INTO THE GROVE (3)

By:

March 5, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

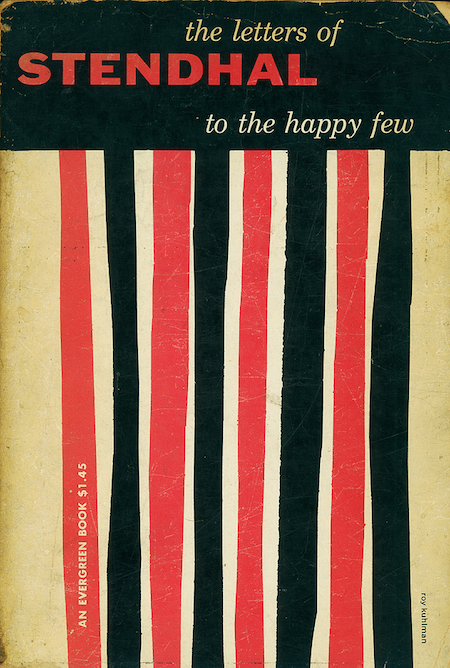

To the Happy Few: Selected Letters of Stendhal, introduction by Emmanuel Boudot-Lamotte, translated by Norman Cameron (1952, Evergreen 1955)

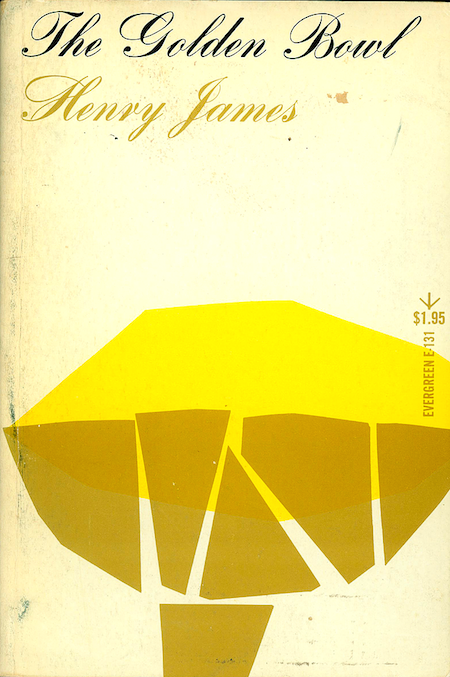

Henry James, The Golden Bowl (1904), introduction by R.P. Blackmur (1952, Evergreen 1959)

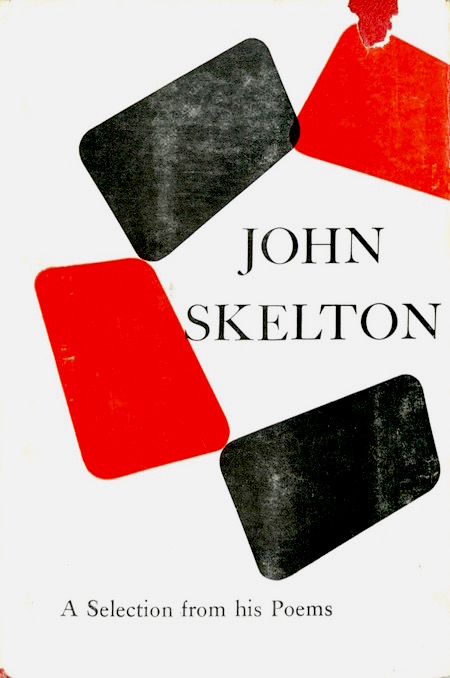

John Skelton, A Selection from His Poems, edited by Vivian de Sola Pinto (1952)

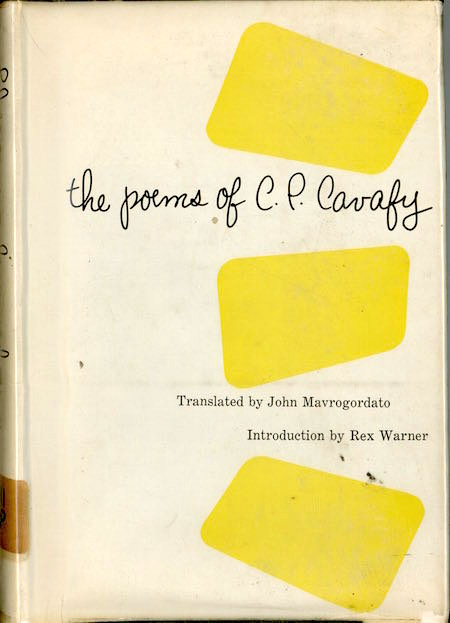

The Poems of C.P. Cavafy, introduction by Rex Warner, translated by John Mavrogordato (1952)

So now in 1952, Barney Rosset, twenty-nine going on thirty, owned his own book company. He moved its business address to 22 W. 9th Street — still in the Village — and set about the task of publishing in a variety of ways. He’d continue to mine the public domain but he also began buying the rights to already published British hardcovers and rebinding them with new covers. Some of these would later become quality paperbacks on the Evergreen imprint while others, for reasons unknown, wouldn’t. Though it’s unwise to over interpret the young Grove Press catalog, its contents are still enlightening. Rosset’s interests were broad and eccentric, and he would have been a terrific publisher even if he weren’t also a troublemaker which, happily for American letters, he was.

