Whaling Songs

By:

November 30, 2011

Imagine, if you will, a Venn Diagram composed of the following sets: Coders. Musicians. Marine Biologists. Paul Winter. Leonard Nimoy. Your high school English teacher. And Ishmael.

The sole resident of the intersecting set would be, of course, a whale.

Or perhaps the whale’s trace, in the form of a song.

[Screenshot, Whale.fm]

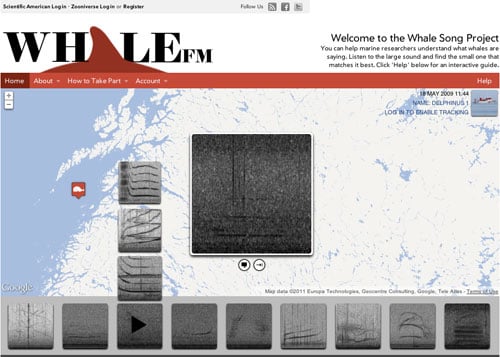

In a mellifluous blend of technology, art, and nature, Whale.fm, a project of Scientific American and Zooniverse, invites the general public to help track and analyze whale songs, gathered from numerous whales around the world. Using embedded recordings, paired with greyscale spectrograms as background/timelines, users can play a whale song, then click through grouped, similar recordings to decide which one best matches.

The songs vary widely, from fairy-like cries, to deep bellows, to almost-mechanical clicks and whistles. We still don’t know what they are saying. But using field recordings, we can compile their first dialect dictionaries. And the spectrograms are striking, a translation of noise and data into a unique, greyscale images, signing the sounds with a visual data flourish.

The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home.

— Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild

Like other citizen scientist endeavors profiled on HiLobrow, such as SETI@Home, Weather@Home, and Project NOAH, Whale.fm harnesses the power and reach of the internet to source data to the crowd. And it’s no mere publicity stunt or pop-tech bubble: there are simply too many notes, and not enough marine scientists to listen. Human ears, not digital data, are needed for the relevant arguments from analogy.

[The Hunt for Red October, dir. John McTiernan, 1990; with Courtney B. Vance as Seaman Jones]

In a process that gestures towards the origin of the term, people are invited to turn back into computers. You are a node in a very large analogue array, processing the sonic data in parallel with your fellow global citizens. If computers enable us to become more like them, a process that is often as limiting as it is cynical, then surely projects like this are features, to counterbalance the manifold bugs.

[Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, dir. Leonard Nimoy, 1986]

And since so much of our time is spent using, depleting, corraling, over-sentimentalizing, killing, or otherwise seriously annoying the other residents of the animal planet, it’s nice that, for once, we’re listening.

[Leonard Nimoy reads Moby Dick, from Whales Alive!, by Paul Winter]