INTO THE GROVE (11)

By:

April 29, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

John Skelton’s A Selection from His Poems, edited by Vivian de Sola Pinto (1952)

Marius Bewley’s Complex Fate: Hawthorne, James and some other American Writers, introduction by F.R. Leavis

Giovanni Verga’s Little Novels of Sicily (1883), translated by D.H. Lawrence (1928, 1953)

Giovanni Verga’s Mastro-Don Gesualdo (1889), translated by D.H. Lawrence (1928, 1954)

Vernon Lee’s The Snake Lady and Other Stories, introduction by Horace Gregory (1954)

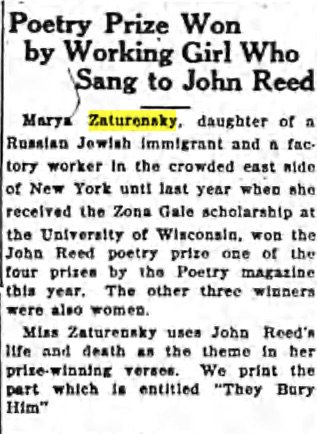

Marya Zaturenska’s Selected Poems (1954)

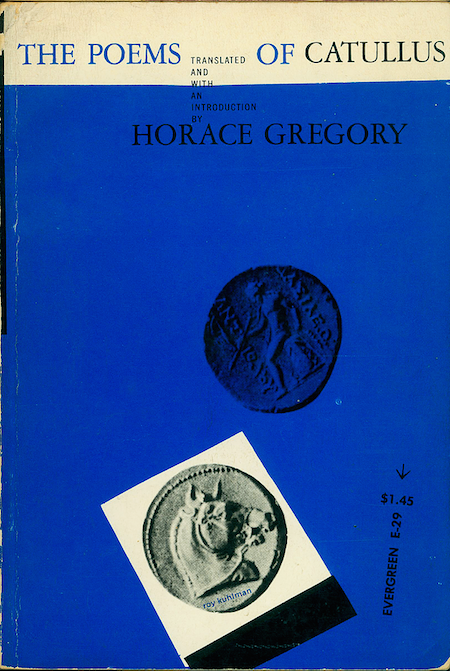

Horace Gregory’s The Poems of Catullus (1931, 1956)

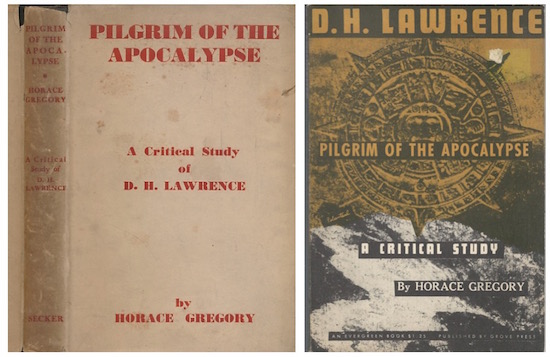

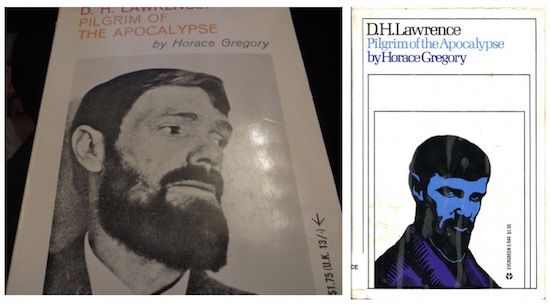

Horace Gregory’s D.H. Lawrence Pilgrim of the Apocalypse: A Critical Study (1933, 1957)

All covers by Roy Kuhlman except where noted

When I began this series, I knew that the May 1959 publication of the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover was a turning point. Impressive as it was, the achievement of Grove Press to that point was largely aesthetic. While Barney Rosset had exceptional taste both in literature and design — imagine Roy Kuhlman’s genius confined to Madison Avenue hell? — relatively little of what he’d published was unique to Grove. Books came from the public domain; the richness of world literature; other publishers’ hardcover lists. It was a great catalog, and it usually looked fantastic, but these are the virtues of the bibliophile, the salesman, the shopkeeper. With Chatterley, Rosset would directly challenge some the most repressive currents of American history.

Rosset had done so once before, as the producer of Leo Hurwitz’s post-World War II anti-racial discrimination documentary, Strange Victory. The picture had opened, barely, in September 1948, but who saw it? And what, practically, did it matter — except to make J. Edgar Hoover’s job easier. Reds and Jews for blacks, oy! President Truman had already issued Executive Order No. 9881, desegregating the U.S. military, that July and while that wasn’t really the picture’s point… Wasn’t that enough?