If Henri Beyle (1783-1842) — alias Stendhal — isn’t one’s idea of a fun French writer, there are reasons the jovial-minded belle-lettrist might reconsider. There are the great novels, of course, but there’s also Stendhal himself, a man of many guises. His Life of Rossini (1824), a madcap critical biography of the renowned Italian opera composer nine years younger than the author is a literary performance worthy of its subject’s most hilarious, sublime works, and expeditiously slapdash works. Then there’s The Happy Few, a gathering of letters from March 1800 to March 21, 1842 — just two days before Stendhal croaked. Here are glimpses of all the Stendhals, including the satirical food writer. To the Baron de Mareste, written from Trieste, 17th of January 1831:

“… My whole life is reflected in my dinner: my high rank demands that I dine alone — first tedium. Second tedium, my dinner is of seven courses: an enormous capon — impossible to carve with an excellent English knife, which costs less here than in London; a superb sole, which they have forgotten how to cook — a local custom; a woodcock killed yesterday — they would think it rotten if it were kept waiting two days. My rice soup is defiled by seven or eight sausages full of garlic, which they cook with the rice, etc. How am I to protest?”

As neither the John Skelton nor the C.P. Cavafy titles made it to paperback, they’re relatively little known. Both books are notable, however. Design-wise, while Grove’s dustjackets are uncredited, circumstantial evidence points to Roy Kuhlman: they are far more like his known work than unlike it. As for the writers, non-specialists in Tudor-period English poetry might not pursue Skelton (1463-1529) unbidden but for anyone with an interest in vigorous, sometimes roughhouse satire and the potential of poetic forms as social protest, that would be a loss. While Skelton’s inclusion in the Grove catalog reflects the press’s antiquarian founding, Skelton’s dark humor and restlessness makes him a familiar contemporary figure as well; the introduction by the eminent British poet and scholar Vivian de sola Pinto (1895-1969) explains it well. That Pinto was also one of the era’s leading D.H. Lawrence advocates prefigures the day, not too far off, when the author of Lady Chatterly’s Lover would make Grove Press infamous.

The Greek-Egyptian poet Constantine P. Cavafy (1863-1933) is today recognized as a major figure of 20th century world literature but this was hardly the case in 1951. First published by the Hogarth Press of London that year, The Poems of C.P. Cavafy was the first complete Cavafy in English. E.M. Forster called it “the book of the year” and if, after many subsequent translations, contemporary readers will question these rather literal renditions, that scarcely matters. Cavafy was a swart and subtle genius; of course there are many ways to re-present him. As Rex Warner — author of the 1941 English dystopia novel The Aerodrome and a himself a formidable translator of Greek and Latin — avers:

The main sources of his inspiration are the by ways of ancient history and to what most people would appear as scandalous love affairs…. His world is the world most English schoolmasters would describe as decadent. It is a world without any of the obvious epic, lyric or tragic grandeurs. Yet it is a world that existed and exists. It can be examined minutely and dispassionately. Cavafy brings a peculiar point of view together with a singular integrity.

Sound like anyone we know, perhaps William S. Burroughs? Barney Rosset had the eye, even in 1952. As for Cavafy, who was gay, and whose verse doesn’t disguise it, in a largely positive New York Times review, critic John Brooks offered “That his passion to live as a Hellenistic pagan may have stemmed from the perversity of his nature does not make that passion less the genuine.” Hmmmm…

Henry James’ late-period novel The Golden Bowl (1904), urged upon Rosset by his soon-to-be-ex-wife Joan Mitchell, is also the first public nod to one of Grove’s greatest inspirations as a publisher, James Laughlin’s New Directions, which had reprinted four James books in recent years. It’s easy to become impatient with James and, as a fervent Dreiserian, I’ve done so myself. But I was wrong. For an incisive overview of the entire Jamesian project, see Ezra Pound’s James tribute, originally published in August 1918’s Little Review and later collected in Pound’s Literary Essays. For a greater understanding of The Golden Bowl’s method, the indefatigable Jenny Davidson in Reading Style: A Life in Sentences, is the explicator of choice. For the final, brief as possible word, honor goes to Ford Maddox Hueffer, a friend and admirer of both Dreiser and the subject of Henry James: A Critical Study (1916):

Looking upon the immense range of the books written by this author, upon the immensity of the scrupulous labours, upon the fineness of the mind, the nobility of the character, the highness of the hope, the greatness of the quest, the felicity of the genius and the truth that is at once beauty and more than beauty, that such immortality as mankind has to bestow (most of them haven’t any souls!), whether of the talking hooter, or the silent pages, will rest upon the author of Daisy Miller. It will rest also with the author of The Golden Bowl.

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.