Bowieology (1)

By:

January 8, 2015

Bowie: Midcentury Postmodern

In 2014 David Bowie marked his 50th year as a mass-media creator. It seemed a good point to survey what we’ve learned, though surely not to sum up, since he’s too fast to take that test. Beginning today and for the next six, Adam McGovern catches up to Bowie, for now. Portions of this essay appeared in Contemporary Authors in 2001.

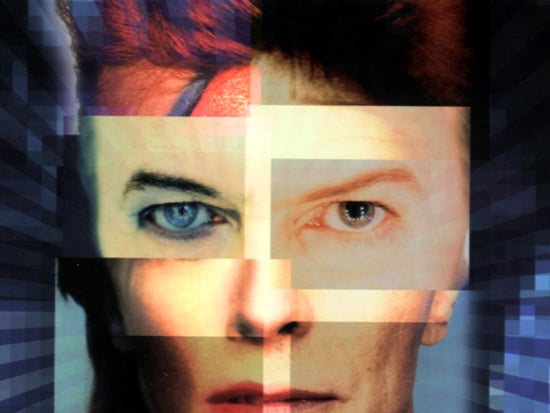

David Bowie is considered one of pop culture’s most prophetic and unusual talents. For five decades he has combined ideas from the social fringe and the artistic avant-garde with the visceral appeal of popular music and multimedia spectacle, to achieve cult stature and eventually superstardom. His techniques have included a blur between high and low culture in his melding of experimental concepts with vernacular idioms; a synthesis of elements from seemingly incompatible styles and historical periods; a malleable conception of the self which has led to a succession of sharply divergent styles delivered by a repertoire of theatrical personae; compositional strategies of chance and intuition derived from the Surrealists, Dadas and Beats and figures such as John Cage and Brian Eno; and wide-ranging appropriation of pre-existing works as a stimulus to his own creativity.

Though known as a stylistic chameleon, Bowie has actually remained remarkably consistent as a kind of commentator on pop culture. Ever reflecting the current moment and seldom repeating the same sound, Bowie doesn’t make albums in diverse styles so much as about them — though his pastiches of them are so convincing that he often ends up being remembered as their originator (particularly with the glam album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, which was in fact produced midway through that style’s first vogue).

Also defining Bowie’s career has been a Warholian disregard for the boundary between art and commerce. Throughout the 1970s, with challenging material that earned him celebrity and sales, Bowie straddled the line. A 1980s detour into mainstream fare made many feel he’d fallen over the line into sheer commercialism. But by the end of the 1990s, with a small industry of financial ventures and online services based on his back catalogue and a restored reputation for his newer work, he once more bestrode the line like a celebrity colossus. In the diffuse culture and do-it-yourself commercial landscape of the 2010s the line seems dissolved, and he crosses it with the fluidity he always seems to have claimed for himself and his following.

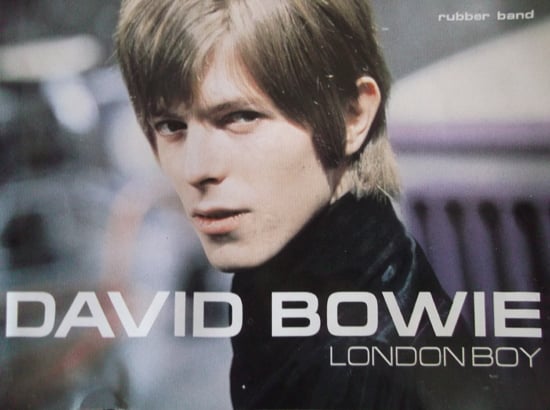

David Robert Jones was born in 1947 amidst middle-class London surroundings which gave little indication or encouragement of the advances he would later make. His high-school education set him toward a vocation in commercial art. But he was also introduced to the literary and musical subcultures of Beat Generation London by his older half-brother Terry, and while still in school David embarked on an itinerant music career (eventually changing his name to Bowie to avoid confusion with Monkees lead singer Davy Jones). Not long after Terry had sparked Bowie’s choice of profession, Bowie saw him institutionalized for the mental illness common in their family. The event haunted Bowie, and was a likely influence on his career-long exploration of altered states of personality and perception.

In keeping with the turbulent self-examination of the Beat and Hippie eras, in his youth and early career Bowie dabbled in diverse artforms and influences which provided a wealth of perspectives for his mature phase, though none of them lasted very long at the time. He came close to taking his vows as a Buddhist monk, and seriously studied mime, at one point actually opening for rock band Tyrannosaurus Rex in that capacity, with a wordless one-man play about China’s invasion of Tibet. He worked as an advertising illustrator and ran a community arts center; appeared in an ice cream commercial and an independent film; and experimented with both straight and gay lifestyles. He marketed himself as an R&B saxophonist, a mod rocker, and a music-hall-inspired mainstream entertainer, first in a string of undistinguished bands and then as a solo act. He would also incarnate as a hippie folksinger and a principal in a psychedelic performance troupe (Feathers) before emerging as an innovative and controversial mass-media personality, in what must have seemed an overnight ascent to the many who hadn’t been watching closely until then.

Up to 1969 about all Bowie had to show for this creative turmoil was a relative handful of mildly ambitious if often derivative singles, and an obscure album of musical-comedy-inspired originals. (Bowie did conceive and star in arguably the first long-form music video ever made, Love You Till Tuesday, but an uncomprehending market kept it without an outlet, and it remained unreleased for decades.)

Bowie first truly put himself on the musical map with the 1969 single “Space Oddity.” A poignant character sketch about a golden-boy astronaut who turns his back on fame, duty and possibly sanity by intentionally disappearing on a historic space-flight, the song signaled Bowie’s arrival as a pithy storyteller. Its drop-out ethic and cautionary spin on mainstream society’s celebration of the space program resonated with both hippie hopes of transcendence and machine-age moods of disillusionment. At the same time, it concisely introduced themes of alienation and futurism which would define Bowie’s career from that moment forward.

The song remained one of his signatures, and was chosen as theme music for the BBC’s coverage of the first Apollo moonwalk, in a classic case of cross-generational misinterpretation. But Bowie’s next two albums would find him struggling to coalesce a distinct identity musically, even as they advanced his voice as a lyricist. 1969’s Man of Words/Man of Music (later known as Space Oddity) alternated between solo acoustic-guitar balladry, folk-rock, and the kind of orchestrated pop for which his previous manager had groomed him; 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World was lumbering heavy metal with lounge and synth-rock leanings. Bowie was maturing faster lyrically, with themes steeped in European folklore, Nietzschean meditations on the tenuousness of godhood, Lovecraftian demonology, Ayn Rand-esque forebodings of social control, and a general interest in science fiction as the modern mythology of a teetering technological empire. The two albums failed to connect with the listening public, ending up being most notable for The Man Who Sold the World’s sleeve, which depicted an ethereal Bowie with long hair and a long dress, a then-transgressive gesture judged unsuitable for release in America until two decades later.

Tomorrow in Part 2: The Passion of Ziggy

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: Theater Reviews: The Honeycomb Trilogy, Love Und Greed, Nord Hausen Fly Robot, The Oracle | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Full Fathom Five,” an analysis of a panel from Jack Kirby’s New Gods | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The 10-part review series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam McGovern’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE