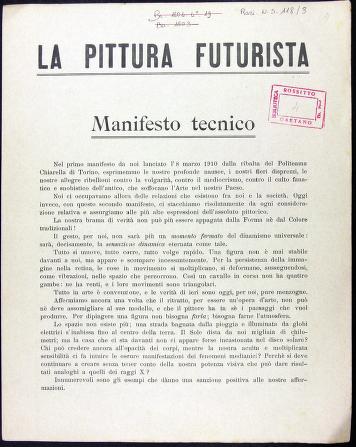

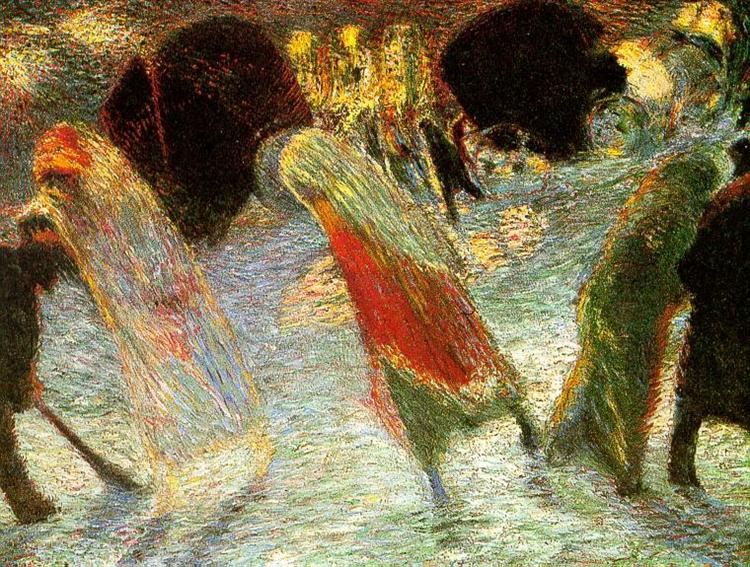

Umberto Boccioni’s 1910 “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting” claims x-rays as a justification for the Futurists’ painting: “Who can still believe in the opacity of bodies, since our sharpened and multiplied sensitiveness has already penetrated the obscure manifestations of the medium? Why should we forget in our creations the doubled power of our sight, capable of giving results analogous to those of the X-rays?” Also: “All things move, all things run. A profile is never motionless before our eyes, but it constantly appears and disappears. On account of the persistency of an image on the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves; their form changes, like rapid vibrations, in their mad career. Thus a running horse has not four legs, but twenty, and their movements are triangular.” Also: “Our bodies penetrate the sofas upon which we sit, and the sofas penetrate our bodies. The motor bus rushes into the houses which it passes, and in their turn the houses throw themselves upon the motor bus and are blended with it.” (See Boccioni’s 1910 painting “The City Rises,” below.)

Likely referring to the first Post-Impressionist show in England, but with the above-mentioned context in mind, Virginia Woolf will later write: “[O]n or about December, 1910, human character changed.”

See: RADIUM AGE: 1910

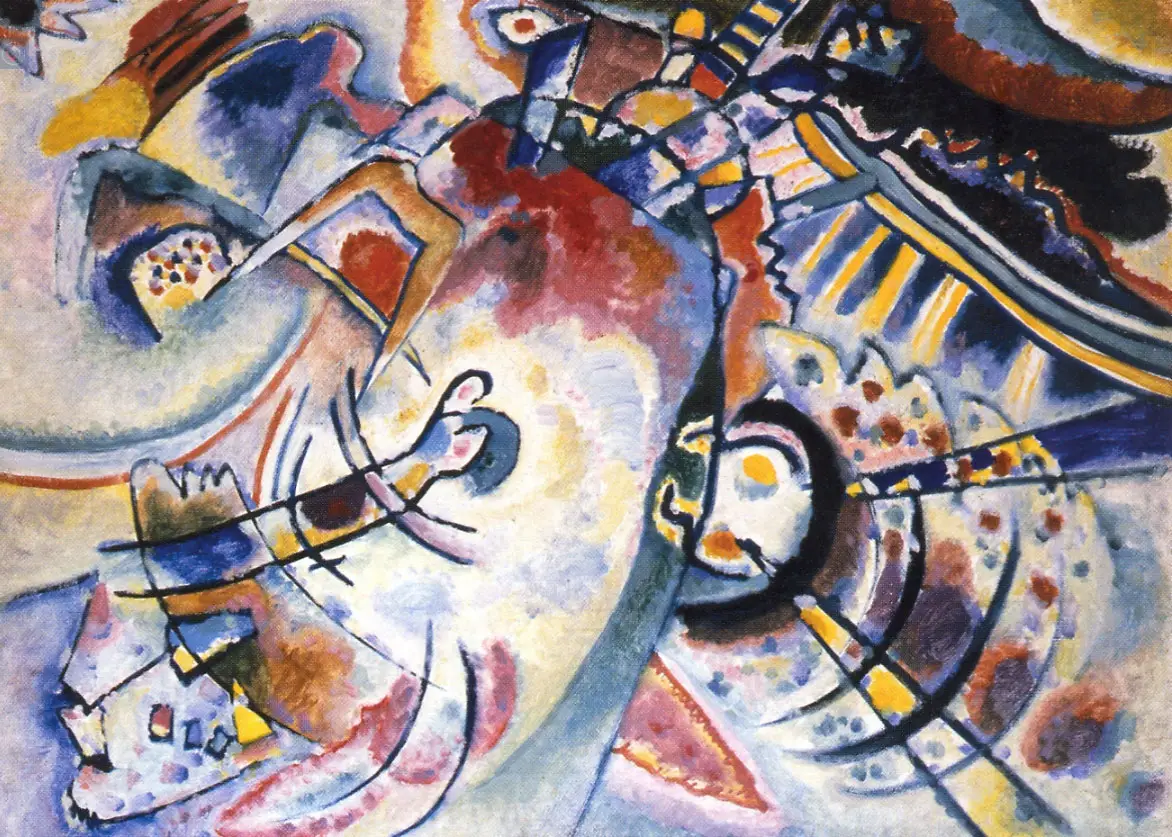

In both Sketch for Composition II and Improvisation 28 (second version) Kandinsky depicts — through highly schematized means — cataclysmic events on one side of the canvas, and the paradise of spiritual salvation on the other.

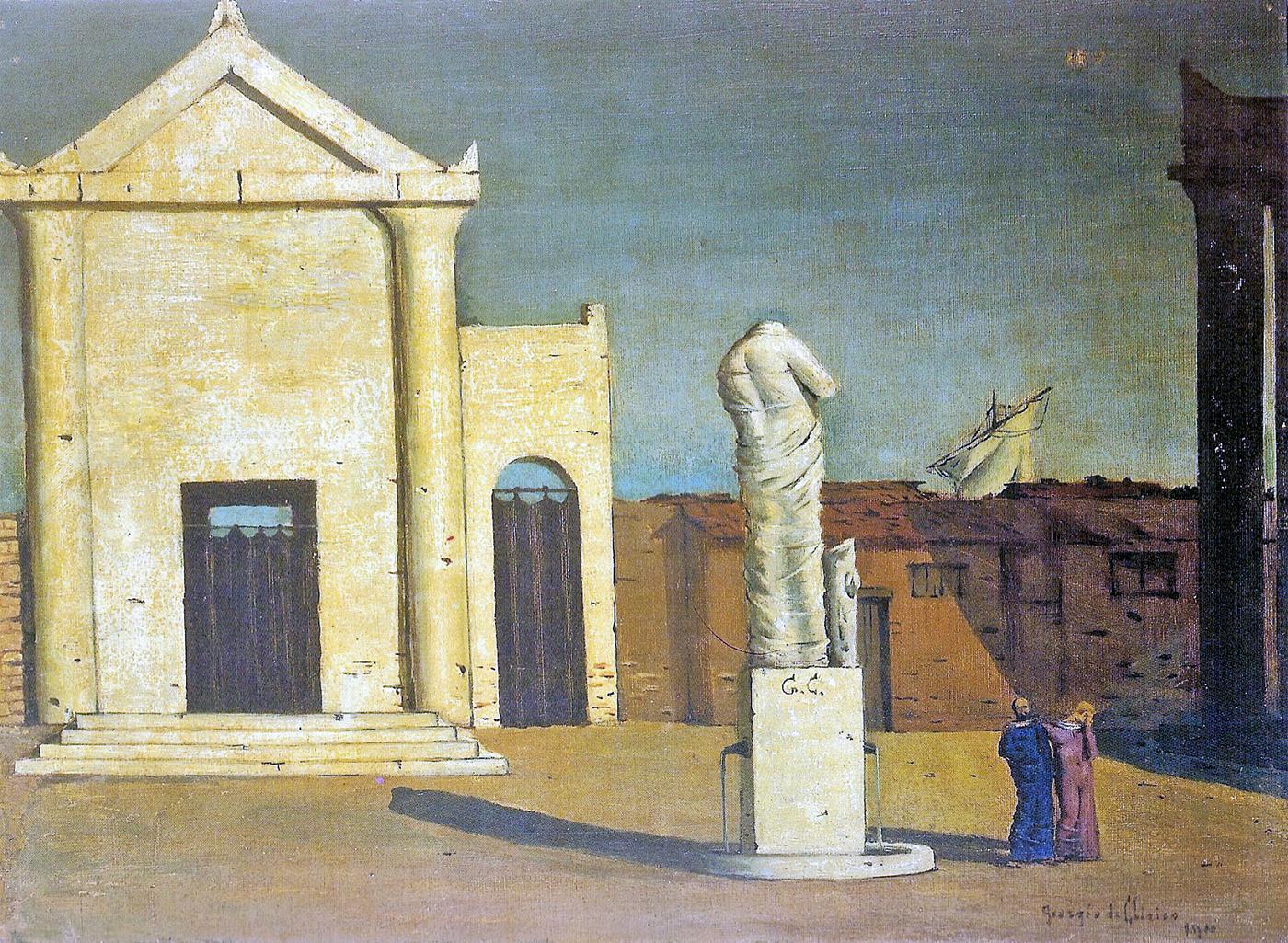

The long, sinister, and illogical shadows cast by unseen objects onto empty city spaces contrast starkly with bright, clear light that is rendered in brooding green tonalities. This is considered the first painting in the Metaphysical mode.

(See more below on Metaphysical Art.)

Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, and Marie Laurencin’s 1911 Salon des Indépendants show would bring the so-called Section d’Or collective to prominence.

Considered the first major work in Léger’s idiosyncratic Cubist style — known as “Tubism.” After seeing the Cézanne retrospective in 1907, Léger’s work became “more focused on geometry and on the representation of a three-dimensional object on a two dimensional support.” (This and the following quotes are from the website Singulart.com.)

“The figures are composed of cylindrical forms: to the left one figure raises its arms, in the centre the figure is seated and to the right, the third figure twists away from the viewer. This composition, combined with the undulating volumes that make up the abstract background creates a sense of mechanical, robotic movement across the landscape.”

“In Nudes in the Forest, Leger demonstrates a concern for construction of three dimensionality on the canvas, as opposed to a simultaneous deconstruction and reconstruction that can be found in the work of Picasso and Braque.” (Singulart.com)

In 1910 he exhibited alongside the Cubist’s at the Salon d’Automne, although he described his own form of Cubism as “Tubism” as he was more preoccupied with cylindrical forms than flat planes. From this point his works became increasingly abstract as he pushed the boundaries of Cubism into pure abstraction.

Sérusier’s series of geometric paintings made c. 1910 convey certain implications of what has been called the “geometric-occult nexus.” Intricate diagrams and charts using sacred geometry to classify nature and life-forms abounded during this period. Sérusier was influenced by Plato’s Timaeus, which offers the pyramid as the origin of all other forms.

“Let it be agreed, then, both according to strict reason and according to probability, that the pyramid is the solid which is the original element and seed of fire; and let us assign the element which was next in the order of generation to air, and the third to water. We must imagine all these to be so small that no single particle of any of the four kinds is seen by us on account of their smallness : but when many of them are collected together their aggregates are seen. And the ratios of their numbers, motions, and other properties, everywhere God, as far as necessity allowed or gave consent, has exactly perfected, and harmonised in due proportion.” — Plato’s Timaeus

Sérusier hoped to restore forgotten rules based on geometry to a religious art; his goal was to depict the fixed and unchangeable rather than quotidian reality. (Plato’s Timaeus claims the pyramid is the origin of all other forms.) Contemplation of these universal forms was supposed to induce in viewers of these paintings a sense of “equilibrium.”

Though realistic elements are present, such as the building, and the space is still rendered through perspective, this painting is considered the artist’s first true futurist work. Men and horses are melted together in a dynamic effort.

The Sacred Heart basilica is the most identifiable symbol of Montmartre. (Picasso also painted it, in 1909.)

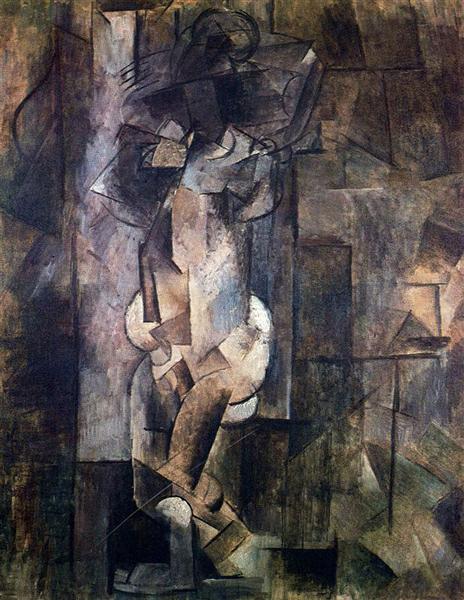

A painting often said to epitomize the dynamic, energetic qualities of Analytic Cubism — an effort to depict three-dimensional objects on a flat canvas without the use of traditional perspective. Perceived forms are broken down, fractured, flattened, then reconstructed in multiple-point perspective within a shallow space — thereby allowing the viewer to see more of the form than would be possible from a single vantage point. Which, by the way, makes me think of 2D renderings of 3D Platonic solids — i.e., schematic diagrams.

En L’An 2000 (In the Year 2000, also loosely translated as France in the 21st Century) is a French image series depicting scientific advances imagined as achieved by the year 2000. At least 78 were produced, by artists including Jean-Marc Côté. They were printed in 1899, 1900, 1901 and 1910, first on paper as cigar box inserts, and later as picture postcards.

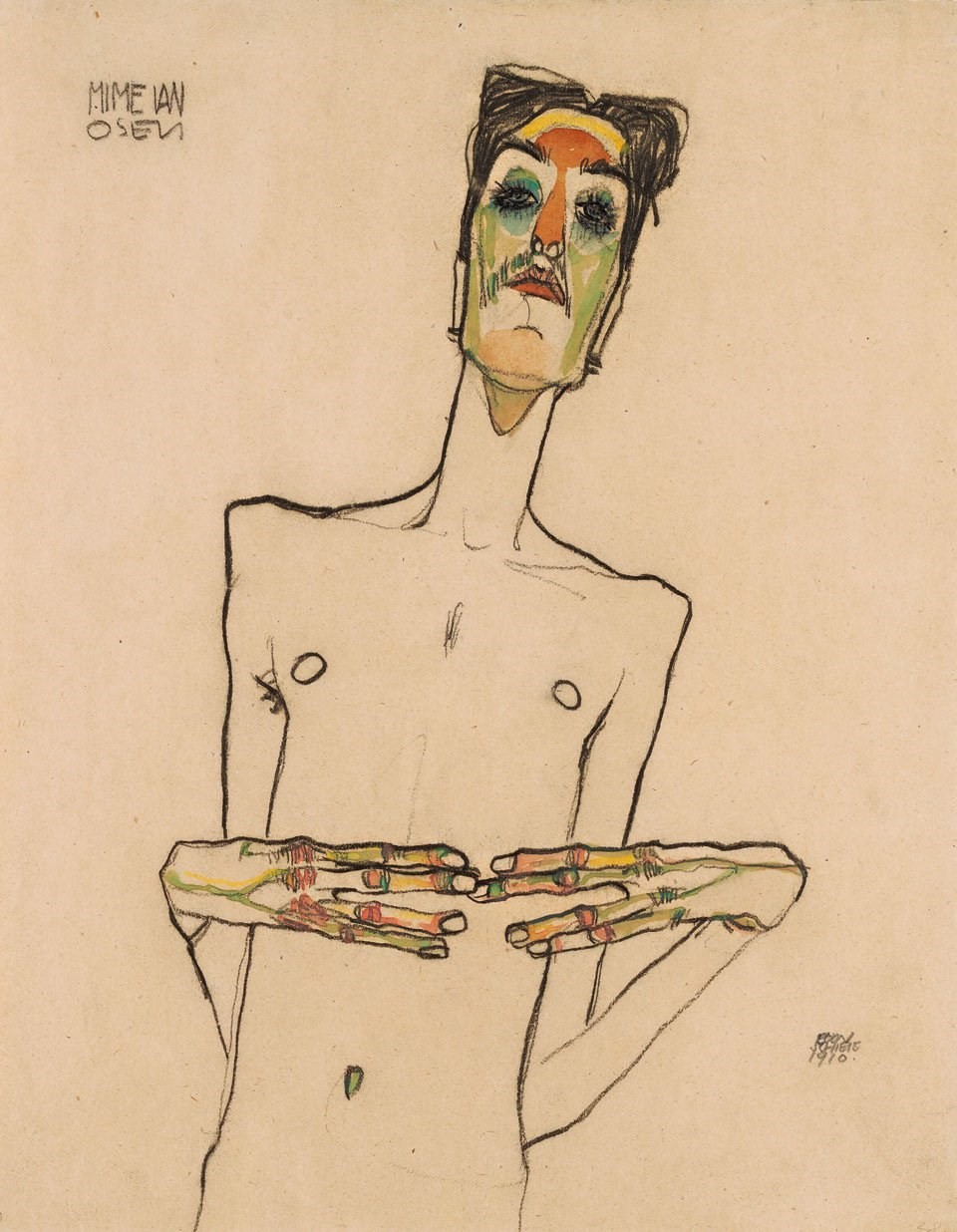

David Bowie would, of course, later be influenced by Schiele. He became acquainted with Schiele’s work when living in Berlin in the 1970s. Bowie’s LP covers from the period are inspired by Schiele’s positioning of limbs and figures — see in particular Schiele’s Self-Portrait as Saint Sebastian (1914) and compare with Bowie’s 1979 Lodger cover.

Exhibited in the Armory Show of 1913.

See below for example of this artwork used as an sf book cover illustration.

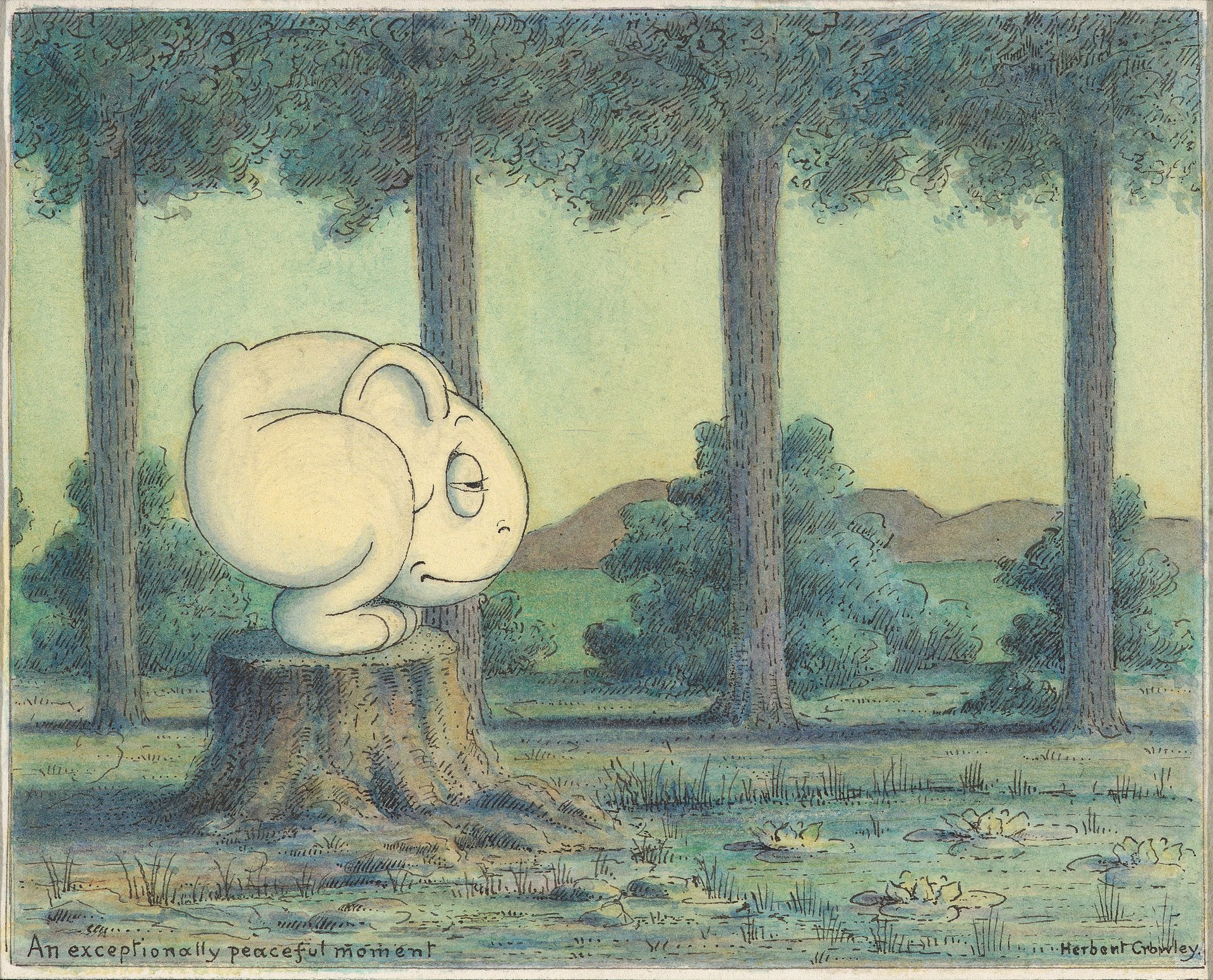

Herbert E. Crowley (1873–1937) was a British artist, set designer, and comic-strip cartoonist. He is the author of The Wigglemuch, a symbolic comic strip published by the New York Herald. It ran for a total of 13 installments from March to June 1910. Crowley’s art work was exhibited in the 1913 Armory Show.

In a 1914 review of another Crowley exhibition, The New York Times remarked, regarding the exhibit’s catalog comparison between Crowley and William Blake, that “what resemblances may exist between the two artists is strongest in the spiritual quality of their attitude toward their art and a kind of personal symbolism not very clear to the uninitiated.”

In 2016, his works (many of which were unpublished) were collected in The Temple of Silence: Forgotten Worlds of Herbert Crowley, a crowdfunded book by Justin Duerr, published in 2019 by Beehive Books

It’s been said of Leaving the Theatre: “One of the most important and representative works of early Futurism, painted in the ‘Divisionist’ style typical of the movement’s initial phase. It was created around a year before Carrà and his colleagues encountered Cubism in the autumn of 1911, and captures the dynamism of modern city life in shimmering dashes of paint that create a vivid sense of animation and flux.”

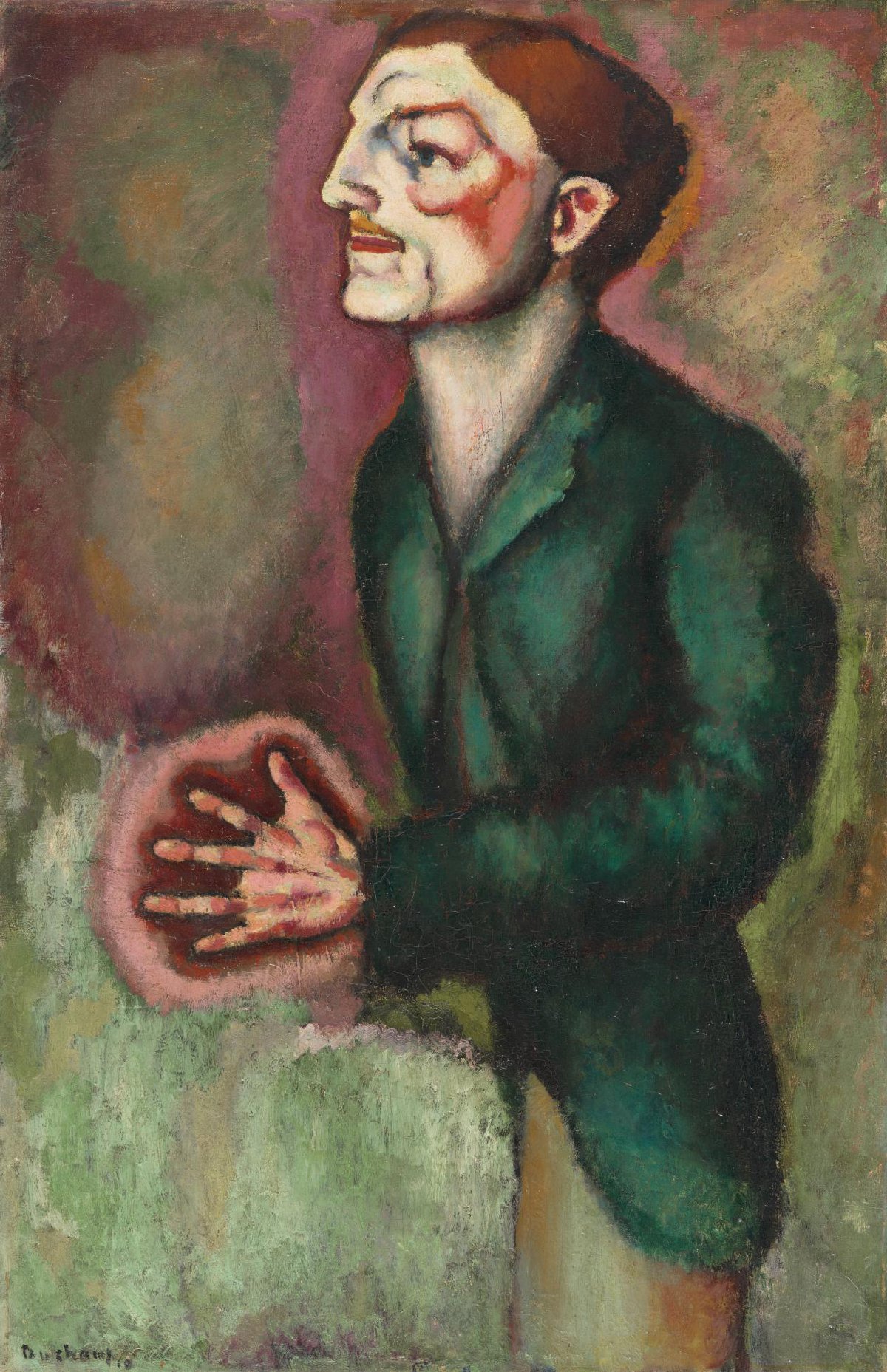

Raymond Dumouchel was a former schoolmate of Marcel Duchamp’s and a student in Radiology, an emerging field at the time (X-rays having been discovered in 1895). Duchamp painted the left hand of Dumouchel surrounded by an aura, suggestive of both the rays he worked with and the man’s healing powers. Is this the first superpowered “X man” ever to appear in modernist art?

By Summer 1910 Picasso’s figures have become a type of skeleton, now consisting of a linear grid, with object and space completely interpenetrating. “With their surfaces activated by monochromatic Neoimpressionist brushstrokes, the paintings of Picasso and Braque from 1910 through early 1912 give physical form to Bergson’s philosophy of continuity and to the popular notion of universal radioactivity propounded by Le Bon, in particular. Matter dematerializes into energy before one’s very eyes.” (Linda Dalrymple Henderson)

In 1910 Picasso and Braque rotate the diagonal lattice of early Cubism so that it becomes an orthogonal grid or narrow, interwoven strips, punctuated by tilted planes. The rectilinearity of a grid seems incompatible (Pepe Karmel points out) with the curves of a human body, and its rigidity antithetical to the idea of motion. Yet bodies and motion would be plotted against such grids — if not necessarily by Picasso and Braque, then by Duchamp, Picabia, Van Doesburg, Bomberg, etc.

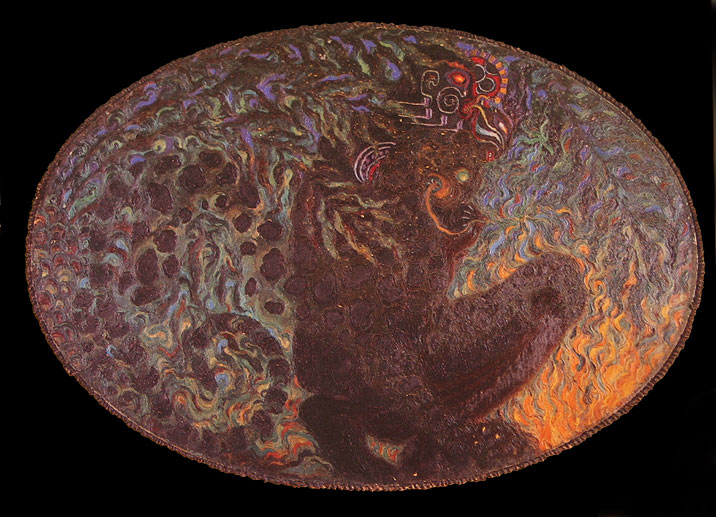

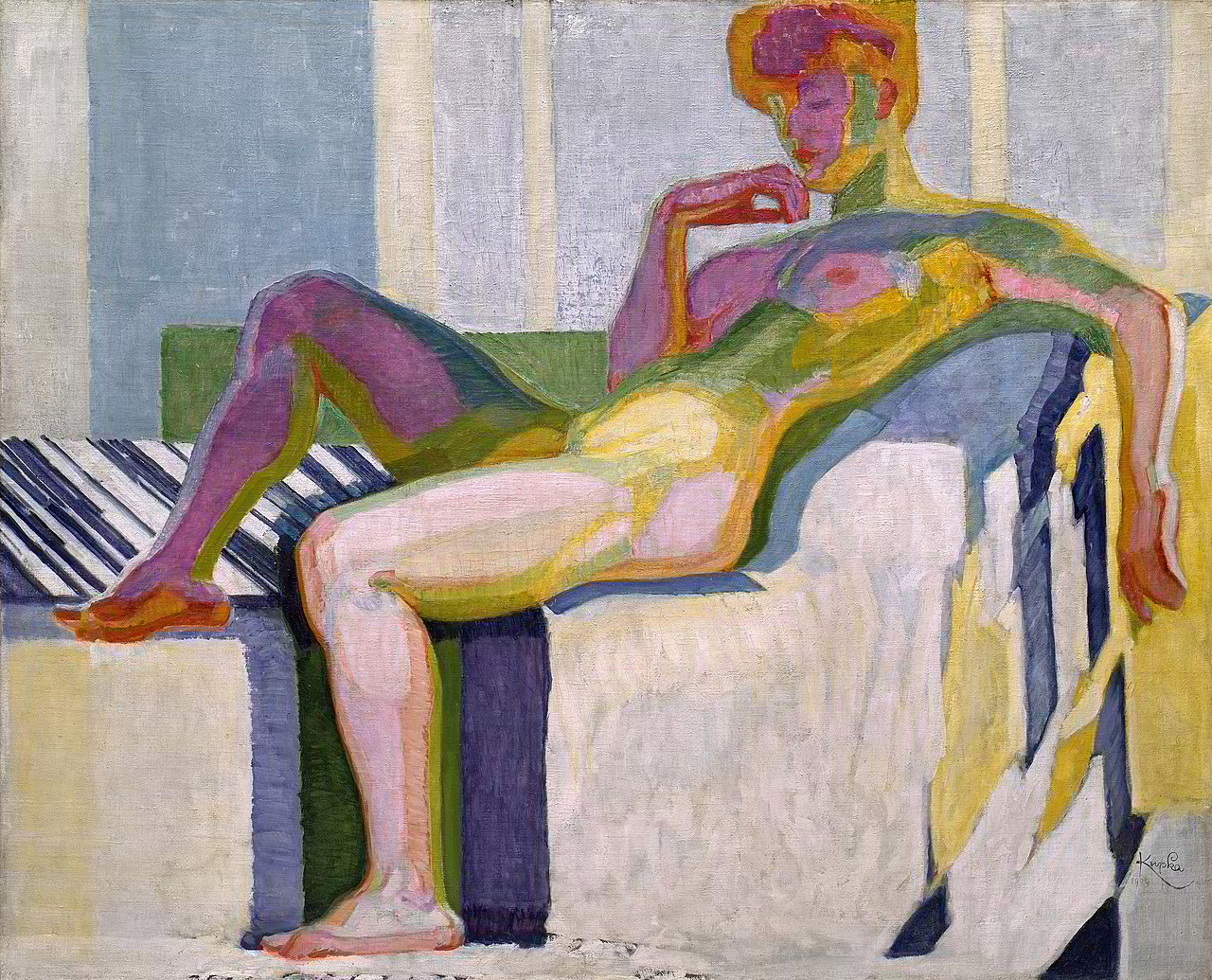

X-ray inspired painting that contrasts external appearance and internal form. Contrasts the sensuality of the surface with the “form in itself” (a Kantian-ish term used by Kupka) as revealed by x rays.

Bridget Alsdorf, at the Guggenheim website:

Theosophy — a synthesis of philosophy, religion, and science — guided Kupka’s holistic approach to art. His paintings draw on a variety of sources, including ancient myths, color theory, and contemporary scientific developments. The invention of radiography at the turn of the century was especially significant for Kupka, whose search for an alternative dimension through a kind of painterly X-ray vision is captured in his monumental Planes by Colors, Large Nude. In this work, Kupka rendered the figure of his wife, Eugénie, in vivid shades of purple, green, yellow, and blue, devising an innovative modeling technique based on color, not line or shade, that sections her body into tonal planes in such a way that her “inner form” is made visible. This unveiling of the unseen is crucial, for Kupka believed that it is only through the senses, through physical experience, that we can reach an extrasensory, metaphysical dimension and thereafter achieve an intuitive understanding of the universal scheme underlying existence.

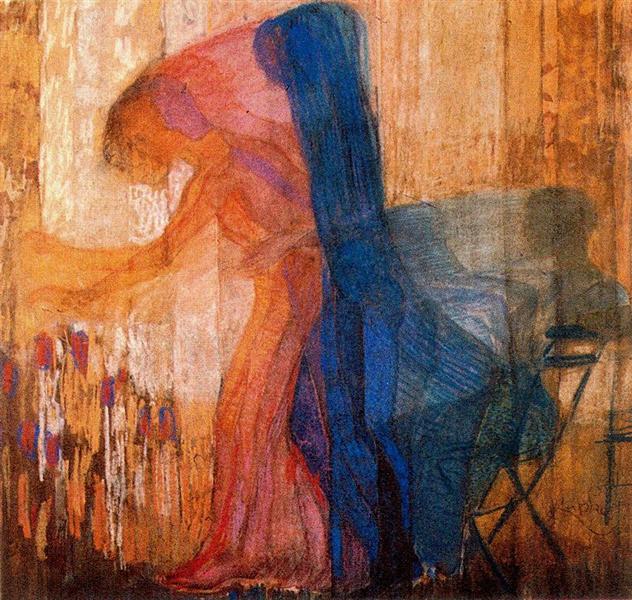

Kupka’s painting uses semi-transparent figures (as in his earlier painting The Dream) to give physical form to motion “and to reveal a dynamic invisible reality.” (Linda Dalrymple Henderson)

During the years 1910–1913, Kandinsky was deeply engaged in “painting the pictures that led him into the realm of abstraction,” and at the same time formulating the theories supporting this effort (Hilton Kramer). Kramer notes that Kandinsky’s occult mysticism was more socially and emotionally engaged than Mondrian’s. Also, Kandinsky’s aesthetic of abstraction had its roots in the disorderly, emotion-charged conventions of Expressionism… his abstractions therefore “abounded in graphic improvisation, coloristic invention, ‘hidden’ images, and a tumult of painterly dynamism….” His abstraction “embraces the fluidity and flux and thus the sensuality of the minds impressions…”

Arthur Dove’s first series of abstractions is in 1910. Like many American abstract painters he also relies on the American tradition of landscape painting.

Artists, like Burliuk, associated with Russian Futurism sought to both question and analyze — what they called “deconstruct” — established principles of art, including a classical attention to realism, balance, and natural subject matter.

See this Google Arts & Culture exploration of the painting. Here, we read that “The composition seems to mix three layers of time. The first is the background, on which time is depicted as emerging and passing, written as if in weightlessness. The second plane is the present time, realistically embodied in a static face. The third plane, transcendental, is the viewer looking at the picture from the future.”

MORE NOTES ON ABSTRACT ART

Around 1910, groups of artists break away from representational art toward abstraction, preferring “symbolic” color to “natural” color, signs to perceived reality, and ideas to direct observation — why? Why head in this direction? Their art reflects a desire to express spiritual, utopian, or metaphysical ideals that cannot be expressed in traditional pictorial terms. Objective and imitative forms cannot communicate from “soul to soul”; subjective and non-imitative forms perhaps can do so.

Hilton Kramer notes that Kandinsky and Mondrian, despite the great differences in the style of their abstractions, were both guided by “the metaphysics of the occult, which in the end emancipated them from the mundanity of the observable world.”

Pepe Karmel’s Abstract Art: A Global History claims that what made the new art “abstract” was not the absence of resemblance — he claims that abstraction is a form of representation, a combination of abstract forms with meanings generated by associations with the real world — but the destruction of the fixed viewpoint. (European art for ages had presented figures and objects as if they were displayed on a stage; every element of a painting was coordinated to imply that the viewer occupied a particular place in front of the imaginary scene.) “The ultimate goal of abstraction was freedom: a new freedom of expression for the artist, a new freedom of intepretation for the viewer.”

NOTES ON SACRED GEOMETRY

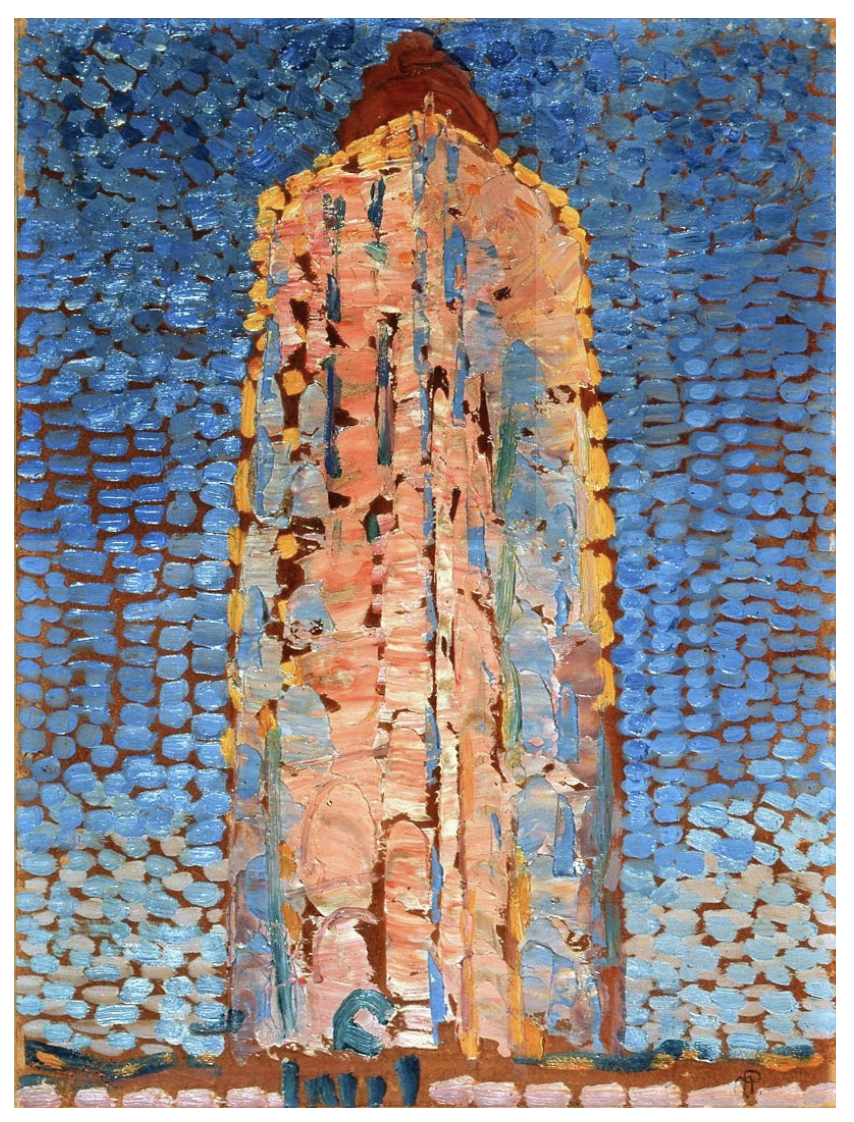

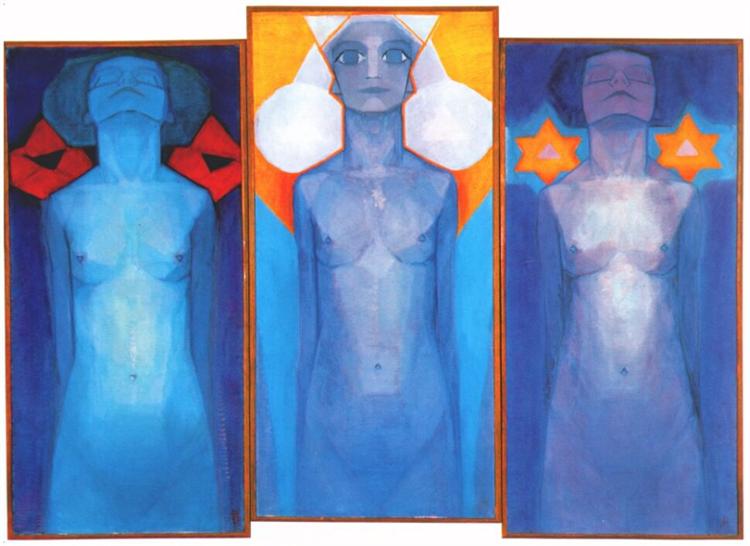

Mondrian’s transition from naturalism to abstraction begins c. 1910. Of the four “founding fathers” of abstract art, he was most consistent and systematic in his use of simple geometric figures. His 1910–1911 painting Evolution (above) uses theosophical hexagrams, circles and triangles. The geometric tendency in his work around 1910–1911, one reads, “adheres to the esoteric interpretation of mathematics that had already by that point been playing an important role in aesthetic thinking among theosophists.” In 1911 Mondrian encountered the Cubist work of Picasso and Braque; their method seemed to him to offer an excellent means of visualizing the essence of things by way of their dematerialization.

Mondrian came to use primary geometrical forms because they are the forms furthest removed from physical reality. Spirit is most easily approached by means of a form which is closer to the Spirit — and least easily by actually physical forms.

His aesthetic of abstraction is derived from the ‘logic’ of Cubism (therefore it’s less emotional and tumultuous than Kandinsky’s abstraction). His mode of abstraction finds its ideal in a pictorial style of straight lines, primary colors. and rectangular structures. Kramer on Mondrian: Everything in his abstraction “seeks fixity and order…” His approach is that of an ascetic “determined to strip nature of its mutable attributes.” He is a diagrammer, a semiotician in the arts.

NOTES ON THE FOURTH DIMENSION

Around 1910, the artistic possibilities of the Fourth Dimension, as well as fin-de-siècle scientific advances around radioactivity, begin to escape the proto-sf space and go mainstream.

The fourth dimension — widely popularized in books like 1910’s The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained (Henry P. Manning), which frequently mentions the late-19th century German astrophysicist and psychical researcher J.C.F. Zöllner’s theories, was often equated with the new “cosmic consciousness” and placed in an artistically and philosophically productive context.

See Tom Gibbons’s essay “Cubism and ‘the Fourth Dimension’ in the Context of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Revival of Occult Idealism.”

NOTES ON METAPHYSICAL ART

Metaphysical art was a style of painting developed by Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. The movement begins in 1910 with de Chirico, whose dreamlike works with sharp contrasts of light and shadow will often have a vaguely threatening, mysterious quality, “painting that which cannot be seen.”

De Chirico is retro, in a sense; he is inspired by the paintings of the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin and the work of German artists such as Max Klinger.

His painting The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon (c. 1910) is considered his first Metaphysical work; it was inspired by what de Chirico called a “revelation.” In 1913, Apollinaire would make the first use of the term “metaphysical” to describe de Chirico’s painting.

“Sometimes the horizon is defined by a wall behind which rises the noise of a disappearing train. The whole nostalgia of the infinite is revealed to us behind the geometrical precision of the square. We experience the most unforgettable movements when certain aspects of the world, whose existence we completely ignore, suddenly confront us with the revelation of mysteries lying all the time within our reach and which we cannot see because we are too short-sighted, and cannot feel because our senses are inadequately developed. Their dead voices speak to us from nearby, but they sound like voices from another planet.” — Giorgio de Chirico

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.