Our story begins with a brief look back.

In October 1951, the British scholar Vivian del sola Pinto delivered a lecture at the University of Nottingham — subsequently issued as a chapbook — titled D.H. Lawrence: Prophet of the Midlands. The following year Grove Press published John Skeleton poetry collection edited and introduced by Pinto. (See Into the Grove #3.)

In 1954, Grove published British-born Rutgers professor Marius Bewley’s The Complex Fate, with an introduction and — somewhat weirdly — a couple chapters of Leavis’ critical interruption by F.R. Leavis, whose imposing D.H. Lawrence: Novelist Alfred A. Knopf will soon publish. Leavis is a character, both brilliant and maddening and though he isn’t much of a Chatterley man, he doesn’t lack for Lawrencian passion.

Coincident with these associations, Barney Rosset seeks out Lawrence’s widow, Frieda, and informs her of his desire to publish the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover, banned — on the basis of 1870s Post Office obscenity laws — in the United States since 1928. Because this, Lawrence’s third, final and purposefully explicit version of Chatterley was, due to oddities in copyright law, in the public domain, Rosset didn’t need Frieda’s permission but he did want her blessing, which she granted. His plans would take some time to effect however and on August 11, 1956 in Taos, New Mexico, Frieda died before they were realized. Had other publishers offered support for Rosset’s endeavor it might have happened sooner but they didn’t. Not Bennet Cerf’s Random House, which had fought for Ulysses back in 1933; not James Laughlin’s often intrepid New Directions, which had a handsome, Alvin Lustig-designed volume of Lawrence’s poetry in its catalog; no one. Chatterley’s “cunt” and “balls” and “warm hearted fucking” wasn’t a problem they needed, nor necessarily believed in. “Collieries” can be a dirty word too though and so Rosset would go it alone.

In the interim, Rosset would publish Lawrence, in his little-known role as translator of the great Italian writer Giovanni Verga. If these are relatively minor entries in the Lawrence canon, they aren’t unimportant and their value to our understanding of Italian literature in English remains substantial. To make the broadest possible cultural association, anybody who’s enjoyed the Sicilian scenes of The Godfather would likely find Verga engaging too.

By 1954, one of Barney Rosset’s informal editorial advisors was the eminent poet and Horace Gregory. The first two Grove titles reflecting Gregory’s influence were both by women: stories by the remarkable British writer Vernon Lee — born Violet Paget — and poems by Gregory’s wife of three decades, the once much acclaimed, by now increasingly ignored lyric poet Marya Zaturenska. This was favoritism, of course, and glanced at today, when her reputation is largely non-existent, one might guess Rosset was doing Gregory a favor by publishing Zaturenska at all. On closer reading, this is plainly untrue — Gregory and Zaturenska were both brilliant writers — though understanding her place in the Grove Press Chatterley saga will require some background.

She was born in Kiev, Russia, in 1902, and her family’s name was Zaturensky, with a “y.” In 1910, the Zaturenskys emigrated, settling on the heavily Jewish Lower East Side, where it’s presumed they spoke Yiddish. Marya attended public school until the age of fourteen, when to support her family — which following her mother’s death soon after arriving in America, now included a step-mother of whom nothing is known — she went for work in a local textile factory. Gifted in English, the teenager went to night school at the Henry Street Settlement, where her talents were noted and assistance offered; a job at Brentano’s bookstore followed, then, with help from Marya’s earliest mentor, the journalist and poet Jeanne Robert Forster, newspaper work. Though her reportage had no byline, “Marya Zaturensky” did occasionally review poetry for the New York Post, in addition to publishing her own verse the Harriet Monroe’s prestigious Poetry magazine. Among Zaturensky’s earliest published poems are “A Russian Easter” (April 1920), set at the great cathedral in Moscow:

Nataska will be there in a scarlet cloak,

And Irena’s gown will be embroidered in crimson

Sergei will be there, and Igor

Will gave with mystic Slav-eyes at the gold altar

and “Song of a Factory Girl” (September 1921) which begins:

It’s hard to breathe in a tenement hall

So I ran to the little park,

As a lover runs from a crowded ball

To the moonlit park

In 1919, with the support of novelist of Willa Cather, Zaturesnky secured a scholarship to Valparaiso University in Indiana, and the next year, she earned a better one to the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Though her degree would be from the library school, Zaturensky remained devoted to literature, being advised by the eminent poet and translator William Ellery Leonard and serving as co-editor — along with a blazingly bright young Illinoisian named Kenneth Fearing — of the Wisconsin Literary Review. After graduation in 1923, both Zaturensky and Fearing moved to New York City, where they remained friends. A year later, Zaturensky won Poetry magazine’s inaugural John Reed Memorial Prize, for her group of elegies on the death of the beloved revolutionary, journalist and poet; this news was printed in The Daily Worker and elsewhere.

In 1925, Fearing introduced Zaturensky to another Wisconsin literary alum a few years their elder, Horace Gregory. Weeks later, they wed and soon Marya Zaturensky would henceforth publish as Zaturenska, with an “a.”

Many decades later, after both his parents were deceased, their son, Patrick would guess the reason for his mother’s name change was a matter of prosody, that she simply liked the “a” sound better. Perhaps this is so. Given Marya’s difficult upbringing however; the scarcity of information about her family; and her lifelong omission of her published work as Zaturensky, I’d suggest the change was also a symbolic act of patricide. Whatever the truth of the matter, when Zaturenska is born, Zaturensky dies, and the body of work that so impressed the young writer’s contemporaries will henceforth be forsaken.

For Horace Gregory, born in Milwaukee in 1898 into a family of some affluence and artistic interests, the struggles of youth weren’t economic but physical. Having contracted spinal tuberculosis as an infant, Gregory’s health was rarely robust: a slight limp, tremors in his right hand, and a tendency towards dramatic mood swings were burdens he would carry throughout adulthood. Graduating from Wisconsin in 1919, Gregory moved to New York, flunked out of advertising and took other disconsolate work while contributing reviews to various periodicals. After they wed, the Gregorys lived in Brooklyn; in the burgeoning left-wing literary community of Sunnyside, Queens; and the Upper West Side, where they began to raise two children. Together, the couple knew nearly everyone in the fractious left-wing New York literary scene and many others elsewhere. A family allowance from Wisconsin kept the Gregorys afloat when the wages of literature were insufficient.

Gregory’s first book of poems, Chelsea Rooming House published by Covici-Friede, co-owned by the revered Romanian-Jewish émigré editor, Pascal Covici. I must pause here to say that whatever one thinks they know about New York literature — whether it be verse, prose, drama or song — their knowledge is incomplete without the reckoning of Chelsea Rooming House, a series of free verse monologues delivered by persons resident in and around the Chelsea Hotel of much later renown. Predating both the Beats and the “New York School Poets” — few of whom, like Gregory, were actually from the city, which freshness was often an artistic advantage — by two decades, Gregory’s debut remains a fascinating and shockingly underknown portrait of a social and cultural scene that would later become legend. Favorite poem titles: “Longface Mahoney Discusses Heaven”; “Time and Isidore Lefkowitz”; “Hellbabies.”

But Gregory wasn’t just a modernist; he was a classicist too, a tremendous combination, and his next book, also published by Covici-Friede, is the Collected Poems of Catullus. While I can delight in translation talk all day, suffice it to say that Gregory’s Catullus is both excellent and somewhat less than ideal. This is the translator’s lot, however, and with unexpurgated Latin and the English on facing pages, impassioned readers can make their own decisions. Here begins the untitled, wonderfully scabrous poem known as Catullus 16:

Pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo,

Aureli pathice et cinaede Furi,

qui me ex versiculis meis putastis,

quod sunt molliculi, parum pudicumFurius, Aurelius, I’ll work your own perversions

upon you and your persons, since you say my poems

prove that I’m effeminate, deep in homosexual vice

More recently, in a prelude to his masterful historical fiction Under Tiberius (2015), Nick Tosches offers a more literal translation of Pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo: “I will fuck your mouth and I will fuck your ass” and as poetry this too cannot be wrong.

Oddly, though the Grove Press Catullus includes a new and informative essay by Gregory, it eschews without comment most of the original Latin, including Catullus 16. Presumably this was done for practical reasons — to make a smaller, more affordable book — and not for censorious, “moral” ones.

Gregory’s third book, published again by Covici-Friede, was D.H. Lawrence: Pilgrim of the Apocalypse. One of the earliest book-length studies of the author, Gregory’s is an incisive overview of Lawrence’s vast and in nearly all ways contentious achievements. As the critic here is himself an accomplished poet, it’s notable that Gregory offers that while Lawrence’s greatest poetry is in his prose, there is greater imperfect value in Lawrence’s verse than many realize.

The first Grove printing of Piligrim features a striking Francine Felsenthal cover inspired, I’m guessing, by Lawrence’s 1926 Mexico novel, The Plumed Serpent. Subsequent Roy Kuhlman designs feature photographic cover that later becomes pop-art psychedelicized.

To be continued…

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.